Adoption Metaphors Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Varick Family

THE VARICK FAMILY BY REV, B, F, WHEELER, D, D, With Many Family Portraits, JAMES YA RICK x'Ot:.SDER OF THE A. ~- E. ZIO.S CHT:RCH DEDICATION. TO THE VETERAN FOLLOWERS, MINISTERIAL AND LAY, OF JAMES VARICK, WHO HAVE TOILED UNFLAGINGL Y TO MAKE THE AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL ZION CHURCH THE PROUD HERITAGE OF OVER HALF A MILLION MEMBERS, AND TO THE YOUNG SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF THE CHURCH UPON WHOM THE FUTURE CARE AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE CHURCH MUST SOON DEVOLVE, THIS LITTLE VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE I have put myself to great pains to gather facts for this little book. I have made many trips to New York and Philadelphia looking up data. I have visited Camden, N. J ., and Rossville, Staten Island, for the same purpose. I have gone over the grounds in the lower part of New York which were the scenes of Varick's endeavors. I have been at great pains to study the features and intel lectual calibre of the Varick family, that our church might know something about the family of the man whose name means so much to our Zion Method ism. I have undertaken the work too, not because I felt that I could do it so well, but because I felt I was in position, living near New York city, to do it with less trouble than persons living far away from that city. Then I felt that if it were not at tempted soon, the last link connecting the present generation with primitive Zion Methodism would be broken. -

On Absalom and Freedom February 17, 2019: the Sixth Sunday After the Epiphany the Rev. Emily Williams Guffey, Christ Church Detroit Luke 6:17-26

On Absalom and Freedom February 17, 2019: The Sixth Sunday after the Epiphany The Rev. Emily Williams Guffey, Christ Church Detroit Luke 6:17-26 Yesterday I was at the Cathedral along with several of you for the Feast of Blessed Absalom Jones, who was the first black person to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. Absalom Jones had been born into slavery; he was separated from his family at a very young age, when his master sold his mother and all of his siblings, and took only Absalom along with him to a new city--to Philadelphia--where Absalom worked in the master’s store as a slave. The master did allow Absalom to go to a night school there in Philadelphia for enslaved people, and there Absalom learned to read; he learned math; he learned how to save what he could along the way. He married a woman named Mary and, saving his resources, was able to purchase her freedom. He soon saved enough to purchase his own freedom as well, although his master did not permit it. It would be years until his master finally allowed Absalom to purchase his own freedom. And when he did, Absalom continued to work in the master’s store, receiving daily wages. It was also during this time that Absalom came to attend St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Since Methodism had grown as a form of Anglicanism back in England, this was a time before the Methodist Church had come into its own denomination distinct from the Episcopal Church. -

LEADERSHIP of the AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL ZION CHURCH in DIFFICULT TIMES Submitted by Cynthia En

TELLING A NEGLECTED STORY: LEADERSHIP OF THE AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL ZION CHURCH IN DIFFICULT TIMES Submitted by Cynthia Enid Willis Stewart, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Theology, January 2011. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature.......Cynthia Stewart........................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have completed this labor without the help of Ian Markham whose insightful and thoughtful comments have shaped this thesis. His tireless encouragement and ongoing support over many years despite a busy schedule brought this work to fruition. To Bishop Nathaniel Jarrett of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, my heartfelt thanks for his superior editorial assistance. I thank my husband, Ronald, for his unwavering support. 2 ABSTRACT The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church connection is a major, historic Black Christian denomination which has long been ignored as a subject of serious academic reflection, especially of an historic nature. This was partly due to the lack of denominational archives, and the sense that historical inventory and archival storage could be a financial drain to the AME Zion Church such it could not maintain its own archives and indeed, retaining official records was kept at a far from super or archival level. -

The Black Church “ Lost-Strayed-Or Stolen ” in the Area of Religion Seemed That the Churches Institution of Slavery

THE BETTER WE KNOW US • • by Albert A. Campbell fflGH POINT - Mrs. Letitia B. began viewing life from i different Feeling that she still had not developed well-placed advice, she chose the I.R.S. Johnson, wife, mother and career perspective. She quickly found that first to her full potential, “ Tish” entered During the 1973 Summer, Mrs. woman. A rare combination among of all, there were no jobs for the North Carolina A&T State University in Johnson accepted an opportunity from today’s demands of specializations. untrained, especially for blacks, and that 1970 to study accounting. While a the I.R.S. and attended Basic Revenue From high school drop-out to GS-9...all simply sitting at home was just not full-time student, she also maintained her Agents Training in Atlanta, Georgia. because of attitude! Mrs. Johnson is a enough. By September, 1963, she had role of wife and mother as well as a That exposure, along with instructional living Cinderella testimony. decided to return to high school and get part-time job. In 1974 she graduated advice, made her more aware of the A product of “ The Projects” (Daniel her diploma - which she received in June summa cum laude and No. 1 in the School better opportunities with the I.R.S. She Brooks) in High Point, Letitia attended of 1964. of Business & Finance. She also found had already worked in a Cooperative the now defunct Leonard Street Her first employment was in a factory time for the Alobeaem Society, Educational Program as a Revenue Agent Elementary School before entering the working in a dull, dead-end job that had Accounting Club, and two honor Intern during her senior year at A&T. -

The Emergence of Pentecostalism In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository THE EMERGENCE OF PENTECOSTALISM IN OKLAHOMA: 1909-1930 By MICHAEL SEAMAN Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2018 THE EMERGENCE OF PENTECOSTALISM IN OKLAHOMA, 1909-1930 Thesis Approved: Dr. Bill Bryans Thesis Adviser Dr. Joseph Byrnes Dr. Michael Logan ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank my wife, Abigail, for the support over our entire marriage. Your importance to the completion of this work could fill a thesis. I want to thank our two little ones, Ranald & Thaddeus, who came to us throughout my graduate work. To my dad, Rolland Stanley Seaman, for all of his encouragement. My sister and brother for letting me make it out of childhood. To Dr. Michael Thompson for the kind words and guidance throughout my undergraduate career. To Dr. Lesley Rimmel and Dr. David D’Andrea were also very supportive voices during that time as well. To Dr. Ronald Petrin who helped me pick this topic. Dr. David Shideler for being a friend I should have listened to more often and his wife Tina, who is always (well, usually) right (but I’m mostly just thankful for the free food). To Dr. Tom and Marsha Karns for supporting my family and for their cabin, having that secluded space was worth more than gold to me. -

Grace AME Zion Church

Grace A. M. E. Zion Church This report was written on May 7, 1980. 1. Name and location of the property: The property known as the Grace A.M.E. Zion Church is located at 219-223 S. Brevard St. in Charlotte, N.C. 2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner and occupant of the property: The present owner and occupant of the property is: Grace A.M.E. Zion Church 219-223 S. Brevard St. Charlotte, N.C. 28202 Telephone: 332-7669 3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property. 4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property. 5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The original deed to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg County Deed Book 55, Page 444. Tax Parcel Number: 12502404. 6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains an historical essay on the property prepared by Dr. William H. Huffman. 7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains an architectural description of the property prepared by Jack O. Boyte, A.I.A. 8. Documentation of why and in what ways the property meets the criteria set forth in N. C. G. S. 160A-399.4: a. Special significance in terms of its history, architecture, and/or cultural importance: The Commission judges that the property known as the Grace A.M.E. Zion Church does possess special significance in terms of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The Commission bases its judgment on the following considerations: 1) the building, dedicated on July 13, 1902, is one of the oldest black churches in Charlotte and the only religious edifice which survives in what was once the largest black residential section in Charlotte, known as Brooklyn, 2) the church has contributed substantially to the evolution of the black community, especially through such members as Dr. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

m Fwm IO-m (Rev. I l-W) OMBNo. IW24Mll8 United States Department of the Interior National Park Sewice NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM Tiis form is for use in nominating or requesting &terminations for kdi\ldnal pmpntics or dismRs. See indamin How lo Complete the Na(tond Reglrrer of Htrroric Placer Re~mtrolronFonn @lstional Reginer BuU& 16A) Complcle sach itan by marking "x' in the appmpnrts box or by olleri~gIhc information requerled. If an itm doss not apply to the pmpmy king dmcntcd enln "NIA' far 'not applicable.' For btim,vchitsshwl clssrlflcanon materials, and areas of si@tificanee, mta only categories and ~bsntcgder6m Ihs inrmaions. Place additional mmcr and nam+tive ilsm m continualion sheet$ (NPS Form IO-ma) Uw a bWIs,word pnxcrrw. or canpnn, lo mp(c all itsmr. 1. Name of Propertv Historic name: LOMAX AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL ZION CHURCH Other nameslsite number: NDHR File Number 000-1 148) 2. Location Street & Number: 2704 24" Road South r NA 1Not for Publication Citv or town: r NA 1 Vicinitv State: Virginia Code: VA Countv: Arlington Code: 013 Zip Code: 22206 3. StateFederal Agency Certification & tk dc\,m~edsuhnr\ unlo thc N-sl I-lmmc Rew~tmnAn. as mdd 1 . rmlh. !ha hi I. XI . mnmtton I.. I rwuca. fw dcarmnnal!,n .lCLID~~III) -. mwtl ih~ dm~entationstandards for ~girtsMgpopfiierin thc National Rcdrta of Hislais Places and merIhs pddind pafesrional requiremolls ut fonh in 36 CFR Pan 60. In my aplrua~Ihs popem [X I meet$ [ ] dar not mac Ihs Nnional Regism ntctia. I rourmmcnd thhis proply be considered rimificant[ I nationally [ I rtamm\"de [XI locally / , Signature of certiGng officiflitle Date Virginia De~artmentof Historic Resources State or Federal agency and bureau h my opinion, ihc prop4y [ I meeu [I dosr nn mac the National Re$= stitma. -

© 2017 Christopher A. Howard ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2017 Christopher A. Howard ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BLACK INSURGENCY: THE BLACK CONVENTION MOVEMENT IN THE ANTEBELLUM UNITED STATES, 1830 – 1865 A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Christopher A. Howard August 2017 BLACK INSURGENCY: THE BLACK CONVENTION MOVEMENT IN THE ANTEBELLUM UNITED STATES, 1830 – 1865 Christopher A. Howard Dissertation Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Walter Hixson Dr. Martin Wainwright _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Elizabeth Mancke Dr. John C. Green _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Executive Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Zachery Williams Dr. Chand Midha _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Kevin Kern _________________________________ Committee Member Dr. Daniel Coffey ii ABSTRACT During the antebellum era, black activists organized themselves into insurgent networks, with the goal of achieving political and racial equality for all black inhabitants of the United States. The Negro Convention Movement, herein referred to as the Black Convention Movement, functioned on state and national levels, as the chief black insurgent network. As radical black rights groups continue to rise in the contemporary era, it is necessary to mine the historical origins that influence these bodies, and provide contexts for understanding their social critiques. This dissertation centers on the agency of the participants, and reveals a black insurgent network seeking its own narrative of liberation through tactics and rhetorical weapons. This study follows in the footing of Dr. Howard Holman Bell, who produced bodies of work detailing the antebellum Negro conventions published in the 1950s and 1960s. -

Methodist Denominations Referred to in This Book

METHODIST DENOMINATIONS REFERRED TO IN THIS BOOK African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.) An independent denomination founded by blacks in the North and border states as a protest against racial discrimination in the Methodist Episcopal Church. The A.M.E. Church held its inaugural General Conference in 1816 at Bethel Church in Philadelphia. Richard Allen was chosen to be the first bishop of the A.M.E. Church. In addi tion to being a Methodist minister, Allen was also one of the founders of a black mutual aid society called the Free African Society of Philadelphia. Allen also served as president of the first National Negro Convention, which took place in 1831 and was held at Bethel A.M.E. Church in Philadelphia. Allen's activism helped establish the values and objectives of the A.M.E. social gospel. African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (A.M.E. Zion) An independent de nomination founded by blacks in the North in 1822 as a protest against racial discrimination in the Methodist Episcopal Church and because of dissatisfac tion with the A.M.E. alternative.1 James Varick became the first superintendent of the denomination at its inaugural conference, which took place at Zion Church in New York City. In 1848 the new denomination officially adopted the name by which it is now known; before then it was called the A.M.E. Church, just like its Philadelphia-based sister denomination. Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in America (C.M.E.) An independent de nomination founded in 1870 in Jackson, Tennessee, by southern blacks with the assistance of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. -

James Varick James Varick

James Varick James Varick Civil Rights Pioneer Civil Rights Pioneer and First Bishop of the and First Bishop of the AME Zion Church AME Zion Church 1750-1827 1750-1827 Image courtesy of the General Image courtesy of the General Commission on Archives and History Commission on Archives and History orn in Newburgh, NY, Rev. James Varick began attending orn in Newburgh, NY, Rev. James Varick began attending Methodist services at the famed Rigging Loft in New York Methodist services at the famed Rigging Loft in New York BCity as a teenager. In time, he became a licensed local preacher BCity as a teenager. In time, he became a licensed local preacher in John Street Church. However, racist attitudes among New in John Street Church. However, racist attitudes among New York’s Methodists limited Varick’s opportunities to serve and York’s Methodists limited Varick’s opportunities to serve and lead the congregation. lead the congregation. Varick’s frustration with his congregation inspired him to take Varick’s frustration with his congregation inspired him to take bold action. In 1796, after securing Bishop Francis Asbury’s bold action. In 1796, after securing Bishop Francis Asbury’s blessing, Varick organized several of John Street’s African blessing, Varick organized several of John Street’s African American members into the city’s first church for people of American members into the city’s first church for people of col- color. Meeting first in his home, the new congregation moved or. Meeting first in his home, the new congregation moved into into a new building—Zion Church—in 1800. -

ROSSVILLE AME ZION CHURCH, 584 Bloomingdale Road, Staten Island Built: 1897; Andrew Abrams, Builder

Landmarks Preservation Commission February 1, 2011, Designation List 438 LP-2416 ROSSVILLE AME ZION CHURCH, 584 Bloomingdale Road, Staten Island Built: 1897; Andrew Abrams, builder Landmark Site: Borough of Staten Island Tax Map Block 7267, Lot 101 On August 10, 2010, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Rossville AME Zion Church and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were six speakers in favor of designation including a member of the Board of Trustees of the Rossville AME Zion Church who read a letter of support from Rev. Janet Jones. Other speakers on behalf of the designation included representatives of the Sandy Ground Historical Society, the Preservation League of Staten Island, the Society for the Architecture of the City, and the Historic Districts Council. The Commission has received two letters in support of the designation, including one from the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America. There were no speakers or letters in opposition. Summary The 1897 Rossville AME Zion Church is a rare and important surviving building from the period when Sandy Ground was a prosperous African American community on Staten Island. Beginning in the 1840s through the early 20th century, this area, called Woodrow, Little Africa, or (more commonly) Sandy Ground, was home to a group of free black people residing in more than 50 houses. For much of that time, many of the residents were employed in the oyster trade or in farming. -

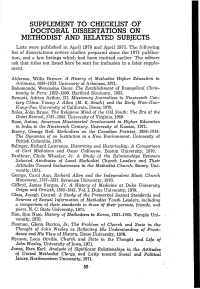

SUPPLEMENT to CHECKLIST of DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS on METHODIST and RELATED SUBJECTS Lists Were Published in April 1970 and April 1971

SUPPLEMENT TO CHECKLIST OF DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS ON METHODIST AND RELATED SUBJECTS Lists were published in April 1970 and April 1971. The following list of dissertations co'Q"ers studies prepared since the 1971 publica tion, and a f~w listings which had been omitted earlier. The editors ask that titles not listed here be sent for inclusion in a later supple ment. Alderson, Willis Brewer. A Histo1 o y of Methodist Higher Education in A1·kansas, 1836-1933. University of Arkansas, 1971. Bahamonde, Wenceslao Oscar. The Establishment of Evangelical Chris tianity in Peru: 1822-1900. Hartford Seminary, 1952. .Bennett, Adrian Arthur, III. Missionary Journalism in Nineteenth Cen tury China: Young J. Allen (M. E. South) and the Early Wan-Kuo Kung-Pao. University of California, Davis, 1970. Boles, John Bruce. The Religious Mind of the Old South: The Era of the Great Revival, 1787-1805. University of Virginia, 1969. Bose, Anima. American Missionaries' Involvement in Higher Education in Jndia in the Nineteenth Century.. University of Kansas, 1971. Emery, George Neil. Metliodism on the Canad~an Prairies, 1894-1914: . The Dynamics of an Institution in a New Environment. University of British Columbia, 1970. Eslinger, Richard.Lawrence. Historicity and Historicality: A Comparison of Carl Michalson and Oscar Cullmann. Boston University, 1970. Faulkner, Clyde Wheeler~ Jr. A Study of the Relationships Between Select~d Attributes of Local Methodist Church Leaders an4 ,Their Attitudes Toward Inclusiveness in the Methodist Church. Emory Uni- versity, 1971. .. ... George, .Carol Ann. Richard Allen and the Independent Black Church Movement, 1787-1831. Syracuse University, 1970. Gifford, James Fergus, Jr.