Reconstructing an Ancient Mining Landscape: a Multidisciplinary Approach to Copper Mining at Skouriotissa, Cyprus Vasiliki Kassianidou1,*, Athos Agapiou2,3 & Sturt W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Blue Beret

The Blue Beret Airborne The UNFICYP Magazine November/December 2011 Contents Editorial . .3 “Peacing” Cyprus together . .4 Inter-Mission Force Commanders’ Conference . .5 Unite to end violence . .6 Women in Peacekeeping/UNPOL Raises Serbian Flag/ New Faces in Maple Leaf Camp . .7 World AIDS Day Marked . .8/9 Culturally Significant Monuments in the Buffer Zone . .10/11 Service of Remembrance/Peace concert . .12 Honouring UNFICYP’s Fallen . .13 UN Staff Day . .14/15 Service for Peace Recognised . .16 New Bell for UN Flight / On duty in the ‘Magic Mansion’ . .17 UNFICYP Military Skills Competition . .18/19 Slovak Santa/ Carol Service . .20 Children visit Dhekelia SBA/ Cyprus Wedding for Liaison Officer . .21 New Faces . .22 Visits . .23 Serving UNFICYP’s civilian, military and police personnel The Blue Beret is UNFICYP’s in-house journal. Views expressed are of the authors concerned, and do not necessarily conform with official policy. Articles of general interest (plus photos with captions) are invited from all members of the Force Copyright of all material is vested in UN publications, but may be repro-duced with the Editor’s permission. The Blue Beret Editorial Team Unit Press Officers Published bi-monthly by the: Michel Bonnardeaux Sector 1 Capt. Marcelo Alejandro Quiroz Public Information Office Netha Kreouzos Sector 2 Capt. Matt Lindow United Nations Force in Cyprus Ersin Öztoycan Sector 4 Capt. 1Lt Jozef Zimmerman HQ UNFICYP Agnieszka Rakoczy MFR Capt. Alexander Hartwell PO Box 21642 1Sgt.Rastislav Ochotnicky UNPOL Deputy Senior Police Adviser 1590 Nicosia Cyprus (Photographer) Miroslav Milojevic Capt. Michal Harnadek UN Flt Lt. Jorgelina Camarzana FMPU Capt. -

Cyprus Copper Itinerary a Tour Through the Heart of Cyprus a Self-Drive Tour - Route 1 Cover: Rebuilt Copper Smelting Furnace No

Cyprus Copper Itinerary A tour through the heart of Cyprus A Self-Drive Tour - Route 1 Cover: Rebuilt Copper Smelting Furnace No. 8 from Agia Varvara-Almyras. This is the best preserved copper production unit in the entire Near East. List of contents Pages • Copper, its discovery and significance in shaping 1 the history of the island of Cyprus • Detailed itinerary 8 • Map of Cyprus with Copper Itinerary outlined 10 • Route information and timings 19 • Suggestions & useful telephone numbers 20 Copper: its discovery and significance in shaping the history of the island of Cyprus Cyprus, the third largest island in the Mediterranean after Sicily and Sardinia, was for many centuries the largest producer and exporter of copper to the ancient world. Pure copper or its alloys were a basic material needed for the development of large civilisations around the island. Without doubt, Cyprus with its copper contributed to the technological progress of the entire Mediterranean world and beyond. The creation of the island began approximately 90 million years ago in the sea floor of the ancient Tethys ocean. Extensive submarine volcanicity along the spreading axis of the sea floor permitted sea water to percolate into the deeper parts of the ocean floor close to magma and was as a consequence heated up to approximately 320 degrees celsius. This superheated water leached metallic elements from the rocks and was returned to the ocean through so called ‘Black Smokers’ where these elements were deposited to form the ore bodies, dominated by the copper and iron minerals we see now. Fig. 1 Fig. -

Copper and Foreign Investment: the Development of the Mining Industry in Cyprus During the Great Depression

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Copper and Foreign Investment: The development of the mining industry in Cyprus during the great depression Alexander Apostolides European University Of Cyprus, London School of Economics, University of Warwick, Department of Economics 11. April 2012 Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/43211/ MPRA Paper No. 43211, posted 3. May 2013 15:06 UTC Copper and Foreign Investment: The development of the mining industry in Cyprus during the great depression Dr. Alexander Apostolides, European University Cyprus Keywords: Cyprus, Interwar Economics, Mining, Cyprus Mining Corporation (CMC), Rio Tinto Abstract: This paper evaluates the impact of the rapid growth of mining on the Cypriot economy during the period 1921-1938, with special focus on the expansion of copper sulphate mining. During this period the industry was transformed by companies such as the Cyprus Mining Corporation (CMC) and this affected the whole economy and society. The island was for the first time inundated with substantial foreign direct investment, which encouraged technological adaptation and altered labour relations; as such there has been a debate on how beneficial was mining for the economy at that time. Using substantial primary data we estimated output (GDP share), employment and productivity estimates for the mining industry, as well as profit estimates for the foreign mining firms through the use of a counterfactual. The data allows us to argue that mining was very beneficial in increasing labour productivity and earning foreign exchange, but also highlights that the economic and social benefits for the economy were less than those suggested by the colonial authorities due to mass exports of profits. -

2930R67E UNFICYP May09.Ai

450000 E 500000 E 550000 E 600000 E 650000 32o 30' 33o 00' 33o 30' 34o 00' 34o 30' Cape Andreas 395000 N HQ UNFICYP 395000 N MEDITERRANEAN SEA HQ UNPOL Rizokarpaso FMPU Multinational UNPOL HQ Sector 2 Ayia Trias MFR Multinational Yialousa 35o 30' 35o 30' UNITED KINGDOM Vathylakas ARGENTINA Leonarisso UNPOL Ephtakomi SLOVAKIA Galatia Cape Kormakiti HQ Sector 1 Akanthou Komi Kebir 500 m Ardhana Karavas KYRENIA 500 m ARGENTINA Ayios Amvrosios Kormakiti Boghaz Lapithos Temblos HQ Sector 4 500 m Bellapais Trypimeni Dhiorios Myrtou Trikomo 500 m 500 m Famagusta ARGENTINA UNPOL Lefkoniko Bay SLOVAKIA / HUNGARY (-) K K. Dhikomo Chatos M . VE WE Bey Keuy WE XE 000 an P Skylloura 000 390 N so y ri Kythrea 390 N Ko u r VD WD a WD kk r g Morphou m Geunyeli K. Monastir UNPOL in a o SECTOR 1 m SLOVAKIA a s Bay a Strovilia Post Philia M Kaimakli LO Limnitis s Morphou Dhenia Angastina Prastio ro 0 90 Northing Selemant e Avlona 9 Northing X P. Zodhia UNPOL Pomos K. Trimithia NICOSIA Tymbou (Ercan) FAMAGUSTA 500 m Karavostasi UNPA s UNPOL s Cape Arnauti Lefka i Akaki SECTOR 2 o FMPU Multinational u it a Kondea Kalopsidha Khrysokhou Yialia iko r n Arsos m Varosha UNPOL el e o a b r g Bay m a m e UNPOL r Dherinia A s o t Athienou SECTOR 4 e is tr s t Linou 500 m s ri P Athna (Akhna) Mavroli rio A e 500 m u P Marki Prodhromi Polis ko Evrykhou Klirou Louroujina Troulli Paralimni 1000 m S 35o 00' o Pyla Ayia Napa 35 00' Kakopetria 500 mKochati Lymbia 1000 m DHEKELIA Cape 500 m Pedhoulas S.B.A. -

Photographic Exhibition Organized by the Cyprus Municipalities Under Turkish Military Occupation

PHOTOGRAPHIC EXHIBITION ORGANIZED BY THE CYPRUS MUNICIPALITIES UNDER TURKISH MILITARY OCCUPATION THE DESTRUCTION OF THE EUROPEAN CIVILIZATION OF CYPRUS BY TURKEY THE TRAGEDY GOES ON… “If we should hold our peace, the stones will cry out” (Luke 19: 40) THE DESTRUCTION OF THE EUROPEAN CIVILIZATION OF CYPRUS BY TURKEY THE TRAGEDY GOES ON… “If we should hold our peace, the stones will cry out” (Luke 19: 40) The photographic exhibition is organized by the nine occupied municipalities of Cyprus: Ammochostos, Kyrenia, Morphou, Lysi, Lapithos, Kythrea, Karavas, Lefkoniko, and Akanthou. The exhibition aims at sensitizing the broader public to the tragic consequences of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974. An effort is made to trace, as much as possible, the pain caused by the war and the uprooting of tenths of thousands of people from their homes. At the core of the presentation lies the systematic destruction of cultural heritage in the island’s occupied areas, which persists to this day as a result of ethnic cleansing and religious fanaticism. As proof of the above, damages to archaeological sites, ecclesiastical monuments and all non-Muslim cemeteries, as well as thefts intended to offer antiquities for sale at a profit, are showcased here. In some cases, photographic evidence which has been brought to light for the first time is put forth. This exhibition is divided into thematic units which are separated from one another by their different colours. Each panel includes a title and a brief text, whilst being supplemented by pertinent ‘before and after 1974’ visual material. The first unit introduces the nine occupied municipalities, with a historical outline, their most significant monuments and their present state. -

SEWERAGE SYSTEMS in CYPRUS National Implementation Programme Directive 91/271/EEC for the Treatment of Urban Waste Water

SEWERAGE SYSTEMS IN CYPRUS National Implementation Programme Directive 91/271/EEC for the treatment of Urban Waste Water Pantelis Eliades SiSenior EtiExecutive EiEngineer Head of the Wastewater and Re‐use Division Water Development Department «Water Treatment –Sewage» Spanish – Cypriot Partnering Event Hilton Hotel, Nicosia, 15 March 2010 Contents • Introduction • Requirements of the Directive 91/271/EEC • Implementation Programme of Cyprus(IP‐2008) – Description – CliCompliance DtDates – Current Situation – RidRequired IttInvestments / Financ ing • Collection Networks • Waste Water Treatment Plants • Re‐use of Treated Waste Water 2 Introduction • The Council Directive 91/271/EEC concerns the collection, treatment and discharge of urban wastewater with objective the protection of the environment. • According to Artilicle 17 of the Diiirective, Cyprus establish ed an Implementation Programme which concerns: – 57 Agglomerations – Population Equivalent(p.e.) 860.000 – Investments €1.430 million – Co‐Financ ing by EU €125 million • The Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment has the overall responsibility for the implementation of the Directive 3 Requirements of the Directive 91/271/EEC • Installation of collec tion netktworksand wastttewater tttreatmen t plants for secondary or equivalent treatment, in the agglomerations with population equivalent (p.e.) greater than 2000, (Articles 3 and 4) • More stringent treatment in sensitive areas which are subject to eutrophication – removal of Nitrogen and Phosphorus (Article 5) -

UNFICYP 2930 R100 Oct19 120%

450000 E 500000 E 550000 E 600000 E 650000 32o 30' 33o 00' 33o 30' 34o 00' 34o 30' Cape Andreas 395000 N HQ UNFICYP 395000 N MEDITERRANEAN SEA HQ UNPOL 联塞部队部署 Rizokarpaso FMPU Multinational UNFICYP DEPLOYMENT Ayia Trias DÉPLOIEMENT DE L’UNFICYP MFR UNITED KINGDOM Yialousa o o Vathylakas 35 30' 35 30' ДИСЛОКАЦИЯ ВСООНК ARGENTINA Leonarisso HQ Sector 2 DESPLIEGUE DE L A UNFICYP Ephtakomi ARGENTINA UNITED KINGDOM Galatia Cape Kormakiti SLOVAKIA Akanthou Komi Kebir UNPOL 500 m HQ Sector 1 Ardhana Karavas KYRENIA 500 m Kormakiti Lapithos Ayios Amvrosios Temblos Boghaz ARGENTINA / PARAGUAY / BRAZIL Dhiorios Myrtou 500 m Bellapais Trypimeni Trikomo ARGENTINA / CHILE 500 m 500 m Famagusta SECTOR 1 Lefkoniko Bay Sector 4 UNPOL VE WE K. Dhikomo Chatos WE XE HQ 390000 N UNPOL Kythrea 390000 N UNPOL VD WD ari WD XD Skylloura m Geunyeli Bey Keuy K. Monastir SLOVAKIA Mansoura Morphou am SLOVAKIA K. Pyrgos Morphou Philia Dhenia M Kaimakli Angastina Strovilia Post Kokkina Bay P. Zodhia LP 0 Prastio 90 Northing 9 Northing Selemant Limnitis Avlona UNPOL Pomos NICOSIA UNPOL 500 m Karavostasi Xeros UNPA Tymbou (Ercan) FAMAGUSTA UNPOL s s Cape Arnauti ti it a Akaki SECTOR 2 o Lefka r Kondea Kalopsidha Varosha Yialia Ambelikou n e o Arsos m m r a Khrysokhou a ro te rg Dherinia s t s Athienou SECTOR 4 e Bay is s ri SLOVAKIA t Linou A e P ( ) Mavroli rio P Athna Akhna 500 m u Marki Prodhromi Polis ko Evrykhou 500 m Klirou Troulli 1000 m S Louroujina UNPOL o o Pyla 35 00' 35 00' Kakopetria 500 mKochati Lymbia 1000 m DHEKELIA Ayia Napa Cape 500 m Pedhoulas SLOVAKIA S.B.A. -

SUPPLEMENT No. 3 Το the CYPRUS GAZETTE No. 4284 of 5TH DECEMBER, 1959. SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION. CONTENTS

SUPPLEMENT No. 3 το THE CYPRUS GAZETTE No. 4284 OF 5TH DECEMBER, 1959. SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION. CONTENTS The follozving SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION is published in this Supplement which forms / part of this Gazette :— PAGE , The Elections (President and Vice-President of the Republic) Laws, 1959.—Appointment 1/ of Assistant Returning Officers under Section 8 (2) .. .. .. .. .. 525 The Elections (President and Vice-President of the Republic) Laws, 1959.—The Elections (President and Vice-President of the Republic) (Greek Polling Districts) Regulations, 1959 " 525 No. 580. THE ELECTIONS (PRESIDENT AND VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC) LAWS, 1959. APPOINTMENT OF ASSISTANT RETURNING OFFICERS UNDER SECTION 8(2). In exercise of the powers vested in him by sub-section (2) of section 8 of the Elections (President and Vice-President of the Republic) Law, 1959, His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to appoint the following persons to be Assistant Returning Officers for the poll to be taken for the election of the President: — Christodoulos Benjamin. Yiangos Demetriou. Nicolaos Georghiou Lanitis. Zenon Christodoulou Vryonides. Philaretos Kasmiris. George Nathanael. Demetrakis Panteli Pantelides. Dated this 5th day of December, 1959. By His Excellency's Command, A. F. J. REDDAWAY, Administrative Secretary. No. 581. THE ELECTIONS (PRESIDENT AND VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC) LAWS, 1959. REGULATIONS MADE UNDER SECTIONS 19 (1) AND 43. In exercise of the powers vested in him by sections 19 (1) and 43 of the Elections (President and Vice-President of the Republic) Law, 1959, His 37 of 1959 Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has 41 of 1959· been pleased to make the following Regulations :— 1. -

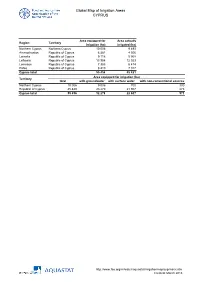

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for Area actually Region Territory irrigation (ha) irrigated (ha) Northern Cyprus Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 493 Ammochostos Republic of Cyprus 6 581 4 506 Larnaka Republic of Cyprus 9 118 5 908 Lefkosia Republic of Cyprus 13 958 12 023 Lemesos Republic of Cyprus 7 383 6 474 Pafos Republic of Cyprus 8 410 7 017 Cyprus total 55 456 45 421 Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Territory total with groundwater with surface water with non-conventional sources Northern Cyprus 10 006 9 006 700 300 Republic of Cyprus 45 449 23 270 21 907 273 Cyprus total 55 456 32 276 22 607 573 http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/irrigationmap/cyp/index.stm Created: March 2013 Global Map of Irrigation Areas CYPRUS Area equipped for District / Municipality Region Territory irrigation (ha) Bogaz Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 82.4 Camlibel Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 302.3 Girne East Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 161.1 Girne West Region Girne Main Region Northern Cyprus 457.9 Degirmenlik Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 133.9 Ercan Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 98.9 Guzelyurt Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 6 119.4 Lefke Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 600.9 Lefkosa Lefkosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 30.1 Akdogan Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 307.7 Gecitkale Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 71.5 Gonendere Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 45.4 Magosa A Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 436.0 Magosa B Magosa Main Region Northern Cyprus 52.9 Mehmetcik Magosa Main Region Northern -

The Mineral Industry of Cyprus in 2015

2015 Minerals Yearbook CYPRUS [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior July 2019 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Cyprus By Sinan Hastorun Cyprus, an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, stone increased by 567% compared with that of 2014; that of produced copper, umber and ocher, and industrial minerals used crushed limestone (havara), by 303%; umber and ocher for in construction. The production and export of other minerals cement production, by 175%; crude gypsum, by 36%; marble, or metals, such as asbestos fibers, chromite, gold, and silver, granules, and chippings, by 25%; calcined gypsum, by 17%; ceased in the early 1980s. The mineral resources of Cyprus1 and hydraulic cement, by 7%. The substantial increases were include asbestos, bentonite, copper, gypsum, lime, limestone from low base amounts produced during the recent economic (known locally as havara), marble, sand and gravel, and umber recession. Production of refined copper decreased by 28%; and ocher. In 2015, Cyprus accounted for about 0.8% of world clinker, clays for cement manufacture, and marl, by 10% each; bentonite production (table 1; Mines Service, 2016b, d, e; bentonite, by 9%; clay for brick and tile manufacture, hydrated Flanagan, 2017). lime, and iron oxide pigments (umber and ocher), by 8% each; In 2015, a new copper mine was being developed, which and sand and gravel, by 2% (table 1). would be the second metal mine in Cyprus. In 2015, mineral fuel reserves were reported for the first time after natural gas Structure of the Mineral Industry resources at the Aphrodite offshore field were determined to Table 2 is a list of the major mineral industry facilities, be commercially viable (EurActiv Energy News, 2015; Mines their locations, and their annual capacities. -

Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project

TAESP Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project Report on the Fourth Season, July-August 2003 Michael Given, Alexis Boutin, Brian Blankespoor, Hugh Corley, Stephen Digney, Erin Gibson, Angus Graham, Mara Horowitz, Vasiliki Kassianidou, A. Bernard Knapp, Abel Lufafa, Carole McCartney, Jay Noller, Colin Robins, Sheila Slevin, Luke Sollars, Thomas Tselios and Kristina Winther Jacobsen 30 September 2003 1. Introduction The Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Survey Project (TAESP) is studying the relationship between people and their environment from the Neolithic to the Modern period. Its 159 square kilometre survey area, on the northern slopes of the Troodos Mountains in central Cyprus, stretches from Skouriotissa and Kaliana in the west to Potami and Xyliatos in the east. TAESP is directed by Dr Michael Given (University of Glasgow), Dr Vasiliki Kassianidou (University of Cyprus), Prof. A. Bernard Knapp (University of Glasgow), and Prof. Jay Noller (Oregon State University). Our season ran from 5 July to 8 August, with 41 team members from eleven countries and eleven universities. TAESP is very grateful to the Department of Antiquities, and in particular to its Director Dr Sophocles Hadjisavvas, for permission to carry out this survey. We also thank Mr Antonis Nikolaides, the Mayor of Phlasou, Mr Pantelis Andreou Iakovou, the Mayor of Katydata, and Mr Georgios Papacharalambous, the Mayor of Tembria, for their generosity in allowing us to use the Phlasou, Katydata and Tembria schools and the Phlasou church hall. We have benefited greatly from the help and hospitality of the village councils and communities of Phlasou, Katydata, Tembria, Evrykhou, and the other villages in the survey area. -

Part a and B

CONFERENCE ON ACCESSION Brussels, 22 March 2001 TO THE EUROPEAN UNION - CYPRUS - CONF-CY 1/01 ADD 1 PUBLIC INFORMATION REQUESTED BY THE EU AND REVISED POSITIONS OF CYPRUS CHAPTER 7: AGRICULTURE ANNEX TO PART A AND B ____________________________________________________________________________ 20040/01 ADD 1 CONF-CY 1/01 1 EN Conseil UE ANNEX TO PART A TABLE Α.1 Characteristics of rural communities in areas classified as highly disadvantaged and deprived (non-exhaustive list) SN District Commu- Agro- Community Altitude Area Population Holders with Farm nity code economic (m) (km2) change 1976- main income per Region 1992 occupation labour unit (%) agriculture [(+) or (-) of (%) 80% of the National average] (C£) 1 Larnaca 4310 209 Kato Lefkara 470 11,589 -43,0 59,5 -1.122 2 " 4311 209 Pano Lefkara 575 62,163 -39,2 50,5 653 3 " 4312 209 Kato Drys 500 13,678 -54,3 54,8 1.148 4 " 4313 209 Vavla 455 9,815 -38,9 86,6 4.046 5 " 4314 209 Lageia 360 10,213 -51,1 85,7 220 6 " 4315 209 Ora 530 27,112 -39,7 60,5 -211 7 " 4316 209 Melini 600 7,552 -41,6 55,0 -1.071 8 " 4317 209 Odou 760 11,847 -36,8 75,7 874 9 " 4318 209 Ag. Vavatsinias 720 15,447 -32,4 41,3 1.050 10 " 4319 209 Vavatsinia 865 14,585 -55,2 50,0 360 11 Limassol 5131 215 Vasa Kellakiou 365 16,450 -30,8 33,3 -1.097 12 " 5132 215 Sanida 605 10,698 -18,2 58,8 1.574 13 " 5133 215 Prastio Kellakiou 380 17,199 -43,2 53,6 -1.885 14 " 5134 215 Klonari 455 3,231 -15,0 83,3 973 15 " 5135 215 Vikla 455 3,942 -100,0 - -3.228 16 " 5136 215 Kellaki 600 9,253 -14,9 53,9 2.524 17 " 5137 215 Akapnou 365 6,668 -59,5 81,8 1.314 18 " 5138 215 Eptagoneia 455 12,105 -15,8 59,3 108 19 " 5140 215 Dierona 730 23,029 -5,9 39,1 -1.772 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 20040/01 ADD 1 CONF-CY 1/01 2 EN ANNEX TO PART A 20 Limassol 5141 215 Arakapas 650 12,423 -18,9 41,6 -729 21 " 5144 215 Sykopetra 760 14,071 -57,2 48,7 -1.795 22 " 5105 318 Gerasa 335 10,282 -56,5 48,4 -892 23 " 5106 318 Apsiou 395 20,675 -35,8 42,9 -538 24 " 5142 318 Ag.