Doha Meeting for Advancing Religious Freedom Through Interfaith Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light on the Darkness

Fall 2016 the FlameTHE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY LIGHT ON THE DARKNESS Psychology alumna Jean Maria Arrigo dedicated 10 years of her life to exposing the American Psychological Association’s secret ties to US military interrogation efforts MAKE A GIFT TO THE ANNUAL FUND TODAY the Flame Claremont Graduate University THE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY fellowships play an important role Fall 2016 The Flame is published by in ensuring our students reach their Claremont Graduate University’s Office of Marketing and Communications educational goals, and annual giving 165 East 10th Street Claremont, CA 91711 from our alumni and friends is a ©2016 Claremont Graduate University major contributor. Here are some of VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT our students who have benefitted Ernie Iseminger ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS from the CGU Annual Fund. Max Benavidez EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Andrea Gutierrez “ I am truly grateful for the support that EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ADVANCEMENT COMMUNICATIONS CGU has given me. This fellowship has Nicholas Owchar provided me with the ability to focus MANAGING EDITOR on developing my career.” Roberto C. Hernandez Irene Wang, MBA and MA DESIGNER Shari Fournier-O’Leary in Management DIRECTOR, DESIGN SERVICES Gina Pirtle I received fellowship offers from other ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, INTEGRATED MARKETING “ Alfie Christiansen schools. But the amount of my fellowship ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS from CGU was the biggest one, and Sheila Lefor I think that is one of my proudest DISTRIBUTION MANAGER moments.” Mandy Bennett Akihiro Toyoda, MBA PHOTOGRAPHERS Carlos Puma John Valenzuela If I didn’t have the fellowship, there is William Vasta “ Tom Zasadzinski no way I would have been able to study for a PhD. -

A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (Guest Post)*

“A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (guest post)* Garrison Keillor “Well, it's been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, Minnesota, my hometown, out on the edge of the prairie.” On July 6, 1974, before a crowd of maybe a dozen people (certainly less than 20), a live radio variety program went on the air from the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, MN. It was called “A Prairie Home Companion,” a name which at once evoked a sense of place and a time now past--recalling the “Little House on the Prairie” books, the once popular magazine “The Ladies Home Companion” or “The Prairie Farmer,” the oldest agricultural publication in America (founded 1841). The “Prairie Farmer” later bought WLS radio in Chicago from Sears, Roebuck & Co. and gave its name to the powerful clear channel station, which blanketed the middle third of the country from 1928 until its sale in 1959. The creator and host of the program, Garrison Keillor, later confided that he had no nostalgic intent, but took the name from “The Prairie Home Cemetery” in Moorhead, MN. His explanation is both self-effacing and humorous, much like the program he went on to host, with some sabbaticals and detours, for the next 42 years. Origins Gary Edward “Garrison” Keillor was born in Anoka, MN on August 7, 1942 and raised in nearby Brooklyn Park. His family were not (contrary to popular opinion) Lutherans, instead belonging to a strict fundamentalist religious sect known as the Plymouth Brethren. -

Augustana Book Club History and Selections 2001-Present from the Church Bulletins in Oct

Augustana Book Club History and Selections 2001-present From the church bulletins in Oct. 2001: "Book Club coming soon. Are YOU interested?" Meeting set for 7 pm Oct. 23 in the church library "The first meeting will be a time to plan our reading and meeting places." Contact Joanne Mecklem or Amy Plumb Book Author 2001 Oct. FIRST MEETING Nov. The Samurai's Garden Gail Tsukiyama Dec. Martin Luther's Christmas Book Martin Luther 2002 Jan. Dakota Kathleen Norris Feb. Reservation Blues Sherman Alexie March The Bridge Doug Marlett April Teaching a Stone to Talk Annie Dillard May NO MEETING June To Know a Woman Amos Oz July NO MEETING Aug. "Book Potluck"--Share a summertime read Sept. The Poisonwood Bible Barbara Kingsolver Oct. Bel Canto Ann Patchett Nov. The Lovely Bones Alice Sebold Father Melancholy's Daughter @ Cooke Dec. Gail Godwin First book club hosted at a home and not church library 2003 A Lesson Before Dying @ Wackers (Everybody Reads) Jan. We have read each MultCo Library Everybody Reads selection since Ernest Gaines the program began in Winter 2003 A Fine Balance @ Van Winkles Feb. In the bulletin: "Over the next months the group will be meeting in homes Rohinton Mistry and enjoying potluck with a book-inspired menu." March Bless Me, Ultima @ Kindschuhs Rudolfo Anaya Choice of books @ Ranks: The Clash of Civilizations & the Remaking of the World Order Samuel Huntington Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fate of Human Societies Jared Diamond April The Wealth of Nations David Landers Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress ed.Lawrence Harrison,Samuel Huntington Islam: An Introduction for Christians ed.Paul V. -

Lake Wobegon Days Loretta Wasserman Grand Valley State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarworks@GVSU Grand Valley Review Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 17 1-1-1986 Lake Wobegon Days Loretta Wasserman Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr Recommended Citation Wasserman, Loretta (1986) "Lake Wobegon Days," Grand Valley Review: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 17. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr/vol1/iss1/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grand Valley Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 62 IDRETTA WASSERMAN Early chapte it New Albion Lake Wobegon Days man Catholics and happenin~ Lake Wobegon Days by Garrison Keillor, Viking Press, $17.95. tions - the ol1 and the preser Nineteen eighty-five saw the publication of an odd book of humor that was an of free associa astonishing success - astonishing at least to those of us who thought our fondness Keillor clear for Garrison Keillor's radio stories about Lake Wobegon, Minnesota ("the little town transcendenta that time forgot"), marked us as members of a smallish group: not a cult (fanaticism of Minnesota. of any kind not being a Wobegon trait), but still a distinct spectrum. Not so, apparently. Alcott is the s At year's end was at the very top of the charts, where it stayed Lake Wobegon Days Rain Dance a1 for several weeks, and had sold well over a million copies. -

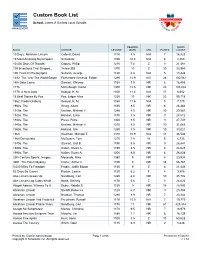

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: James A Garfield Local Schools MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT 10 Days: Abraham Lincoln Colbert, David 1110 8.5 N/A 7 16,823 10 Most Amazing Skyscrapers Scholastic 1100 10.4 N/A 6 8,263 10,000 Days Of Thunder Caputo, Philip 1210 7.6 Z 8 21,491 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 10 Z 10 33,959 100 Years In Photographs Sullivan, George 1120 6.8 N/A 5 13,426 1492: The Year The World Began Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe 1280 12.9 N/A 24 100,581 14th Dalai Lama Stewart, Whitney 1130 7.9 NR 6 18,455 1776 McCullough, David 1300 12.5 NR 23 105,034 1776: A New Look Kostyal, K. M. 1100 11.4 N/A 17 6,652 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 10 NR 22 99,118 1862, Fredericksburg Kostyal, K. M. 1160 11.6 N/A 5 7,170 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 8.5 NR 8 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 8.5 NR 10 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 8.5 NR 9 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 8.5 NR 9 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 8.5 NR 10 31,665 1960s, The Holland, Gini 1260 8.5 NR 10 33,021 1968 Kaufman, Michael T. 1310 10.9 N/A 11 36,546 1968 Democratic McGowen, Tom 1270 7.8 W 5 6,733 1970s, The Stewart, Gail B. -

AILACTE Journal 69 Perfect Storm

Perfect Storm Hits Georgia Schools: Teachers Overwhelmed Dara V. Wakefield, Ed.D. Berry College Abstract No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Race to the Top (RT3) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) have piled up federal mandates into a “perfect storm” for Georgia teachers. This study considers the impact of this storm through the eyes of 23 Georgia teachers. A tidal wave of federal mandates leaves teachers over- whelmed and skeptical about their future. Keywords: : NCLB, RT3, Georgia Teachers, Classroom Change, Federal Mandates AILACTE Journal 69 Wakefield Dr. Larry Cuban, education historian, policymaker and pro- fessor at Stanford University, associated education reforms with weather cycles in The Inexorable Cycles of School Reform (2011). He stated, “Reforms, like weather fronts varying by seasons but similar across years, go through phases that become familiar if observers note historical patterns” (Cuban, 2011). Those with a few decades of public education under their belts have seen “reform” fronts blow through with every election cycle. During this study, a “perfect storm” hit and teachers were sent running for their umbrellas and boots. This particular cycle is remarkable because it comes on the heels of the collapse of the “No Child Left Behind” (NCLB) Act (U.S. Department of Education, 2001). States filed for U.S. Department of Education NCLB waivers because they could not meet the 100% pass rates on Annual Yearly Progress (AYP) by 2015. At the same time, 18 Race to the Top (RT3) states and those with NCLB waiv- ers—almost all states—were required to implement RT3 mandates (U.S. Department of Education, 2009) (Ravich, 2015). -

Cahiers De Littérature Orale, 75-76 | 2014 the Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page 2

Cahiers de littérature orale 75-76 | 2014 L'autre voix de la littérature The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page Garrison Keillor’s Radio Romance Flore Coulouma Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/clo/1884 DOI: 10.4000/clo.1884 ISSN: 2266-1816 Publisher INALCO Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2014 ISBN: 978-2-85831-222-1 ISSN: 0396-891X Electronic reference Flore Coulouma, “The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page”, Cahiers de littérature orale [Online], 75-76 | 2014, Online since 29 April 2015, connection on 02 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/clo/1884 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/clo.1884 This text was automatically generated on 2 July 2021. Cahiers de littérature orale est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale 4.0 International. The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page 1 The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page Garrison Keillor’s Radio Romance Flore Coulouma Introduction 1 American author and radio personality Garrison Keillor has been described as “a brilliant writer, monologist and sometime crooner” and “arguably the biggest star in the world of public radio” (Smith, 2012; Carter, 2011). He is also listed as a “storyteller” on the popular American blog The Moth, home of a non-profit cultural organization devoted to oral storytelling. Besides hosting his acclaimed radio program A Prairie Home Companion, Keillor has published novels, short-story collections and poetry, and contributes columns and stories to the New York Times, The New Yorker and National Geographic, among others. -

Radiolovefest 2016

BAM 2016 Winter/Spring Season #RadioLoveFest Brooklyn Academy of Music New York Public Radio Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board Cynthia King Vance, Chair, Board of Trustees William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board John S. Rose, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Susan Rebell Solomon, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Katy Clark, President Mayo Stuntz, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Laura R. Walker, President & CEO BAM and WNYC present RadioLoveFest Produced by BAM and WNYC March 10—12 LIVE PERFORMANCES Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me!®, NPR®, Mar 10, 7:30pm, OH Into The Deep: The Moth at BAM, Mar 10, 7:30pm, HT Laura Poitras and Edward Snowden—Interviewed by Brian Lehrer, Mar 11, 7:30pm, OH Selected Shorts: Dangers and Discoveries—A Presentation of Symphony Space, Mar 11, 7:30pm, HT Garrison Keillor: Radio Revue, Mar 12, 7:30pm, OH Death, Sex & Money, Mar 12, 7:30pm, HT SCREENINGS—7:30pm, BRC BAMCAFÉ LIVE—9:30pm, BC, free Scream, host: Sean Rameswaram, Mar 11 Curated by Terrance McKnight A League of Their Own, host: Molly Webster, Mar 12 PUBLIQuartet, Mar 11 Addi & Jacq, Mar 12 Season Sponsor: American Express is the Founding Sponsor of RadioLoveFest. Delta is the Official Airline of RadioLoveFest. VENUE KEY Major support provided by the Joseph & Diane Steinberg Charitable Trust. BC=BAMcafé BRC=BAM Rose Cinemas Forest City Ratner Companies is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. HT=BAM Harvey Theater OH=BAM Howard Gilman Support for the Signature Artist Series provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation. -

Wobegonian Modesty and Garrison Keilor's Lake Wobegon Days

Wobegonian Modesty and Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon Days Richard Newman Lake Wobegon survives to the extent that it does on a form of voluntary socialism with elements of Deism, fatalism, and nepotism. – Garrison Keilor, Lake Wobegon Days 1 The humble Midwestern town also survives on modesty and a range of satellite sentiments and postures, depending very much on them in Garrison Keillor’s 1985 book Lake Wobegon Days. It is, firmly, a work of pastoral—a literary representation of social, emotional, and aesthetic dualities and tensions in the frame, or in mind, of rural or regional place. Its vital and interesting connection to this mode depends, critically, on its not being the work of blandly sentimentalist affirmation or sugared “nostalgia for the simple life” 2 that mode is commonly seen as. Structurally, too, it is more complicatedly a somewhat loose or meandering assemblage than a novel, organised—such as it is—variously by the seasons, the growth of its narrating figures, and progression through the town’s semi-factual history. It is not quite part of, but gamely enacts in a local sphere, “the long tradition in America of insisting on taking into account the whole being of the American and the entire swath of the country’s history.” 3 The book is, accordingly, quite long, at 502 pages. Tellingly, it opens with a preface COLLOQUY text theory critique 23 (2012). © Monash University. www.arts.monash.edu.au/ecps/colloquy/journal/issue023/newman.pdf ░ Wobegonian Modesty and Keillor’s Lake Wobegon Days 119 directly from Keillor’s perspective (something he later distorts and toys with throughout the book), which describes the Hemingway-esque loss of a manuscript—two unrepeatably perfect short stories—at the Portland train station. -

David Garrard's Summa Cum Season

spring 2008 EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy David garrard’s summa cum season viewfinDer spring 2008 EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy 12 FEATUrEs SUMMA CUM SEASON 12 Six years after graduating from ECU holding 28 schoolBy Steve football Tuttle records, David Garrard enjoys a stellar season in the NFL leading the Jacksonville Jaguars. But the crowning achievement of the year to this committed family man is the birth of a son. ATTorney Privilege 20 Greenville attorney Phil Dixon is grateful for his collegeBy Steve education Row and constantly gives back as an advocate for ECU on the UNC Board of Governors. An expert on education policy, 26 he’s advised local school boards and community colleges for decades. A Banner DAY FOR learning 26 East Carolina goes live on a new computer softwareBy Bethany platform Bradsher called Banner that gives students far greater online access to course materials. The new system enhances student privacy while opening a door into the virtual classroom. A laptop can store amazing LAPPing The CoMPeTiTion amounts of 30 Quick—name the ECU sports team that has information, but threeBy Bethany national Bradsher championships and just set a school record for senior Mary Lyons consecutive winning seasons. No, it’s swimming and diving, which has learned that no lapped the competition for the 25th straight year. computer can match the learning experience achieved the old-fashioned way—reading a book. DEpArTMEnTs froM oUr reaDers 3 20 The eCU rePorT 5 30 sPring arTs CalenDar 10 PiraTe naTion 36 CLASS noTes 3 9 48 UPon The PAST froM The eDiTor froM oUr reaDers spring 2008 EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy Volume 6, Number 3 Members of I saw the picture and caption in the last is published four times a year by rchives the 1958 Rebel a issue of about the and its 50th read East on your computer East East Carolina University staff, from left, anniversary.East I was editorRebel in 1960–61. -

Download Waterways Adult Reading List

Water/Ways Adult Reading List This resource list was assembled to help you research and develop exhibitions and programming around the themes of the Water/ Ways exhibition. Work with your local library or bookstore to host book clubs, discussion programs or other learning opportunities in conjunction with the exhibition, or develop a display with books on the subject. This list is not meant to be exhaustive or even all-encompassing – it will simply get you started. A quick search of the library card catalogue or internet will reveal numerous titles and lists compiled by experts, backyard scientists and beachcombers alike. You will also find blogs, chat groups and author interviews, etc. All titles should be readily available unless otherwise specified. Adult Fiction Jonis Agee. The River Wife: A Novel. Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reprint Edition, 2008. 432 pages. The River Wife features interwoven narratives of two women living in the same house along the river over 100 years apart. One story begins in the early 1800s with Annie Lark marrying a strong, brooding fur trader, Jacques Ducharme, and she lives out her life as his “River Wife”. In the 1930s, Hedie Rails married Clement Ducharme, a decedent of Annie’s husband and they begin their life in the very house Jacques built for Annie. Hedie discovers Annie’s haunting journals, and beings to read about Annie’s family life, which directly impacts her own. Richard Bach (Author), Russell Munson (Photographer). Jonathan Livingston Seagull: the Complete Edition, Scribner; Reissue edition, 2014. 144 pages. Set on the water and beach, this is the story for people who follow their hearts and make their own rules…people who get special pleasure out of doing something well, even if only for themselves…people who know there’s more to this living than meets the eye: they’ll be right there with Jonathan, flying higher and faster than they ever dreamed. -

2015-2016 Season } Greetings! }

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA PERFORMING ARTS 2015-2016 SEASON } GREETINGS! } It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to the 2015-2016 University of Florida Performing Arts (UFPA) Season which captures the essence of the program we have had during my 15 years as director. The essence or summation of these varied events include diversity, innovation and excellence. Opetaia Foai’i’s Polynesian band, TE VAKA, Celtic Nights – Spirit of Freedom, celebrating Irish independence, and, a night of international guitar virtuosi uphold UFPA’s longstanding tradition of echoing the university’s ever-growing diverse population and internationalization initiatives. Young concert artists will continue to be a feature of our offerings with a highlight performance of the rising stars of the Metropolitan Opera in repertory from their upcoming season as well as our array of soloists. A uniquely framed contemporary program by the Art of Time Ensemble will present the entirety of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in a uniquely innovative and artistically interpreted program that is far from a “cover band approach to the iconic work.” The evening will include two violins, two violas, two cellos, and one each of double bass, guitar, saxophone/clarinet, trumpet and drums/percussion and piano. UFPA has established itself as one of the most sought-after facilities to mount productions before heading on national and international tours. Past productions mounted in our venue have received great acclaim, such as the Pulitzer Prize Finalist, Steel Hammer. This season has the “building-for-touring” of Ragtime along with the creation and world premiere of an a cappella performance titled Vocalosity: The Aca-perfect Concert Experience, created by Deke Sharon the vocal producer of the Pitch Perfect films.