Wobegonian Modesty and Garrison Keilor's Lake Wobegon Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light on the Darkness

Fall 2016 the FlameTHE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY LIGHT ON THE DARKNESS Psychology alumna Jean Maria Arrigo dedicated 10 years of her life to exposing the American Psychological Association’s secret ties to US military interrogation efforts MAKE A GIFT TO THE ANNUAL FUND TODAY the Flame Claremont Graduate University THE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY fellowships play an important role Fall 2016 The Flame is published by in ensuring our students reach their Claremont Graduate University’s Office of Marketing and Communications educational goals, and annual giving 165 East 10th Street Claremont, CA 91711 from our alumni and friends is a ©2016 Claremont Graduate University major contributor. Here are some of VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT our students who have benefitted Ernie Iseminger ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS from the CGU Annual Fund. Max Benavidez EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Andrea Gutierrez “ I am truly grateful for the support that EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ADVANCEMENT COMMUNICATIONS CGU has given me. This fellowship has Nicholas Owchar provided me with the ability to focus MANAGING EDITOR on developing my career.” Roberto C. Hernandez Irene Wang, MBA and MA DESIGNER Shari Fournier-O’Leary in Management DIRECTOR, DESIGN SERVICES Gina Pirtle I received fellowship offers from other ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, INTEGRATED MARKETING “ Alfie Christiansen schools. But the amount of my fellowship ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS from CGU was the biggest one, and Sheila Lefor I think that is one of my proudest DISTRIBUTION MANAGER moments.” Mandy Bennett Akihiro Toyoda, MBA PHOTOGRAPHERS Carlos Puma John Valenzuela If I didn’t have the fellowship, there is William Vasta “ Tom Zasadzinski no way I would have been able to study for a PhD. -

A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (Guest Post)*

“A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (guest post)* Garrison Keillor “Well, it's been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, Minnesota, my hometown, out on the edge of the prairie.” On July 6, 1974, before a crowd of maybe a dozen people (certainly less than 20), a live radio variety program went on the air from the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, MN. It was called “A Prairie Home Companion,” a name which at once evoked a sense of place and a time now past--recalling the “Little House on the Prairie” books, the once popular magazine “The Ladies Home Companion” or “The Prairie Farmer,” the oldest agricultural publication in America (founded 1841). The “Prairie Farmer” later bought WLS radio in Chicago from Sears, Roebuck & Co. and gave its name to the powerful clear channel station, which blanketed the middle third of the country from 1928 until its sale in 1959. The creator and host of the program, Garrison Keillor, later confided that he had no nostalgic intent, but took the name from “The Prairie Home Cemetery” in Moorhead, MN. His explanation is both self-effacing and humorous, much like the program he went on to host, with some sabbaticals and detours, for the next 42 years. Origins Gary Edward “Garrison” Keillor was born in Anoka, MN on August 7, 1942 and raised in nearby Brooklyn Park. His family were not (contrary to popular opinion) Lutherans, instead belonging to a strict fundamentalist religious sect known as the Plymouth Brethren. -

So Long, Lake Wobegon? Using Teacher Evaluation to Raise Teacher Quality

FLICKR.COM/ O LD WOMAN SHOE WOMAN LD So Long, Lake Wobegon? Using Teacher Evaluation to Raise Teacher Quality Morgaen L. Donaldson June 2009 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG So Long, Lake Wobegon? Using Teacher Evaluation to Raise Teacher Quality Morgaen L. Donaldson June 2009 Executive summary In recent months, ideas about how to improve teacher evaluation have gained prominence nationwide. In April, 2009, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan proposed that districts report the percentage of teachers rated in each evaluation performance category. Michelle Rhee, chancellor of the Washington, D.C. public schools, has proposed evaluating teach- ers largely on the basis of their students’ performance. Georgia and Idaho have launched major efforts to reform teacher evaluation at the state level. Meanwhile, researchers have noted that a well-designed and implemented teacher evaluation system may be the most effective way to raise student achievement.1 And teacher evaluation reaches schools and districts in every corner of the country, positioning it to affect important aspects of school- ing such as teacher collaboration and school culture, in addition to student achievement. Historically, teacher evaluation has not substantially improved instruction or expanded student learning. The last major effort to reform teacher evaluation, in the 1980s, petered out after much fanfare. Today there are reasons to believe that conditions are right for substantive improvements to evaluation. Important advances in our knowledge of effective teaching practices, shifts in the composition of the educator workforce, and changes in the context of public education provide a key opportunity for policymakers to tighten the link between teacher evaluation and student learning. -

DOLLAR GENERAL 100 Angelfish Ave Avon, MN (St

NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DOLLAR GENERAL 100 Angelfish Ave Avon, MN (St. Cloud MSA) TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Profile II. Location Overview III. Market & Tenant Overview Executive Summary Aerial Demographic Report Investment Highlights Site Plan Market Overview Property Overview Map Tenant Overview NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DISCLAIMER STATEMENT DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Offering Memorandum is proprietary and strictly confidential. STATEMENT: It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from The Boulder Group and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of The Boulder Group. This Offering Memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. The Boulder Group has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation. The information contained in this Offering Memorandum has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, The Boulder Group has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has The Boulder Group conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE The Boulder Group is pleased to exclusively market for sale a single tenant net leased Dollar General property SUMMARY: located within the St. -

Augustana Book Club History and Selections 2001-Present from the Church Bulletins in Oct

Augustana Book Club History and Selections 2001-present From the church bulletins in Oct. 2001: "Book Club coming soon. Are YOU interested?" Meeting set for 7 pm Oct. 23 in the church library "The first meeting will be a time to plan our reading and meeting places." Contact Joanne Mecklem or Amy Plumb Book Author 2001 Oct. FIRST MEETING Nov. The Samurai's Garden Gail Tsukiyama Dec. Martin Luther's Christmas Book Martin Luther 2002 Jan. Dakota Kathleen Norris Feb. Reservation Blues Sherman Alexie March The Bridge Doug Marlett April Teaching a Stone to Talk Annie Dillard May NO MEETING June To Know a Woman Amos Oz July NO MEETING Aug. "Book Potluck"--Share a summertime read Sept. The Poisonwood Bible Barbara Kingsolver Oct. Bel Canto Ann Patchett Nov. The Lovely Bones Alice Sebold Father Melancholy's Daughter @ Cooke Dec. Gail Godwin First book club hosted at a home and not church library 2003 A Lesson Before Dying @ Wackers (Everybody Reads) Jan. We have read each MultCo Library Everybody Reads selection since Ernest Gaines the program began in Winter 2003 A Fine Balance @ Van Winkles Feb. In the bulletin: "Over the next months the group will be meeting in homes Rohinton Mistry and enjoying potluck with a book-inspired menu." March Bless Me, Ultima @ Kindschuhs Rudolfo Anaya Choice of books @ Ranks: The Clash of Civilizations & the Remaking of the World Order Samuel Huntington Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fate of Human Societies Jared Diamond April The Wealth of Nations David Landers Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress ed.Lawrence Harrison,Samuel Huntington Islam: An Introduction for Christians ed.Paul V. -

Deepening Discipleship Table South Carolina Synod Assembly 2021

BULLETIN OF REPORTS CHAPTER FOUR - 1 Deepening Discipleship Table South Carolina Synod Assembly 2021 Dear Partners in the Gospel, I have taken great delight in Garrison Keillor’s book entitled “Life among the Lutherans”. It is a wonderful walk through “his hometown, Lake Wobegon” in Minnesota, which in actuality is a collection of his talk’s on his radio show on public radio, A Prairie Home Companion. As we of the South Carolina Synod discern our calling to discipleship for our Lord Christ Jesus, Keillor shares some apt thoughts. They can make us blush and smile but also empower us to deepen our discipleship as we share the Gospel. He writes on page 3: “The people who occupy the pews of Lake Wobegon Lutheran on Sunday are ordinary people, doing their best to be good and walk straight in a world that seems to reward the crooked and mock the righteous. They gather and give alms to the poor; they sing, "Lift every voice and sing till earth and heaven ring," so that tears come to your eyes; and they pray to God, "Create in me a clean heart, 0 God, and renew a right spirit within me. Cast me not away from thy presence and take not thy Holy Spirit from me. Restore unto me the joy of thy salvation…" And then they go home and put on their work clothes and tend their flowerbeds and groom their lawns. While they do their best to love each other, they also watch each other very closely, there is gossip, on occasion. -

Lake Wobegon Days Loretta Wasserman Grand Valley State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarworks@GVSU Grand Valley Review Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 17 1-1-1986 Lake Wobegon Days Loretta Wasserman Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr Recommended Citation Wasserman, Loretta (1986) "Lake Wobegon Days," Grand Valley Review: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 17. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr/vol1/iss1/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grand Valley Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 62 IDRETTA WASSERMAN Early chapte it New Albion Lake Wobegon Days man Catholics and happenin~ Lake Wobegon Days by Garrison Keillor, Viking Press, $17.95. tions - the ol1 and the preser Nineteen eighty-five saw the publication of an odd book of humor that was an of free associa astonishing success - astonishing at least to those of us who thought our fondness Keillor clear for Garrison Keillor's radio stories about Lake Wobegon, Minnesota ("the little town transcendenta that time forgot"), marked us as members of a smallish group: not a cult (fanaticism of Minnesota. of any kind not being a Wobegon trait), but still a distinct spectrum. Not so, apparently. Alcott is the s At year's end was at the very top of the charts, where it stayed Lake Wobegon Days Rain Dance a1 for several weeks, and had sold well over a million copies. -

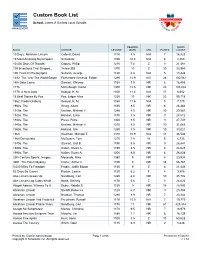

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: James A Garfield Local Schools MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT 10 Days: Abraham Lincoln Colbert, David 1110 8.5 N/A 7 16,823 10 Most Amazing Skyscrapers Scholastic 1100 10.4 N/A 6 8,263 10,000 Days Of Thunder Caputo, Philip 1210 7.6 Z 8 21,491 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 10 Z 10 33,959 100 Years In Photographs Sullivan, George 1120 6.8 N/A 5 13,426 1492: The Year The World Began Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe 1280 12.9 N/A 24 100,581 14th Dalai Lama Stewart, Whitney 1130 7.9 NR 6 18,455 1776 McCullough, David 1300 12.5 NR 23 105,034 1776: A New Look Kostyal, K. M. 1100 11.4 N/A 17 6,652 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 10 NR 22 99,118 1862, Fredericksburg Kostyal, K. M. 1160 11.6 N/A 5 7,170 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 8.5 NR 8 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 8.5 NR 10 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 8.5 NR 9 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 8.5 NR 9 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 8.5 NR 10 31,665 1960s, The Holland, Gini 1260 8.5 NR 10 33,021 1968 Kaufman, Michael T. 1310 10.9 N/A 11 36,546 1968 Democratic McGowen, Tom 1270 7.8 W 5 6,733 1970s, The Stewart, Gail B. -

AILACTE Journal 69 Perfect Storm

Perfect Storm Hits Georgia Schools: Teachers Overwhelmed Dara V. Wakefield, Ed.D. Berry College Abstract No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Race to the Top (RT3) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) have piled up federal mandates into a “perfect storm” for Georgia teachers. This study considers the impact of this storm through the eyes of 23 Georgia teachers. A tidal wave of federal mandates leaves teachers over- whelmed and skeptical about their future. Keywords: : NCLB, RT3, Georgia Teachers, Classroom Change, Federal Mandates AILACTE Journal 69 Wakefield Dr. Larry Cuban, education historian, policymaker and pro- fessor at Stanford University, associated education reforms with weather cycles in The Inexorable Cycles of School Reform (2011). He stated, “Reforms, like weather fronts varying by seasons but similar across years, go through phases that become familiar if observers note historical patterns” (Cuban, 2011). Those with a few decades of public education under their belts have seen “reform” fronts blow through with every election cycle. During this study, a “perfect storm” hit and teachers were sent running for their umbrellas and boots. This particular cycle is remarkable because it comes on the heels of the collapse of the “No Child Left Behind” (NCLB) Act (U.S. Department of Education, 2001). States filed for U.S. Department of Education NCLB waivers because they could not meet the 100% pass rates on Annual Yearly Progress (AYP) by 2015. At the same time, 18 Race to the Top (RT3) states and those with NCLB waiv- ers—almost all states—were required to implement RT3 mandates (U.S. Department of Education, 2009) (Ravich, 2015). -

Cahiers De Littérature Orale, 75-76 | 2014 the Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page 2

Cahiers de littérature orale 75-76 | 2014 L'autre voix de la littérature The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page Garrison Keillor’s Radio Romance Flore Coulouma Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/clo/1884 DOI: 10.4000/clo.1884 ISSN: 2266-1816 Publisher INALCO Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2014 ISBN: 978-2-85831-222-1 ISSN: 0396-891X Electronic reference Flore Coulouma, “The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page”, Cahiers de littérature orale [Online], 75-76 | 2014, Online since 29 April 2015, connection on 02 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/clo/1884 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/clo.1884 This text was automatically generated on 2 July 2021. Cahiers de littérature orale est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale 4.0 International. The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page 1 The Soundscape of Oral Tradition on the Printed Page Garrison Keillor’s Radio Romance Flore Coulouma Introduction 1 American author and radio personality Garrison Keillor has been described as “a brilliant writer, monologist and sometime crooner” and “arguably the biggest star in the world of public radio” (Smith, 2012; Carter, 2011). He is also listed as a “storyteller” on the popular American blog The Moth, home of a non-profit cultural organization devoted to oral storytelling. Besides hosting his acclaimed radio program A Prairie Home Companion, Keillor has published novels, short-story collections and poetry, and contributes columns and stories to the New York Times, The New Yorker and National Geographic, among others. -

Prairie Home | Dean

Prairie Home | Dean Prairie Home THOMAS DEAN still love to listen to the “News from Lake Wobegon” I on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion ev- ery Saturday night. Mr. Keillor’s droll yet often sharp narratives of life in a small middle land town contin- ue to amuse and comfort me after all these years. Over those years, the phrase “prairie home” has resonated more deeply, more acutely in my imagination, my heart, Photo Courtesy of Thomas Dean maybe my soul. For two years in the late 1990s, I lived in the Thomas Dean is Senior Presidential Writer/ northern prairie region in Moorhead, Minnesota, the Red River of the North serving as the good fence with Editor at the University of Iowa with pri- our neighbor Fargo, North Dakota. Tucked in the mid- mary responsibilities in speechwriting, and dle of Moorhead, not six blocks from my house, was the he teaches interdisciplinary courses at the Prairie Home Cemetery, from which Mr. Keillor him- university as well. He also teaches with the self says he derived the name for his radio program after Iowa Summer Writing Festival and the UI a 1971 reading at Moorhead State University (the insti- First-Year Seminar Program. Dean received tution where I taught at the time I lived there). It’s an old a BA in English, a BM in Music History Norwegian graveyard, and in fact the house my fami- and Literature, and an MA in English from ly and I lived in in Moorhead was connected to one of Northern Illinois University, and a PhD in those buried there. -

Report MAY 2007

report MAY 2007 LONG GONE LAKE WOBEGON? The State of Investments in University of Minnesota Research PHILIP G. PARDEY, STEVEN DEHMER, AND JASON BEDDOW ABOUT THE TITLE The Lake Wobegon eff ect refers to the tendency for individuals (or groups) to overestimate their own abilities or achievements in relation to others (see, for example, Maxwell and Lopus 1994). It is named for the fi ctional town of Lake Wobegon from the radio series A Prairie Home Companion, where, according to University of Minnesota alumnus Garrison Keillor, “all the women are strong, the men are good looking, and all the children are above average.” The principal fi nding of this report is that while the University of Minnesota remains a strong public research university, it is no longer “above average” in a range of research funding metrics. Research expenditures at several competing institutions—primarily during the 1990s—have grown at a faster pace, placing the University, and the state of Minnesota, at a competitive disadvantage. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Philip Pardey is a professor in the Department of Applied Economics, University of Minnesota and directs the University's center for International Science and Technology Practice and Policy (InSTePP). Steven Dehmer and Jason Beddow are graduate students in the Department of Applied Economics, University of Minnesota. ABOUT INSTEPP The International Science and Technology Practice and Policy (InSTePP) center is located in the Department of Applied Economics at the University of Minnesota. InSTePP brings together a community of scholars at the University of Minnesota and elsewhere to engage in economic research on science and technology practice and policy, emphasizing the international implications.