Did the Evolutionary Transition of Aphids from Angiosperm to Non-Spermatophyte Vascular Plants Have Any Effect on Probing Behaviour?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California's Native Ferns

CALIFORNIA’S NATIVE FERNS A survey of our most common ferns and fern relatives Native ferns come in many sizes and live in many habitats • Besides living in shady woodlands and forests, ferns occur in ponds, by streams, in vernal pools, in rock outcrops, and even in desert mountains • Ferns are identified by producing fiddleheads, the new coiled up fronds, in spring, and • Spring from underground stems called rhizomes, and • Produce spores on the backside of fronds in spore sacs, arranged in clusters called sori (singular sorus) Although ferns belong to families just like other plants, the families are often difficult to identify • Families include the brake-fern family (Pteridaceae), the polypody family (Polypodiaceae), the wood fern family (Dryopteridaceae), the blechnum fern family (Blechnaceae), and several others • We’ll study ferns according to their habitat, starting with species that live in shaded places, then moving on to rock ferns, and finally water ferns Ferns from moist shade such as redwood forests are sometimes evergreen, but also often winter dormant. Here you see the evergreen sword fern Polystichum munitum Note that sword fern has once-divided fronds. Other features include swordlike pinnae and round sori Sword fern forms a handsome coarse ground cover under redwoods and other coastal conifers A sword fern relative, Dudley’s shield fern (Polystichum dudleyi) differs by having twice-divided pinnae. Details of the sori are similar to sword fern Deer fern, Blechnum spicant, is a smaller fern than sword fern, living in constantly moist habitats Deer fern is identified by having separate and different looking sterile fronds and fertile fronds as seen in the previous image. -

The Glycosyltransferase Repertoire of the Spikemoss Selaginella Moellendorffiind a a Comparative Study of Its Cell Wall

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Department of Botany and Plant Pathology Faculty Department of Botany and Plant Pathology Publications 5-2-2012 The Glycosyltransferase Repertoire of the Spikemoss Selaginella moellendorffiind a a Comparative Study of Its Cell Wall. Jesper Harholt Iben Sørensen Cornell University Jonatan Fangel Alison Roberts University of Rhode Island William G.T. Willats See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/btnypubs Recommended Citation Harholt, Jesper; Sørensen, Iben; Fangel, Jonatan; Roberts, Alison; Willats, William G.T.; Scheller, Henrik Vibe; Petersen, Bent Larsen; Banks, Jo Ann; and Ulvskov, Peter, "The Glycosyltransferase Repertoire of the Spikemoss Selaginella moellendorffii and a Comparative Study of Its Cell Wall." (2012). Department of Botany and Plant Pathology Faculty Publications. Paper 15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035846 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Authors Jesper Harholt, Iben Sørensen, Jonatan Fangel, Alison Roberts, William G.T. Willats, Henrik Vibe Scheller, Bent Larsen Petersen, Jo Ann Banks, and Peter Ulvskov This article is available at Purdue e-Pubs: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/btnypubs/15 The Glycosyltransferase Repertoire of the Spikemoss Selaginella moellendorffii and a Comparative Study of Its Cell Wall Jesper Harholt1, Iben Sørensen1,2, Jonatan Fangel1, Alison Roberts3, William G. -

Information and Care Instructions Mother Fern

Information and Care Instructions Mother Fern Quick Reference Botanical Name - Asplenium bulbiferum Detailed Care Exposure - Shade to bright, indirect Your Mother Fern was grown in a plastic pot. Depending on the item, it may then have been Indoor Placement - Bright location but not in direct afternoon sun transplanted into a decorative pot before sale or simply “dropped” into a container while still in the USDA Hardiness - Zone 10a to 11 plastic pot. Inside Temperature - 50-70˚F WATERING Min Outside Temperature - 30˚F 1. Let the top of the soil dry out slightly before Plant Type - Evergreen Fern watering; check frequently, especially if kept in a hot, dry spot. Mother Ferns like to be kept evenly moist, Watering - Allow soil to dry out slightly before watering. Do not allow but not soggy. the pot to sit in standing water for more than a few minutes 2. When watering, use the recommended amount of water for your pot size (See Quick Reference Guide) Water Amount Used - 4” Pot = 1/3 cup of water poured directly on the soil. In order not to damage 6 1/2” Pot = 1 1/4 cups of water your furniture, countertop or floor, place your Mother Fertilizing - Fertilize monthly Fern in a saucer, bowl or sink when watering. Allow the water to drain for 5 minutes. Do not allow the soil to sit in water for any more than 5 minutes or damage to the roots may occur. Avoid continuous use of softened water as the sodium in it can build up to damaging levels in the soil. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

Seedless Plants Key Concept Seedless Plants Do Not Produce Seeds 2 but Are Well Adapted for Reproduction and Survival

Seedless Plants Key Concept Seedless plants do not produce seeds 2 but are well adapted for reproduction and survival. What You Will Learn When you think of plants, you probably think of plants, • Nonvascular plants do not have such as trees and flowers, that make seeds. But two groups of specialized vascular tissues. plants don’t make seeds. The two groups of seedless plants are • Seedless vascular plants have specialized vascular tissues. nonvascular plants and seedless vascular plants. • Seedless plants reproduce sexually and asexually, but they need water Nonvascular Plants to reproduce. Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts do not have vascular • Seedless plants have two stages tissue to transport water and nutrients. Each cell of the plant in their life cycle. must get water from the environment or from a nearby cell. So, Why It Matters nonvascular plants usually live in places that are damp. Also, Seedless plants play many roles in nonvascular plants are small. They grow on soil, the bark of the environment, including helping to form soil and preventing erosion. trees, and rocks. Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts don’t have true stems, roots, or leaves. They do, however, have structures Vocabulary that carry out the activities of stems, roots, and leaves. • rhizoid • rhizome Mosses Large groups of mosses cover soil or rocks with a mat of Graphic Organizer In your Science tiny green plants. Mosses have leafy stalks and rhizoids. A Journal, create a Venn Diagram that rhizoid is a rootlike structure that holds nonvascular plants in compares vascular plants and nonvas- place. Rhizoids help the plants get water and nutrients. -

Evolution of Land Plants P

Chapter 4. The evolutionary classification of land plants The evolutionary classification of land plants Land plants evolved from a group of green algae, possibly as early as 500–600 million years ago. Their closest living relatives in the algal realm are a group of freshwater algae known as stoneworts or Charophyta. According to the fossil record, the charophytes' growth form has changed little since the divergence of lineages, so we know that early land plants evolved from a branched, filamentous alga dwelling in shallow fresh water, perhaps at the edge of seasonally-desiccating pools. The biggest challenge that early land plants had to face ca. 500 million years ago was surviving in dry, non-submerged environments. Algae extract nutrients and light from the water that surrounds them. Those few algae that anchor themselves to the bottom of the waterbody do so to prevent being carried away by currents, but do not extract resources from the underlying substrate. Nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, together with CO2 and sunlight, are all taken by the algae from the surrounding waters. Land plants, in contrast, must extract nutrients from the ground and capture CO2 and sunlight from the atmosphere. The first terrestrial plants were very similar to modern mosses and liverworts, in a group called Bryophytes (from Greek bryos=moss, and phyton=plants; hence “moss-like plants”). They possessed little root-like hairs called rhizoids, which collected nutrients from the ground. Like their algal ancestors, they could not withstand prolonged desiccation and restricted their life cycle to shaded, damp habitats, or, in some cases, evolved the ability to completely dry-out, putting their metabolism on hold and reviving when more water arrived, as in the modern “resurrection plants” (Selaginella). -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

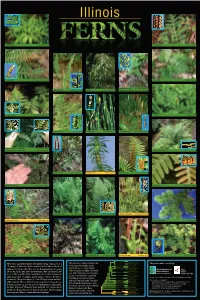

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Spermatophyte Flora of Liangzi Lake Wetland Nature Reserve

E3S Web of Conferences 143, 02040 (2 020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20 2014302040 ARFEE 2019 Spermatophyte Flora of Liangzi Lake Wetland Nature Reserve Xinyang Zhang, Shijing He*, Rong Tao, and Huan Dai Wuhan Institute of Design and Sciences, Wuhan 430205, China Abstract. Based on route and sample-plot survey, plant resources of Liangzi Lake Wetland Nature Reserve were investigated. The result showed that there were 503 species of spermatophyte belonging to 296 genera of 86 families. There were 5 species under national first and second level protection. The dominant families of spermatophyte contained 20 species and above. The dominant genera of spermatophyte contained 4 species and below. The 86 families of spermatophyte can be divided into 7 distribution types and 4 variants. Tropic distribution type was dominant, accounting for 70.83% in total (excluding cosmopolitans). The 296 genera of spermatophyte can be divided into 14 distribution types and 9 variants. Temperate elements were a little more than tropical elements, accounting for 50.84% and 49.16% in total (excluding cosmopolitans) respectively. Reserve had 3 Chinese endemic genera, reflecting certain ancient and relict. The purpose of the research is to provide background information and scientific basis for the protection, construction, management and rational utilization of plant resources in the reserve. 1 Preface temperature is 17℃, the annual average rainfall is 1663mm, the average sunshine hour is 2061 hours, and Flora refers to the sum of all plant species in a certain the frost free period is 270 days. The rain bearing area is region or country. It is the result of the development and 208500 hectares, and the annual average water level is evolution of the plant kingdom under certain natural and 17.81m. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0186-6546 Gar W. Rothwell Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of Environmental and Plant Biology Porter Hall 401E T: 740 593 1129 Ohio University F: 740 593 1130 Athens, OH 45701 E: [email protected] also Courtesy Professor Department of Botany and PlantPathology Oregon State University T: 541 737- 5252 Corvallis, OR 97331 E: [email protected] Education Ph.D.,1973 University of Alberta (Botany) M.S., 1969 University of Illinois, Chicago (Biology) B.A., 1966 Central Washington University (Biology) Academic Awards and Honors 2018 International Organisation of Palaeobotany lifetime Honorary Membership 2014 Fellow of the Paleontological Society 2009 Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America 2004 Ohio University Distinguished Professor 2002 Michael A. Cichan Award, Botanical Society of America 1999-2004 Ohio University Presidential Research Scholar in Biomedical and Life Sciences 1993 Edgar T. Wherry Award, Botanical Society of America 1991-1992 Outstanding Graduate Faculty Award, Ohio University 1982-1983 Chairman, Paleobotanical Section, Botanical Society of America 1972-1973 University of Alberta Dissertation Fellow 1971 Paleobotanical (Isabel Cookson) Award, Botanical Society of America Positions Held 2011-present Courtesy Professor of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University 2008-2009 Visiting Senior Researcher, University of Alberta 2004-present Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio -

Havens for Wildlife

)"7&/4'038*-%-*'& 4FDUJPO# .PTTFT -JWFSXPSUTBOE'FSOT This sheet explains what mosses, liverworts and Liverworts ferns are, where they occur and guidelines on how Liverworts are similar to to care for them in a burial ground. mosses but tend to be The earliest land plants were related to ferns and leafy and are less common. mosses. They started life growing on the edge of lakes Liverworts are mostly found and rivers 400 million years ago. Today most ferns, in woodland and by streams mosses and liverworts still need to grow in moist or rivers but can also be found places. on shady stones and damp soil in burial grounds. They are With our damp climate many burial sites prove ideal for strange, distinctive looking ferns, mosses and liverworts, particularly in the western plants and worth looking at areas of Britain and Ireland. closely or photographing their Adder’s-tongue Fern intricate shapes and subtle colours. MOSSES AND LIVERWORTS Mosses and liverworts are known as FERNS ‘bryophytes’. They are small, green plants *OUIFDPPM XFUDMJNBUFPGUIF6,UIFSFBSFUZQFTPG which do not have !owers or seeds but fern. Look out for ferns on west or north facing walls produce spores instead. There are over in particular. The shady areas of burial grounds, and 1000 di"erent species of bryophyte in under trees, where grass cutters don’t reach, will also UIF6,BOEUIFZUFOEUPCFGPVOEJO be places where ferns can !ourish undisturbed. sheltered, damp places as most of them cannot survive drying out. Few mosses An amazing fact about ferns is that once established PSMJWFSXPSUTIBWF&OHMJTIOBNFTBOEB they can survive in quite dry places, such as walls. -

Diversity and Evolution of the Megaphyll in Euphyllophytes

G Model PALEVO-665; No. of Pages 16 ARTICLE IN PRESS C. R. Palevol xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Comptes Rendus Palevol w ww.sciencedirect.com General palaeontology, systematics and evolution (Palaeobotany) Diversity and evolution of the megaphyll in Euphyllophytes: Phylogenetic hypotheses and the problem of foliar organ definition Diversité et évolution de la mégaphylle chez les Euphyllophytes : hypothèses phylogénétiques et le problème de la définition de l’organe foliaire ∗ Adèle Corvez , Véronique Barriel , Jean-Yves Dubuisson UMR 7207 CNRS-MNHN-UPMC, centre de recherches en paléobiodiversité et paléoenvironnements, 57, rue Cuvier, CP 48, 75005 Paris, France a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Recent paleobotanical studies suggest that megaphylls evolved several times in land plant st Received 1 February 2012 evolution, implying that behind the single word “megaphyll” are hidden very differ- Accepted after revision 23 May 2012 ent notions and concepts. We therefore review current knowledge about diverse foliar Available online xxx organs and related characters observed in fossil and living plants, using one phylogenetic hypothesis to infer their origins and evolution. Four foliar organs and one lateral axis are Presented by Philippe Taquet described in detail and differ by the different combination of four main characters: lateral organ symmetry, abdaxity, planation and webbing. Phylogenetic analyses show that the Keywords: “true” megaphyll appeared at least twice in Euphyllophytes, and that the history of the Euphyllophytes Megaphyll four main characters is different in each case. The current definition of the megaphyll is questioned; we propose a clear and accurate terminology in order to remove ambiguities Bilateral symmetry Abdaxity of the current vocabulary. -

Late Devonian Spermatophyte Diversity and Paleoecology at Red Hill, North-Central Pennsylvania, U.S.A. Walter L

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Geology & Astronomy Faculty Publications Geology & Astronomy 2010 Late Devonian spermatophyte diversity and paleoecology at Red Hill, north-central Pennsylvania, U.S.A. Walter L. Cressler III West Chester University, [email protected] Cyrille Prestianni Ben A. LePage Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/geol_facpub Part of the Geology Commons, Paleobiology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Cressler III, W.L., Prestianni, C., and LePage, B.A. 2010. Late Devonian spermatophyte diversity and paleoecology at Red Hill, north- central Pennsylvania, U.S.A. International Journal of Coal Geology 83, 91-102. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Geology & Astronomy at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geology & Astronomy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE IN PRESS COGEL-01655; No of Pages 12 International Journal of Coal Geology xxx (2009) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Coal Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijcoalgeo Late Devonian spermatophyte diversity and paleoecology at Red Hill, north-central Pennsylvania, USA Walter L. Cressler III a,⁎, Cyrille Prestianni b, Ben A. LePage c a Francis Harvey Green Library, 29 West Rosedale Avenue, West Chester University, West Chester, PA, 19383, USA b Université de Liège, Boulevard du Rectorat B18, Liège 4000 Belgium c The Academy of Natural Sciences, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA, 19103 and PECO Energy Company, 2301 Market Avenue, S9-1, Philadelphia, PA 19103, USA article info abstract Article history: Early spermatophytes have been discovered at Red Hill, a Late Devonian (Famennian) fossil locality in north- Received 9 January 2009 central Pennsylvania, USA.