An Aramaic Inscription from Daskyleion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

THE CHURCHES of GALATIA. PROFESSOR WM RAMSAY's Very

THE CHURCHES OF GALATIA. NOTES ON A REGENT CONTROVERSY. PROFESSOR W. M. RAMSAY'S very interesting and impor tant work on The Church in the Roman Empire has thrown much new light upon the record of St. Paul's missionary journeys in Asia Minor, and has revived a question which of late years had seemingly been set at rest for English students by the late Bishop Lightfoot's Essay on "The Churches of Galatia" in the Introduction to his Commen tary on the Epistle to the Galatians. The question, as there stated (p. 17), is whether the Churches mentioned in Galatians i. 2 are to be placed in "the comparatively small district occupied by the Gauls, Galatia properly so called, or the much larger territory in cluded in the Roman province of that name." Dr. Lightfoot, with admirable fairness, first points out in a very striking passage some of the " considerations in favour of the Roman province." " The term 'Galatia,' " he says, " in that case will comprise not only the towns of Derbe and Lystra, but also, it would seem, !conium and the Pisidian Antioch; and we shall then have in the narrative of St. Luke (Acts xiii. 14-xiv. 24) a full and detailed account of the founding of the Galatian Churches." " It must be confessed, too, that this view has much to recom mend it at first sight. The Apostle's account of his hearty and enthusiastic welcome by the Galatians as an angel of God (iv. 14), would have its counterpart in the impulsive warmth of the barbarians at Lystra, who would have sacri ficed to him, imagining that 'the gods had come down in VOL. -

The Call to Macedonia

THE CALL TO MACEDONIA (ACTS 16:6-10) MEMORY VERSE: " 'Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.' Amen." MATTHEW 28:19-20 CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORD: 1. "Now when they had gone through Phrygia and the region of Galatia, they were (FORBIDDEN, LED) by the Holy Spirit to preach the word in Asia." ACTS 16:6 TRUE OR FALSE: 2. "After they had come to Mysia, they tried to go into Bithynia, but the Spirit did not permit them." ACTS 16:7 TRUE OR FALSE 3. So stopping in Mysia, they rested. ACTS 16:8 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORD: 4. "And a (STAR, VISION) appeared to Paul in the night..." ACTS 16:9 TRUE OR FALSE: 5. "...A man of Macedonia stood and pleaded with him, saying, 'Come over to Macedonia and help us.' " ACTS 16:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORD: 6. "Now after he had seen the vision, immediately we sought to go to Macedonia, concluding that the (MAN, LORD) had called us to preach the gospel to them." ACTS 16:10 1/2 THE CALL TO MACEDONIA (ACTS 16:6-10) MEMORY VERSE: " 'Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.' Amen." MATTHEW 28:19-20 FILL IN THE BLANK: 1. -

Review Article UPON the BORDERS of MACEDONIA SECUNDA

Irena Teodora VESEVSKA UDK: 908(497.7)”652” Review article UPON THE BORDERS OF MACEDONIA SECUNDA – FACTS, ASSUMPTIONS, CONSIDERATIONS Abstract The borders of the Roman Empire, which fluctuated throughout the empire's history, were a combination of natural frontiers and man-made fortifications which separated the lands of the empire from the ”barbarian” lands beyond. In assessing the territory of the Roman Empire, we can observe different geographical and artifi- cial administrative demarcations. At the outskirts we have the frontiers that deter- mined the physical edges of the empire, which established not only the Empire’s size geographically, but also designated the limits of the territory that was to be ruled by the Empire’s administration. The expansion of the empire in the Late Republic and (early) Empire led to an increase of provincial territories and thus of provincial bo- undaries or borders, separating the different provincial territories from each other. The sources of the topography of Macedonia in the Roman period are very poor despite the many geographical and historical works that treat its territory. For the gradual alteration and redefinition of administrative boundaries, the creation of new and the abolition of the old provinces, the sources offer a fragmented picture, while offering only partial details on the definition of the boundaries. In this regard, the attempt to define the exact boundaries between the late antique provinces is ba- sed on several reliable facts and many assumptions. Keywords: LATE ANTIQUE, ROMAN PROVINCES, ADMINISTRATION, MACEDONIA, BORDERS Introduction The bureaucratic system of the Roman Empire, composed with the most serious attention to detail, as a solution to the serious problem of main- taining a vast heterogeneous empire, endangered by dissolution and bank- ruptcy, far from being geographically compact, with its four long, as well as several smaller defending borderlines, was one of the key links for control- ling and governing the spacious territory. -

'Temple States' of Pontus: Comana Pontica and Zela A

‘TEMPLE STATES’ OF PONTUS: COMANA PONTICA AND ZELA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY EM İNE SÖKMEN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY APRIL 2005 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Numan Tuna Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Asist. Prof. Dr .Deniz Burcu Erciyas Supervisor Examining Committee Members (first name belongs to the chairperson of the jury and the second name belongs to supervisor) Prof. Dr. Suna Güven (METU,AH) Asist. Prof. Dr. Deniz Burcu Erciyas (METU, SA) Asist. Prof. Dr. Jan Krzysztof Bertram (METU, SA) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Emine Sökmen Signature : iii ABSTRACT ‘TEMPLE STATES’ OF PONTUS: COMANA PONTICA AND ZELA Sökmen, Emine M.S., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Asist. Prof. Dr. Deniz Burcu Erciyas April 2005, 68 pages Before the Roman rule in Asia Minor, under the Hellenistic kings, small communities lived independently within areas surrounding temples with local powers. -

III. Second Missionary Journey AD 48-51 B. Galatia and Mysia Acts 16:1-10

III. Second Missionary Journey AD 48-51 B. Galatia and Mysia Acts 16:1-10. 1 Tim. 4:14 1 Paul went on also to Derbe and to Lystra, Do not neglect the where there was a disciple named Timothy, the gift that is in you, which son of a Jewish woman who was a believer; but was given to you through his father was a Greek. 2 He was well spoken prophecy with the laying of by the believers in Lystra and Iconium. 3 Paul on of hands by the council wanted Timothy to accompany him; and he took of elders. him and had him circumcised because of the Jews who were in those places, for they all knew 2 Tim. 1:5-7 that his father was a Greek. 4 As they went from 5 I am reminded of town to town, they delivered to them for obser- your sincere faith, a faith vance the decisions that had been reached by that lived first in your the apostles and elders who were in Jerusalem. grandmother Lois and 5 So the churches were strengthened in the faith your mother Eunice and and increased in numbers daily. 6 They went now, I am sure, lives in through the region of Phrygia and Galatia, hav- you. 6 For this reason I ing been forbidden by the Holy Spirit to speak remind you to rekindle the the word in Asia. 7 When they had come oppo- gift of God that is within site Mysia, they attempted to go into Bithynia, you through the laying on but the Spirit of Jesus did not allow them; 8 so, of my hands; 7 for God did passing by Mysia, they went down to Troas. -

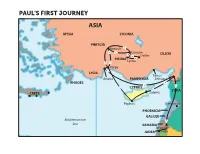

Paul's First Journey

PAUL’S FIRST JOURNEY ASIA MYSIA LYCONIA PHRYGIA Antioch Iconium CILICIA Derbe PISIDIA Lystra Perga LYCIA Tarsus Attalia PAMPHYLIA Seleucia Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Salamis Paphos Damascus PHOENICIA GALILEE Mediterranean Sea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA Gaza PAUL’S SECOND JOURNEY Neapolis Philippi BITHYNIA Amphipolis MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Troas ASIA GALATIA GREECE Aegean MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Sea PHRYGIA Athens Corinth Ephesus Iconium Cenchreae Trogylliun PISIDIA Derbe CILICIA Lystra LYCIA PAMPHYLIA Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Paphos PHOENICIA Mediterranean Sea GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara RHODES Antioch CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S JOURNEY TO ROME DALMATIA Black Sea Adraitic THRACE ITALY Sea ROME MACEDONIA Three Taverns PONTUS Appii Forum Pompeii BITHYNIA Puteoli ASIA GREECE Agean Sea Tyrrhenian MYSIA Sea ACHAIA PHRYGIA CAPPADOCIA GALATIA LYCAONIA Ionian Sea PISIDIA SICILY Rhegium CILICIA Syracuse LYCIA PAMPHYLIA CRETE Myca RHODES MALTA SYRIA (MELITA) Clauda Fort CYPRUS Havens Mediterranean Sea PHOENICIA GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Antipatris CYRENAICA Jerusalem TRIPOLITANIA LIBYA JUDEA EGYPT. -

Researches in Lydia, Mysia and Aiolis

© 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by libraries associated to dandelon.com network. OSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORLSCHE K LASSE DENKSCHRIFTEN, 279. BAND ERGANZUNGSBANDE ZU DEN TTTULI ASIAE MINORIS NR. 23 HASAN MALAY RESEARCHES IN LYDIA, MYSIA AND AIOLIS WITH 246 FIGURES AND A MAP VERLAG DER OSTERREICHISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN WIEN 1999 CONTENTS Vorwort des Herausgebers 13 Preface 15 Abbreviations 17 I AIGAI 1 Boundary Inscription of Aigai (Aeolic) 21 2 Funerary Inscription for Aristodike (Aeolic) 22 3 Boundary Stone of a Land Dedicated to Apollon Chresterios by the King Eumenes I 22 4 Fragment of a Funerary Inscription 23 II STRATONIKEIA - HADRIANOPOLIS 5 EphebicList 25 6 Funerary Inscription for Gaios 26 7 Funerary Inscription for Anenkliane (?) 26 8 Funerary Inscription 27 9 Funerary Inscription for Paulinas 28 10 Fragment of a Funerary Inscription 28 11 Fragment of a Funerary Inscription 28 12 Funerary Inscription for Demarchos and his Family 29 13 Funerary Inscription for Papias 29 III NAKRASON (or NAKRASOS) 14 Honour to Hadrianus by the Nakrasitai 31 15 Funerary Inscription for Ammion (?), Daughter of Menis 32 IV THYATEIRA 16 Ephebic List 33 17 Record Concerning the Domus Augusta or a Building Used for the Imperial Cult.... 34 18 Honour to Titus 35 19 Honour to an Agonothet 36 20 Honour to C. Perelius Alexander by Gnapheis 37 21 Honour to L. Vedius Capito Glabrionianus, a Curator (Rei Publicae ?) 38 22 Honour to C. Valerius Menogenes Annianus 38 23 Fragment of a Building-Inscription 40 24 Dedication of a Stoa 40 25 Dedication to Apollon Tyrimnos 42 26 Dedication to Theos Hypsistos by Ioulianos, a Dyer 42 27 Dedication to Theos Hypsistos 42 28 Funerary Inscription for Menandros Pyros 43 29 Dedication to Hestia 43 6 H. -

The Jews in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt

Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Peter Schäfer 7 The Jews in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt The Struggle for Equal Rights by Aryeh Kasher J. C. B. Möhr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen Revised and translated from the Hebrew original: rponm fl'taDij'jnn DnSQ HliT DDTlinsT 'jp Dpanaa (= Publications of the Diaspora Research Institute and the Haim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies, edited by Shlomo Simonsohn, Book 23). Tel Aviv University 1978. CIP-Kurztitelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek Kasher, Aryeh: The Jews in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt: the struggle for equal rights / Aryeh Kasher. - Tübingen: Mohr, 1985. (Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum; 7) ISBN 3-16-144829-4 NE: GT First Hebrew edition 1978 Revised English edition 1985 © J. C. B. Möhr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen 1985. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. / All rights reserved. Printed in Germany. Säurefreies Papier von Scheufeien, Lenningen. Typeset: Sam Boyd Enterprise, Singapore. Offsetdruck: Guide-Druck GmbH, Tübingen. Einband: Heinr. Koch, Tübingen. In memory of my parents Maniya and Joseph Kasher Preface The Jewish Diaspora has been part and parcel of Jewish history since its earliest days. The desire of the Jews to maintain their na- tional and religious identity, when scattered among the nations, finds its actual expression in self organization, which has served to a ram- part against external influence. The dispersion of the people in modern times has become one of its unique characteristics. Things were different in classical period, and especially in the Hellenistic period, following the conquests of Alexander the Great, when disper- sion and segregational organization were by no means an exceptional phenomenon, as revealed by a close examination of the history of other nations. -

Popular and Imperial Response to Earthquakes in the Roman Empire

Popular and Imperial Response to Earthquakes in the Roman Empire A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Christopher M. Higgins June 2009 © 2009 Christopher M. Higgins. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Popular and Imperial Response to Earthquakes in the Roman Empire by CHRISTOPHER M. HIGGINS has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Jaclyn Maxwell Associate Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT HIGGINS,CHRISTOPHER M., M.A., June 2009, History Popular and Imperial Response to Earthquakes in the Roman Empire (120 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jaclyn Maxwell This thesis examines popular and imperial response to earthquakes in the Roman Empire period from the reign of Augustus through the reign of Justinian. It examines religious and scientific attitudes towards earthquakes throughout the classical period and whether these attitudes affected the disaster relief offered by Roman emperors. By surveying popular and imperial reactions throughout the time period this thesis shows that Roman subjects reacted in nearly identical manners regardless of the official religion of the Empire. The emperors followed a precedent set by Augustus who was providing typical voluntary euergetism. Their responses showcased imperial philanthropy while symbolizing the power and presence of the Roman state even in far off provinces. The paper also examines archaeological evidence from Sardis and Pompeii each of whose unique archaeological circumstances allows for an illustration of methods of reconstruction following earthquakes of massive and moderate size. -

̱ Ͷͷͷ ̱ Ancient and Current Toponomy of Asia Minor

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 4 No.4 ISSN 2240-0524 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy June 2014 Ancient and Current Toponomy of Asia Minor Asst. Prof. Dr. Mustafa Arslan Selcuk University Beyúehir Ali Akkanat Faculty of Tourism [email protected] Doi:10.5901/jesr.2014.v4n4p455 Abstract Strabo, the geographer, was born (64/63-23? AD) in Amesia in Asia Minor. Today Amasia is called as Amasya in Anatolia. His book, the Geography, is an important ancient source for the toponomy of Anatolia. He described some parts of Asia Minor in his books XII to XIV. Historical conditions have changed since he wrote his book. As Anatolia is a very important peninsula like a cultural bridge between Europe and Asia, many ethnic groups of people have settled here or affected the culture of the region. At least Strabo’s Asia Minor has become Anatolia or Anadolu in Turkish. In addition to these, thousands of settlements were renamed in 1950 and 1960s. The programme for renaming the settlements also changed original Turkish names. Despite of all the changes in the history and the toponomy of Asia Minor-Anatolia, names of some settlements have survived and are still in use with little or no change in sound. In this paper, the toponomy of Strabo’s work and the toponomy of current Anatolia are compared and the unchanged or little changed place names are studied. Keywords: Asia Minor, Anatolia, Ancient Geography, Place Names. 1. Introduction Strabo the geographer was a native of Anatolia and a Greek citizen from Amasia in Pontus region.