Members of Parliament Are Minimally Accountable for Their Issue Stances (And They Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Report Monday, 4 February 2019 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 4 February 2019 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 4 February 2019 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:00 P.M., 04 February 2019). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Cabinet Office: Written ATTORNEY GENERAL 7 Questions 13 Attorney General: Trade Census: Sikhs 13 Associations 7 Cybercrime 14 Crown Prosecution Service: Cybercrime: EU Countries 14 Staff 7 Interserve 14 Crown Prosecution Service: Interserve: Living Wage 15 West Midlands 7 Reducing Regulation Road Traffic Offences: Committee 15 Prosecutions 8 DEFENCE 15 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 9 Arctic: Defence 15 Climate Change Convention 9 Armed Forces: Doctors 15 Companies: National Security 9 Armed Forces: Professional Organisations 16 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: Army: Deployment 16 Brexit 10 Army: Officers 16 Energy: Subsidies 10 Chinook Helicopters: Innovation and Science 11 Accidents 17 Insolvency 11 Ecuador: Military Aid 17 Iron and Steel 12 European Fighter Aircraft: Safety Measures 17 Telecommunications: National Security 12 General Electric: Rugby 18 CABINET OFFICE 13 HMS Mersey: English Channel 18 Cabinet Office: Trade Joint Strike Fighter Aircraft: Associations 13 Safety Measures 18 Ministry of Defence: Brexit 19 Ministry of Defence: Public Free School Meals: Newcastle Expenditure 19 Upon Tyne Central 36 Royal Tank -

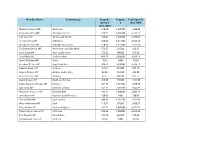

London Manchester Number of Employees by Parliamentary

Constituency MP Employees Constituency MP Employees Aberconwy Guto Bebb 4 KDC Contractors Ltd 8 Matom Limited 4 Kier Construction Limited 50 Dounreay Aberdeen North Kirsty Blackman 3 Matom Limited 9 Thurso, Caithness MMI Engineering Ltd 2 Mott MacDonald Ltd 2 dounreay.com SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 1 URENCO 450 Bury North Salford Aberdeen South Ross Thomson 4 URENCO Nuclear Stewardship & Eccles 80 PBO: Cavendish Dounreay Partnership Ltd Manchester AECOM 2 Coatbridge, Chryston and Bellshill Hugh Gaffney 27 (Cavendish Nuclear, CH2M, AECOM) Worsley & Nuvia 2 Scottish Enterprise 1 Lifetime: 1955–1994 Eccles South Airdrie and Shotts Neil Gray 68 SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 26 Operation: Development of prototype Balfour Beatty 22 Copeland Trudy Harrison 13,045 fast breeder reactors BRC Reinforcement Ltd 41 AECOM 11 People: More than 1,000 Bolton West Morgan Sindall Infrastructure 5 ARUP 46 Aldershot Leo Docherty 69 Assystem UK Ltd 27 Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross Wigan Fluor Corporation 12 Balfour Beatty 151 Mirion Technologies (IST) Limited 56 Bechtel 17 NuScale Power 1 Bureau Veritas UK Ltd 71 Aldridge-Brownhills Wendy Norton 19 Capita Group 432 Stainless Metalcraft (Chatteris) Ltd 19 Capula Ltd 10 Maker eld Altrincham and Sale West Sir Graham Brady 108 Cavendish Nuclear Ltd 214 Manchester Mott MacDonald Ltd Costain The UK Civil Nuclear Industry Central 108 14 Alyn and Deeside Rt Hon Mark Tami 31 Direct Rail Services 18 James Fisher Nuclear Ltd 31 Doosan Babcock Limited 57 Argyll and Bute Brendan O’Hara 13 Gleeds 30 Denton Mott MacDonald Ltd 13 GRAHAM -

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary Debates

Monday Volume 652 7 January 2019 No. 228 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

The IR35 MP Hit List the 100 Politicians Most Likely to Lose Their Seats

The UK's leading contractor site. 200,000 monthly unique visitors. GUIDES IR35 CALCULATORS BUSINESS INSURANCE BANKING ACCOUNTANTS INSURANCE MORTGAGES PENSIONS RESOURCES FREE IR35 TEST The IR35 MP hit list The 100 politicians most likely to lose their seats Last December research conducted by ContractorCalculator identified the MPs for whom it will prove most costly to lose the selfemployed vote, and published the top 20 from each party. The results were based on data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and contractor sentiment indicated by a previous ContractorCalculator survey. The full results of this research are now published, with the top 100 MPs, ordered by risk of losing their seat, due to the Offpayroll (IR35) reforms that Treasury, HMRC and the Chancellor are attempting to push through Parliament. In total, 85 MPs hold a majority in Parliament that would feasibly be overturned if the expected turnout of IR35opposing selfemployed voters from their constituency were to vote against them, and we list the next 15, making 100 in total, that are potentially under threat if the self employed voter turnout is higher than expected. "This single piece of damaging policy could prove catastrophic for all parties involved, not least the Tories, who make up 43% of the atrisk seats,” comments ContractorCalculator CEO, Dave Chaplin. “There is also potentially a lot to gain for some, but those in precarious positions will have to act swiftly and earnestly to win over contractors’ trust.” How we identified the atrisk MPs The research leveraged the data and compared the MPs majority at the last election with the likely number of selfemployed voters in their area who would turn out and vote against them. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Membership on the 28Th February 2019

Membership on the 28th February 2019 was: Parliamentarians Philip Hollobone MP House of Commons John Howell MP Nigel Adams MP The Rt Hon Sir Lindsay Hoyle MP Adam Afriyie MP Stephen Kerr MP Peter Aldous MP Peter Kyle MP The Rt Hon Kevin Barron MP Chris Leslie MP Margaret Beckett MP Ian Lavery MP Luciana Berger MP Andrea Leadsom MP Clive Betts MP Dr Phillip Lee MP Roberta Blackman-Woods MP Jeremy Lefroy MP Alan Brown MP Brandon Lewis MP Gregory Campbell MP Clive Lewis MP Ronnie Campbell MP Ian Liddell-Grainger MP Sir Christopher Chope MP Ian Lucas MP The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP Rachel Maclean MP Colin Clark MP Khalid Mahmood MP Dr Therese Coffey MP John McNally MP Stephen Crabb MP Mark Menzies MP Jon Cruddas MP David Morris MP Martyn Day MP Albert Owen MP David Drew MP Neil Parish MP James Duddridge MP Mark Pawsey MP David Duguid MP John Penrose MP Angela Eagle MP Chris Pincher MP Clive Efford MP Rebecca Pow MP Julie Elliott MP Christina Rees MP Paul Farrelly MP Antoinette Sandbach MP Caroline Flint MP Tommy Sheppard MP Vicky Ford MP Mark Spencer MP George Freeman MP Mark Tami MP Mark Garnier MP Jon Trickett MP Claire Gibson Anna Turley MP Robert Goodwill MP Derek Twigg MP Richard Graham MP Martin Vickers MP John Grogan MP Tom Watson MP Trudy Harrison MP Matt Western MP Sue Hayman MP Dr Alan Whitehead MP James Heappey MP Sammy Wilson MP Drew Hendry MP European Parliament Stephen Hepburn MP Linda McAvan MEP William Hobhouse Dr Charles Tannock MEP Wera Hobhouse MP Wera Hobhouse MP Parliamentarians Lord Stoddart of Swindon House of Lords The Lord Teverson Lord Berkeley Lord Truscott The Lord Best OBE DL Lord Turnbull Lord Boswell The Rt Hon. -

Of Those Who Pledged, 43 Were Elected As

First name Last name Full name Constituency Party Rosena Allin-Khan Rosena Allin-Khan Tooting Labour Fleur Anderson Fleur Anderson Putney Labour Tonia Antoniazzi Tonia Antoniazzi Gower Labour Ben Bradshaw Ben Bradshaw Exeter Labour Graham Brady Graham Brady Altrincham and Sale West Conservative Nicholas Brown Nicholas Brown Newcastle upon Tyne East Labour Wendy Chamberlain Wendy Chamberlain North East Fife Lib Dem Angela Crawley Angela Crawley Lanark and Hamilton East SNP Edward Davey Edward Davey Kingston and Surbiton Lib Dem Florence Eshalomi Florence Eshalomi Vauxhall Labour Tim Farron Tim Farron Westmorland and Lonsdale Lib Dem Simon Fell Simon Fell Barrow and Furness Conservative Yvonne Fovargue Yvonne Fovargue Makerfield Labour Mary Foy Mary Foy City Of Durham Labour Kate Green Kate Green Stretford and Urmston Labour Fabian Hamilton Fabian Hamilton Leeds North East Labour Helen Hayes Helen Hayes Dulwich and West Norwood Labour Dan Jarvis Dan Jarvis Barnsley Central Labour Clive Lewis Clive Lewis Norwich South Labour Caroline Lucas Caroline Lucas Brighton, Pavilion Green Justin Madders Justin Madders Ellesmere Port and Neston Labour Kerry McCarthy Kerry McCarthy Bristol East Labour Layla Moran Layla Moran Oxford West and Abingdon Lib Dem Penny Mordaunt Penny Mordaunt Portsmouth North Conservative Jessica Morden Jessica Morden Newport East Labour Stephen Morgan Stephen Morgan Portsmouth South Labour Ian Murray Ian Murray Edinburgh South Labour Yasmin Qureshi Yasmin Qureshi Bolton South East Labour Jonathan Reynolds Jonathan Reynolds -

Formal Minutes 2017-19 1

Education Committee: Formal Minutes 2017-19 1 House of Commons Education Committee Formal Minutes of the Committee Session 2017–19 Education Committee: Formal Minutes 2017-19 2 Tuesday 12 September 2017 Members present: Robert Halfon, in the Chair Lucy Allan Trudy Harrison Michelle Donelan Ian Mearns Marion Fellows Lucy Powell James Frith William Wragg Emma Hardy 1. Declaration of interests Members declared their interests, in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 (see Appendix 1). 2. Working methods The Committee considered this matter. Ordered, That the Committee examine witnesses in public, except where it otherwise orders. Resolved, That witnesses who submit written evidence to the Committee are authorised to publish it on their own account in accordance with Standing Order No. 135, subject always to the discretion of the Chair or where the Committee otherwise orders. Resolved, That the Committee shall not consider individual cases. 3. Future programme The Committee considered this matter. Resolved, That the Committee take oral evidence from the Department for Education and its associated public bodies. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into fostering. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into alternative provision. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into value for money in higher education. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into the quality of apprenticeships and skills training. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into the integrity of public examinations. [Adjourned till 10 October 2017 at 9.30 am Education Committee: Formal Minutes 2017-19 3 Tuesday 10 October 2017 Members present: Robert Halfon, in the Chair Michelle Donelan Trudy Harrison Marion Fellows Ian Mearns James Frith Lucy Powell Emma Hardy William Wragg 1. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Daily Report Monday, 8 April 2019 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 8 April 2019 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 8 April 2019 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:37 P.M., 08 April 2019). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Lambeth Conference 16 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Pregnancy 16 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 7 Voting Behaviour 17 Automation 7 DEFENCE 17 Business: North West 8 Bomb Disposal: Northern Consumer Goods: Electrical Ireland 17 Safety 9 Firing Ranges 18 Consumers: Protection 10 Navy: Military Bases 19 Electricity: Storage 10 Royal Fleet Auxiliary: Energy: Government Procurement 19 Assistance 10 Saudi Arabia: European Engineering: Construction 11 Fighter Aircraft 19 Fracking 11 Saudi Arabia: Military Aid 20 Furniture and Furnishings Singapore: Navy 20 (Fire) (Safety) Regulations Type 31 Frigates: 1988 12 Procurement 20 Living Wage: Moray 12 Uganda: Military Aid 21 Motor Vehicles: Exhaust Yemen: Overseas Workers 21 Emissions 13 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND Music: Licensing 13 SPORT 21 Offshore Industry 13 Advertising: Statistics 21 Self-employed 14 Art Works 22 Third Energy 14 Cricket: Females 22 CHURCH COMMISSIONERS 15 Gaming Machines 23 Church Services: Attendance 15 Internet 23 Loneliness: Young People 24 ENVIRONMENT, FOOD AND Mobile Phones: Fees and RURAL AFFAIRS 39 Charges 25 Air Pollution: Nottinghamshire 39 EDUCATION 25 Air Pollution: Nurseries and Academies 25 Schools 40 Adult Education: -

Page 01 Feb 25.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com Special Lease Offer MEDINAMEDINA CENTRALECENTRALE Special Lease Offer PORTOPORTO ARABIAARABIA BUSINESS | 19 SPORT | 23 4409 5155 4409 5155 RBS net loss Alonso upbeat widens to over 'aggressive' £7bn new McLaren Saturday 25 February 2017 | 28 Jumada I 1438 Volume 21 | Number 7083 | 2 Riyals Katara opens new fountain Qatar supports UN Khalifa Stadium likely counter-terrorism efforts: Envoy to open by mid-2017 New York QNA Sanaullah Ataullah sport event its tourism sector QATAR'S permanent repre- The Peninsula witnessed remarkable boom. sentative to the United “We expect about a million Nations Ambassador Sheikha he Khalifa Interna- or a million-and-a-half visitors Alia Ahmed bin Saif Al Thani tional Stadium (KIS) and spectators during Qatar said that the country remains that is being redevel- 2022 which is more than visi- committed to all the UN's oped to host FIFA tors hosted by other countries counter-terrorism efforts. Wold Cup 2022 is in the past. The previous host The Ambassador praised Texpected to open by the end of countries of Fifa World-Cup the working plans of national second quarter of this year. received about 500,000 to and regional entities con- “We are moving as per our 600,000 visitors,” cerned with counter-terrorism schedule to complete all projects Khalifa International But Qatar’s geographical and preventing extremism. related to the World Cup 2022 Stadium will be location and its other factors like She said that violent extrem- on time, said Nasser Al Khater, opened by the end of having Qatar Airways and sup- ism is one of the biggest Assistant Secretary- General of second quarter of this ported by other regional airlines security challenges facing the the Supreme Committee for like Emirates will help to attract world. -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh