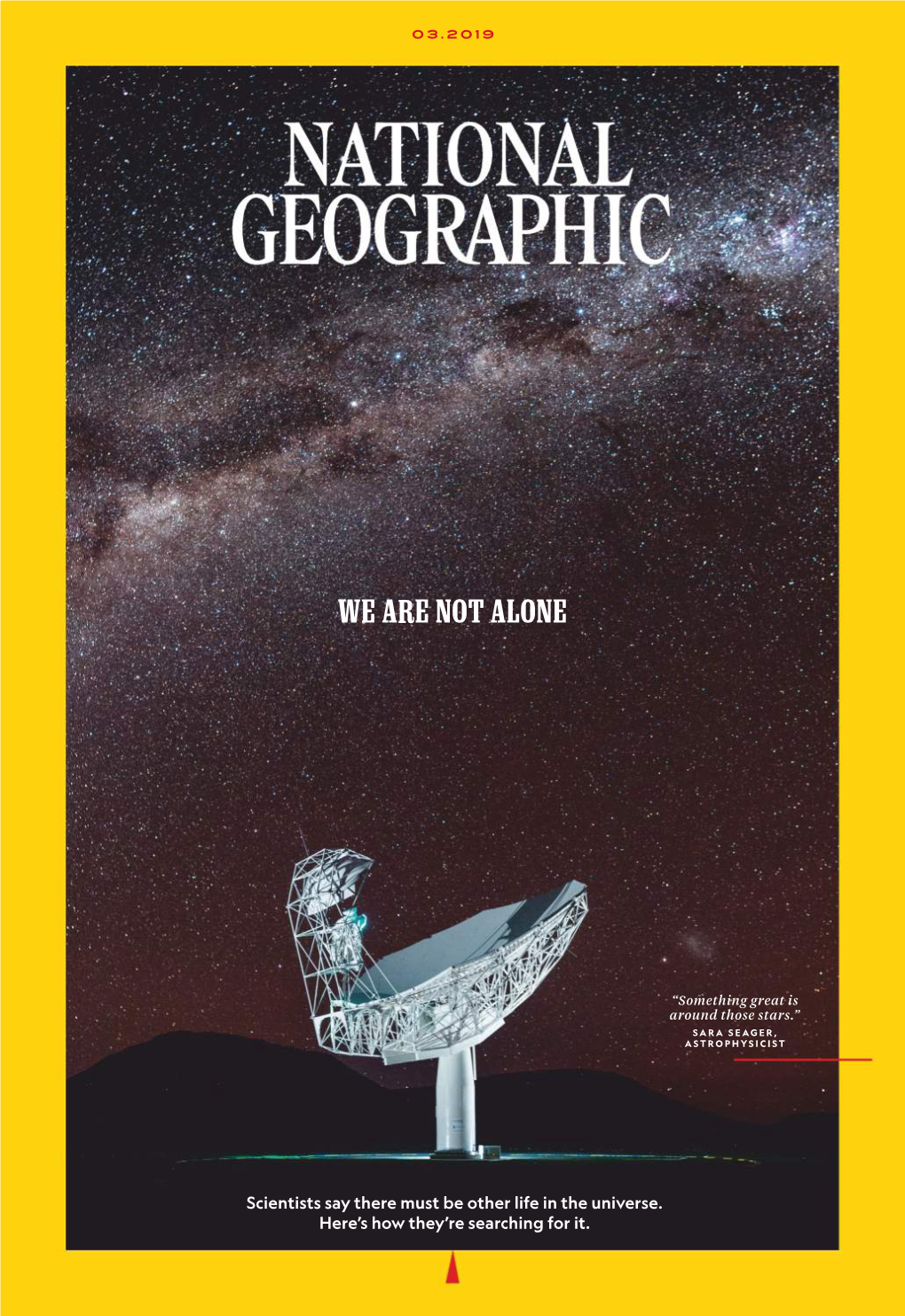

We Are Not Alone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstracts Connecting to the Boston University Network

20th Cambridge Workshop: Cool Stars, Stellar Systems, and the Sun July 29 - Aug 3, 2018 Boston / Cambridge, USA Abstracts Connecting to the Boston University Network 1. Select network ”BU Guest (unencrypted)” 2. Once connected, open a web browser and try to navigate to a website. You should be redirected to https://safeconnect.bu.edu:9443 for registration. If the page does not automatically redirect, go to bu.edu to be brought to the login page. 3. Enter the login information: Guest Username: CoolStars20 Password: CoolStars20 Click to accept the conditions then log in. ii Foreword Our story starts on January 31, 1980 when a small group of about 50 astronomers came to- gether, organized by Andrea Dupree, to discuss the results from the new high-energy satel- lites IUE and Einstein. Called “Cool Stars, Stellar Systems, and the Sun,” the meeting empha- sized the solar stellar connection and focused discussion on “several topics … in which the similarity is manifest: the structures of chromospheres and coronae, stellar activity, and the phenomena of mass loss,” according to the preface of the resulting, “Special Report of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.” We could easily have chosen the same topics for this meeting. Over the summer of 1980, the group met again in Bonas, France and then back in Cambridge in 1981. Nearly 40 years on, I am comfortable saying these workshops have evolved to be the premier conference series for cool star research. Cool Stars has been held largely biennially, alternating between North America and Europe. Over that time, the field of stellar astro- physics has been upended several times, first by results from Hubble, then ROSAT, then Keck and other large aperture ground-based adaptive optics telescopes. -

Thea Kozakis

Thea Kozakis Present Address Email: [email protected] Space Sciences Building Room 514 Phone: (908) 892-6384 Ithaca, NY 14853 Education Masters Astrophysics; Cornell University, Ithaca, NY Graduate Student in Astronomy and Space Sciences, minor in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences B.S. Physics, B.S. Astrophysics; College of Charleston, Charleston, SC Double major (B.S.) in Astrophysics and Physics, May 2013, summa cum laude Minor in Mathematics Research Dr. Lisa Kaltenegger, Carl Sagan Institute, Cornell University, Spring 2015 - present Projects Studying biosignatures of habitable zone planets orbiting white dwarfs using a • coupled climate-photochemistry atmospheric model Searching the Kepler field for evolved stars using GALEX UV data • Dr. James Lloyd, Cornell University, Fall 2013 - present UV/rotation analysis of Kepler field stars • Study the age-rotation-activity relationship of 20,000 Kepler field stars using UV data from GALEX and publicly available rotation⇠ periods Dr. Joseph Carson, College of Charleston, Spring 2011 - Summer 2013 SEEDS Exoplanet Survey • Led data reduction e↵orts for the SEEDS High-Mass stars group using the Subaru Telescope’s HiCIAO adaptive optics instrument to directly image exoplanets Hubble DICE Survey • Developed data reduction pipeline for Hubble STIS data to image exoplanets and debris disks around young stars Publications Direct Imaging Discovery of a ‘Super-Jupiter’ Around the late B-Type Star • And, J. Carson, C. Thalmann, M. Janson, T. Kozakis, et al., 2013, Astro- physical Journal Letters, 763, 32 -

The Sustainability of Habitability on Terrestrial Planets

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets REVIEW ARTICLE The sustainability of habitability on terrestrial planets: 10.1002/2016JE005134 Insights, questions, and needed measurements from Mars Special Section: for understanding the evolution of Earth-like worlds JGR-Planets 25th Anniversary B. L. Ehlmann1,2, F. S. Anderson3, J. Andrews-Hanna3, D. C. Catling4, P. R. Christensen5, B. A. Cohen6, C. D. Dressing1,7, C. S. Edwards8, L. T. Elkins-Tanton5, K. A. Farley1, C. I. Fassett6, W. W. Fischer1, Key Points: 2 2 3 9 10 11 2 • Understanding the solar system A. A. Fraeman , M. P. Golombek , V. E. Hamilton , A. G. Hayes , C. D. K. Herd , B. Horgan ,R.Hu , terrestrial planets is crucial for B. M. Jakosky12, J. R. Johnson13, J. F. Kasting14, L. Kerber2, K. M. Kinch15, E. S. Kite16, H. A. Knutson1, interpretation of the history and J. I. Lunine9, P. R. Mahaffy17, N. Mangold18, F. M. McCubbin19, J. F. Mustard20, P. B. Niles19, habitability of rocky exoplanets 21 22 2 1 23 24 25 • Mars’ accessible geologic record C. Quantin-Nataf , M. S. Rice , K. M. Stack , D. J. Stevenson , S. T. Stewart , M. J. Toplis , T. Usui , extends back past 4 Ga and possibly B. P. Weiss26, S. C. Werner27, R. D. Wordsworth28,29, J. J. Wray30, R. A. Yingst31, Y. L. Yung1,2, and to as long ago as 5 Myr after solar K. J. Zahnle32 system formation • Mars is key for testing theories of 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA, 2Jet Propulsion planetary evolution and processes 3 that sustain habitability -

Searching the Cosmos in Carl Sagan's Name at Cornell 9 May 2015

Searching the cosmos in Carl Sagan's name at Cornell 9 May 2015 more meaningful than a statue or a building." The institute was founded last year with the arrival at Cornell of astrophysicist Lisa Kaltenegger, its director. But it had been called the Institute for Pale Blue Dots as it geared up for work. The announcement Saturday morning by Druyan represents the institute's official launch. Druyan said she suggested the name change to Kaltenegger, who she described as a "kindred spirit" to Sagan. Kaltenegger happily agreed, Druyan said. © 2015 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. In this 1981 file photo, astronomer Carl Sagan speaks during a lecture. On Saturday, May 9, 2015, Cornell University announced that its Institute for Pale Blue Dots is to be renamed the Carl Sagan Institute. Sagan was famous for extolling the grandeur of the universe in books and shows like "Cosmos." He died in 1996 at age 62. (AP Photo/Castaneda, File) The Cornell University institute searching for signs of life among the billions and billions of stars in the sky is being named for—who else?—Carl Sagan. Cornell announced Saturday that the Carl Sagan Institute will honor the famous astronomer who taught there for three decades. Sagan, known for extolling the grandeur of the universe in books and shows like "Cosmos," died in 1996 at age 62. He had been battling bone marrow disease. Researchers from different disciplines including astrophysics, geology and biology work together at the institute to search for signs of extraterrestrial life. "This is an honor worth waiting for because it's really commensurate with who Carl was," Ann Druyan, Sagan's wife and collaborator, told The Associated Press. -

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland)

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland) American Astronomical Society August, 2019 100 — New Discoveries scope (JWST), as well as other large ground-based and space-based telescopes coming online in the next 100.01 — Review of TESS’s First Year Survey and two decades. Future Plans The status of the TESS mission as it completes its first year of survey operations in July 2019 will bere- George Ricker1 viewed. The opportunities enabled by TESS’s unique 1 Kavli Institute, MIT (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States) lunar-resonant orbit for an extended mission lasting more than a decade will also be presented. Successfully launched in April 2018, NASA’s Tran- siting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is well on its way to discovering thousands of exoplanets in orbit 100.02 — The Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Sur- around the brightest stars in the sky. During its ini- vey: Giant Planet and Brown Dwarf Demographics tial two-year survey mission, TESS will monitor more from 10-100 AU than 200,000 bright stars in the solar neighborhood at Eric Nielsen1; Robert De Rosa1; Bruce Macintosh1; a two minute cadence for drops in brightness caused Jason Wang2; Jean-Baptiste Ruffio1; Eugene Chiang3; by planetary transits. This first-ever spaceborne all- Mark Marley4; Didier Saumon5; Dmitry Savransky6; sky transit survey is identifying planets ranging in Daniel Fabrycky7; Quinn Konopacky8; Jennifer size from Earth-sized to gas giants, orbiting a wide Patience9; Vanessa Bailey10 variety of host stars, from cool M dwarfs to hot O/B 1 KIPAC, Stanford University (Stanford, California, United States) giants. 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology TESS stars are typically 30–100 times brighter than (Pasadena, California, United States) those surveyed by the Kepler satellite; thus, TESS 3 Astronomy, California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, Califor- planets are proving far easier to characterize with nia, United States) follow-up observations than those from prior mis- 4 Astronomy, U.C. -

Last Call for Life: Habitability of Terrestrial Planets Orbiting Red Giants and White Dwarfs

Last Call for Life: Habitability of Terrestrial Planets Orbiting Red Giants and White Dwarfs A dissertation presented by Thea Kozakis to The Department of Astronomy and Space Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Astronomy & Astrophysics Cornell University Ithaca, New York August 2020 c 2020 | Thea Kozakis All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Lisa Kaltenegger Thea Kozakis Last Call for Life: Habitability of Terrestrial Planets Orbiting Red Giants and White Dwarfs Abstract As a star evolves, the orbital distance where liquid water is possible on the surface of an Earth-like planet, the habitable zone, evolves as well. While stellar properties are relatively stable on the main sequence, post-main sequence evolution of a star involves significant changes in stellar temperature and radius, which is reflected in the changing irradiation at a specific orbital distance when the star becomes a red giant, and then later a white dwarf. To search planets in these systems for signs of life it is essential that we understand how stellar evolution influences atmospheric photochemistry along with detectable biosignatures. We use EXO-Prime, which consists of a 1D coupled climate/photochemistry and a line-by-line radiative transfer code, to model the atmospheres and spectra of habitable zone planets around red giants and white dwarfs, and assess the time dependency of detectable biosignatures. iii Biosketch Thea Kozakis was born in Suffern, New York and spent the majority of her childhood in Lebanon, New Jersey with her parents John and Jacqueline, her sisters Cassandra and Sydney, and several wonderful dogs. -

No Snowball Bifurcation on Tidally Locked Planets

Abbot Dorian - poster University of Chicago No Snowball Bifurcation on Tidally Locked Planets I'm planning to present on the effect of ocean dynamics on the snowball bifurcation for tidally locked planets. We previously found that tidally locked planets are much less likely to have a snowball bifurcation than rapidly rotating planets because of the insolation distribution. Tidally locked planets can still have a small snowball bifurcation if the heat transport is strong enough, but without ocean dynamics we did not find one in PlaSIM, an intermediate-complexity global climate model. We are now doing simulations in PlaSIM including a diffusive ocean heat transport and in the coupled ocean-atmosphere global climate model ROCKE3D to test whether ocean dynamics can introduce a snowball bifurcation for tidally locked planets. Abraham Carsten - poster University of Victoria Stable climate states and their radiative signals of Earth- like Aquaplanets Over Earth’s history Earth’s climate has gone through substantial changes such as from total or partial glaciation to a warm climate and vice versa. Even though causes for transitions between these states are not always clear one-dimensional models can determine if such states are stable. On the Earth, undoubtedly, three different stable climate states can be found: total or intermediate glaciation and ice-free conditions. With the help of a one-dimensional model we further analyse the effect of cloud feedbacks on these stable states and determine whether those stabalise the climate at different, intermediate states. We then generalise the analysis to the parameter space of a wide range of Earth-like aquaplanet conditions (changing, for instance, orbital parameters or atmospheric compositions) in order to examine their possible stable climate states and compare those to Earth’s climate states. -

Alexander Gerard Hayes Current Address Permanent Address 412 Space Science Bldg

Alexander Gerard Hayes Current Address http://www.alexanderghayes.com Permanent Address 412 Space Science Bldg. [email protected] 85 Olde Towne Rd. Ithaca, NY 14853-6801 (607) 793-7531 Ithaca, NY 14850 EDUCATION Ph.D. Planetary Science (Minor in Geology) California Institute of Technology April 2011 M.S. Planetary Science California Institute of Technology June 2008 M.Eng. Applied & Engineering Physics Cornell University Dec. 2003 B.A. Astronomy / Physics, Summa Cum Laude Cornell University May 2003 B.A. Astrobiology (College Scholar), Summa Cum Laude Cornell University May 2003 SELECT AWARDS / FELLOWSHIPS Feinberg Faculty Fellow, Weizmann Institute (2019) Sigma Xi Young Scholar Procter Prize (2008) Provost Research Innovation Award, Cornell Univ. (2018) AGU Outstanding Student Paper Award (2008, 2010) Young Scientist Award, World Economic Forum (2017) NASA Graduate Research Fellow (2008-2011) Zeldovich Medal, COSPAR / RAS (2016) Caltech Henshaw Fellow (2006-2008) Kavli Fellow, National Academy of Sciences (2014) David Delano Clark Award [for Masters' Thesis] (2004) NASA Early Career Fellow (2013) Distinction in all Subjects – Cornell University (2003) AGU Ronald Greeley Early Career Award (2012) Cornell University College Scholar (2000-2003) Miller Research Fellow (2011-2012) NASA Group Achievement Awards (MER/MSL/Cassini) TEACHING EXPERIENCE • A3150, Geomorphology [S19] • A4410, Experimental Astronomy [F13] • A3310, Planetary Image Processing [F15] • A1102/A1104, Our Solar System [S17,S18] • A6577, Planetary Surface Processes [S15,S17,S20] • A6500: Mars2020 Landing Sites [S16] • A2202, A Spacecraft Tour of the Solar Sys. [S14,F14-F20] • A6500: Mars2020 Instruments [F20] SELECT COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIPS / ADVISORY BOARDS • 2020 – Present: Panel Chair, Ocean Worlds & Dwarf Planets, 2023-2032 Planetary Science & Astrobiology Decadal Survey • 2018 – Present: U.S. -

The Ice Cap Zone: a Unique Habitable Zone for Ocean Worlds

Published in The Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society vol. 477, 4, 4627-4640 The Ice Cap Zone: A Unique Habitable Zone for Ocean Worlds Ramses M. Ramirez1 and Amit Levi2 1Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1, Tokyo, Japan 152-8550 2 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Traditional definitions of the habitable zone assume that habitable planets contain a carbonate- silicate cycle that regulates CO2 between the atmosphere, surface, and the interior. Such theories have been used to cast doubt on the habitability of ocean worlds. However, Levi et al (2017) have recently proposed a mechanism by which CO2 is mobilized between the atmosphere and the interior of an ocean world. At high enough CO2 pressures, sea ice can become enriched in CO2 clathrates and sink after a threshold density is achieved. The presence of subpolar sea ice is of great importance for habitability in ocean worlds. It may moderate the climate and is fundamental in current theories of life formation in diluted environments. Here, we model the Levi et al. mechanism and use latitudinally-dependent non-grey energy balance and single- column radiative-convective climate models and find that this mechanism may be sustained on ocean worlds that rotate at least 3 times faster than the Earth. We calculate the circumstellar region in which this cycle may operate for G-M-stars (Teff = 2,600 – 5,800 K), extending from ~1.23 - 1.65, 0.69 - 0.954, 0.38 – 0.528 AU, 0.219 – 0.308 AU, 0.146 – 0.206 AU, and 0.0428 – 0.0617 AU for G2, K2, M0, M3, M5, and M8 stars, respectively. -

Sarah Rugheimer

Sarah Rugheimer Contact Atmospheric Oceanic & Planetary Physics US Phone: +1 (617) 870-4913 Information Clarendon Laboratory, Oxford University UK Phone: +44 (0)7506 364848 Sherrington Rd, [email protected] Oxford, UK OX1 3PU http://users.ox.ac.uk/∼srugheimer/ Research I study the climate and atmospheres of habitable exoplanets. My research particularly Interests focuses on the star-planet interaction, studying the effect of UV activity on the atmo- spheric chemistry and the detectability of biosignatures in a planet's atmosphere with future missions such as JWST, E-ELT and LUVOIR. Appointments Glasstone Research Fellow, Oxford University Oct 2018 - present Glasstone Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Hugh Price Fellowship at Jesus College, Oxford Simons Research Fellow, University of St. Andrews Oct 2015 - Sept 2018 Simons Origins of Life Postdoctoral Research Fellow Research Associate, Cornell University, Carl Sagan Inst. Feb 2015 - Aug 2015 Education Harvard University, Cambridge, MA September 2008 - January 2015∗ M.A. in Astronomy June 2010 Ph.D. in Astronomy & Astrophysics June 2010 - January 2015 • Thesis Title: Hues of Habitability: Characterizing Pale Blue Dots Around Other Stars • Advisors: Lisa Kaltenegger and Dimitar Sasselov • Chosen as one of 8 PhD students at Harvard in Arts and Sciences as a 2014 Harvard Horizons Scholar: www.gsas.harvard.edu/harvardhorizons * Harvard recognized a 1.5 years delay in time caring for terminally ill father. University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta Canada B.Sc. (First Class Honors), Physics September 2003 - June 2007 • Graduated top of class in Department of Physics and Astronomy • Senior Thesis Topic: Uses of Attractive Bose-Einstein in Atom Interferometers • Undergrad summer research projects: placing quantum dots in phospholipid vesi- cles as a precursor to tracking active neuron cells with Dr. -

Hunting for Hidden Life on Worlds Orbiting Old, Red Stars 16 May 2016

Hunting for hidden life on worlds orbiting old, red stars 16 May 2016 like our sun, but to find habitable worlds, one needs to look around stars of all ages. In their work, Ramses M. Ramirez, research associate at Cornell's Carl Sagan Institute and Lisa Kaltenegger, associate professor of astronomy and director of the Carl Sagan Institute, have modeled the locations of the habitable zones for aging stars and how long planets can stay in it. Their research, "Habitable Zones of Post-Main Sequence Stars," is published in the Astrophysical Journal May 16. The "habitable zone" is the region around a star in which water on a planet's surface is liquid and signs of life can be remotely detected by telescopes. "When a star ages and brightens, the habitable zone moves outward and you're basically giving a second wind to a planetary system," said Ramirez. "Currently objects in these outer regions are frozen in our own solar system, and Europa and Enceladus - moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn - are icy for now." Dependent upon the mass (weight) of the original star, planets and their moons loiter in this red giant habitable zone up to 9 billion years. Earth, for example, has been in our sun's habitable zone so far for about 4.5 billion years, and it has teemed This graphic shows where a planet can be habitable and with changing iterations of life. However, in a few warm around our sun, as it ages over billions of years. billion years our sun will become a red giant, Credit: Cornell University engulfing Mercury and Venus, turning Earth and Mars into sizzling rocky planets, and warming distant worlds like Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune - and their moons - in a newly established red giant All throughout the universe, there are stars in habitable zone. -

Sylph-A Smallsat Probe Concept Engineered to Answer Europa's Big

SSC-XI-06 Sylph – A SmallSat Probe Concept Engineered to Answer Europa’s Big Question Travis Imken, Brent Sherwood, John Elliott, Andreas Frick, Kelli McCoy, David Oh, Peter Kahn, Arbi Karapetian, Raul Polit-Casillas, Morgan Cable Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA, 91101; 818-354-5608 [email protected] Jonathan Lunine Department of Astronomy and Carl Sagan Institute, Cornell University 402 Space Sciences Building, Ithaca, NY 14853; 607-255-5911 [email protected] Sascha Kempf, Ben Southworth, Scott Tucker Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder 1234 Innovation Dr., Boulder, CO 80303; 303-619-7375 [email protected] J. Hunter Waite Southwest Research Institute 6220 Culebra Road, San Antonio, TX 78228; 210-522-2034 [email protected] ABSTRACT Europa, the Galilean satellite second from Jupiter, contains a vast, subsurface ocean of liquid water. Recent observations indicate possible plume activity. If such a plume expels ocean water into space as at Enceladus, a spacecraft could directly sample the ocean by analyzing the plume’s water vapor, ice, and grains. Due to Europa’s strong gravity, such sampling would have to be done within 5 km of the surface to sample ice grains larger than 5 µm, expected to be frozen ocean spray and thus to contain non-volatile species critical to a biosignature-detection mission. By contrast, the planned Europa Multiple Flyby Mission’s closest planned flyby altitude is 25 km. Sylph is a concept for a SmallSat free-flyer probe that, deployed from the planned Europa Mission, would directly sample the large grains by executing a single ~2-km altitude plume pass.