241-404 Tourism 2011 03En.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powered by Toursoft

Exotic Himachal-Do not change-Copy1 8 Days/7 Nights Powered by TourSoft Key Attractions Top 15 Places To Visit In Himachal Pradesh If you like anything and everything about snow, you may be inspired by the meaning of the word Himachal. ‘The land of snows’, the meaning, is adequate to give you an idea of what to expect here. Himachal Pradesh is located in the western Himalayas. Surrounded by majestic mountains, out of which some still challenge mankind to conquer them, the beauty of the land is beyond imagination. Simla, one of the most captivating hill stations, is the capital of the state. Given below are the top 15 places to visit in Himachal Pradesh. 1. Kullu Image credit – Balaji.B, CC BY 2.0 Kullu in Himachal Pradesh is one of the most frequented tourist destinations. Often heard along with the name Manali, yet another famous tourist spot, Kullu is situated on the banks of Beas River. It was earlier called as Kulanthpitha, meaning ‘The end of the habitable world’. Awe-inspiring, right? Kullu valley is also known as the ‘Valley of Gods’. Here are some leading destinations in the magical land. - Basheshwar Mahadev Temple - Sultanpur Palace - Parvati Valley - Raison - Raghunathji Temple - Bijli Mahadev Temple - Shoja - Karrain Bathad - Jagatsukh The attractions in Kullu are more. Trekking, mountaineering, angling, skiing, white water rafting and para gliding are some of the adventurous sports available here. 2. Manali Image credit – Balaji.B, CC BY 2.0 Located at an altitude of 6726 feet, Manali offers splendid views of the snow-capped mountains. -

Editor's Note

channeling news from high altitude Himalayan wetlands EDITOR’S NOTE Dear Reader, Conservation teaches us new lessons everyday. Apart from opening our minds to novel and innovative solutions engineered to protect and conserve our ecosystems, it also humbles us by demonstrating the true, and often, immeasurable value of these ecosystems. But perhaps, one of the biggest lessons we have learnt is that conservation is not the privilege of a chosen few. It is a passion and a life skill which unites diverse groups of people, irrespective of their education, culture or nationality, resulting in productive partnerships. Such has been revealed to us through our regional efforts in conserving high altitude wetlands in the Himalayas. The ‘Saving Wetlands Sky-High!’ project has been a journey of discovering new conservation partners and of revelling in team-work. INSIDE Through this issue of ‘Himalayan Highlights’, we bring you stories of some of our Feature Story new and vibrant partners. We have found them in monasteries, at polo matches, Communities adopt their Wetlands on religious pilgrimages and in research institutions. We have found them in the Making a Difference young and in the old, in students and in preachers, in governments and in the Sporting Conservation people. We have found them in Pakistan, India, China, Nepal and Bhutan. But A Journey to New Learning most importantly, we have found them in the Himalayas. Gosaikunda breathes after Janaipoornima Cleanliness next to Godliness Read on to learn how the Himalayas and its ecosystems have inspired people to Strengthening through Science work together and have motivated them to make a difference. -

Hpidb Website 02.06.2018

Himachal Pradesh Infrastructure Development Board & Department of Tourism & Civil Aviation, Himachal Pradesh REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL WEBSITE for DevelopmentHPIDB of Ropeway between Sachuin (Bharmour) and Bharmani Mata Temple in Himachal Pradesh on PPP 02.06.2018Mode June 2018 Development of Ropeway between Sachuin (Bharmour) and Bharmani Mata Temple, Himachal Pradesh on PPP mode INSTRUCTIONSWEBSITE TO BIDDERS HPIDB 02.06.2018 Request for Proposal Document, Volume I: Instructions to Bidders 2 Development of Ropeway between Sachuin (Bharmour) and Bharmani Mata Temple, Himachal Pradesh on PPP mode Disclaimer The information contained in this Request for Proposal document (the “RFP”) or subsequently provided to Bidder(s), whether verbally or in documentary or any other form by or on behalf of Department of Tourism & Civil Aviation, Shimla (DOT &CA) / Himachal Pradesh Infrastructure Development Board (HPIDB) or any of its employees or advisors, is provided to Bidder(s) on the terms and conditions set out in this RFP and such other terms and conditions subject to which such information is provided. This RFP is not an agreement and is neither an offer nor invitation by DOT &CA / HPIDB to the prospective Bidders or any other person. The purpose of this RFP is to provide interested parties with information that may be useful to them in making their financial offers pursuant to this RFP. This RFP includes statements, which reflect various assumptions and assessments arrived at by DOT &CA / HPIDB in relation to the Project. Such assumptions, assessments and statements do not purport to contain all the information that each Bidder may require. This RFP may not be appropriate for all persons, and it is not possible for HPIDB, its employees or advisors to consider the investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs of each party who reads or uses this RFP. -

Primo.Qxd (Page 1)

BOOKING OPEN 2BHK/3BHK FLATS at Gurgaon, Noida, Noida Extension, Greater Noida Cont: 9419101229, 94191-76665 ENTRUST REALTORS & CONSULTANTS SUNDAY, AUGUST 25, 2013 INTERNET EDITION : www.dailyexcelsior.com/magazine www.jammuproperty.com PILGRIMAGE TO MANIMAHESH Kaushal Kotwal dis with a Chuhali topi (pointed cap), which they wear tra- ditionally along with their other dress of chola (coat) and The annual yatra of Manimahesh commences from Lax- dora (a long black cord about 10-15 m long). The Gaddis mi-Narayana Temple in Chamba in the month of August / started calling the land of this mountainous region as 'Shiv September. Also the scared Chhari of Lord Shiva is taken Bhumi' (Land of Shiva) and themselves as devotees of Shi- from different holy places of Chenab Valley of Bhadarwah va. The legend further states that before Shiva married Par- tehsil and adjoining areas of the tehsil Bhadarwah of dis- vati at Mansarovar Lake and became the "universal par- trict Doda. In this sacred yatra chelas of Lord Shiva along- ents of the universe", Shiva created the Mount Kailash in with many devotees of Lord Shiva proceed to Manimahesh Himachal Pradesh and made it his abode. He made Gad- tirth in Himachal Pradesh. Some accompany the chhari and dis his devotees. The land where Gaddis lived extended some go directly to Himachal Pradesh. The Chhari is tak- from 15 miles (24 km) west of Bharmaur, upstream of the en to the sacred lake of Manimahesh, which is one of the confluence of Budhil and Ravi rivers, up to Manimahesh. chief tirthas in the district. -

Hemkund | Manimahesh

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Holy Lakes of India Nanital | Gurudongmar | Hemkund | Manimahesh Copyright © 2019, DollsofIndia India, being one of the most ancient civilizations of the world, is rich in art, culture, mythology and traditions. With its diverse population and innumerable schools of religious and philosophical thought, it also abounds with vastly different and colourful rituals and ceremonies. Indians have great respect not only for their deities and other divine beings, but also for pilgrimage sites, holy mountains, springs, rivers and lakes, which are sometimes considered to be as sacred as the Gods themselves. In our previous post, we brought you a list of some of the most important and sacred lakes of India. This month, we bring you Part II of our article, "Holy Lakes of India". This time, we bring you a detailed feature on Nainital, Gurudongmar, Hemkund and finally, the majestic Manimahesh. Nainital Nainital, also referred to as Naini Tal, is a popular hill station in Uttarakhand in the Kumaon foothills of the outer Himalayas. Located at a height of 2,084 meters above sea level, this picturesque place is set in a valley, surrounded by mountains, and containing an eye-shaped lake, about 2 miles in circumference. The highest point closest is Naina Peak or China Peak, with an elevation of 2,619 meters. Nainital is considered to be one of the most brilliant diamonds of the Himalayan Belt. This city has 3 major lakes, which contribute to keeping the place cool and serene all through the year. Legend According to legend, Naini Lake is one of the 51 Shakti Peethas. -

Annual Report 2015-16

INTACH Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage Annual Report 2015-16 The INTACH Logo, based on the anthropomorphic copper figure from Shahabad, Uttar Pradesh, belonging to the enigmatic Copper Hoards of the Ganga Valley is the perceived brand image of INTACH. The classic simplicity and vitality of its lines makes it a striking example of primitive man’s creative genius. (circa 1800-1700 BC.) INTACH’s mission to conserve heritage is based on the belief that living in harmony with heritage enhances the quality of life, and it is the duty of every citizen of India as laid down in the Constitution of India. INTACH Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage Annual Report 2015-16 Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) was founded with the vision to create a membership organization to stimulate and spearhead heritage awareness and conservation in India. Today INTACH is recognized as one of the world’s largest heritage organizations, with over 185 Chapters across the Country. CONTENTS 5 Message from Chairman 6 Message from Member Secretary 10 Governing Council and Executive Committee 12 Other Committees 17 EVENTS 29 CONSERVATION 59 DOCUMENTATION 77 TRAINING AND OUTREACH 105 PUBLICATIONS 113 ACTIVITIES OF THE CHAPTERS 134 Legal Cell 135 Audited Accounts 2015-2016 159 Acknowledgements BACKGROUND: Documented wall paintings – Sita Ram Kalyanji Temple; PAGE 4: Work in progress in Laxminath Temple, Jolpa. OBJECTIVES OF INTACH The main aim and objectives of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) are: To create and stimulate an awareness among the public for the preservation of the cultural and natural heritage of India. -

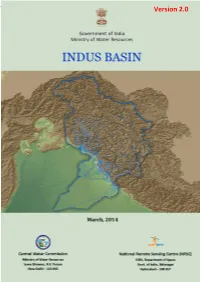

Purpose of Hydroelectric Generation.Only 13 Dams Are Used for Flood Control in the Basin and 19 Dams Are Used for Irrigation Along with Other Usage

Indus (Up to border) Basin Version 2.0 www.india-wris.nrsc.gov.in 1 Indus (Up to border) Basin Preface Optimal management of water resources is the necessity of time in the wake of development and growing need of population of India. The National Water Policy of India (2002) recognizes that development and management of water resources need to be governed by national perspectives in order to develop and conserve the scarce water resources in an integrated and environmentally sound basis. The policy emphasizes the need for effective management of water resources by intensifying research efforts in use of remote sensing technology and developing an information system. In this reference a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on December 3, 2008 between the Central Water Commission (CWC) and National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to execute the project “Generation of Database and Implementation of Web enabled Water resources Information System in the Country” short named as India-WRIS WebGIS. India-WRIS WebGIS has been developed and is in public domain since December 2010 (www.india- wris.nrsc.gov.in). It provides a ‘Single Window solution’ for all water resources data and information in a standardized national GIS framework and allow users to search, access, visualize, understand and analyze comprehensive and contextual water resources data and information for planning, development and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). Basin is recognized as the ideal and practical unit of water resources management because it allows the holistic understanding of upstream-downstream hydrological interactions and solutions for management for all competing sectors of water demand. -

Conflicts and Connections in the Landscape of the Manimahesh

Jonathan Miles-Watson and Sukanya B. Miles-Watson Confl icts and connections in the landscape of the Manimahesh pilgrimage Abstract Th ere is a signifi cant, established, record of academic discussion of Himalayan pilgrimages, which when taken together, direct understandings of pilgrimage in this region in a way that draws attention to some aspects of the landscape of Himalayan pilgrimage while ignoring others. Th is paper seeks to add something new to the ever-expanding literature on pilgrima- ge in this region by disrupting this process through the presentation of a collaborative auto- ethnography, which focuses on the landscape of a locally important, yet hitherto internatio- nally ignored, Himalayan pilgrimage: the Manimahesh pilgrimage of the Chamba District of Himachal Pradesh. It emerges that, while fellow pilgrims mutually constitute each other's pilgrimage experience, the exact nature of that experience varies depending on the pilgrim's skill to reckon with the environment that they are entering into. What is more, the confl ic- ting nature of pilgrimage experiences becomes intensifi ed after the pilgrimage during the pilgrims' structured attempts to narrativise their experience for others. Key words: Himalayan pilgrimage; anthropology; Hinduism; landscape theory; India Introduction In early September 2009 we were at our neighbour's house in Shimla, the state capital of Himachal Pradesh. Although outside our window the treetops swayed peacefully in the wind, inside the house there was an increasing air of frustration. We had just returned from a pilgrimage in the north of the Hill State and we were trying to relate the experience of this to our neighbour, who had been left lame when the bus she had been travelling on went off the road (sadly, a common occurrence in Himachal Pradesh). -

State of the Rivers Report Final 2017- Himachal Pradesh

DRIED & STATE OF THE RIVERS - HIMACHAL PRADESH DUSTED HIMDHARA ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH AND ACTION COLLECTIVE INDIA RIVERS WEEK 2016 0 Dried & Dusted State of the Rivers Report – Himachal Pradesh India Rivers Week 2016 Prepared by Himdhara Environment Action and Research Collective November 2016 Dried & Dusted State of the Rivers Report for Himachal Pradesh Prepared for the India Rivers Week 2016 Author: Himdhara Environment Research and Action Collective Maps: SANDRP, Maps Of India, EJOLT Cover Photo: Nicholas Roerich – ‘Chandra-Bhaga. Path to Trilokinath. Tempera on Canvas. Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York, USA.’ November 2016 Material from this publication can be used, with acknowledgment to the source. Introduction The lifelines of Himalayas A massive collision between two tectonic plates of the Indian and Eurasian land masses about 50 to 70 million years ago led to the formation of the youngest and tallest mountain ranges, the Himalayas. Once the Himalayas started to rise, a southward drainage developed which subsequently controlled the climate of the newly formed continent, and there started the season of monsoon as well. The river systems of the Himalayas thus developed because of rains and melting snow. The newly formed rivers were like sheets of water flowing towards the fore-deep carrying whatever came in their way. Once the rivers reached the plains their gradients became lesser, their hydraulics changed and they started to deposit their sediment (Priyadarshi, 2016). The river is a defining feature of a mountain eco-system. And if that ecosystem is the Himalayas then this makes the rivers originating here special for several reasons. Their origin and source to start with, which includes glaciers and snow bound peaks; their length and size, and the area they cover is larger than most peninsular rivers; their rapid, high velocity, meandering flow which is constantly shaping the young and malleable Himalayan valleys; their propensity to carry silt and form rich plains to facilitate a fertile agriculture downstream is another unique feature. -

Himachal Pradesh State

Himachal Pradesh State (pop., 2008 est.: 6,550,000), northern India. The earliest known inhabitants of the region were tribals called Dasas. Later, Aryans came and they assimilated in the tribes. In the later centuries, the hill chieftains accepted suzerainty of the Mauryan empire, the Kaushans, the Guptas and Kanuaj rulers. During the Mughal period, the Rajas of the hill states made some mutually agreed arrangements which governed their relations. In the 19th century, Ranjit Singh annexed/subjugated many of the states. When the British came, they defeated Gorkhas and entered into treaties with some Rajas and annexed the kingdoms of others. The situation more or less remained unchanged till 1947. After Independence, 30 princely states of the area were united and Himachal Pradesh was formed on 15th April, 1948. With the recognition of Punjab on 1st November, 1966, certain areas belonging to it were also included in Himachal Pradesh. On 25th January, 1971, Himachal Pradesh was made a full‐fledged State. The State is bordered by Jammu & Kashmir on North, Punjab on West and South‐West, Haryana on South, Uttar Pradesh on South‐East and China on the East. General Location Latitude 30o 22' 40" N to 33o 12' 40" N Longitude 75o 45' 55" E to 79o 04' 20" E Height (From mean sea Level) 350 meter to 6975 meter Population [2001‐Census] 6077248 persons Urban 594881 persons Rural 5482367 persons Geographical Area [2001] 55,673 sq. km Density (per Sq. Km.) [2001] 109 Females per 1000 Males [2001] 970 Birth Rate (per 1000) [2002(P)] 22.1 Death Rate (per 1000) [2002(P)] 7.2 Administrative Structure [2002] State Capital Shimla No. -

ECO VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT PLAN Village

ECO VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT PLAN (EVDP) Village - Bhanjraru Block Tissa, District Chamba Himachal Pradesh Developed by: Department of Environment, Science & Technology Government of Himachal Pradesh Paryavaran Bhawan, Shimla-171001 Model Eco Village Scheme- A brief Note The Government of Himachal Pradesh has notified a Model Eco Village Scheme vide notification No. STE-A(3)-4/2016-L dated 26/9/2017. This scheme is being implemented by the Government of Himachal Pradesh through Department of Environment, Science & Technology & concerned Block Development Office and district administration aiming to ensure sustainable development in an organized and integrated manner. The programme endeavors to sustain prosperity in villages that is built around sustainable use of the key natural resources of a village, through the adoption of low-impact practices that result in water security, food security and livelihood security for the village communities. Under this scheme a village will be developed to promote transformative action and achieve sustainable development through environmentally responsible and responsive practices in the area of water management, waste management, energy conservation, management of natural resources, climate change action and sustainable livelihoods. This approach will not only help those stakeholders who are working to implement sustainable community development programme but also will set benchmarks for others to adopt and bring a radical change in thinking process of the communities at large in the State, especially in inculcating environmentally responsible behavior. This scheme is to be implemented in the selected village with the total financial outlay of Rs. 50 lakhs to be utilized over a period of 5 years as per the annual plan of action. -

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies Analyzing Resource Potential for Nature Based Tourism

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies ISSN NO:: 2348 – 537X Analyzing Resource Potential for Nature Based Tourism: A Case Study of the State of Himachal Pradesh (India) Punit Gautam Associate Professor, Department of Tourism and Hotel Management, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya (India) ―Potential‖ broadly insinuates something promising but not yet (fully) exploited; it symbolizes the sum total of qualitative and quantitative values of the given resources on which the degree and extent of its exploitability depends (Kandari, 1984). In the context of tourism, assessing the resource potential in quantitative terms is highly complex process, if not impossible, as it involves the physical, psychological and spiritual demands on the people belonging to diverse geographical, socio-cultural and economic backgrounds who travel under different motives, interests, preferences and immediate needs. To quote Kandari (1984), ―potential for tourism development in any area depends on the availability of recreational resources in addition to the factors like climate, seasons, accessibility, proximity to market, political stability, state of economy and general infrastructure, quality of natural environment, attitude of the local people, travel trade entrepreneurs and tourism planners, the existing tourist plant facilities and the degree to which they can be further developed within the prevailing limitations of natural, cultural and financial environments. Healthy combination of all those and many other factors