Children and Interactive Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interactive Media Program

Interactive Media Production Students enrolled in Interactive Media Production will discover the fundamental elements of effective visual communication including sound, video and motion graphics. Media literacy and ethics relating to design are emphasized while creating media appropriate for the client and target audience. Parameters relating to color, resolution, and composition will determine the design process. Students develop problem solving skills, working independently as well as in teams, aligning the workflow of a typical commercial operation, based on the three pathway areas. 1. Graphic Design: Plan and project ideas and experiences with visual and textual content, and illustrate art concepts and skills, including composition, lighting, color theory, drawing, and painting, basic photography, and typography. 2. Digital Media: Encode or digitally compress audio, video, and photo content into a digital media file, and manipulate, distribute, and play media files over computer networks. 3. Interactive Media: Integrate digital media, including combinations of electronic text, graphics, moving images, and sound, into a structured digital computerized environment that allows people to interact with the data for appropriate purposes. The program is outfitted with an industry-standard Macintosh computer lab, with Adobe products, enabling the students to create exceptional results in print, web, interactive and mobile design. Students will learn basic camera operations with state of the art equipment. The course also introduces students to document construction for publishing on the World Wide Web using authoring software. Hands-on activities are used as students develop skills, master techniques, and prepare products for a client-based environment. Required Courses: All three (3) of these courses are required to achieve Completer Status. -

Choosing Between Communication Studies and Film Studies

Choosing Between Communication Studies and Film Studies Many students with an interest in media arts come to UNCW. They often struggle with whether to major in Communication Studies (COM) or Film Studies (FST). This brief position statement is designed to help in that decision. Common Ground Both programs have at least three things in common. First, they share a common set of technologies and software. Both shoot projects in digital video. Both use Adobe Creative Suite for manipulation of digital images, in particular, Adobe Premiere for video editing. Second, they both address the genre of documentaries. Documentaries blend the interests of both “news” and “narrative” in compelling ways and consequently are of interest to both departments. Finally, both departments are “studies” departments: Communication Studies and Film Studies. Those labels indicate that issues such as history, criticism and theories matter and form the context for the study of any particular skills. Neither department is attempting to compete with Full Sail or other technical training institutes. Critical thinking and application of theory to practice are critical to success in FST and COM. Communication Studies The primary purposes for the majority of video projects are to inform and persuade. Creativity and artistry are encouraged within a wide variety of client- centered and audience-centered production genres. With rare exception, projects are approached with the goal of local or regional broadcast. Many projects are service learning oriented such as creating productions for area non-profit organizations. Students will create public service announcements (PSA), news and sports programming, interview and entertainment prog- rams, training videos, short form documentaries and informational and promotional videos. -

Interactive Media 1

Interactive Media 1 INTERACTIVE MEDIA http://com.miami.edu/programs Dept. Code: CIM Introduction The Department of Interactive Media offers major in Interactive Media and minors in Game Design (GAME) and Interactive Media (CIMI). The Department of Interactive Media strives to foster active learning in the design and research of technologies that improve society and people's lives. Our hands-on curriculum allows students to explore the role that interactive technologies play in communication and how they shape our world. The majors and minors offered by the Department of Interactive Media are designed to enable students to customize their education within a learning environment that is collaborative and conducive to the pursuit, exchange, and development of ideas and information. The curriculum also further provides students with the tools necessary to succeed in a range of careers defined by a rapidly changing technology and media landscape and equips them to best leverage interactivity, emerging technologies, and innovative developments in the field. Goals of the Program are: • To provide students with the technical and practical skills needed to make them career-ready through hands-on learning, problem- solving based inquiry, and advanced study. • To nurture the individual talent, creativity, and discovery process of every student by fostering principles of collaboration, professionalism, and intellectual curiosity. • To support the educational process through mentoring and advising by renowned faculty and seasoned professionals. • To encourage students to integrate theory and practice, to cultivate the capacity to think critically, and to connect technology and art and/or design. • To familiarize students with theoretical, historical, and cultural approaches and expose them to a range of traditions within the field of study. -

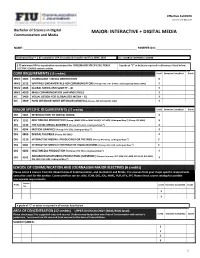

Digital + Interactive Media

Effective Fall 2020 Last revised: 10/30/20 Bachelor of Science in Digital MAJOR: INTERACTIVE + DIGITAL MEDIA Communication and Media NAME: ______________________________________________________________________________ PANTHER ID #: _ Undergrad Reqs*= 2.85 cumulative GPA (including all transfer and FIU), MMC 3003 GL = GLOBAL LEARNING COURSE 2.75 minimum GPA is a graduation requirement for CORE/MAJOR SPECIFIC/SCJ TRACK A grade of “C” or better is required in all courses listed below. ELECTIVE COURSE sections below. CORE REQUIREMENTS (15 credits) Credit Semester Completed Grade MMC 3003 JOURNALISM + MEDIA ORIENTATION 0 MMC 3123 WRITING FUNDAMENTALS FOR COMMUNICATORS (Prereq: ENC 1101 & ENC 1102) (replaced MMC 3104C) 3 MMC 3303 GLOBAL MEDIA AND SOCIETY – GL 3 MMC 4200 MASS COMMUNICATION LAW AND ETHICS 3 VIC 3400 VISUAL DESIGN FOR GLOBALIZED MEDIA – GL 3 IDS 3309 HOW WE KNOW WHAT WE KNOW (GRW/GL) (Prereq: ENC 1101 & ENC 1102) 3 MAJOR SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS (27 credits) Credit Semester Completed Grade DIG 3001 INTRODUCTION TO DIGITAL MEDIA 3 RTV 3531 MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION (Prereq: (MMC 3123 or MMC 3104C), VIC 3400, Undergrad Reqs*) (Coreq: VIC 3400) 3 DIG 3146 THE SOCIAL MEDIA AUDIENCE (Prereq: RTV 3531, Undergrad Reqs*) 3 DIG 4394 MOTION GRAPHICS (Prereq: RTV 3531, Undergrad Reqs*) 3 DIG 4800 DIGITAL THEORIES (Prereq: DIG 3001) 3 DIG 3110 INTERACTIVE MEDIA I: PRODUCING FOR THE WEB (Prereq: RTV 3531, Undergrad Reqs*) 3 DIG 3181 INTERACTIVE MEDIA II: INTERACTIVE VISUALIZATIONS (Prereq: DIG 3110, Undergrad Reqs*) 3 DIG 4293 MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION II (Prereq: RTV 3531, Undergrad Reqs*) 3 DIG 4552 ADVANCED MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION [CAPSTONE] (Prereq: Core reqs, DIG 3146, DIG 4800, DIG 3110, DIG 4293, 3 DIG 4394, DIG 3181, Undergrad Reqs*) SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION AND JOURNALISM MAJOR ELECTIVES (6 credits) Please select 2 courses from the departments of Communication, and Journalism and Media. -

Digital Arts

DIGITAL ARTS PROGRAMS . Associate of Arts (A.A.) . Certificate of Achievement DESCRIPTION TRANSFER PREPARATION The Digital Arts program offers a certificate and associate degree in Courses that fulfill major requirements for an associate Digital Arts. Classes include training in graphic design, digital graphics, degree may differ from those 2D digital illustration, 2D digital photographic imaging, digital video needed to prepare for transfer. and audio editing, 2D and 3D digital animation, 3D modeling, Students who plan to transfer to storyboard development for animation and interactive digital media a four‐year college or university interface design. The AA degree in Digital Arts offers 3 tracks of should schedule an appointment specialization; graphic design for print, screen and time‐based, digital with a Hartnell College counselor photography and video, or digital animation and illustration. An to develop a student education imaginative blend of art, design, photography, video, animation and plan before beginning their illustration is applied to producing digital media presentations for program. business, education, entertainment, telecommunication and medical TRANSFER RESOURCES industries graduates in Digital Arts are qualified for positions in graphic design, digital art, web design, game design, 2D illustration, www.ASSIST.org – CSU and UC digital photographic imaging, audio engineering, video editing, digital Articulation Agreements and video, or digital media interface design. Graduates in Digital Arts with Major Search Engine animation specialization are qualified for positions in 3D digital art, CSU System Information ‐ game design, storyboard art, 3D modeling, character animation, http://www2.calstate.edu digital 3D broadcast logo design, digital 3D volumetrics, 3D animation and compositing, 2D digital art, 2D compositing, 2D chroma key, 2D FINANCIAL AID texture painting, or rotoscoping. -

Interactive Media Art: the Institution Tells a Story

Interactive Media Art: the institution tells a story. The Center for Art Media Karlsruhe | 181 Interactive Media Art: the Institution Tells a Story. The Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe Media Art Interactivo: la Institución cuenta una historia. El Centro para el Arte y Media Karlsruhe Sónia Alves Interactive Media Art Researcher Fecha de recepción: 2 de mayo de 2014 Fecha de revisión: 11 de julio de 2014 Para citar este artículo: Alves, S. (2014): Interactive Media Art: the In- stitution Tells a Story. The Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Icono 14, volumen (12), pp. 181-205. doi: 10.7195/ri14.v12i2.709 DOI: ri14.v12i2.709 | ISSN: 1697-8293 | Año 2014 Volumen 12 Nº 2 | ICONO14 182 | Sónia Alves Abstract Interactive Media Art has been scrutinized under several approaches. It is though hard to achieve consensually a clear definition or conceptualization of this term. What I propose here is to follow a case study of an institution, the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, whose contributions for the development of this art form are unique and represent a continuous and profound achievement to the art world. At the same time this research calls the attention for another way to look at the devel- opments of Interactive Media Art by considering the institutional investment in the production of art. Simultaneously I will show that there is a pragmatical, education- al and pedagogical line of research in the history of Interactive Media Art that has not received much attention until now. Key Words: Interactive Media Art - History - Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe - Institutional Practice in Art - Artistic Production - Educational Practice - Science - Technology - Interactivity Resumen El “Interactive Media Art” ha sido examinado bajo distintos enfoques. -

Interactive Media

Interactive Media Pr isc illa Gran tham, Esq. Sr. Research Counsel National Center for Justice and the Rule of Law 1 Objectives After this session, you will be able to: Explain the concept behind the terms interactive media, Web 2.0, and Social Media; Identify different types of interactive media; Differentiate between various kinds of interactive media; and Summarize the ways in which interactive media are utilized. 2 But What Does It Mean? Interactive Web 2.0 Media Social MdiMedia A new model that utilizes user participation 3 Web 2.0 • Phrase coined in 2004 @ conference addressi ng st at e of W eb f oll owi ng dot-com crash. • Implied improvement over the old web • Democratization of web 4 Emphasis on people’s interactions with Internet Web sites harness collective intelligence of contributors/users Company can provide better service & build customer loyalty by observing Internet habits New Web Model 5 Media: Traditional v. Interactive Media = An instrument of communication Media in which users Interactive Media = participate & edit content of communication 6 Media 7 Interactive Media: “Hybrid Media Technology” – can combine anyy(p,, format (print, web, disc, video, audio, etc.) that allows users to interact w/ content. 8 Interactive Media Model: USER’S INPUT PROGRAM’S OUTPUT 9 Media v. Interactive Media 10 Encyclopedia v. Wikipedia Encyclopedias Wikipedia • Difficult to keep current • Updated constantly • Expensive to produce •Free and purchase • All contributors must cite • Inconsistencies / published sources Inaccuracies in info • Content must have • Bias & lack of expertise neutral POV of authors • No limitation on topics • Editorial choices • Anyone can edit an • Past allegations of article racism and sexism 11 Information being communicated: How the Internet works 12 Information being communicated: How the World Wide Web works http://www.commoncraft.com User can watch video online User can purchase & download on Kindle User can share video via Twitter or Email Written overview User can download transcript of video Download Fact Sheet [PDF]. -

Unit 12: Understanding the Interactive Media Industry

Unit 12: Understanding the Interactive Media Industry Unit code: L/600/6686 QCF Level 3: BTEC National Credit value: 10 Guided learning hours: 60 Aim and purpose This unit aims to give learners an understanding of organisational structures and employment opportunities in the interactive media industry. Learners will look at how to prepare personal career development plans and material. The unit also covers contractual, legal and ethical obligations and regulatory issues. Unit introduction The interactive media industry is hard to define due to its rapid growth and overlap with many other industries. Interactive media products have the potential to transform and enhance our lives because they place the user at the centre of the experience. The industry creates a wide variety of content for the internet, computers, games consoles, mobile devices, wearables, interactive televisions, kiosks, digital advertising screens and other emerging technologies. In addition to developing skills for a specific role within the industry, individuals also need to have an overview of the structure of the industry and be aware of how their role interacts with that of others. The expanding interactive media industry consists of many different types of business each requiring individuals with multi-disciplinary skills. Businesses range in size from self-employed individuals working from home to large corporate organisations with thousands of employees. Much of the work done is for other organisations and is arranged through contracts or sub-contracts often as a result of a tender process. The success, survival and development of businesses in the interactive media industry depend not only on creative and technical skills but also on a wider understanding of the professional practices essential to working in the industry. -

The Potential of Interactive Media and Their Relevance in the Education Process

The Potential of Interactive Media and Their Relevance in the Education Process Dorota Siemieniecka * Wioletta Kwiatkowska** Kamila Majewska **** 1 Małgorzata Skibińska **** 1 * Assoc. Prof., PhD, Vice Dean of Faculty of Education, Chair of Disability Studies, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Lwowska Str. 1, 87-100 Torun, Poland e-mail: [email protected] ** Assist. Prof. PhD, Chair of Didactics and Media in Education, Faculty of Education, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Lwowska Str. 1. , 87-100 Torun, Poland e-mail: [email protected] *** Assist. Prof. PhD, Chair of Didactics and Media in Education, Faculty of Education, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Lwowska Str. 1. , 87-100 Torun, Poland e-mail: [email protected] **** Assist Prof. PhD, Chair of Didactics and Media in Education, Faculty of Education, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Lwowska Str. 1. , 87-100 Torun, Poland e-mail: [email protected] 1 International Journal of Psycho-Educational Sciences, Vol. 6, Issue (3), December –2017 Abstract: The article discusses the importance of interactive media in the teaching-learning process in the light of selected educational theories and research. The potential of social media to initiate and develop interactive learning communities was also demonstrated. Attention was drawn to the need for an appropriately prepared teacher, ready to creatively initiate educational situations involving interactive media and supporting student activities. Keywords: education, interaction, interactivity, information skills, social media Introduction In education, we can see increasingly evolving trends, manifested by the rapid development of interactive media and their use by a human being, taking into account his active participation. Narration has been transferred to an interactive environment in cyberspace or applications enabling exploration and multi-sensory learning in a fuller and more conscious way. -

Interactive Multimedia: Defining a Place in History

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 1997 Interactive multimedia: Defining a place in history Erika Sears Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Sears, Erika, "Interactive multimedia: Defining a place in history" (1997). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A thesis submitted to the faculty of the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences in candidacy for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Interactive Multimedia: Defining A Place in History by: Erika Sears 1997 Understanding Interactive Multimedia: Defining A Place in History Thesis Approval Chief Advisor: Nancy Ciolek Date: _---=-7--=--3~/_·---!!.-CJ---L-7 _ Associate Advisor: Jim VerHague _ Date: 9, IS 97 Associate Advisor: Frank Romano Date: '1- {I.. cr7 Department Chairperson: Nancy Ciolek Date: _~q_.--,---,1.>"'--.-,.ll-t..L-1 _ By: Erika Sears _ 7-+!_2._7-fA~9_L7~ Date: I; __ I, , hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT to reproduce my thesis in whole or part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profi t. Understanding Interactive Multimedia: Defining A Place in History Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction to Thesis (pg 4) Section 2: Goals & Ideation (pg 5-7) Section 3: Process & Materials (pg 8-11) Section 4: Review of Literature (pg 12-38) /. -

Technology and Interactive Media As Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8

POSITION STATEMENT ADOPTED JANUARY 2012 A joint position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children and the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8 elevision was once the newest technology media. When the inte- in our homes, and then came videos and gration of technology Interactive media refers to digital computers. Today’s children are growing and interactive media and analog materials, including soft- up in a rapidly changing digital age that is in early childhood ware programs, applications (apps), Tfar different from that of their parents and grandpar- programs is built broadcast and streaming media, some ents. A variety of technologies are all around us in upon solid develop- our homes, offices, and schools. When used wisely, mental foundations, children’s television programming, technology and media can support learning and and early childhood e-books, the Internet, and other forms relationships. Enjoyable and engaging shared expe- professionals are of content designed to facilitate active riences that optimize the potential for children’s aware of both the and creative use by young children and learning and development can support children’s challenges and the to encourage social engagement with relationships both with adults and their peers. opportunities, educa- other children and adults. Thanks to a rich body of research, we know much tors are positioned about how young children grow, learn, play, and to improve program develop. There has never been a more important time to quality by intention- apply principles of development and learning when con- ally leveraging the potential of technology and media for sidering the use of cutting-edge technologies and new the benefit of every child. -

Design and Multimedia Arts

COURSES LEVEL 1 NS IO AT IC N U M M O LEVEL 2 C D DESIGN & N A Y Y MULTIMEDIA G O ARTS L O N H LEVEL 3 C E T V / A , S T R A LEVEL 4 MASTER ’S/ MEDIAN ANNUAL % HIGH SCHOOL/ ' OCCUPATIONS CERTIFICATE/ ASSOCIATE S’ BACHELOR’S DOCTORAL WAGE OPENINGS GROWTH INDUSTRY ' ' LICENSE* DEGREE DEGREE PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATION DEGREE WORK BASED LEARNING AND EXPANDED LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES COURSE INFORMATION COURSE NUMBER AND PREREQUISITES (PREQ) COURSE NAME GRADE CREDITS COREQUISITES (CREQ) Principles of Arts, AV, Technology and 8510 (1 credit) None 9-10 Communications Principles of Arts, AV, Graphic Design & Illustration 8514 (1 credit) Technology and 10-11 Communications Digital Media 8641 (1 credit) Graphic Design & Illustration 11-12 Digital Art & Animation 8643 (1 credit) Digital Media 12 Graphic Design & Illustration OR Web Technologies 8642 (1 credit) Digital Media OR Digital Art and 11-12 Animation Career Preparation I 8606 (3 credits) None 12 COURSE DESCRIPTIONS Principles of Audio/Video: This course is designed to develop basic technical writing and communication skills utilizing Apple iMacs and applications, the Adobe Creative Suite, Final Cut Pro, and Cannon cameras. Students will focus on pre-production, production, and post-production video editing skills with a strong introduction to industry standards. Within this context, students will be expected to develop an understanding of the various and multifaceted career opportunities in this cluster. Graphic Design & Illustration: Articulated Credit: GD101-Art Institute Students will develop skills in illustration for published media and creative interpretation as well as creating graphics used for commercial art.