Summer 2006 Gems & Gemology Gem News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phenomenal Gemstones Possess Striking Optical Effects, Making Them Truly a Sight for Sore Eyes

THE PHENOMENAL PROPERTIES OF GEMS Phenomenal gemstones possess striking optical effects, making them truly a sight for sore eyes. Here is GIA’s guide to understanding what makes each phenomenon so uniquely brilliant. ASTERISM CROSSING BANDS OF REFLECTED LIGHT CREATE A SIX-RAYED STAR-LIKE APPEARANCE. ASTERISM OCCURS IN THE DOME OF A CABOCHON, AND CAN BE SEEN IN GEMS LIKE RUBIES AND SAPPHIRES. ADULARESCENCE THE SAME SCATTERING OF LIGHT THAT MAKES THE SKY BLUE CREATES A MILKY, BLUISH-WHITE GLOW, LIKE MOONLIGHT SHINING THROUGH A VEIL OF CLOUDS. MOONSTONE IS THE ONLY GEM THAT DISPLAYS IT. AVENTURESCENCE FOUND IN NATURAL GEMS LIKE SUNSTONE FELDSPAR AND AVENTURINE QUARTZ, IT DISPLAYS A GLITTERY EFFECT CAUSED BY LIGHT REFLECTING FROM SMALL, FLAT INCLUSIONS. CHATOYANCY OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE “CAT’S EYE” EFFECT, BANDS OF LIGHT ARE CAUSED BY THE REFLECTION OF LIGHT FROM MANY PARALLEL, NEEDLE-LIKE INCLUSIONS INSIDE A CABOCHON. NOTABLE GEMS THAT DISPLAY CHATOYANCY INCLUDE CAT’S EYE TOURMALINE AND CAT’S EYE CHRYSOBERYL. IRIDESCENCE ALSO SEEN IN SOAP BUBBLES AND OIL SLICKS, IT’S A RAINBOW EFFECT THAT IS CREATED WHEN LIGHT IS BROKEN UP INTO DIFFERENT COLORS. LOOK FOR IT IN FIRE AGATE AND OPAL AMMONITE (KNOWN BY THE TRADE AS AMMOLITE). LABR ADORESCENCE A BROAD FLASH OF COLOR THAT APPEARS IN LABRADORITE FELDSPAR, IT’S CAUSED BY LIGHT INTERACTING WITH THIN LAYERS IN THE STONE, AND DISAPPEARS WHEN THE GEM IS MOVED. INSIDER’S TIP: THE MOST COMMON PHENOMENAL COLOR IN LABRADORITE IS BLUE. PLAY OF COLOR THE FLASHING RAINBOW-LIKE COLORS IN OPAL THAT FLASH AT YOU AS YOU TURN THE STONE OR MOVE AROUND IT. -

Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina by W

.'.' .., Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie RUTILE GUMMITE IN GARNET RUBY CORUNDUM GOLD TORBERNITE GARNET IN MICA ANATASE RUTILE AJTUNITE AND TORBERNITE THULITE AND PYRITE MONAZITE EMERALD CUPRITE SMOKY QUARTZ ZIRCON TORBERNITE ~/ UBRAR'l USE ONLV ,~O NOT REMOVE. fROM LIBRARY N. C. GEOLOGICAL SUHVEY Information Circular 24 Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie Raleigh 1978 Second Printing 1980. Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: North CarOlina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development Geological Survey Section P. O. Box 27687 ~ Raleigh. N. C. 27611 1823 --~- GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SECTION The Geological Survey Section shall, by law"...make such exami nation, survey, and mapping of the geology, mineralogy, and topo graphy of the state, including their industrial and economic utilization as it may consider necessary." In carrying out its duties under this law, the section promotes the wise conservation and use of mineral resources by industry, commerce, agriculture, and other governmental agencies for the general welfare of the citizens of North Carolina. The Section conducts a number of basic and applied research projects in environmental resource planning, mineral resource explora tion, mineral statistics, and systematic geologic mapping. Services constitute a major portion ofthe Sections's activities and include identi fying rock and mineral samples submitted by the citizens of the state and providing consulting services and specially prepared reports to other agencies that require geological information. The Geological Survey Section publishes results of research in a series of Bulletins, Economic Papers, Information Circulars, Educa tional Series, Geologic Maps, and Special Publications. -

The Origins of Color in Minerals Four Distinct Physical Theories

American Mineralogist, Volume 63. pages 219-229, 1978 The origins of color in minerals KURT NASSAU Bell Laboratories Murray Hill, New Jersey 07974 Abstract Four formalisms are outlined. Crystal field theory explains the color as well as the fluores- cence in transition-metal-containing minerals such as azurite and ruby. The trap concept, as part of crystal field theory, explains the varying stability of electron and hole color centers with respect to light or heat bleaching, as well as phenomena such as thermoluminescence. The molecular orbital formalism explains the color of charge transfer minerals such as blue sapphire and crocoite involving metals, as well as the nonmetal-involving colors in lazurite, graphite and organically colored minerals. Band theory explains the colors of metallic minerals; the color range black-red-orange- yellow-colorless in minerals such as galena, proustite, greenockite, diamond, as well as the impurity-caused yellow and blue colors in diamond. Lastly, there are the well-known pseudo- chromatic colors explained by physical optics involving dispersion, scattering, interference, and diffraction. Introduction The approach here used is tutorial in nature and references are given for further reading or, in some Four distinct physical theories (formalisms) are instances, for specific examples. Color illustrations of required for complete coverage in the processes by some of the principles involved have been published which intrinsic constituents, impurities, defects, and in an earlier less technical version (Nassau, 1975a). specific structures produce the visual effects we desig- Specific examples are given where the cause of the nate as color. All four are necessary in that each color is reasonably well established, although reinter- provides insights which the others do not when ap- pretations continue to appear even in materials, such plied to specific situations. -

Beryllium Diffusion of Ruby and Sapphire John L

VOLUME XXXIX SUMMER 2003 Featuring: Beryllium Diffusion of Rubies and Sapphires Seven Rare Gem Diamonds THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE GEMOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA Summer 2003 VOLUME 39, NO. 2 EDITORIAL _____________ 83 “Disclose or Be Disclosed” William E. Boyajian FEATURE ARTICLE _____________ pg. 130 84 Beryllium Diffusion of Ruby and Sapphire John L. Emmett, Kenneth Scarratt, Shane F. McClure, Thomas Moses, Troy R. Douthit, Richard Hughes, Steven Novak, James E. Shigley, Wuyi Wang, Owen Bordelon, and Robert E. Kane An in-depth report on the process and characteristics of beryllium diffusion into corundum. Examination of hundreds of Be-diffused sapphires revealed that, in many instances, standard gemological tests can help identify these treated corundums. NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES _______ 136 An Important Exhibition of Seven Rare Gem Diamonds John M. King and James E. Shigley A look at the background and some gemological observations of seven important diamonds on display at the Smithsonian Institution from June to September 2003, in an exhibit titled “The Splendor of Diamonds.” pg. 137 REGULAR FEATURES _____________________ 144 Lab Notes • Vanadium-bearing chrysoberyl • Brown-yellow diamonds with an “amber center” • Color-change grossular-andradite from Mali • Glass imitation of tsavorite • Glass “planetarium” • Guatemalan jade with lawsonite inclusions • Chatoyant play-of-color opal • Imitation pearls with iridescent appearance • Sapphire/synthetic color-change sapphire doublets • Unusual “red” spinel • Diffusion-treated tanzanite? -

ZD525 Jeweller (Nov 2014)

Nov/Dec 2014 / Volume 23 / No. 9 Gem-A Conference 2014 Photo Competition Winners Mischievous emeralds Gems&Jewellery / Nov/Dec 2014 t Editorial Gems&Jewellery You know that feeling on Christmas Day — around 4pm after the Queen’s speech — when you think to yourself: “Well that’s it over for another year”? That’s perhaps how we are feeling here in Nov/Dec 14 Ely Place right now, coming down off the high of our conference. It takes a great deal of time, hard work and effort from the entire team to make it possible, and those of you who attended will agree that it was a resounding success. If you didn’t, you missed out on some fantastic speakers. We Contents are wondering now how to top it next year. See page 6 for Gary Roskin’s report on the conference. My thanks go to the Gem-A team and the speakers for a fun (and educational!) weekend. Gem News 4 At the meeting recently at the Foreign Office I was reminded that most people who work in the gem and jewellery industry are part of what was described as the ‘silent majority’. They are there, Gem-A Events 5 frequently seen but rarely heard. Often they lack representation or, if not, are merely part of a large number who are either swamped by the dollars of the big boys who shout louder or they just go with the flow, often unaware of the changes going on around them. The recent hiatus at the World Diamond Council (WDC) highlights this. -

OCTOBER 2017 GNEISS TIMES Wickenburg Gem & Mineral Society, Inc

VOLUME 49, Issue 7 OCTOBER 2017 GNEISS TIMES Wickenburg Gem & Mineral Society, Inc. P.O. Box 20375, Wickenburg, Arizona, 85358 E-Mail — [email protected] www.wickenburggms.org The purpose of this organization shall be to educate and to provide fellowship for people interested in rocks and minerals; to foster love and appreciation of minerals, rocks, gems, and the Earth. Membership shall be open to all interested people. CAUSES OF COLOR IN MINERALS Color is probably the first thing we notice when we see a mineral specimen. But what causes those colors and their variations? We often simply say A graduate of Wickenburg High School, Everett is that the presence of a particular element (either attending Estrella Community College, and will integral to the mineral’s composition, or as in transfer to ASU in the future. impurity) imparts a particular color. And basically that is true, however……... ELECTIONS COMING -- In fact, Beryl, Quartz, and Tourmaline are examples DUTIES OF CLUB OFFICERS of minerals that would be clear, if not for impurities. The club will be holding election of officers in December. The nominating committee will be But technically, color is caused by the absorption of preparing a ballot of nominees. Several of these wavelengths of visible light*, so that the light positions are open. Anyone willing to fill an opening reflected back to our eyes is deficient in the please contact Craig or Debbie. The vitality of our wavelength absorbed. There are five main club is dependent on the participation of the categories under which this occurs: metal ions in members! The club was founded in the early 1970’s the chemical formula or as impurity, intervalence and the current membership is 127. -

Mohsen Manutchehr-Danai Dictionary of Gems and Gemology Mohsen Manutchehr-Danai

Mohsen Manutchehr-Danai Dictionary of Gems and Gemology Mohsen Manutchehr-Danai Dictionary of Gems and Gemology 2nd extended and revised edition With approx. 25 000 entries, 1 500 figures and 42 tables Author Professor Dr. Mohsen Manutchehr-Danai Dr. Johann-Maier-Straße 1 93049 Regensburg Germany Library of Congress Control Number: 2004116870 ISBN 3-540-23970-7 Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitations, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplica- tion of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copy- right Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be ob- tained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer is a part of Springer Science+Business Media springeronline.com © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2005 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: Erich Kirchner, Heidelberg Typesetting: Camera ready by the author Production: Luisa Tonarelli Printing and binding: Stürtz, Würzburg Printed on acid-free paper 30/2132/LT – 5 4 3 2 1 0 Preface to the Second Edition The worldwide acceptance of the first edition of this book encouraged me to exten- sively revise and extend the second edition. -

Rendering Precious Gems

RENDERING PRECIOUS AND SEMI-PRECIOUS GEMS PERSONAL REASONING Part of the research for my thesis – Glyptics Portrait Generator Glyptics is the art of producing engraved gems This seminar is the research of gemstone properties Roman Emperor Caracalla engraved in amethyst WHAT IS A GEM? A precious stone of any kind, esp. when cut and polished for ornament; a jewel. CLASSIFICATION Gemstones Precious Semi-precious CLASSIFICATION Precious only 4 gems Can you name them? CLASSIFICATION Precious only 4 gems • Emerald • Ruby • Sapphire • Diamond CLASSIFICATION • Agate Semi-precious • Alexandrite too many to list all of them here • Amethyst • Ametrine • Apatite • Aquamarine • Aventurine • Azurite… And those are not even all the gems, starting with an “A” GENERAL PROPERTIES GENERAL PROPERTIES • Refraction and sometimes birefringence • Produces dichroism (multi-coloring) and doubling GENERAL PROPERTIES • Refraction and sometimes birefringence • Internal reflections • Produce brilliance – light, reflected from the inside GENERAL PROPERTIES • Refraction and sometimes birefringence • Internal reflections • Dispersion • Produces fire – splitting light into colors of the spectrum GEMSTONE CUTTING Improper cutting affects internal reflectiveness => brilliance REFRACTIVE INDEX • Different gems have different refractive indices • In case of birefringence, gems have two refractive indices • Higher RI means higher brilliance • Diamond has a RI of 2.42, while ruby has 1.76 Refractometer – device for measuring refractive index SO… HOW TO RENDER THAT? SO… HOW TO -

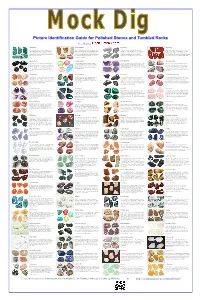

Picture Identification Guide for Polished Stones and Tumbled Rocks Provided By

Picture Identification Guide for Polished Stones and Tumbled Rocks Provided by Amazonite Coral, Agatized Lepidolite Red Jasper Amazonite is a green microcline feldspar. It is A rare find is fossil coral that has been replaced by Lepidolite is a variety of mica that occurs in a Jasper is an opaque chalcedony and red is one of its named after the Amazon River of South America, agate - or agatized. This type of fossilization often spectrum of colors that range from pink to deep most common colors. This red jasper from South where the first commercial deposits were found. preserves the structure of the coral individual or lavender. The stones shown here are tumbled Africa has a fire-engine red color that in some The stones shown here are a rich green Amazonite colony. The result can be a beautiful stone that can quartz pebbles that have enough lepidolite stones is interrupted by a white to transparent quartz that was mined in Russia. be polished to display cross and lateral sections inclusions to yield pink and lavender gemstones. vein. It often accepts an exceptionally high polish. through the coral fossil. Apache Tears Crackle Quartz Lilac Amethyst Rhodonite - Pink Apache Tears are round nodules of obsidian that "Crackle Quartz" is a name used for quartz Amethyst is a purple variety of crystalline quartz that Rhodonite is a metamorphic manganese mineral can be transparent through translucent. When it has polish to a beautiful jet black color. If you hold them specimens that have been heat treated and then that is well known for its beautiful pink color. -

Fundamental of Physical Geography Chapter-5 Minerals and Rocks This

Fundamental of Physical Geography Chapter-5 Minerals and Rocks This unit deals with : Minerals, elements, characteristics of minerals such as crystal form cleavage, fracture, lustre, important minerals such as feldspar, quartz, pyroxene, colour, streak, transparency, structure, hardness specific grvity, amphibole, mica, olivine and their characteristics classification of minerals, rocks, igneous, sedimentary, metamorphic rocks rock cycle Minerals found in the crust are in solid form where as in intrior they are in liquid form 98% of the crust consist of eight elements 1. oxygen 2. Aluminium 3. Sodium 4. Potassium 5. Iron. 6. Calcium 7. Magnes the rest is constituted by titanium, hydrogen, phosphorous, manganese, sulphur carbon, nickel & other elements Table 5.1: The major Elements of the Earth’s Crust Sl. No. Elements By Weight(%) 1. Oxygen 46.60 2. Silicon 27.72 3. Aluminium 8.13 4. Iron 5.00 5. Calcium 3.36 6. Sodium 2.83 7. Potassium 2.59 8. Magnesium 2.09 9. Others 1.4 Minerals: The elements in the earth’s crust are rarely found exclusively but are usually combined with other elements to make various substances. These substances are recognised as minerals. Minerals are substances that are formed naturally in the Earth. Minerals are usually solid, have a crystal structure, inorganic and form naturally by geological processes. The study of minerals is called mineralogy. A mineral can be made of single chemical element or more usually a compound. Naturally occuring inorganic substance having an orderly atomic structure and a definite chemical composition and physical properties. It is composed of two or three minerals /single element ex. -

The Gemstone Book

© CIBJO 2020 All rights reserved GEMSTONE COMMISSION 2020 - 1 2020-1 2020-12-1 CIBJO/Coloured Stone Commission The Gemstone Book CIBJO standard E © CIBJO 2020. All rights reserved COLOURED STONE COMMISSION 2020-1 Foreword .................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................... vi 1. Scope ................................................................................................................................. 8 2. Normative references .......................................................................................................... 8 3. Classification of materials .................................................................................................... 9 3.1. Natural materials ........................................................................................................... 9 Only materials that have been formed completely by nature without human interference/intervention qualify as “natural” within this standard. ........................................... 9 3.1.1. Gemstones ................................................................................................................................... 9 3.2. Artificial products ........................................................................................................... 9 3.2.1. Artificial products with gemstone components -

Physics and Chemistry of Gemstone Colour and Clarity Enhancement

CHAPTER - 3 COLOUR IN GEMSTONE Gemstone’s colour depends on the light. Without light, there is no colour. Gemstone colour is a result of absorption and reflection of visible light. When white visible light passes through a gemstone some of energy is reflected and some of the energy of the white light is absorbed in gemstone which caused colour in Gemstone. Fig. 3.1 Origin of colour in gemstone where some of the light absorb and some of the light reflect. Gemstone colour is divided into three categories which are depended on the chemical composition of the gemstones, impurity available in the host and false colour. The colour of the gemstone is classified as Idiochromatic, Allochromatic and Pesudochromatic. The Idiochromatic colour means colours formed due to its original chemical composition. The Allochromatic colour means colour formed as a result of presence of impurity available in the gemstone. And the Pesudochromatic colour means colour originated from optical effect. The causes of color can be divided into four theories: 1. The Crystal Field Theory 2. The Molecular Orbital Theory 3. The Band Theory 4. The Physical Properties Theory THE CRYSTAL FIELD THEORY According to Crystal field theory, colors of gemstone is originating from the excitation of electrons in transition elements and color centers. When a transition metal ion has a partially filled d-shell, the electrons in the outer d-shell orbit the nucleus unpaired. The surrounding ions of the crystal lattice create a force which is known as a "crystal field" and it forms around such a transition element and the 16 strength of those fields determine which energy levels are available for the unpaired electrons.