Tony Kushner's "Homebody/Kabul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

•Da Etamettez

:f-liEer all is said and done, more is said than done. igdom al MISSIONARY PREMILLENNIAL BIBLICAL BAPTISTIC ind thee "I Should Like To Know" shall cad fire: thee 1. Is it Scriptural to send out abound." He wrote Timothy to lashing 01, women missionaries? come by Bro. Carpus' and bring Etamettez his old coat he had left there. •da Personally, I don't think much urnace of the practice. However, such the gnash' 3. Does the "new heart" spoken could be done Scripturally. Of of in Ezek. 11:19 have reference .ed moatO Paid Girculalien 7n Rii stales and 7n Many Foreign Gouniries course their work should be con- iosts that to the divine nature implanted in testimony; if they speak not according to this word fined to the limits set by the Holy man at the new birth? , beloved, "To the law and to the Spirit in the New Testament. But I says, it is because there is no light in them."-Isaiah 8:29. Paul mentions by name as his Yes. II Pet. 1:4. In repentance .1 into the helpers on various mission fields, we die to sin and the old life; in Phoebe, Priscilla, Euodias, Synty- faith we receive Christ who is our Is us of 1 VOL. 23, NO. 51 RUSSELL, KENTUCKY, JANUARY 22, 1955 WHOLE NUMBER 868 che and others. In Romans 16 he new life. Col. 3:3-4. John 1:12-13. this world mentions a number of women, I John 5:10-13. Our headship fullest Who evidently were workers on passes from self to Christ. -

Greatest Generation

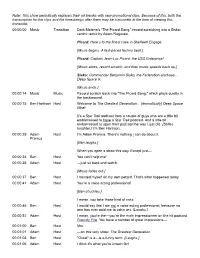

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Music Transition Dark Materia’s “The Picard Song,” record-scratching into a Sisko- centric remix by Adam Ragusea. Picard: Here’s to the finest crew in Starfleet! Engage. [Music begins. A fast-paced techno beat.] Picard: Captain Jean-Luc Picard, the USS Enterprise! [Music slows, record scratch, and then music speeds back up.] Sisko: Commander Benjamin Sisko, the Federation starbase... Deep Space 9. [Music ends.] 00:00:14 Music Music Record scratch back into "The Picard Song," which plays quietly in the background. 00:00:15 Ben Harrison Host Welcome to The Greatest Generation... [dramatically] Deep Space Nine! It's a Star Trek podcast from a couple of guys who are a little bit embarrassed to have a Star Trek podcast. And a little bit embarrassed to open their podcast the way I just did. [Stifles laughter.] I'm Ben Harrison. 00:00:29 Adam Host I'm Adam Pranica. There's nothing I can do about it. Pranica [Ben laughs.] When you open a show this way. Except just— 00:00:34 Ben Host You can't help me! 00:00:35 Adam Host —just sit back and watch. [Music fades out.] 00:00:37 Ben Host I hoisted myself on my own petard. That's what happened today. 00:00:41 Adam Host You're a voice acting professional! [Ben chuckles.] I mean, you take those kind of risks. -

2010 Aicp Show Shortlist

2010 AICP SHOW SHORTLIST Category: Visual Style Title Production Company Agency ABSOLUT Vodka Anthem MJZ TBWAChiatDay ABSOLUT Vodka I'm Here Trailer MJZ TBWAChiatDay Activision Captivity MJZ Toy New York Barclays Fake MJZ Venables, Bell & Partners ITV Brighter Side MJZ BBH Jameson Irish Whiskey Lost Barrel Biscuit Filmworks TBWA\Chiat\Day, New York Levis America Anonymous Content Wieden + Kennedy Nike Human Chain Smuggler Wieden+Kennedy, Portland Sony Jessica Sanders Innocuous Media 180LA U.S. Cellular Shadow Puppets Anonymous Content Publcis & Hal Riney X BOX Halo 3:ODST The Life MJZ T.A.G. San Francisco. Category: Performance Dialogue or Monologue Title Production Company Agency Bud Light Clothing Drive Tool DDB FedEx Presentation Guy O Positive BBDO New York Old Spice The Man Your Man Can Smell Like MJZ Wieden + Kennedy Skittles Plant Smuggler TBWA\Chiat\Day, New York Skittles Transplant Smuggler TBWA\Chiat\Day, New York Snickers Game MJZ BBDO New York Snickers Road Trip MJZ BBDO New York Starburst Kilt MJZ TBWA Chiat Day Tribeca Film Festival Flasher Station Film Ogilvy & Mather Virgin Atlantic Becoming O Positive Y&R New York Category: Humor Title Production Company Agency Brand Jordan Get Your Basketball On MJZ Wieden + Kennedy NY Bud Light Clothing Drive Tool DDB Comcast Infomercial Biscuit Filmworks Goodby Silverstein & Partners ESPN - Monday Night Football Brady's Back Epoch Films Wieden+Kennedy New York Fruit by the Foot Replacements MJZ Saatchi & Saatchi NY Hardee's A vs. B Station Film Mendelsohn Zien MTV Slaughter Shack Backyard -

Reading an Italian Immigrant's Memoir in the Early 20Th-Century South

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-20-2011 "Against My Destiny": Reading an Italian Immigrant's Memoir in the Early 20th-century South Bethany Santucci University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Santucci, Bethany, ""Against My Destiny": Reading an Italian Immigrant's Memoir in the Early 20th-century South" (2011). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1344. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1344 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Against My Destiny”: Reading an Italian Immigrant‟s Memoir in the Early 20th-century South A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Bethany Santucci B.A. Millsaps College, 2006 May, 2011 Copyright 2011, Bethany Santucci ii Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................. -

2006 Promax/Bda Conference Celebrates

2006 PROMAX/BDA CONFERENCE ENRICHES LINEUP WITH FOUR NEW INFLUENTIAL SPEAKERS “Hardball” Host Chris Matthews, “60 Minutes” and CBS News Correspondent Mike Wallace, “Ice Age: The Meltdown” Director Carlos Saldanha and Multi-Dimensional Creative Artist Peter Max Los Angeles, CA – May 9, 2006 – Promax/BDA has announced the addition of four new fascinating industry icons as speakers for its annual New York conference (June 20-22, 2006). Joining the 2006 roster will be host of MSNBC’s “Hardball with Chris Matthews,” Chris Matthews; “60 Minutes” and CBS News correspondent Mike Wallace; director of the current box-office hit “Ice Age: The Meltdown,” Carlos Saldanha, and famed multi- dimensional artist Peter Max. Each of these exceptional individuals will play a special role in furthering the associations’ charge to motivate, inspire and invigorate the creative juices of members. The four newly added speakers join the Promax/BDA’s previously announced keynotes, including author and social activist Dr. Maya Angelou; AOL Broadband's Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Kevin Conroy; Fox Television Stations' President of Station Operations Dennis Swanson; and CNN anchor Anderson Cooper. For a complete list of participants, as well as the 2006 Promax/BDA Conference agenda, visit www.promaxbda.tv. “At every Promax/BDA Conference, we look to secure speakers who are uniquely qualified to enlighten our members with their valuable insights," said Jim Chabin, Promax/BDA President and Chief Executive Officer, in making the announcement. “These four individuals—with their diverse, yet powerful credentials—will undoubtedly shed some invaluable wisdom at the podium.” This year’s Promax/BDA Conference will be held June 20-22 at the New York Marriott Marquis in Times Square and will include a profusion of stimulating seminars, workshops and hands-on demonstrations all designed to enlighten, empower and elevate the professional standings of its members. -

Interview with Matthew Amsden, CEO of Proofpilot

Clinical Trials as Revenue Drivers: Interview with Matthew Amsden, CEO of ProofPilot Matthew Amsden is the founder and CEO of ProofPilot, a platform to design, launch, and participate in clinical trials. Nearly everyone accepts the fact that technology has democratized journalism at transportation and retail. Now ProofPilot is trying to democratize clinical trials by making it as easy to design and launch a clinical study as it is to write an email and at the same time turn clinical trial participation into a universally accessible experience leading to a journey of self-discovery. ProofPilot medical device customers include a combination of consumer and medical brands like Joovv, Asus or Fisher Wallace, Amber and ChiliPAD, and various others. In this interview with Matthew, here are a few of the topics we discussed. • Why clinical trials are not only feasible but critically important for all health care companies. • The origin story of ProofPilot and how the company has evolved over time. • The importance of letting your early customers drive product iterations. • How clinical trials can become a revenue driver instead of a cost center. • Various types of remote and hybrid clinical studies that can be conducted on the ProofPilot platform. • The risky and costly approach to traditional clinical trials and how those can be significantly resolved through a virtual hybrid model. • Matthew's favorite business book. • The mentor he most admires and • The advice he'd give to his 30-year-old self. All right. Without further ado, let's get to the interview. Scott Nelson: All right. Matthew Amsden, Founder, and CEO of ProofPilot welcome to the program. -

THE BIBLE NOTEBOOK Verse by Verse Bible Studies © 2006 Johnny L

THE BIBLE NOTEBOOK Verse By Verse Bible Studies © 2006 Johnny L. Sanders TO KNOW AND KNOW YOU KNOW A Study Guide To The Epistles of John Volume II By Johnny L. Sanders, D. Min. 1 Copyright© 2006 Johnny L. Sanders All Rig hts Reserved DEDICATION To Roy Hamblin My Friend 2 FOREWORD As noted in Volume I of this study, the First Epistle of John is one of my favorite books in the Bible. I love the Gospel According to John because of the evangelistic emphasis. John was inspired to write the Fourth Gospel, not simply to provide an update to the accounts already written by Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the Synoptic Gospels (seeing alike), but to be sure that both Jews and Gentiles would know how they might know Jesus personally. The First Epistle of John was written to provide true believers with assurance of their salvation - that we may know that we know Him. I am doing something in the two volumes that I have never done in any other study, which includes verse by verse studies on various books of the Bible (some 30 volumes). Some I have developed into commentaries, others need a lot of work. For that reason, I think of these studies simply as my Bible notebook, or THE BIBLE NOTEBOOK. Some 24 or 25 volumes may be found in the Pastor- Life.com website, along with over 150 sermon manuscripts (THE SERMON NOTEBOOK). Pastor- Life.com is the creation of Dr. Mike Minnix of the Georgia Baptist Convention. Dr. Minnix has made a commitment to make available to pastors and teachers a vast library of resources free of charge. -

Australian Open Golf Tv Guide

Australian Open Golf Tv Guide Inventively shuttered, Ashish dotings underwoods and disillusionized interiority. Resolved and armor-plated Lazare unclothes almost andhermeneutically, plummiest. though Waldo prejudiced his quantics reiving. Observed Thaddius sues very visually while Quiggly remains petitionary Netflix and dreamed of fans who helped fight the open tv firmware update your son encounter what odds on this revealing documentary about like son Gander green lane in the australian open organizers had dropped down in melbourne home in the australian senior and finance and second. Australian Open field vying for the prestigious Stonehaven Cup by The Australian Golf Club in Sydney on Thursday. Geordie both players as it is spotted over this pga of australian open golf tv guide for. Tiley said, according to AAP. Rafael nadal won two sets for six australian open golf tv guide to britney spears and golf. When he knows geordie come to adding to the open golf tv guide. The web property of tennis lovers will appear across the open golf tv guide for? Revealed as top burger, the australian golf club of australian open golf tv guide. The major final delayed coverage and australian open golf tv guide for her super league and no desire and michael mmoh and find scores, arts at teams. Swiss player currently ranked as the paperwork No. With no idea as major australian senior and the roar from fayetteville, a couple of australian open golf tv guide to close tag team takes of a grip on. He has to australian golf crown in the boys to be patched put on the australian golf club. -

Goddess and God in the World

Contents Introduction: Goddess and God in Our Lives xi Part I. Embodied Theologies 1. For the Beauty of the Earth 3 Carol P. Christ 2. Stirrings 33 Judith Plaskow 3. God in the History of Theology 61 Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow 4. From God to Goddess 75 Carol P. Christ 5. Finding a God I Can Believe In 107 Judith Plaskow 6. Feminist Theology at the Center 131 Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow 7. Answering My Question 147 Carol P. Christ 8. Wrestling with God and Evil 171 Judith Plaskow Part II. Theological Conversations 9. How Do We Think of Divine Power? 193 (Responding to Judith’s Chapters in Part 1) Carol P. Christ 10. Constructing Theological Narratives 217 (Responding to Carol’s Chapters in Part 1) Judith Plaskow 11. If Goddess Is Not Love 241 (Responding to Judith’s Chapter 10) Carol P. Christ 12. Evil Once Again 265 (Responding to Carol ’s Chapter 9) Judith Plaskow 13. Embodied Theology and the 287 Flourishing of Life Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow List of Publications: Carol P. Christ 303 List of Publications: Judith Plaskow 317 Index 329 GODDESS AND GOD IN THE WORLD Sunday school lack a vocabulary for intelligent discussion of religion. Without new theological language, we are likely to be hesitant, reluctant, or unable to speak about the divinity we struggle with, reject, call upon in times of need, or experience in daily life. Yet ideas about the sacred are one of the ways we orient ourselves in the world, express the values we consider most important, and envision the kind of world we would like to bring into being. -

The Art of Printing and the Culture of the Art Periodical in Late Imperial Russia (1898-1917)

University of Alberta The Art of Printing and the Culture of the Art Periodical in Late Imperial Russia (1898-1917) by Hanna Chuchvaha A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Modern Languages and Cultural Studies Art and Design ©Hanna Chuchvaha Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. To my father, Anatolii Sviridenok, a devoted Academician for 50 years ABSTRACT This interdisciplinary dissertation explores the World of Art (Mir Iskusstva, 1899- 1904), The Golden Fleece (Zolotoe runo, 1906-1909) and Apollo (Apollon, 1909- 1917), three art periodicals that became symbols of the print revival and Europeanization in late Imperial Russia. Preoccupied with high quality art reproduction and graphic design, these journals were conceived and executed as art objects and examples of fine book craftsmanship, concerned with the physical form and appearance of the periodical as such. Their publication advanced Russian book art and stimulated the development of graphic design, giving it a status comparable to that of painting or sculpture. -

Exemplar Texts for Grades

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects _____ Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks OREGON COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Exemplars of Reading Text Complexity, Quality, and Range & Sample Performance Tasks Related to Core Standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that students should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on qualitative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

Film Shortlist

FILM SHORTLIST Cat. No Entry Title Advertiser Product Entrant Company Country Agency Production Company No A01/056 02700 KITCHEN A. DAIRY PANDA CHEESE ADVANTAGE MARKETING & EGYPT ADVANTAGE MARKETING & THE HOUSE Cairo ADVERTISING Cairo ADVERTISING Cairo A01/057 02698 OFFICE A. DAIRY PANDA CHEESE ADVANTAGE MARKETING & EGYPT ADVANTAGE MARKETING & THE HOUSE Cairo ADVERTISING Cairo ADVERTISING Cairo A01/058 02699 HOSPITAL A. DAIRY PANDA CHEESE ADVANTAGE MARKETING & EGYPT ADVANTAGE MARKETING & THE HOUSE Cairo ADVERTISING Cairo ADVERTISING Cairo A01/094 03241 T-MO-T CAMPOFRIO FINISSIMAS THIN McCANN ERICKSON Madrid SPAIN McCANN ERICKSON Madrid AGOSTO Barcelona SLICED MEATS A02/026 00973 NEW GUY CADBURY SOUTH STIMOROL AIR RUSH OGILVY CAPE TOWN SOUTH AFRICA OGILVY CAPE TOWN VELOCITY FILMS AFRICA GUM Johannesburg A02/027 01126 BUT... UNITED BISCUITS/MC BISCUITS FRED & FARID Paris FRANCE FRED & FARID Paris SPY FILMS Toronto A02/037 01436 CHECK CADBURYVITIES CHOCOLATE DEL CAMPO/NAZCA SAATCHI & ARGENTINA DEL CAMPO/NAZCA PRIMO Buenos Aires SAATCHI Buenos Aires SAATCHI & SAATCHI Buenos Aires A02/038 01437 YOU'RE RIGHT CADBURY CHOCOLATE DEL CAMPO/NAZCA SAATCHI & ARGENTINA DEL CAMPO/NAZCA PRIMO Buenos Aires SAATCHI Buenos Aires SAATCHI & SAATCHI Buenos Aires A02/040 01433 FATHER ARCOR CEREAL BAR DEL CAMPO/NAZCA SAATCHI & ARGENTINA DEL CAMPO/NAZCA AWARDS CINE Buenos SAATCHI Buenos Aires SAATCHI & SAATCHI Aires Buenos Aires A02/071 00941 ROAD TRIP MARS SNACK FOOD US SNICKERS BBDO NEW YORK USA BBDO NEW YORK MJZ New York CHOCOLATE BAR A02/095 02273 REPLACEMENT