Ombudsman Victoria Annual Report 06 Ordered to Be Printed Victorian Government Printer Session 2003 – 2006 P.P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2022 Australian Open Tennis Tournament

THE 2022 AUSTRALIAN OPEN TENNIS TOURNAMENT January 17 - 30 Extended Early Rounds Tour Packages include: • Jan. 16 – 21, five nights’ accommodations at the Crown Promenade Hotel (Standard Room), with full breakfast daily • Access to the on-site private hospitality space, which features light hors d'oeuvres and two complimentary drink vouchers, as well as the Atrium Lounge for all sessions of tennis • Complete Traveler's Information Portfolio • 5 sessions of tennis on Rod Laver Arena in Reserved Category One seats in the shade, within the first 10 rows (see seat chart next page): Mon January 17th Day Session 11:00 AM Men's & Women's 1st Round VIP Category One Courtside Seats Rod Laver Arena Mon January 17th Evening Session 7:00 PM Men's & Women's 1st Round VIP Category One Courtside Seats Rod Laver Arena Tue January 18th Day Session 11:00 AM Men's & Women's 1st Round VIP Category One Courtside Seats Rod Laver Arena Wed January 19th Day Session 11:00 AM Men's & Women's 2nd Round VIP Category One Courtside Seats Rod Laver Arena Wed January 19th Evening Session 7:00 PM Men's & Women's 2nd Round VIP Category One Courtside Seats Rod Laver Arena $4795 per person, double occupancy The Crown Promenade is a stylish, modern four-star hotel located in Southbank Melbourne that offers spacious rooms with views of Port Phillip Bay or the city and Yarra River. With its location in Melbourne's vibrant Southbank entertainment precinct, Crown Promenade is directly linked to the Crown Casino and Entertainment Complex, offering world-class restaurants, bars and shopping. -

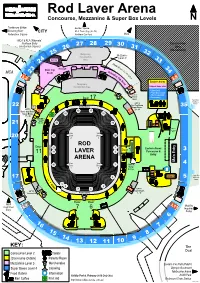

RLA Multi V1

Rod Laver Arena Concourse, Mezzanine & Super Box Levels N Tanderrum Bridge Garden Square Birrarung Marr CITY RLA Tram Stop (No.70) Federation Square Northern Car Park MCG MCA & RLA 'Alternate' Northern Entry 27 28 29 30 Construction (via Garden Square) 26 31 Area 32 (Unavailable) 25 Temporary Mezzanine 9 Construction (Level 3) 33 Balcony 5 BalconyArea LIFT 24 Ramp Annexe Access 34 The Loft Davis Cup to Fed concourse MCA 23 Room era tion L2 Cup Room L5 5 Emergency Eastern Annex LIFT Temporary5 Exit L2 Construction Area Railyards Bistro & Bar L5 · Upper Deck · Super Box Lounge Access to · The Racquet Club M Annex via Level 3 · Observatory Door 17 Skywalk Super Box Access to LIFT 5 Annex 22 Fed Cup Room 35 L8 Arena Doors Super Boxes LIFT 2 L2 29 - 35 Davis Cup Room 16 17 L5 Super Boxes 15 18 17 - 28 STAIRS 2 Davis Cup Room L6 21 M (The Loft) 14 19 L7 L8 Outdoor Seating Escalator Area Vom Vom 13 Door Door 20 20 2 3 ROD Arena Doors Door 12 1 Door Eastern Annex 3 11 11 LAVER 2 1 Concourse & Arena Doors Entry ARENA RAMP Main Entry Vom Vom 4 10 Door Door 3 Stairs & Ramp 1 4 Access ATM L9 L10 TICKETS Super Box 17 4 5 Access to Annex RAMP 9 8 5 L11 7 6 LIFT 11 LIFT 1 L1 Super Boxes RAMP Arena Doors 3 - 16 Service Lift M M Door Door MCA L11 ATM Mobility South East L1 7 6 Impaired Entry Ramp 6 16 7 15 8 14 9 13 12 11 10 KEY: The Oval Concourse Level 2 Toilets (Concourse Outlets) Parents Room Mezzanine Level 3 M Merchandise Eastern Car Park (Public) Super Boxes Level 4 Cloaking Olympic Boulevard Melbourne Arena Food Outlets Information Validity Period. -

Australian Open Packages 15-28 January 2018 | Melbourne Australia

2018 AUSTRALIAN OPEN PACKAGES 15-28 JANUARY 2018 | MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRALIAN OPEN 2018 ASTSPORTS.COM.AU | 1800 026 668 AUSTRALIAN SPORTS TOURS AUSTRALIAN OPEN OFFICIAL TOUR OPERATOR Australian Sports Tours has been an off icially We off er a full range of accommodation to suit licensed tour operator for the Australian Open all budgets including 3 star, 4 star and 5 star since 2007. hotels. Each of our hotels are ideally located in Melbourne’s CBD and are just a short walk When you purchase your package through us, you or complimentary tram ride away from all the can rest easy knowing that your tickets are 100% excitement and action at the fabulous Melbourne guaranteed by Tennis Australia. Park tennis and entertainment precinct. Our packages all come with reserved seating on We look forward to providing you with the ultimate Rod Laver Arena with the choice of Category 1, Grand Slam® tennis experience in 2018! Category 2 & Category 3 seating. The Team at For those looking for even more from their Aus Australian Sports Tours Open experience, we also have access to a full range of hospitality services within the Melbourne Park precinct including casual dining right through to silver service. ASTSPORTS.COM.AU | 1800 026 668 AUSTRALIAN OPEN 2018 2 Australian Open 2017 N Door number Corporate seating Shade Restricted viewing seats ROD LAVER ARENA TICKETS PP323 PP343 PP359 PP379 PP301 PP401 65 30 31 The tickets included in our packages are Category PP280 64 32 63 33 PP422 3 Upper Level seating. You will also have the AA326 AA343 AA359 AA381 option to upgrade to Lower Level Category 2 or PP260 AA301 62 10 11 AA401 Lower Level Category 1 seating along with several U212 U227 34 AA280 9 U195 U243 12 PP442 AA422 hospitality options. -

Still on the Road 2018 Far East & Down Under Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 2018 FAR EAST & DOWN UNDER TOUR JULY 27 Seoul, South Korea Olympic Gymnastics Arena 29 Yuzawa-cho, Niigata, Japan Fuji Rock Festival '18 - Naeba Ski Resort AUGUST 2 Taipei, Taiwan International Convention Center 4 Hong Kong, China Hong Kong Convention & Exhibition Centre 6 Singapore, Singapore Star Theatre, Star Performing Arts Centre 8 Perth, West Australia, Australia Perth Arena 11 Adelaide, South Australia, Australia Bonython Park 13 Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Margaret Court Arena 14 Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Margaret Court Arena 18 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia ICC Sydney Theatre 19 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Enmore Theatre 20 Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia WIN Entertainment Centre 22 Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia Newcastle Entertainment Centre 24 Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Brisbane Entertainment Centre 26 Auckland, New Zealand Spark Arena 28 Christchurch, New Zealand Horncastle Arena Far East stops Bob Dylan: Still On The Road 2018 Far East & Down Under Tour Bob Dylan: Still On The Road 2018 Far East & Down Under Tour 39160 Olympic Gymnastics Arena Seoul, South Korea 27 July 2018 1. All Along The Watchtower 2. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right 3. Highway 61 Revisited 4. Simple Twist Of Fate 5. Duquesne Whistle 6. When I Paint My Masterpiece 7. Honest With Me 8. Tryin' To Get To Heaven 9. Make You Feel My Love 10. Pay In Blood 11. Tangled Up In Blue 12. Early Roman Kings 13. Desolation Row 14. Love Sick 15. Autumn Leaves (Joseph Kosma, Johnny Mercer, Jacques Prevert) 16. Thunder On The Mountain 17. Soon After Midnight 18. -

Grand Slam Tennis Back at Melbourne Park

Monday, 8 February 2021 GRAND SLAM TENNIS BACK AT MELBOURNE PARK The Australian Open kicks off in Melbourne today, with strict public health directions in place across the Melbourne Park precinct to protect the efforts of Victorians to combat coronavirus. Minister for Tourism, Sport and Major Events Martin Pakula praised the ongoing work of Victorians to contain coronavirus, which has made it possible for the Grand Slam tournament to proceed. Melbourne Park is divided into three zones around Rod Laver Arena, Margaret Court Arena and John Cain Arena as part of rigorous infection prevention and control measures in place to ensure the safety of players, officials, and the broader Victorian community. Dedicated entry points will apply for each zone and no movement will be permitted between the zones. There will be a daily crowd capacity of 30,000 for the first eight days, with 25,000 per day from the quarter-finals and 12,500 in Rod Laver Arena for the final three days of the tournament. Over the two weeks of the event, this will equate to about half of the average attendance in the past three years. The Australian Open is a key pillar of Victoria’s major event program – last year it contributed an estimated $387 million to the state’s visitor economy. The Victorian Government has invested almost $1 billion over the past 10 years in upgrading and expanding Melbourne Park so that it can continue to host the Open until at least 2039. When completed in time for the 2023 Australian Open, the final stage in the Melbourne Park redevelopment will have created 2,300 full-time jobs through the Andrews Labor Government’s Local Jobs First Policy. -

Rod Laver Arena

1/12/2019 Match Schedule | Australian Open 14-01-2019 - Main Draw Day 1 Order of Play Rod Laver Arena Day session From 11:00am AEDT M. Sharapova (30) versus H. Dart (Q) Women's Singles 1st Round J. Duckworth (WC) versus R. Nadal (2) Men's Singles 1st Round P. Hercog versus A. Kerber (2) Women's Singles 1st Round Night session From 7:00pm AEDT A. Van Uytvanck versus C. Wozniacki (3) Women's Singles 1st Round D. Istomin versus R. Federer (3) Men's Singles 1st Round Margaret Court Arena Day session From 11:00am AEDT J. Goerges (14) versus D. Collins Women's Singles 1st Round S. Stephens (5) versus T. Townsend Women's Singles 1st Round Not before 3:00pm AEDT A. de Minaur (27) versus P. Sousa Men's Singles 1st Round Night session From 7:00pm AEDT A. Barty (15) versus L. Kumkhum Women's Singles 1st Round M. Cilic (6) versus B. Tomic Men's Singles 1st Round https://ausopen.com/schedule#!8006 1/6 1/12/2019 Match Schedule | Australian Open Melbourne Arena Day session From 11:00am AEDT K. Anderson (5) versus A. Mannarino Men's Singles 1st Round M. Sakkari versus J. Ostapenko (22) Women's Singles 1st Round K. Edmund (13) versus T. Berdych Men's Singles 1st Round Not before 6:00pm AEDT R. Bautista Agut (22) versus A. Murray Men's Singles 1st Round Not before 7:00pm AEDT P. Kvitova (8) versus M. Rybarikova Women's Singles 1st Round 1573 Arena Day session From 11:00am AEDT J. -

2014-15 State Budget Overview

Ideas to Outcomes COMMITTEE FOR MELBOURNE BRIEFING NOTE 2014-15 State Budget Overview Overview In his final budget address before the November 29th State election, Treasurer Michael O’Brien delivered an optimistic and healthy outlook for the Victorian economy, drawing reference to the fact that Victoria stands alone as the only jurisdiction in Australia to be operating a surplus over the next four years. As expected, central to the 2014-15 Budget was a $27 billion construction and infrastructure program, which intends to deliver jobs and maintain the liveability of the state. It is worth noting however that whilst the proposed investments in infrastructure are sizeable, spending allocations for the 2014-15 financial year remain limited with a large proportion of this spending either earmarked for later years or remaining unaccounted for. Table 1 – Summary of Key Infrastructure Asset Spending ($ million) Total Expected 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 Investment Melbourne Rail Link 40 50 140 600 8,500-11,000 East West Link – Western 100 650 1,100 1,350 8,000-10,000 Section Metro Level Crossing 76 242 340 1.6 659 Program* Note * Metro Level Crossing Program includes the three level crossing removals at Glen Iris, Ormond and Blackburn, as well as the level crossing removal at St Albans, which is being delivered as part of the Regional Rail Link project This subsequent member brief provides a summary of key highlights from the 2014-15 Victorian State Budget, addressing the most relevant issues to the Committee for Melbourne’s agenda. Economic Context For the 2014-15 Victorian State Budget, the Coalition Government has forecast a budget surplus of $ 1.3 billion. -

Margaret Court Arena in Melbourne

Margaret Court Arena in Melbourne Margaret Court Arena is the third largest venue for Australian open. The Margaret Court Arena is the third and latest addition to the Melbourne Park. It is the third largest venue for the Australian Open, after the Rod Laver Arena and the Hisense Arena. It is famous for its retractable roof that opens and closes in 5 minutes- the fastest retractable roof in the world. Just before the 2003 Australian Open, the Margaret Court Arena was renamed after the famous Australian woman player, Margaret Court. Prior to this it was called ‘Show Court One’. Please take a look at the seating plan before booking your seats for the Australian Open. A 700 million dollar project was undertaken in 2010- the Melbourne Park masterplan- and the renovation of the MCA was carried out under this project. The court was then transformed into a multi purpose venue for sporting and entertainment events alike. Seating capacity too increased from 6000 to 7500. Entertainment at Margaret Court Arena : Margaret Court Arena with its intimate seat setting and variable seating capacity that can range from 5000 to 8000, has become hot favorite among musicians and music enthusiasts alike, as a venue for live music. Australian hip hop pioneers Hilltop Hoods, performed at the MCA as a part of their Cosby Sweater Tour. Sports at Margaret Court Arena: Tennis: Margaret Court Arena is known to offer one of the best tennis viewing experiences to spectators. When the Margaret Court Arena opens its grounds to Australian Open this year, the Melbourne Park will become the only Grand Slam Tennis venue to have three stadiums with retractable roofs. -

Analysis of Barriers to Greater Use of the Melbourne BSS ENGN2226

U5349410 Analysis of barriers to greater use of the Melbourne BSS ENGN2226 Tutor : Ashley Ellis, Tutorial : Wednesday 15:00 - 17:00 10/14/2015 Abstract The following paper analyses Barriers to greater use of the Melbourne Bicycle Share system and offers recommendations to decrease their effect. The analysis was conducted from both a user's and owner's perspective and the recommendations take both their goals for the system into account. Human factors was the key analysis technique used as the barriers for the system came from a survey conducted on MBS users and non-users in Melbourne and Brisbane. Several recommendations were made based on information from this survey, the main one being an increase in the density of the stations. Energy Factors were not analyzed in this paper as they wouldn't offer any useful recommendations with regards to the barriers given the current system design. u5349410 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Recommendations ............................................................................................................................ 4 3. Qualitative ........................................................................................................................................ 4 3.1 Survey Design ............................................................................................................................ 4 4. Quantitative ..................................................................................................................................... -

How JOHN LEECH Raised the Ceiling on Sports Stadium Design

VOL. 3 NO. 2 MARCH 2017 GAME ON How JOHN LEECH raised the ceiling on sports stadium design Printing seeds War and water Out on a limb How 3D printers The engineer Inside efforts to can inspire the rebuilding vital make wood the next generation infrastructure in high-rise material of engineers war-torn Syria of the future COVER STORY 38 ENGINEERSAUSTRALIA.ORG.AU How did a materials handling engineer get asked to design stadium roofs and ferry wharves? By keeping Photo: Nathan Duff Photo: his eye on the ball and recognising opportunities for innovation. By Christopher Connolly. ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA | MARCH 2017 39 COVER STORY hen Aurecon recently won the job of redesigning the retractable roof on the Rod Laver Arena in Melbourne, it could W point to a lot of experience in this field both in Australia and overseas. But back in the 1990s when Connell Wagner (one of Aurecon’s forerunners) pitched for the job on the roof at Docklands Stadium in Melbourne, the team there had no experience. Luckily, it had a mechanical engineer in Queensland who had done a lot of work on large stockyard machines weighing 1000 t, which arguably have greater design challenges than those facing the roof at Docklands. “We put the case that it was actually less complex than these big, moving, materials handling machines that we had done a lot of,” says that engineer, John Leech. When Connell Wagner won that contract, Leech had to become an expert in retractable roofs quickly, exploring state-of-the-art solutions overseas. But he says the solution proposed was different to anything else being done at that time. -

Australian Open Packages 14-27 January 2019 | Melbourne Australia

2019 AUSTRALIAN OPEN PACKAGES 14-27 JANUARY 2019 | MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRALIAN OPEN 2019 ASTSPORTS.COM.AU | 1800 026 668 AUSTRALIAN SPORTS TOURS When you purchase your package through Australian Sports Tours, you can rest easy knowing that your tickets are 100% guaranteed by Tennis Australia. Our packages all come with reserved seating on Rod Laver Arena with the choice of Category 1, Category 2 & Category 3 seating. We off er a full range of accommodation to suit all budgets including 3 star, 4 star and 5 star hotels. Each of our hotels are ideally located in Melbourne’s CBD and are just a short walk or complimentary tram ride away from all the excitement and action at the fabulous Melbourne Park tennis and entertainment precinct. We look forward to providing you with the ultimate Grand Slam® tennis experience in 2019! The Team at Australian Sports Tours ASTSPORTS.COM.AU | 1800 026 668 AUSTRALIAN OPEN 2018 2 Australian Open 2017 Door number N Corporate seating Shade Restricted viewing seats ROD LAVER ARENA TICKETS PP323 PP343 PP359 PP379 PP301 PP401 65 30 31 The tickets included in our packages are Category PP280 64 32 63 33 PP422 3 Upper Level seating. You will also have the AA326 AA343 AA359 AA381 option to upgrade to Lower Level Category 2 or PP260 AA301 62 10 11 AA401 Lower Level Category 1 seating along with several U212 U227 34 AA280 9 U195 U243 12 PP442 AA422 hospitality options. U178 AA260 U260 PP239 61 35 U163 24 1122 AA442 Our reserved seating in Rod Laver Arena is sourced 8 23 3 PP463 AA239 13 through Helloworld/Qantas Holidays who have U275 60 4 AA463 been appointed as an Off icial Travel Agent to the 22 A195 A212 A227 A243 36 PP217 U146 A178 Australian Open 2019. -

The Arup Journal

ISSUE 2 2010 The Arup Journal B$UXSLQGG Contents 3 AAMI Park, Melbourne 25 The Denmark Pavilion, John Bahoric Greg Borkowski Expo 2010 Shanghai Peter Bowtell Tristram Carfrae Daniel Bosia Mikkel Kragh Frank Gargano Jarrod Hill Michael Kwok Nicolas Sterling Paul Stanley 34 Ropemaker Place, London EC2 16 North Melbourne station Michael Beaven Mick Brundle refurbishment Paul Dickenson Robert Pugh Joseph Correnza Patricia Culhane Marco Furlan Jochen Ristig Paul Stanley 1. AAMI Park on Melbourne’s famous Yarra River. 2 The Arup Journal 2/2010 B$UXSLQGG “The stadium is the latest jewel in the crown of AAMI Park, Melbourne’s sporting infrastructure, and will be the new home of soccer, rugby league and rugby union in Victoria. Victorians love their sport and AAMI Park Melbourne is the latest addition to a first-class suite of sporting infrastructure that is the envy of any city in the world.” James Merlino, Victoria Minister for Sport, Recreation and Youth Affairs John Bahoric Greg Borkowski Peter Bowtell Tristram Carfrae Frank Gargano Jarrod Hill Paul Stanley Overview and inception Awards 2008 Be Inspired Award of Excellence in the Innovation There is no other place in Australia that lives and breathes sport like Melbourne. in Commercial or Residential Building category As the traditional heartland of Australian Rules football, the city’s sporting venues are (Bentley Structural Awards) typically oval-shaped to accommodate AFL in the winter and cricket in summer. 2010 Structural Engineering Steel Building Design Award and Large Project - Architectural Steel Design Melbourne, however, also boasts a passion for codes that play on a rectangular (Australian Steel Institute Awards) pitch, and AAMI Park fills a major gap in the city’s sporting infrastructure, providing 2010 shortlisted for Award for Sports or Leisure soccer, rugby league and rugby union teams with Melbourne’s first purpose-built, Structures (Institution of Structural Engineers) rectangular-pitch stadium.