Creel 3 Digital Download (Pdf 1.3Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hill Walking & Mountaineering

Hill Walking & Mountaineering in Snowdonia Introduction The craggy heights of Snowdonia are justly regarded as the finest mountain range south of the Scottish Highlands. There is a different appeal to Snowdonia than, within the picturesque hills of, say, Cumbria, where cosy woodland seems to nestle in every valley and each hillside seems neatly manicured. Snowdonia’s hillsides are often rock strewn with deep rugged cwms biting into the flank of virtually every mountainside, sometimes converging from two directions to form soaring ridges which lead to lofty peaks. The proximity of the sea ensures that a fine day affords wonderful views, equally divided between the ever- changing seas and the serried ranks of mountains fading away into the distance. Eryri is the correct Welsh version of the area the English call Snowdonia; Yr Wyddfa is similarly the correct name for the summit of Snowdon, although Snowdon is often used to demarcate the whole massif around the summit. The mountains of Snowdonia stretch nearly fifty miles from the northern heights of the Carneddau, looming darkly over Conwy Bay, to the southern fringes of the Cadair Idris massif, overlooking the tranquil estuary of the Afon Dyfi and Cardigan Bay. From the western end of the Nantlle Ridge to the eastern borders of the Aran range is around twenty- five miles. Within this area lie nine distinct mountain groups containing a wealth of mountain walking possibilities, while just outside the National Park, the Rivals sit astride the Lleyn Peninsula and the Berwyns roll upwards to the east of Bala. The traditional bases of Llanberis, Bethesda, Capel Curig, Betws y Coed and Beddgelert serve the northern hills and in the south Barmouth, Dinas Mawddwy, Dolgellau, Tywyn, Machynlleth and Bala provide good locations for accessing the mountains. -

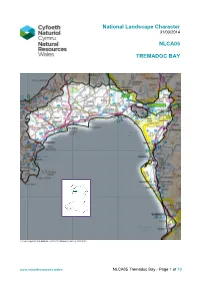

NLCA05 Tremadoc Bay - Page 1 of 10

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA05 TREMADOC BAY © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 www.naturalresources .wales NLCA05 Tremadoc Bay - Page 1 of 10 Bae Tremadog – Disgrifiad cryno Dyma gesail ogleddol Bae Ceredigion, tir llawr gwlad hynod ddiddorol a phrydferth. Dyma’r tir rhwng y môr a’r mynydd. I’r dwyrain o Borthmadog mae sawl aber tywodlyd gyda halwyndiroedd, ac i’r de mae milltiroedd o draethau agos-barhaus, ac weithiau anghysbell, â thwyni tywod y tu cefn iddynt. Mae’r tiroedd eang tua’r gorllewin o gymeriad mwy amaethyddol. Mae’r fro’n gwrthgyferbynnu’n drawiadol â’i chefndir mynyddig, Ll ŷn ac Eryri. Mae'r ddau Moelwyn, Y Cnicht, Y Rhinogydd, Yr Eifl a hyd yn oed yr Wyddfa oll yn amlwg iawn i’w gweld. Yn ymyl Porthmadog, mae mynydd ynysig llai, ond garw, Moel-y-gest yn codi’n ddisymwth o dir yr ardal hon. I’r de o Borthmadog mae'r môr a’r mynyddoedd yn cyfyngu ar led llawr gwlad, a dau’r ddau at ei gilydd ychydig i’r de o Friog. Mae llawer o bentrefi yma, ac yn gyffredinol, cymeriad gwledig, amaethyddol sydd i’r fro, ac eithrio yn nhrefi Abermo, Porthmadog a Phwllheli a’u cyffiniau. Ceir eglwysi glan môr hynafol a chestyll mawrion ar hyd y glannau, i’n hatgoffa o ba mor bwysig oedd y môr ar gyfer teithio, a phwysigrwydd strategol yr ardal hon. Awgrymir hyn yn y cysylltiad a geir, yn y Mabinogi, rhwng Harlech ac Iwerddon: ac yn ddiweddarach, adfywiwyd trefi canoloesol Pwllheli, Cricieth, Harlech ac Abermo gan dwf twristiaeth yn y 19eg ganrif. -

Parys Mountain, Anglesey

YRC JOURNAL Exploration, mountaineering and caving since 1892 issue 21 Series 13 SUMMER 2016 Articles Trekking in Morroco Azerbaijan Summer Isles Parys Mountain MOUNTAINS OF MOURNE ROSEBERRY TOPPING PHOTOGRAPH CHRIS SWINDEN 1 CONTENTS 3 Editorial 4 Azerbaijan John & Valerie Middleton 8 Invasion Roy Denney 10 Summer Isles Alan Linford 11 Poet’s Corner Wm Cecil Slingsby 12 Australia Iain Gilmour 13 Parys Mountain Tim Josephy 16 Chippings 21 Natural History 26 Obituaries and appreciations 33 Morocco 48 Reviews 49 UK Meet reports Jan 8-10 Little Langdale, Cumbria Jan 28-31 Glencoe, Scotland Feb 26-28 Cwm Dyli, Wales Mar 18-20 Newtonmoor, Scotland Apr 22-24 Thirlmere, Cumbria May 7-14 Leverburgh, Harris May 20-22 North Wales Jun 10-12 Ennerdale, Cumbria YRC journal Page 2 EDITORS NOTE The Club has been in existence almost We have been trawling through the 124 years which means next year will archives and old journals checking facts be something of a celebration and we and looking for material to include and it look forward to an interesting meets has reminded us that we have lots of spare programme. copies of old journals. We always print a few spares to replace members lost ones We are also bringing out a special edition and to be able to provide recent ones to of the Journal to mark the occasion. Work prospective members but invariably there on it is well advanced and I would like to are a few left over. thank the many members who have provided me with snippets and old In addition, many members’ families give photographs. -

Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr

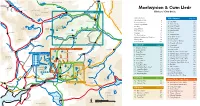

Llanrwst Llyn Padarn Llyn Ogwen CARNEDDAU Llanberis A5 Llyn Peris B5427 Tryfan Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr A4086 Nant Peris GLYDERAU B5106 Glyder Fach Capel Curig CWM LLEDR MAP PAGE 123 Climbers’ Club Guide Glyder Fawr LLANBERIS PASS A4086 Llynnau Llugwy Mymbyr Introduction A470 Y Moelwynion page 123 The Climbers’ Club 4 Betws-y-Coed Acknowledgments 5 20 Stile Wall 123 B5113 21 Craig Fychan 123 13 Using this guidebook 6 6 Grading 7 22 Craig Wrysgan 123 Carnedd 12 Carnedd Moel-siabod 5 9 10 23 Upper Wrysgan 123 SNOWDON Crag Selector 8 Llyn Llydaw y Cribau 11 3 4 Flora & Fauna 10 24 Moel yr Hydd 123 A470 A5 Rhyd-Ddu Geology 14 25 Pinacl 123 Dolwyddelan Lledr Conwy The Slate Industry 18 26 Waterfall Slab 123 Llyn Gwynant 2 History of Moelwynion Climbing 20 27 Clogwyn yr Oen 123 1 Pentre 8 B4406 28 Carreg Keith 123 Yr Aran -bont Koselig Hour 28 Plas Gwynant Index of Climbs 000 29 Sleep Dancer Buttress 123 7 Penmachno A498 30 Clogwyn y Bustach 123 Cwm Lledr page 30 31 Craig Fach 123 A4085 Bwlch y Gorddinan (Crimea Pass) 1 Clogwyn yr Adar 32 32 Craig Newydd 123 Llyn Dinas MANOD & The TOWN QUARRIES MAP PAGE 123 Machno Ysbyty Ifan 2 Craig y Tonnau 36 33 Craig Stwlan 123 Beddgelert 44 34 Moelwyn Bach Summit Cliffs 123 Moel Penamnen 3 Craig Ddu 38 Y MOELWYNION MAP PAGE 123 35 Moelwyn Bach Summit Quarry 123 Carrog 4 Craig Ystumiau 44 24 29 Cnicht 47 36 Moelwyn Bach Summit Nose 123 Moel Hebog 5 Lone Buttress 48 43 46 B4407 25 30 41 Pen y Bedw Conwy 37 Moelwyn Bach Craig Ysgafn 123 42 Blaenau Ffestiniog 6 Daear Ddu 49 26 31 40 38 38 Craig Llyn Cwm Orthin -

Coach Leaves Heswall 8

WIRRAL RAMBLERS SUNDAY 3rd APRIL 2016 Moelwyns (Tan y grisiau 6.00pm) (Coach mobile number: 07895 152449) Liscard 8.30am Heswall 9.00am A Walk Rucksacks on the coach please Today's walk starts at G. R. 696475. We will climb Moel Penamnen and Moel Farwyd before crossing the A470 and climbing Allt Fawr, Moel y Hyde, Moelwyn Mawr, and Moelwyn Bach. Some rough going and a short exposed path. Distance: 17.6 kms (11 miles) Points: 19.5 Ascent: 1387m (4200ft) B Plus Walk From Tanygrisiau walk alongside waterfalls and Llyn Cwmorthin up to atmospheric abandoned quarries, mines and a deserted village. We climb first Moel-yr-hydd, then Moelwyn Mawr, cross Craigysgain and ascend Meolwyn Bach. Dropping down to Llyn Stwlan dam we head SE to Tanygrisiau reservoir and follow the Ffestiniog Railway back to the village. An interesting, scenic walk that has not been reccied. Distance: 13.5 kms (8.5 miles) Points: 16 Ascent: 1050m (3500ft) B Minus Walk A modestly paced mountain walk for summit B- walkers who can tackle steep ascents and descents with short section of exposure. Leaving Tanygrisiau Reservoir by track N&W, past Llyn Cwmorthin, we reach the col/ quarry ruins for lunch. Climb (75 mins) SW by grass ridge to Moelwyn Mawr & descend SE on grass, rough terrain on Craigysgafn (589m) to Bwlch Stwlan col. A return ascent (40 mins) by rough path to Moelwyn Bach (710m) follows. Leaving the col NE on grass to the Stwlan Dam,descend to the cafe. Two points extra for steepness/exposure. Distance: 10kms (6 miles) Points: 13 Ascent: 700m (2300ft) C Walk From Tanygrisiau, 685 448 pass N end of reservoir and follow path on W side. -

MOUNTAIN RESCUE TEAM LOG BOOK from 22Nd OCTOBER 58

MOUNTAIN RESCUE TEAM LOG BOOK FROM 22nd OCTOBER 58 TO 27th MARCH 60 1 NOTES 1 This Diary was transcribed by Dr. A. S. G. Jones between February and July, 2014 2 He has attempted to follow, as closely as possible, the lay-out of the actual entries in the Diary. 3 The first entry in this diary is dated 22nd October 1958. The last entry is dated 27th March, 1960 4 There is considerable variation in spellings. He has attempted to follow the actual spelling in the Diary even where the Spell Checker has highlighted a word as incorrect. 5 The spelling of place names is a very variable feast as is the use of initial capital letters. He has attempted to follow the actual spellings in the Diary 6 Where there is uncertainty as to a word, its has been shown in italics 7 Where words or parts of words have been crossed out (corrected) they are shown with a strike through. 8 The diary is in a S.O.Book 445. 9 It was apparent that the entries were written by number of different people 10 Sincere thanks to Alister Haveron for a detailed proof reading of the text. Any mistakes are the fault of Dr. A. S. G. Jones. 2 INDEX of CALL OUTS to CRASHED AIRCRAFT Date Time Group & Place Height Map Ref Aircraft Time missing Remarks Pages Month Type finding November 58 101500Z N of Snowdon ? ? ? False alarm 8 May 1959 191230Z Tal y Fan 1900' 721722 Anson 18 hrs 76 INDEX of CALL OUTS to CIVILIAN CLIMBING ACCIDENTS Date Time Group & Place Map Time Names Remarks Pages Month reference spent 1958 November 020745Z Clogwyn du'r Arddu 7 hrs Bryan MAYES benighted 4 Jill SUTTON -

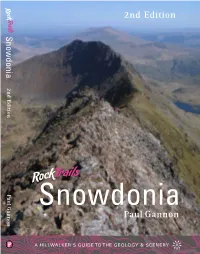

Paul Gannon 2Nd Edition

2nd Edition In the first half of the book Paul discusses the mountain formation Paul Gannon is a science and of central Snowdonia. The second half of the book details technology writer. He is author Snowdonia seventeen walks, some easy, some more challenging, which bear Snowdonia of the Rock Trails series and other books including the widely evidence of the story told so far. A HILLWalker’s guide TO THE GEOLOGY & SCENERY praised account of the birth of the Walk #1 Snowdon The origins of the magnificent scenery of Snowdonia explained, and a guide to some electronic computer during the Walk #2 Glyder Fawr & Twll Du great walks which reveal the grand story of the creation of such a landscape. Second World War, Colossus: Bletchley Park’s Greatest Secret. Walk #3 Glyder Fach Continental plates collide; volcanoes burst through the earth’s crust; great flows of ash He also organises walks for hillwalkers interested in finding out Walk #4 Tryfan and molten rock pour into the sea; rock is strained to the point of catastrophic collapse; 2nd Edition more about the geology and scenery of upland areas. Walk #5 Y Carneddau and ancient glaciers scour the land. Left behind are clues to these awesome events, the (www.landscape-walks.co.uk) Walk #6 Elidir Fawr small details will not escape you, all around are signs, underfoot and up close. Press comments about this series: Rock Trails Snowdonia Walk #7 Carnedd y Cribau 1 Paul leads you on a series of seventeen walks on and around Snowdon, including the Snowdon LLYN CWMFFYNNON “… you’ll be surprised at how much you’ve missed over the years.” Start / Finish Walk #8 Northern Glyderau Cwms A FON NANT PERIS A4086 Carneddau, the Glyders and Tryfan, Nant Gwynant, Llanberis Pass and Cadair Idris. -

Cirque Glaciers in Snowdonia, North Wales

Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 123 (2012) 130–145 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pgeola Palaeoclimatic reconstruction from Lateglacial (Younger Dryas Chronozone) cirque glaciers in Snowdonia, North Wales Jacob M. Bendle, Neil F. Glasser * Centre for Glaciology, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion SY23 3DB, UK A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: The cirques of Snowdonia, North Wales were last occupied by glacier ice during the Younger Dryas Received 13 July 2011 Chronozone (YDC), c. 12.9–11.7 ka. New mapping presented here indicates 38 small YDC cirque glaciers Received in revised form 9 September 2011 2 formed in Snowdonia, covering a total area of 20.74 km . Equilibrium line altitudes (ELAs) for these Accepted 13 September 2011 glaciers, calculated using an area–altitude balance ratio (AABR) approach, ranged from 380 to 837 m asl. Available online 9 November 2011 A northeastwards rise in YDC ELAs across Snowdonia is consistent with southwesterly snow-bearing winds. Regional palaeoclimate reconstructions indicate that the YDC in North Wales was colder and drier Keywords: than at present. Palaeotemperature and annual temperature range estimates, derived from published Cirque glaciers palaeoecological datasets, were used to reconstruct values of annual accumulation and ‘winter balance Palaeoclimatic reconstructions plus summer precipitation’ using a degree-day model (DDM) and non-linear regression function, Degree-day model Younger Dryas respectively. The DDM acted as the best-estimate for stadial precipitation and yielded values between À1 À1 À1 À1 Snowdonia 2073 and 2687 mm a (lapse rate: 0.006 8C m ) and 1782–2470 mm a (lapse rate: 0.007 8C m ). -

Ucheldir Y Gogledd Part 1: Description

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREA 1: UCHELDIR Y GOGLEDD PART 1: DESCRIPTION SUMMARY OF LOCATION AND BOUNDARIES Ucheldir y Gogledd forms the first significant upland landscape in the northern part of the National Park. It includes a series of peaks - Moel Wnion, Drosgl, Foel Ganol, Pen y Castell, Drum, Carnedd Gwenllian, Tal y Fan and Conwy Mountain rising between 600 and 940m AOD. The area extends from Bethesda (which is located outside the National Park boundary) in the west to the western flanks of the Conwy valley in the east. It also encompasses the outskirts of Conwy to the north to form an immediate backdrop to the coast. 20 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREA 1: UCHELDIR Y GOGLEDD KEY CHARACTERISTICS OF THE LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREA1 Dramatic and varied topography; rising up steeply from the Conwy coast Sychnant Pass SSSI, in the north-east of the LCA, comprising dry heath, acid at Penmaen-bach Point to form a series of mountains, peaking at Foel-Fras grassland, bracken, marshland, ponds and streams – providing a naturalistic backdrop (942 metres). Foothills drop down from the mountains to form a more to the nearby Conwy Estuary. intricate landscape to the east and west. Wealth of nationally important archaeological features including Bronze Age Complex, internationally renowned geological and geomorphological funerary and ritual monuments (e.g. standing stones at Bwlch y Ddeufaen), prominent landscape, with a mixture of igneous and sedimentary rocks shaped by Iron Age hillforts (e.g. Maes y Gaer and Dinas) and evidence of early settlement, field ancient earth movements and exposed and re-modelled by glaciation. systems and transport routes (e.g. -

Confronting Loss and Flux in the Slate Industry Ruins of Northwest Wales

Mining Things: Confronting Loss and Flux in the Slate Industry Ruins of Northwest Wales Seb Wigdel-Bowcott Figure 1 Rhosydd Quarry level 9, with the ruins of the barracks to the left and the outline of the mill to its right. Image courtesy of the author, August 2019. Returning to a familiar environment after a prolonged absence has a strange way of pulling features out from their habitualness. This was my experience during a visit to the ruins on level 9 of Rhosydd Quarry, which formed part of a walk with friends on the mountain, Cnicht, and surrounding Cwm Croesor, while on a visit back to the area of northwest Wales where I grew up. The physical traces of the slate industry that had occupied a seamless place among my everyday surroundings now seemed to demand a recognition of a certain out-of-placeness. What I previously understood as the idiosyncrasies of a Refract | Volume 3 Issue 1 144 landscape shaped by a formerly world-leading national industry, I now saw as geological scars that stand as monuments to an industrial capitalism that exited as aggressively as it imposed itself, testifying to its remarkable ability to reshape environments both physical and social. There is a powerful sense of a threshold being crossed when reaching the site of the level 9 ruins from Cnicht. The plateau-like micro-landscape formed by the slate waste makes for a stark physical border when stepping off the mountain’s exterior and onto its excavated rock. One side of the clearing opens out onto the valley, with the other side enclosed partly by the mountain and the towering waste tips from the quarry’s upper levels. -

Mountains of Wales a L Ist

THIS LIST MAY BE FREELY DISTRIBUTEDAND REPRODUCED PROVIDING THAT THE INFORMATION IS NOT MODIFIED , AND THAT ORIGINAL AUTHORS ARE GIVEN CREDIT . N O INDIVIDUAL OR ORGANIZATION MAY MAKE FINANCIAL GAIN IN DOING SO WITHOUT EXPRESS PERMISSION OF MUD AND ROUTES MOUNTAINS OF WALES A L IST WELSH AND SIX HUNDRED IN STATURE (WASHIS) PB7 2 What are the WASHIS? Well, Scotland has it’s Munros (among others) and the Lakes have their Wain- rights. Wales doesn’t have a list of summits in it’s own right. While there are hills known as Nualls, they are not specific to Wales and include an ever in- creasing list of summits with 30 metres drop all around, making for a long list. It is also rather patronising for the Welsh and English hills (which I do not con- cern myself with here) to be included with that of a neighbouring country. Some lists also sck to the old imperial figure of 2000 feet making a mountain, or 610 metres, which really is rather clumsy in metric. Washis are all the hills in Wales that are over 600m and have at least 50 me- tres drop all around. Some notable tops have not made it into the main list, including some of the tradional ‘3000 Footers’. There are some other sum- mits missing from the list. Y Garn on the Nantlle ridge for one, an excellent viewpoint or Bera Mawr, an excellent lile scramble to the summit tor. Fan Y Big in the Beacons fails to make it too. Just because they’re not on the list, doesn’t mean they’re not worth vising. -

Summits on the Air Wales Association Reference Manual

Summits on the Air Wales Association Reference Manual Document Reference S2.1 Issue number 2.3 Date of issue 02 March 2018 Participation start date 02 March 2002 Authorised: John Linford, G3WGV Date: 01 April 2002 Association Manager Roger Dallimore, MW0IDX Management Team G3WGV, GM4ZFZ, MM0FMF, G0CQK, G3WGV, M1EYP, G8ADD, GM4TOE, G0HRT, G4TJC, K6EL. Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. The source data used in the Marilyn lists herein is copyright of Alan Dawson and is used with his permission. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Table of Contents 1 CHANGE CONTROL ................................................................................................................................. 1 2 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ...................................................................................................... 2 2.1 PROGRAMME DERIVATION ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................................................................................ 2 2.3 RIGHTS OF WAY AND ACCESS ISSUES .................................................................................................... 3 2.4 MAPS AND NAVIGATION ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.5 SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS