The Team That Invented College Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1951 Grizzly Football Yearbook University of Montana—Missoula

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Grizzly Football Yearbook, 1939-2014 Intercollegiate Athletics 9-1-1951 1951 Grizzly Football Yearbook University of Montana—Missoula. Athletics Department Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlyfootball_yearbooks Recommended Citation University of Montana—Missoula. Athletics Department, "1951 Grizzly Football Yearbook" (1951). Grizzly Football Yearbook, 1939-2014. 5. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/grizzlyfootball_yearbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Intercollegiate Athletics at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grizzly Football Yearbook, 1939-2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS Press and Radio Information.......................... 1 Mountain States Conference Schedule . c ............... 2 1951 Schedule, 1950 Results, All-Time Record............ 3 General Information on Montana University............. U The 1951 Grizzly Coaching Staff....................... 5 1951 Outlook....................................... 8 1951 Football Roster................................ 10 Thumbnail Sketches of Flayers....................... 12 Pronunciation...................................... 18 Squad Summary By Positions........................... 19 Experience Breakdown................................ 20 Miscellaneous................................... -

OSU Baseball 2019 Media Gu

TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS THE UNIVERSITY TEAM INFORMATION Location ............................................ Stillwater, Okla. 2018 Record ..................................................... 31-26-1 Founded ........................................... 1890 2018 Big 12 Conf. Record ............................... 16-8 Enrollment ....................................... 35,073 2018 Conference Finish .................................. 2nd Nickname ......................................... Cowboys 2018 Postseason ........... NCAA DeLand Regional finals Colors ............................................... Orange & Black 2018 Final Ranking .......................................... n/a Conference ...................................... Big 12 Letterwinners Returning/Lost ........................ 18/14 Affiliation ......................................... NCAA Division I Starters Returning/Lost .................................. 4/5 President .......................................... Burns Hargis Pitchers Returning/Lost .................................. 10/5 VP for Athletic Programs ................ Mike Holder Ath. Dept. Phone ............................. (405) 744-7050 Key Returners (2018 stats) Ticket Office Phone ......................... (405) 744-5745 or (Position players) 877-255-4678 (ALL4OSU) Trevor Boone, OF - .270, 10 HR, 33 RBI Cade Cabbiness, OF - .132, 3 HR, 7 RBI OSU BASEBALL HISTORY Christian Funk, INF - .245, 7 HR, 33 RBI GENERAL INFORMATION First Year of Baseball ......................1909 Carson McCusker, OF - .271, -

Front Matter

Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi INTRODUCTION The Cultural Cornerstone of the Ivory Tower 1 CHAPTER ONE Physical Culture, Discipline, and Higher Education in 1800s America 14 CHAPTER TWO Progressive Era Universities and Football Reform 40 CHAPTER THREE Psychologists: Body, Mind, and the Creation of Discipline 71 CHAPTER FOUR Social Scientists: Making Sport Safe for a Rational Public 93 CHAPTER FIVE Coaches: In the Disciplinary Arena 115 CHAPTER SIX Stadiums: Between Campus and Culture 139 CHAPTER SEVEN Academic Backlash in the Post–World War I Era 171 EPILOGUE A Circus or a Sideshow? 200 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. viii Contents Notes 207 Bibliography 269 Index 305 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Illustrations 1. Opening ceremony, Leland Stanford Junior University, October 1891 2 2. Walter Camp, captain of the Yale football team, circa 1880 35 3. Grant Field at Georgia Tech, 1920 41 4. Stagg Field at the University of Chicago 43 5. William Rainey Harper built the University of Chicago’s academic reputation and also initiated big-time athletics at the institution 55 6. Army-Navy game at the Polo Grounds in New York, 1916 68 7. G. T. W. Patrick in 1878, before earning his doctorate in philosophy under G. -

Glenn Killinger, Service Football, and the Birth

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Humanities WAR SEASONS: GLENN KILLINGER, SERVICE FOOTBALL, AND THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN HERO IN POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation in American Studies by Todd M. Mealy © 2018 Todd M. Mealy Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 ii This dissertation of Todd M. Mealy was reviewed and approved by the following: Charles P. Kupfer Associate Professor of American Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Simon Bronner Distinguished Professor Emeritus of American Studies and Folklore Raffy Luquis Associate Professor of Health Education, Behavioral Science and Educaiton Program Peter Kareithi Special Member, Associate Professor of Communications, The Pennsylvania State University John Haddad Professor of American Studies and Chair, American Studies Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Glenn Killinger’s career as a three-sport star at Penn State. The thrills and fascinations of his athletic exploits were chronicled by the mass media beginning in 1917 through the 1920s in a way that addressed the central themes of the mythic Great American Novel. Killinger’s personal and public life matched the cultural medley that defined the nation in the first quarter of the twentieth-century. His life plays outs as if it were a Horatio Alger novel, as the anxieties over turn-of-the- century immigration and urbanization, the uncertainty of commercializing formerly amateur sports, social unrest that challenged the status quo, and the resiliency of the individual confronting challenges of World War I, sport, and social alienation. -

Ben Lee Boynton:The Purple Streak

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 25, No. 3 (2003) Ben Lee Boynton:The Purple Streak by Jeffrey Miller The 1924 season was one of transition for Buffalo’s pro football team. The All-Americans, as the team had been known since its founding in 1920, had been very successful in its four year history, finishing within one game of the league championship in both the 1920 and 1921 seasons. But successive 5-4 campaigns and declining attendance had convinced owner Frank McNeil that it was time to get out of the football business. McNeil sold the franchise to a group led by local businessman Warren D. Patterson and Tommy Hughitt, the team’s player/coach, for $50,000. The new ownership changed the name of the team to Bisons, and committed themselves signing big name players in an effort to improve performance both on the field and at the box office. The biggest transaction of the off-season was the signing of “the Purple Streak,” former Williams College star quarterback Benny Lee Boynton. Boynton, a multiple All America selection at Williams, began his pro career with the Rochester Jeffersons in 1921. His signing with the Bisons in 1924 gave the Buffalo team its first legitimate star since Elmer Oliphant donned an orange and black sweater three years earlier. Born Benjamin Lee Boynton on December 6, 1898 in Waco, Texas, to Charles and Laura Boynton, Ben Lee learned his love of football at an early age. He entered Waco High School in 1912, and the next year began a string of three consecutive seasons and Waco’s starting quarterback. -

Football Award Winners

FOOTBALL AWARD WINNERS Consensus All-America Selections 2 Consensus All-Americans by School 20 National Award Winners 32 First Team All-Americans Below FBS 42 NCAA Postgraduate scholarship winners 72 Academic All-America Hall of Fame 81 Academic All-Americans by School 82 CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICA SELECTIONS In 1950, the National Collegiate Athletic Bureau (the NCAA’s service bureau) compiled the first official comprehensive roster of all-time All-Americans. The compilation of the All-America roster was supervised by a panel of analysts working in large part with the historical records contained in the files of the Dr. Baker Football Information Service. The roster consists of only those players who were first-team selections on one or more of the All-America teams that were selected for the national audience and received nationwide circulation. Not included are the thousands of players who received mention on All-America second or third teams, nor the numerous others who were selected by newspapers or agencies with circulations that were not primarily national and with viewpoints, therefore, that were not normally nationwide in scope. The following chart indicates, by year (in left column), which national media and organizations selected All-America teams. The headings at the top of each column refer to the selector (see legend after chart). ALL-AMERICA SELECTORS AA AP C CNN COL CP FBW FC FN FW INS L LIB M N NA NEA SN UP UPI W WCF 1889 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – √ – 1890 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – √ – 1891 – – – -

Statistical Supplement

STATISTICAL SUPPLEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS INDIVIDUAL SINGLE-GAME RECORDS TABLE OF CONTENTS Individual Single-Game Records Team Records Passing Single-Game 45 Records 4 Single-Season 46 300-Yard Passing Games 5 Rushing Cougars in the Draft Records 6 WSU Draft History 48-50 100-Yard Rushing Games 7 150-Yard Rushing Games 8 Cougars in the Pros Receiving WSU All-Time Professional Roster 52-53 Records 9 NFL All-Pros 54 100-Yard Receiving Games 10 NFL Award Winners 55 150-Yard Receiving Games 11 Active Professionals 56 Total Offense/All-Purpose Records 12 Defense Single-Game Superlatives Records 13-14 Record By Month and Day / Special Teams Scoring Margins 58 Return Records 15 Homecoming Record 59 Kicking Records 16 Dad’s Day Record 60 Punting Records 17 WSU Coaches Individual Single-Season Records Head Coaches 62-64 Passing Assistant Coaches 65-66 Records 19 All-Time Coaches 67 3,000-Yard Passers 20 Yearly Leaders 21 Results Rushing Vs. opponent 69-70 Records 22 Year-by-Year 71-75 1,000-Yard Rushers 23-24 Vs. Conference 76 Yearly Leaders 25 Receiving Cougar Award Winners Records 26 National Awards 78-80 1,000-Yard Receivers 27 Conference Awards 81-82 Yearly Leaders 28 Team Awards 83 Total offense/All-Purpose Academic Awards 84 Records 29 yearly Leaders 30 Bowl Games Defense Game Recaps 86-90 Tackle Records 31 Individual Records 91-92 Tackle Yearly Leaders 32 Team Records 93-94 Interception Records / Yearly Leaders 33 Special Teams Punt Return Records / Yearly Leaders 34 Kickoff Return Records / Yearly Leaders 35 Kicking Records 36 Scoring Yearly Leaders 37 Punting Records / Yearly Leaders 38 Individual Career Records Offense 40-41 Defense 42 Special Teams 43 2 WASHINGTON STATE FOOTBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS INDIVIDUAL SINGLE-GAME RECORDS PASSING PASS ATTEMPTS TOUCHDOWNS Rk. -

The Wild Bunch a Side Order of Football

THE WILD BUNCH A SIDE ORDER OF FOOTBALL AN OFFENSIVE MANUAL AND INSTALLATION GUIDE BY TED SEAY THIRD EDITION January 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION p. 3 1. WHY RUN THE WILD BUNCH? 4 2. THE TAO OF DECEPTION 10 3. CHOOSING PERSONNEL 12 4. SETTING UP THE SYSTEM 14 5. FORGING THE LINE 20 6. BACKS AND RECEIVERS 33 7. QUARTERBACK BASICS 35 8. THE PLAYS 47 THE RUNS 48 THE PASSES 86 THE SPECIALS 124 9. INSTALLATION 132 10. SITUATIONAL WILD BUNCH 139 11. A PHILOSOPHY OF ATTACK 146 Dedication: THIS BOOK IS FOR PATSY, WHOSE PATIENCE DURING THE YEARS I WAS DEVELOPING THE WILD BUNCH WAS MATCHED ONLY BY HER GOOD HUMOR. Copyright © 2006 Edmond E. Seay III - 2 - INTRODUCTION The Wild Bunch celebrates its sixth birthday in 2006. This revised playbook reflects the lessons learned during that period by Wild Bunch coaches on three continents operating at every level from coaching 8-year-olds to semi-professionals. The biggest change so far in the offense has been the addition in 2004 of the Rocket Sweep series (pp. 62-72). A public high school in Chicago and a semi-pro team in New Jersey both reached their championship game using the new Rocket-fueled Wild Bunch. A youth team in Utah won its state championship running the offense practically verbatim from the playbook. A number of coaches have requested video resources on the Wild Bunch, and I am happy to say a DVD project is taking shape which will feature not only game footage but extensive whiteboard analysis of the offense, as well as information on its installation. -

Native America's Pastime

Native America’s Pastime How Football at an Indian Boarding School Empowered Native American Men and Revitalized their Culture, 1880-1920 David Gaetano Candidate for Senior Honors in History, Oberlin College Thesis advisor: Professor Matthew Bahar Spring 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Part I: Pratt and the Euro-American Perspective …………………. 15 Part II: Carlisle Football and the Indian Perspective ……………. 33 Conclusion .............................................................................. 58 Bibliography ............................................................................ 61 2 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I want to thank Professor Matthew Bahar for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout not only the duration of this project, but my time here at Oberlin College. I was taught by Professor Bahar on four separate occasions, beginning with the first class I ever took at Oberlin in “American History to 1877” and ending with “Indians and Empires in Early America” my junior spring. He also led a private reading on the American Revolution and served as my advisor since I declared for a history major as a freshman. Most importantly, Professor Bahar has been a thoughtful mentor and someone I will always consider a friend. I am fortunate to have had the privilege of learning from him, both as an academic and as a person of tremendous character. I am extremely grateful of his impact on my life and look forward to staying in contact over the years. I would also like to thank the many history and economics professors whose classes I have had the privilege of taking. Professor Leonard Smith has been an absolute joy to get to know both in and out of the classroom. -

Protest at the Pyramid: the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Protest at the Pyramid: The 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B. Witherspoon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PROTEST AT THE PYRAMID: THE 1968 MEXICO CITY OLYMPICS AND THE POLITICIZATION OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES By Kevin B. Witherspoon A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Kevin B. Witherspoon defended on Oct. 6, 2003. _________________________ James P. Jones Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member _________________________ Valerie J. Conner Committee Member _________________________ Robinson Herrera Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been completed without the help of many individuals. Thanks, first, to Jim Jones, who oversaw this project, and whose interest and enthusiasm kept me to task. Also to the other members of the dissertation committee, V.J. Conner, Robinson Herrera, Patrick O’Sullivan, and Joe Richardson, for their time and patience, constructive criticism and suggestions for revision. Thanks as well to Bill Baker, a mentor and friend at the University of Maine, whose example as a sports historian I can only hope to imitate. Thanks to those who offered interviews, without which this project would have been a miserable failure: Juan Martinez, Manuel Billa, Pedro Aguilar Cabrera, Carlos Hernandez Schafler, Florenzio and Magda Acosta, Anatoly Isaenko, Ray Hegstrom, and Dr. -

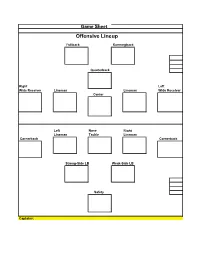

Offensive Lineup

Game Sheet Offensive Lineup Fullback Runningback Quarterback Right Left Wide Receiver Lineman Lineman Wide Receiver Center Left Nose Right Lineman Tackle Lineman Cornerback Cornerback Strong-Side LB Weak-Side LB Safety Captains: Game Sheet Kickoff Return Team Back Back Middleback Lineman Lineman Middleback Lineman Lineman Kickoff Team Kicker Steelers Game Sheet Punt Team Runningback Runningback Punter Right Left Wide Receiver Lineman Lineman Wide Receiver Center Punt Return Team Lineman Lineman Lineman Cornerback Cornerback Middle back Back Back Play Sheet # Formation Play Run or Pass 1 Standard formation Dive right Run 2 Slot right formation Trap Dive right Run 3 Standard formation Blast right Run 4 Slot right formation Option right Run 5 Slot right formation Option pass right Pass 6 Slot right formation Pitch right Run 7 Slot right formation Bootleg left Run 8 Slot right formation Bootleg Pass Pass 9 Split Backs Counter Dive Right Run 10 Slot right formation Fake pitch right, counter Run 11 Spread formation Reverse Right Run 12 Spread formation Fake Reverse Right Run 13 Slot right formation Motion Handoff Left Run 14 Slot left formation Motion Pass Right Pass 15 Slot left formation Wildcat Run Right Run 16 Slot left formation Wildcat Pass Right Pass 17 Slot left formation Wildcat Bomb Left Pass 18 Slot right formation Tunnel Run Left Run 19 Slot right formation Pitch right, halfback pass Pass 20 Slot right formation Pitch right, QB throwback Pass 21 Slot right formation Shovel Pass Left Pass 22 Slot right formation Trap Pass Pass 23 -

Intercollegiate Football Researchers Association ™

INTERCOLLEGIATE FOOTBALL RESEARCHERS ASSOCIATION ™ The College Football Historian ™ Presenting the sport’s historical accomplishments…written by the author’s unique perspective. ISSN: 2326-3628 [January 2016… Vol. 8, No. 12] circa: Feb. 2008 Tex Noël, Editor ([email protected]) Website: http://www.secsportsfan.com/college-football-association.html Disclaimer: IFRA is not associated with the NCAA, NAIA, NJCAA or their colleges and universities. All content is protected by copyright© by the original author. FACEBOOK: https://www.facebook.com/theifra Happy New Year...May it be your best year in all that you do; wish and you set-out to accomplish; and may your health be strong-vibrant and sustain you during your journey in this coming year!!! THANK YOU FOR ANOTHER OUTSTANDING YEAR! How Many Jersey Numbers of Heisman Trophy Winners Can You Name? By John Shearer About four years ago, I wrote a story about the jersey numbers that the Heisman Trophy winners have worn. I decided to write the article after noticing that 2011 Heisman Trophy winner Robert Griffin III of Baylor wore No. 10, and I began wondering which other Heisman Trophy winners wore that number. That started an online search, and I was able to find everyone’s number, or at least a number the player wore during part of his career. I wrote the story in chronological order by year and mentioned the jersey number with each player, but someone emailed me and said he would like to see a story if I ever listed the Heisman Trophy winners in numerical order. After I thought about it, an article written that way would make for a more The College Football Historian-2 - interesting story.