6 the Genesis of the Honour of Wallingford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

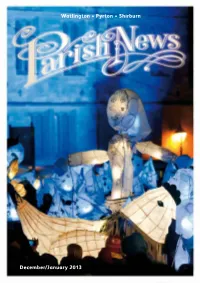

Watlington • Pyrton • Shirburn December/January 2013

Watlington • Pyrton • Shirburn December/January 2013 1 CHRISTMAS WREATH MAKING WORKSHOPS B C J 2 Contents Dates for St.Leonards p.26-27 your diary Pyrton p.13 Advent Service of readings and Methodists p.14-15 music 4pm Sunday 2nd December Church services p.6-7 Christmas childrens services p.28 News from Registers p.33 Christmas Carol Services p.29 Ministry Team p.5 4 All Services p.19 Watlington Christmas Fair 1st Dec p.18 Christmas Tree Festival 8th-23rd December p.56 From the Editor A note about our Cover Page - Our grateful thanks to Emily Cooling for allowing us to use a photo of one of her extraordinary and enchanting Lanterns featured in the Local schools and community groups’ magical Oxford Lantern Parade. We look forward to writing more about Emily, a professional Shirburn artist; her creative children’s workshops and much more – Her website is: www.kidsarts.co.uk THE EDITORIAL TEAM WISH ALL OUR READERS A PEACEFUL CHRISTMAS AND A HEALTHY AND HAPPY NEW YEAR Editorial Team Date for copy- Feb/March 2013 edition is 8th January 2013 Editor…Pauline Verbe [email protected] 01491 614350 Sub Editor...Ozanna Duffy [email protected] 01491 612859 St.Leonard’s Church News [email protected] 01491 614543 Val Kearney Advertising Manager [email protected] 01491 614989 Helen Wiedemann Front Cover Designer www.aplusbstudio.com Benji Wiedemann Printer Simon Williams [email protected] 07919 891121 3 The Minister Writes “It’s the lights that get me in the end. The candlelight bouncing off the oh-so-carefully polished glasses on the table; the dim amber glow from the oven that silhouettes the golden skin of the roasting bird; the shimmering string of lanterns I weave through the branches of the tree. -

Aston Rowant & Lewknor Speed Limits

OXFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL (ASTON ROWANT, LEWKNOR AND OTHER PARISHES) (SPEED LIMITS) ORDER 20** The Oxfordshire County Council, in exercise of its powers under Section 84 and Part IV of Schedule 9 to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (“the Act”) and of all other enabling powers and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to that Act, hereby makes the following Order. 1. This Order may be cited as the Oxfordshire County Council (Aston Rowant, Lewknor and Other Parishes) (Speed Limits) Order 20** and shall come into force on the day of 20**. 2. No person shall drive any vehicle at a speed in excess of 30 miles per hour in any of the lengths of road specified in Schedule 1 to this Order. 3. No person shall drive any vehicle at a speed in excess of 40 miles per hour in any of the lengths of road specified in Schedule 2 to this Order. 4. No person shall drive any vehicle at a speed in excess of 50 miles per hour in any of the lengths of road specified in Schedule 3 to this Order. 5. No speed limit imposed by this Order applies to a vehicle falling within Regulation 3(4) of the Road Traffic Exemptions (Special Forces) (Variation and Amendment) Regulations 2011, being a vehicle used for naval, military or air force purposes, when used in accordance with regulation 3(5) of those regulations. 6. The Oxfordshire County Council (Aston Rowant and Lewknor Area) (Speed Limits) Order 2011 is hereby revoked. -

Historic Urban Character Area 12: Castle and Periphery- Oxford Castle

OXFORD HISTORIC URBAN CHARACTER ASSESSMENT HISTORIC URBAN CHARACTER AREA 12: CASTLE AND PERIPHERY- OXFORD CASTLE The HUCA is located within broad character Zone D: Castle and periphery. The broad character zone is defined by the extent of the Norman castle defences and includes part of the former canal basin located to the north. Summary characteristics • Dominant period: Mixture of medieval, post-medieval and modern. • Designations: Oxford Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument (County No 21701). Two Grade I, three Grade II*, eight Grade II listings. Central Conservation Area. • Archaeological Interest: Potential for further Late Saxon, Norman, medieval, post-medieval remains and later prison remains. Specific features of note include the remains of the Saxon street grid, settlement and defences, the Norman and later castle precinct, defences, Church of St Budoc and the Collegiate Chapel of St George. The area also includes the site of the medieval Shire Court and the 18th century prison complex. The area has exceptional potential for well preserved waterlogged remains and for human burials of Saxon, medieval and post-medieval date including the remains of prisoners thrown into the castle ditch. The built fabric of medieval well house, the St Georges Tower, the 12th rebuilt crypt of the Collegiate Chapel and the 18th century prison are also of notable interest. • Character: Modern leisure, retail and heritage complex of stone built structures carefully integrated with medieval and post-medieval fabric of the motte, St Georges Tower and the 18th century prison. • Spaces: The site contains a series of paved yards and squares which utilise historic spaces and allow public access through the complex. -

Goring (July 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Landownership • P

VCH Oxfordshire • Texts in Progress • Goring (July 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Landownership • p. 1 VCH Oxfordshire Texts in Progress Goring Landownership In the mid-to-late Anglo-Saxon period Goring may have been the centre of a sizeable royal estate, parts of which became attached to the burh of Wallingford (Berks.) following its creation in the late 9th century.1 By 1086 there were three estates in the parish, of which two can be identified as the later Goring and Gatehampton manors.2 Goring priory (founded before 1135) accrued a separate landholding which became known as Goring Priory manor, while the smaller manors of Applehanger and Elvendon developed in the 13th century from freeholds in Goring manor’s upland part, Applehanger being eventually absorbed into Elvendon. Other medieval freeholds included Haw and Querns farms and various monastic properties. In the 17th century Goring Priory and Elvendon manors were absorbed into a large Hardwick estate based in neighbouring Whitchurch, and in the early 18th Henry Allnutt (d. 1725) gave Goring manor as an endowment for his new Goring Heath almshouse. Gatehampton manor, having belonged to the mostly resident Whistler family for almost 200 years, became attached c.1850 to an estate focused on Basildon Park (Berks.), until the latter was dispersed in 1929−30 and Gatehampton manor itself was broken up in 1943. The Hardwick estate, which in 1909 included 1,505 a. in Goring,3 was broken up in 1912, and landownership has since remained fragmented. Significant but more short-lived holdings were amassed by John Nicholls from the 1780s, by the Gardiners of Whitchurch from 1819, and by Thomas Fraser c.1820, the first two accumulations including the rectory farm and tithes. -

The Hidation of Buckinghamshire. Keith Bailey

THE HIDA TION OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE KEITH BAILEY In a pioneering paper Mr Bailey here subjects the Domesday data on the hidation of Buckinghamshire to a searching statistical analysis, using techniques never before applied to this county. His aim is not explain the hide, but to lay a foundation on which an explanation may be built; to isolate what is truly exceptional and therefore calls for further study. Although he disclaims any intention of going beyond analysis, his paper will surely advance our understanding of a very important feature of early English society. Part 1: Domesday Book 'What was the hide?' F. W. Maitland, in posing purposes for which it may be asked shows just 'this dreary old question' in his seminal study of how difficult it is to reach a consensus. It is Domesday Book,1 was right in saying that it almost, one might say, a Holy Grail, and sub• is in fact central to many of the great questions ject to many interpretations designed to fit this of early English history. He was echoed by or that theory about Anglo-Saxon society, its Baring a few years later, who wrote, 'the hide is origins and structures. grown somewhat tiresome, but we cannot well neglect it, for on no other Saxon institution In view of the large number of scholars who have we so many details, if we can but decipher have contributed to the subject, further discus• 2 them'. Many subsequent scholars have also sion might appear redundant. So it would be directed their attention to this subject: A. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Wessex and the Reign of Edmund Ii Ironside

Chapter 16 Wessex and the Reign of Edmund ii Ironside David McDermott Edmund Ironside, the eldest surviving son of Æthelred ii (‘the Unready’), is an often overlooked political figure. This results primarily from the brevity of his reign, which lasted approximately seven months, from 23 April to 30 November 1016. It could also be said that Edmund’s legacy compares unfavourably with those of his forebears. Unlike other Anglo-Saxon Kings of England whose lon- ger reigns and periods of uninterrupted peace gave them opportunities to leg- islate, renovate the currency or reform the Church, Edmund’s brief rule was dominated by the need to quell initial domestic opposition to his rule, and prevent a determined foreign adversary seizing the throne. Edmund conduct- ed his kingship under demanding circumstances and for his resolute, indefati- gable and mostly successful resistance to Cnut, his career deserves to be dis- cussed and his successes acknowledged. Before discussing the importance of Wessex for Edmund Ironside, it is con- structive, at this stage, to clarify what is meant by ‘Wessex’. It is also fitting to use the definition of the region provided by Barbara Yorke. The core shires of Wessex may be reliably regarded as Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berk- shire and Hampshire (including the Isle of Wight).1 Following the victory of the West Saxon King Ecgbert at the battle of Ellendun (Wroughton, Wilts.) in 835, the borders of Wessex expanded, with the counties of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Essex passing from Mercian to West Saxon control.2 Wessex was not the only region with which Edmund was associated, and nor was he the only king from the royal House of Wessex with connections to other regions. -

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxons Britain looked very different when the Anglo-Saxons came to our shores over 1600 years ago! Much of the country was covered in oak forests and many of the population lived in the countryside where they made a living from farming. Use the links below to find out more about this era in Britain’s history. Who were the Anglo-Saxons? Why and when did they come to Britain? https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zxsbcdm/arti cles/zq2m6sg https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zxsbcdm/a rticles/z23br82 http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/interactive/timelines/l anguage_timeline/index_embed.shtml Use this link to look at some of the different groups / tribes who were https://www.natgeokids.com/uk/discover/history/gen eral-history/anglo-saxons/ fighting and living in Britain during the AD 400s and why they came to Britain. The Anglo-Saxons were a mix of tribes from areas of Europe that settled in Where did Anglo-Saxons live? What Britain from around AD 410 to 1066. were their settlements like? http://www.primaryhomeworkhelp.co.uk/saxons/se ttle.htm What did Anglo-Saxon life look like? Who was in charge? https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/clips/znjqxnb https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zxsbcdm/arti We have set you some activities on cles/zqrc9j6 Purple Mash which may also help you Use the interactive image to find out build a picture in your head about about the different roles people had in what Anglo-Saxon Britain looked like. Anglo-Saxon society including the king, thegn (sometimes spelt ‘thane’), ceorl Sutton Hoo Burial Artefacts (pronounced ‘churl’) and slaves. -

Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2020-2035

CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version 1 Cover picture: Riverside Meadows Local Green Space (Policy CRP 6) 2 CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 6 • The Parish Vision • Objectives of the Plan 2. The neighbourhood area 10 3. Planning policy context 21 4. Community views 24 5. Land use planning policies 27 • Policy CRP1: Village boundaries and infill development • Policy CRP2: Housing mix and tenure • Policy CRP3: Land at Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford • Policy CRP4: Conservation of the environment • Policy CRP5: Protection and enhancement of ecology and biodiversity • Policy CRP6: Green spaces 6. Implementation 42 Crowmarsh Parish Council January 2021 3 List of Figures 1. Designated area of Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2. Schematic cross-section of groundwater flow system through Crowmarsh Gifford 3. Location of spring line and main springs 4. Environment Agency Flood risk map 5. Chilterns AONB showing also the Ridgeway National Trail 6. Natural England Agricultural Land Classification 7. Listed buildings in and around Crowmarsh Parish 8. Crowmarsh Gifford and the Areas of Natural Outstanding Beauty 9. Policies Map 9A. Inset Map A Crowmarsh Gifford 9B. Insert Map B Mongewell 9C. Insert Map C North Stoke 4 List of Appendices* 1. Baseline Report 2. Environment and Heritage Supporting Evidence 3. Housing Needs Assessment 4. Landscape Survey and Impact Assessment 5. Site Assessment Crowmarsh Gifford 6. Strategic Environment Assessment 7. Consultation Statement 8. Compliance Statement * Issued as a set of eight separate documents to accompany the Plan 5 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Neighbourhood Plans are a recently introduced planning document subsequent to the Localism Act, which came into force in April 2012. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Timetables: South Oxfordshire Bus Services

Drayton St Leonard - Appleford - Abingdon 46 Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays Drayton St Leonard Memorial 10.00 Abingdon Stratton Way 12.55 Berinsfield Interchange west 10.05 Abingdon Bridge Street 12.56 Burcot Chequers 10.06 Culham The Glebe 13.01 Clifton Hampden Post Office 10.09 Appleford Carpenters Arms 13.06 Long Wittenham Plough 10.14 Long Wittenham Plough 13.15 Appleford Carpenters Arms 10.20 Clifton Hampden Post Office 13.20 Culham The Glebe 10.25 Burcot Chequers 13.23 Abingdon War Memorial 10.33 Berinsfield Interchange east 13.25 Abingdon Stratton Way 10.35 Drayton St Leonard Memorial 13.30 ENTIRE SERVICE UNDER REVIEW Oxfordshire County Council Didcot Town services 91/92/93 Mondays to Saturdays 93 Broadway - West Didcot - Broadway Broadway Market Place ~~ 10.00 11.00 12.00 13.00 14.00 Meadow Way 09.05 10.05 11.05 12.05 13.05 14.05 Didcot Hospital 09.07 10.07 11.07 12.07 13.07 14.07 Freeman Road 09.10 10.10 11.10 12.10 13.10 14.10 Broadway Market Place 09.15 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ Broadway, Park Road, Portway, Meadow Way, Norreys Road, Drake Avenue, Wantage Road, Slade Road, Freeman Road, Brasenose Road, Foxhall Road, Broadway 91 Broadway - Parkway - Ladygrove - The Oval - Broadway Broadway Market Place 09.15 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 Orchard Centre 09.17 10.17 11.17 12.17 13.17 14.17 Didcot Parkway 09.21 10.21 11.21 12.21 13.21 14.21 Ladygrove Trent Road 09.25 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 Ladygrove Avon Way 09.29 10.29 11.29 12.29 13.29 14.29 The Oval 09.33 10.33 11.33 12.33 13.33 14.33 Didcot Parkway 09.37 -

Getting to Know Your River

Would you like to find out more about us, or about your environment? Then call us on 08708 506 506 (Mon-Fri 8-6) A user’s guide to the email River Thames enquiries@environment- agency.gov.uk or visit our website www.environment-agency.gov.uk incident hotline getting to know 0800 80 70 60 (24hrs) floodline 0845 988 1188 your river Environment first: This publication is printed on paper made from 100 per cent previously used waste. By-products from making the pulp and paper are used for composting and fertiliser, for making cement and for generating energy. GETH0309BPGK-E-P Welcome to the River Thames safe for the millions of people who use it, from anglers and naturalists to boaters, We are the Environment Agency, navigation authority for the River Thames walkers and cyclists. This leaflet is an essential guide to helping the wide variety from Lechlade to Teddington. We care for the river, keeping it clean, healthy and of users enjoy their activities in harmony. To help us maintain this harmony, please To encourage better understanding amongst river users, there are nine River User Groups (RUGs) read about activities other than your own covering the length of the river from Cricklade to to help you appreciate the needs of others. Tower Bridge. Members represent various river users, from clubs and sporting associations to commercial businesses. If you belong to a club that uses the river, encourage it to join the appropriate group. Contact your local waterway office for details. Find out more about the River Thames at www.visitthames.co.uk Before you go..