Prospects for Peace in Sudan Briefing February 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Commission and Sudanese Authorities Sign the Country Strategy Paper to Resume Co- Operation

IP/05/94 Brussels, 25 January 2005 European Commission and Sudanese authorities sign the Country Strategy Paper to resume co- operation Following the signature of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the Government of the Sudan and the SPLM/A in Nairobi on 9 January 2005, the European Commission and the Government of the Sudan have finalised the Country Strategy Paper (CSP) for their cooperation. This document includes the National Indicative Programme and will be signed at 15h30 on 25 January 2005 by the Minister for International Co-operation, Mr. Takana, and the European Commissioner for Development, Mr. L. Michel. The President of the European Commission, Mr. J.M. Barroso, the Vice-president of the Sudan, Mr. Taha and Mr. Nhial Deng Nhial, Commissioner for External relations of the SPLM, will witness the signature. In November 1999, after 9 years of suspension of co-operation, the EU and the Sudan engaged in a formal Political Dialogue. Since December 2001, the Dialogue has been intensified with a view to a gradual resumption of co-operation once a Comprehensive Peace Agreement would be signed. The European Union has been clearly linking its future relations with the Sudan to the signing of a Comprehensive Peace Agreement. The Agreement is considered in particular as a basis to integrate in a global process the other marginalised areas of Sudan, including Darfur. The signature of the CSP should be considered a first step to normalise the Commisison’s relations with the Government of the Sudan. Its implementation will be gradual and in parallel to the effective implementation of the peace agreement and the improvement of the situation in the Darfur. -

South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’S Newest Country

The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs July 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41900 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Summary In January 2011, South Sudan held a referendum to decide between unity or independence from the central government of Sudan as called for by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended the country’s decades-long civil war in 2005. According to the South Sudan Referendum Commission (SSRC), 98.8% of the votes cast were in favor of separation. In February 2011, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir officially accepted the referendum result, as did the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, the United States, and other countries. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan is to officially declare its independence. The Obama Administration welcomed the outcome of the referendum and pledged to recognize South Sudan as an independent country in July 2011. The Administration is expected to send a high-level presidential delegation to South Sudan’s independence celebration on July 9, 2011. A new ambassador is also expected to be named to South Sudan. South Sudan faces a number of challenges in the coming years. Relations between Juba, in South Sudan, and Khartoum are poor, and there are a number of unresolved issues between them. The crisis in the disputed area of Abyei remains a contentious issue, despite a temporary agreement reached in mid-June 2011. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

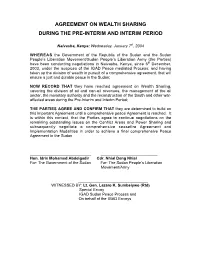

Agreement on Wealth Sharing During the Pre-Interim and Interim Period

AGREEMENT ON WEALTH SHARING DURING THE PRE-INTERIM AND INTERIM PERIOD Naivasha, Kenya: Wednesday, January 7th, 2004 WHEREAS the Government of the Republic of the Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Sudan People’s Liberation Army (the Parties) have been conducting negotiations in Naivasha, Kenya, since 6th December, 2003, under the auspices of the IGAD Peace mediated Process; and having taken up the division of wealth in pursuit of a comprehensive agreement, that will ensure a just and durable peace in the Sudan; NOW RECORD THAT they have reached agreement on Wealth Sharing, covering the division of oil and non-oil revenues, the management of the oil sector, the monetary authority and the reconstruction of the South and other war- affected areas during the Pre-Interim and Interim Period; THE PARTIES AGREE AND CONFIRM THAT they are determined to build on this important Agreement until a comprehensive peace Agreement is reached. It is within this context, that the Parties agree to continue negotiations on the remaining outstanding issues on the Conflict Areas and Power Sharing and subsequently negotiate a comprehensive ceasefire Agreement and Implementation Modalities in order to achieve a final comprehensive Peace Agreement in the Sudan. ____________________________ __________________________ Hon. Idris Mohamed Abdelgadir Cdr. Nhial Deng Nhial For: The Government of the Sudan For: The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army ________________________________ WITNESSED BY: Lt. Gen. Lazaro K. Sumbeiywo (Rtd) Special Envoy IGAD -

Republic of South Sudan Ministry of Foreign Affairs & International Cooperation Headquarters

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS & INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION HEADQUARTERS- STATEMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN ON EFFORTS TO ACHIEVE UNIVERSALITY OF THE BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION (BWC) Delivered by the Director General for International Cooperation, Ambassador Moses Akol Ajawin, to the MEETING OF STATE PARTIES TO BIOLOGICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION Tuesday, 4th December 2018 United Nations Geneva, Switzerland 0 In the field of biological weapons, there is almost no prospect of detecting a pathogen until it has been used in an attack. ---Barton Gellman Mr. Gjorjinisky, Chairman of the 2018 Annual Meeting of State Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention Distinguished delegates, Ladies and gentlemen, A very good afternoon to you! On behalf of my country, its people, our president Salva Kiir Mayardit, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation Honorable Nhial Deng Nhial, my colleague Honorable Dr. Alma Jervase Yak, chairperson of the Sub-committee on Bilateral Relations in the Transitional National Legislative Assembly and member of Parliamentarians for Global Action, and on my own behalf, kindly allow me to express great appreciation to the organizers for affording the Republic of South Sudan an opportunity to attend and address this august meeting of state parties to the Biological Weapons Convention in this beautiful city. I would equally wish to profoundly thank the Peace and Democracy Program of Parliamentarians for Global Action and its director without whose magnanimous support the South Sudanese delegation would not have been able to attend this important annual gathering. I would also like to thank state parties to the Biological Weapons convention for kindly allowing our delegation to intrude into one of their most important annual events. -

What Happened at Wunlit? an Oral History of the 1999 Wunlit Peace Conference

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT WHAT HAPPENED AT WUNLIT? AN ORAL HISTORY OF THE 1999 WUNLIT PEACE CONFERENCE SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT What Happened at Wunlit? An oral history of the 1999 Wunlit Peace Conference Authors Compiled and edited by John Ryle and Douglas H. Johnson Research conducted by Alier Makuer Gol, Chirrilo Madut Anei, Elizabeth Nyibol Malou, James Gatkuoth Mut Gai, Jedeit Jal Riek, John Khalid Mamun Margan, Machot Amuom Malou, Malek Henry Chuor, Mawal Marko Gatkuoth. Supported by John Ryle and Loes Lijnders. Published in 2021 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the under- standing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI SOUTH SUDAN HEAD OF OFFICE: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS MANAGER: Magnus Taylor SSCA LEAD RESEARCHER: John Ryle, Legrand Ramsey Professor of Anthropology, Bard College, New York RVI PROGRAMME OFFICER, SOUTH SUDAN: Mimi Bor DESIGN: Lucy Swan MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-57-9 RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2021 Cover and back cover images © Bill Lowrey Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

Advance Version Distr.: Restricted 10 March 2016

A/HRC/31/CRP.6 Advance version Distr.: Restricted 10 March 2016 English only Human Rights Council Thirty-first session Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Assessment mission by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to improve human rights, accountability, reconciliation and capacity in South Sudan: detailed findings* Summary This present document contains the detailed findings of the comprehensive assessment conducted by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) into allegations of violations and abuses of human rights and violations of international humanitarian law in South Sudan since the outbreak of violence in December 2013. It should be read in conjunction with the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the assessment mission to South Sudan submitted to the Human Rights Council at its thirty-first session (A/HRC/31/49). * Reproduced as received. A/HRC/31/CRP.6 Contents Page Part 1 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 6 I. Establishment of the OHCHR Assessment Mission to South Sudan ............................................... 8 A. Mandate ................................................................................................................................... 8 B. Methodology ........................................................................................................................... -

The Case of South Sudan

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Theses Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-20-2020 Conflict of a Nation, and Repatriation in Collapsed States: The Case of South Sudan Emmanuel Bakheit [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, International Relations Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Social Justice Commons Recommended Citation Bakheit, Emmanuel, "Conflict of a Nation, and Repatriation in Collapsed States: The Case of South Sudan" (2020). Master's Theses. 1343. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1343 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conflict of a Nation, and Repatriation in Collapsed States: The Case of South Sudan 1 Table of Contents: Part I 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 2. Structural order of society………………………….............................................. 3. Ominous ethnic organization within state structures that emulate functions:………………………………………………………………………….. ……………………………………………………………………………………… 4. Adoption of national ethnos…………………………………………………....... -

South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT FRIDAY, 05 JULY 2013 SOUTH SUDAN • UN peacekeeping chief arrives in Juba (Gurtong) • Media Bills shall be passed before second Independence Anniversary (Gurtong) • VP Machar speaks on hopes to lead South Sudan (Sudantribune.com) • South Sudan in talks with Yauyau rebels to end conflict (Sudantribune.com) • SPLA tightens security nation-wide ahead of independence anniversary (Eye Radio) • Police say 200 criminals arrested in June (Sudantribune.com) • South Sudan and DRC bordering states sign cooperation agreement (Sudantribune.com) • Immigration department tightens rules on foreigners (Eye Radio) • No deliberate target against Ugandans, says Juba minister (The Daily Monitor) • UNMISS Korean engineers upgrade infrastructure in Jonglei (Gurtong) • Authorities threaten to seize cattle in streets (Radio Miraya) • New oil refinery not yet functional – Unity State (Eye Radio) • Government to launch airport construction (Gurtong) SOUTH SUDAN, SUDAN • AU summons foreign ministers Nhial Deng and Ali Karti (Eye Radio) • South Sudan accuses Khartoum of new attacks on its territories (Sudantribune.com) • August arrival of first UN troops for Sudan’s border (Agence France-Presse) OTHER HIGHLIGHTS • Curfew imposed in South Darfur capital after deadly clashes with tribal militias (Sudantribune.com ) COMMENTS/ STATEMENTS • “Failed state status” overshadows the country’s second Independence Anniversary (By Justin Ambago Ramba on SouthSudanNation.com) • Two years old but nothing to celebrate (By Simon Tisdall on The Guardian) • Challenge of disarming a nation when no one trusts the state (By Simon Tisdall on The Guardian) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMISS Communications & Public Information Office can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan. -

National Platform

Date: 17/04/2014 Press Statement for Immediate Release...... NPPR meets Government Delegation to Addis Ababa Peace Talks CAPTION: Archbishop Daniel Deng (L) speaking during the meeting while the Government Chief Negotiator Hon. Nhial Deng Nhial (R) looks on. (PHOTO BY: Peter Kuot) JUBA: Members of the recently launched National Platform for Peace and Reconciliation (NPPR) today met with the Government Delegation to the Peace talks in Addis Ababa at the Parliamentary Affairs offices in Juba in a bid to urge the government side to embrace peaceful negotiations as the only way to end the current crisis. Archbishop Daniel Deng, Hon. Chuol Rambang and Hon. David Okweir who respectively chairs the three peace and reconciliation bodies namely the Committee for National Healing Peace and Reconciliation (CNHPR), South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission (SSPRC) and Specialized Committee on Peace and Reconciliation in the National Legislative Assembly (SCPR/NLA) led the NPPR team that included representatives from the Civil Society and the church to a round-table meeting with members of the delegation led by Hon. Nhial Deng Nhial who is the Chief negotiator and his deputy Hon. Michael Makuei Lueth who is also the national Minister of Information and Broadcasting. NPPR which is a union of the three main peace and reconciliation bodies joined by other civil society organizations and the church convened this meeting with the government delegation ahead of the next round of talks scheduled to take place from 22nd April, to press the government side to go to the talks with the spirit of dialogue as the only solution to the conflict. -

Communiqué of the 68Th Extra-Ordinary Session of Igad Council of Ministers on Situation in the Sudan and the Status of the South Sudan Peace Process

COMMUNIQUÉ OF THE 68TH EXTRA-ORDINARY SESSION OF IGAD COUNCIL OF MINISTERS ON SITUATION IN THE SUDAN AND THE STATUS OF THE SOUTH SUDAN PEACE PROCESS 19TH JUNE 2019 ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA The IGAD Council of Ministers held its 68th Extra-Ordinary Session on 19 June 2019 in Addis Ababa under the chairmanship of H.E. Gedu Andargachew, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and Chairperson of the IGAD Council of Ministers. The session was attended by H.E. Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Djibouti; H.E. Dr Monica Juma, Cabinet Secretary for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kenya; H.E. Ahmed Isse Awad, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Somalia; H.E. Nhial Deng Nhial, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of South Sudan; H.E. Amb. Elham Ibrahim Ahmed, Acting Foreign Minister of the Republic of the Sudan, H.E. Henry Okello Oryem, State Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Uganda; H.E. Hirut Zemene, State Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; and H.E. Amb. Tom Amolo, Political and Diplomatic Secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kenya; H.E. Siraj Fegessa, IGAD Director for Peace and Security on behalf of H.E. Mahboub Maalim, IGAD Executive Secretary; H.E. Amb. Abdoulaye Diop, Chief of Staff in the Bureau of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission (AUC), H.E. Dr Ismael Wais, IGAD Special Envoy for South Sudan; H.E. -

Press Release

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office PRESS RELEASE Juba, 4 June, 2013 UN UNDER-SECRETARY-GENERAL FOR PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS TO VISIT SOUTH SUDAN Herve Ladsous, the United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations will travel to South Sudan for a three-day visit starting on Friday 5 July. This visit will enable Herve Ladsous to take stock of progress, achievements and challenges encountered by South Sudan and the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) in the past 12 months. As part of a broader interaction with the UN peacekeeping missions in the region, the USG will also meet with the Head of Mission/Force Commander of the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA) to get an overview of UNISFA's mandate implementation, its accomplishments and challenges. In Juba, Herve Ladsous is scheduled to meet with the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir Mayardit, the Vice-President of South Sudan, Riek Machar Teny, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Nhial Deng Nhial, the Minister of Interior, Alison Manani Magaya, the Minister of Defence and Veteran Affairs, John Kong Nyuon, and the Chief of General Staff of the SPLA, General James Hoth Mai as well as members of the foreign diplomatic corps, UNMISS civilian and military staff. Under-Secretary-General Ladsous will also travel to Jonglei State to assess current conditions on the ground affecting the implementation of the UNMISS mandate to protect civilians. When in Bor, the state capital, he will meet with local authorities including the Governor of Jonglei Kuol Manyang Juuk, as well as UNMISS staff and military peacekeeping contingents.