Why Does Earth's Crust Move?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of a Heterogeneous Martian Mantle: Clues from K, P, Ti, Cr, and Ni Variations in Gusev Basalts and Shergottite Meteorites

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 296 (2010) 67–77 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl The evolution of a heterogeneous Martian mantle: Clues from K, P, Ti, Cr, and Ni variations in Gusev basalts and shergottite meteorites Mariek E. Schmidt a,⁎, Timothy J. McCoy b a Dept. of Earth Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada L2S 3A1 b Dept. of Mineral Sciences, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0119, USA article info abstract Article history: Martian basalts represent samples of the interior of the planet, and their composition reflects their source at Received 10 December 2009 the time of extraction as well as later igneous processes that affected them. To better understand the Received in revised form 16 April 2010 composition and evolution of Mars, we compare whole rock compositions of basaltic shergottitic meteorites Accepted 21 April 2010 and basaltic lavas examined by the Spirit Mars Exploration Rover in Gusev Crater. Concentrations range from Available online 2 June 2010 K-poor (as low as 0.02 wt.% K2O) in the shergottites to K-rich (up to 1.2 wt.% K2O) in basalts from the Editor: R.W. Carlson Columbia Hills (CH) of Gusev Crater; the Adirondack basalts from the Gusev Plains have more intermediate concentrations of K2O (0.16 wt.% to below detection limit). The compositional dataset for the Gusev basalts is Keywords: more limited than for the shergottites, but it includes the minor elements K, P, Ti, Cr, and Ni, whose behavior Mars igneous processes during mantle melting varies from very incompatible (prefers melt) to very compatible (remains in the shergottites residuum). -

Thermal and Crustal Evolution of Mars Steven A

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. E7, 10.1029/2001JE001801, 2002 Thermal and crustal evolution of Mars Steven A. Hauck II1 and Roger J. Phillips McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences and Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA Received 11 October 2001; revised 4 February 2002; accepted 11 February 2002; published 16 July 2002. [1] We present a coupled thermal-magmatic model for the evolution of Mars’ mantle and crust that may be consistent with estimates of the average crustal thickness and crustal growth rate. By coupling a simple parameterized model of mantle convection to a batch- melting model for peridotite, we can investigate potential conditions and evolutionary paths of the crust and mantle in a coupled thermal-magmatic system. On the basis of recent geophysical and geochemical studies, we constrain our models to have average crustal thicknesses between 50 and 100 km that were mostly formed by 4 Ga. Our nominal model is an attempt to satisfy these constraints with a relatively simple set of conditions. Key elements of this model are the inclusion of the energetics of melting, a wet (weak) mantle rheology, self-consistent fractionation of heat-producing elements to the crust, and a near- chondritic abundance of those elements. The latent heat of melting mantle material is a small (percent level) contributor to the total planetary energy budget over 4.5 Gyr but is crucial for constraining the thermal and magmatic history of Mars. Our nominal model predicts an average crustal thickness of 62 km that was 73% emplaced by 4 Ga. -

INTERIOR of the EARTH / an El/EMEI^TARY Xdescrrpntion

N \ N I 1i/ / ' /' \ \ 1/ / / s v N N I ' / ' f , / X GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 / N X \ i INTERIOR OF THE EARTH / AN El/EMEI^TARY xDESCRrPNTION The Interior of the Earth An Elementary Description By Eugene C. Robertson GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 Washington 1966 United States Department of the Interior CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary Geological Survey H. William Menard, Director First printing 1966 Second printing 1967 Third printing 1969 Fourth printing 1970 Fifth printing 1972 Sixth printing 1976 Seventh printing 1980 Free on application to Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Abstract ......................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................... 1 Surface observations .............................................. 1 Openings underground in various rocks .......................... 2 Diamond pipes and salt domes .................................. 3 The crust ............................................... f ........ 4 Earthquakes and the earth's crust ............................... 4 Oceanic and continental crust .................................. 5 The mantle ...................................................... 7 The core ......................................................... 8 Earth and moon .................................................. 9 Questions and answers ............................................. 9 Suggested reading ................................................ 10 ILLUSTRATIONS -

The Earth's Crust Is Like the Skin of an Apple

The Earth’s Crust Weathering & Erosion ! " Soil begins with rocks – so how is rock turned into soil? ! " How does soil travel and move? ! " Without sediments our planet would decline, perhaps ceasing to exist Inside the Earth The Earth's Crust is like the skin of an apple. It is very thin in comparison to the other three layers. The crust is only about 3-5 miles (8 kilometers) thick under the oceans(oceanic crust) and about 25 miles (32 kilometers) thick under the continents (continental crust). The temperatures of the crust vary from air temperature on top to about 1600 degrees Fahrenheit (870 degrees Celcius) in the deepest parts of the crust Three Laws of Thermodynamics ! " The first law of thermodynamics, also called conservation of energy, states that the total amount of energy in the universe is constant. This means that all of the energy has to end up somewhere, either in the original form or in a different from. We can use this knowledge to determine the amount of energy in a system, the amount lost as waste heat, and the efficiency of the system. ! " The second law of thermodynamics states that the disorder in the universe always increases. After cleaning your room, it always has a tendency to become messy again. This is a result of the second law. As the disorder in the universe increases, the energy is transformed into less usable forms. Thus, the efficiency of any process will always be less than 100%. ! " The third law of thermodynamics tells us that all molecular movement stops at a temperature we call absolute zero, or 0 Kelvin (-273oC). -

Tectonics and Crustal Evolution

Tectonics and crustal evolution Chris J. Hawkesworth, Department of Earth Sciences, University peaks and troughs of ages. Much of it has focused discussion on of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, the extent to which the generation and evolution of Earth’s crust is UK; and Department of Earth Sciences, University of St. Andrews, driven by deep-seated processes, such as mantle plumes, or is North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK, c.j.hawkesworth@bristol primarily in response to plate tectonic processes that dominate at .ac.uk; Peter A. Cawood, Department of Earth Sciences, University relatively shallow levels. of St. Andrews, North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK; and Bruno The cyclical nature of the geological record has been recog- Dhuime, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills nized since James Hutton noted in the eighteenth century that Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK even the oldest rocks are made up of “materials furnished from the ruins of former continents” (Hutton, 1785). The history of ABSTRACT the continental crust, at least since the end of the Archean, is marked by geological cycles that on different scales include those The continental crust is the archive of Earth’s history. Its rock shaped by individual mountain building events, and by the units record events that are heterogeneous in time with distinctive cyclic development and dispersal of supercontinents in response peaks and troughs of ages for igneous crystallization, metamor- to plate tectonics (Nance et al., 2014, and references therein). phism, continental margins, and mineralization. This temporal Successive cycles may have different features, reflecting in part distribution is argued largely to reflect the different preservation the cooling of the earth and the changing nature of the litho- potential of rocks generated in different tectonic settings, rather sphere. -

LESSON PLAN from Core to Crust Craters of the Moon National Monument & Preserve

LESSON PLAN From Core to Crust Craters of the Moon National Monument & Preserve Side view of mantle and crust GRADE LEVEL: Fifth Grade-Sixth Grade SUBJECT: Earth Science, Geology DURATION: 2-3 hours GROUP SIZE: Up to 36 (6-12 breakout groups) SETTING: classroom NATIONAL/STATE STANDARDS: CCRA.SL.1 NGSS.SEP.2 KEYWORDS: stratigraphy, earth science, geology Overview Students act out different parts of the Earth and then build models of the Earth showing its layers. (CLASSROOM ACTIVITY) Objective(s) Students will be able to name the parts of the Earth. Students will understand that the Earth is dynamic. Background The Earth, like the life on its surface, is changing all the time. Parts of it are molten and slowly rise, cool, and sink back toward the Earth's core, like soup simmering over a fire. Continents drift around the globe creating the features we think of when we think of geology. But most of the Earth lies unseen between our feet and the other side of the world. The Earth is made up of the crust, the mantle, and the core. Although geologists have only drilled a few miles into the Earth's crust, they have indirectly deduced much about the remainder of the planet's composition. The Crust What we walk on and see is the crust. It is wafer thin, only 3 to 22 miles thick. If the Earth were the size of a billiard ball, the crust would be as thick as a postage stamp stuck to its surface (think how thick the membrane of life would be that coats the Earth!). -

Origin and Evolution of Earth Research Questions for a Changing Planet

Origin and Evolution of Earth Research Questions for a Changing Planet Questions about the origins and nature of Earth have long preoccupied human thought and the scientific endeavor. Deciphering the planet’s history and processes could improve the abil- ity to predict catastrophes like earthquakes and volcanoes, to manage Earth’s resources, and to anticipate changes in climate and geologic processes. This report captures, in a series of questions, the essential scientific challenges that constitute the frontier of Earth science at the start of the 21st century. arth is an active place. Earthquakes rip along plate boundaries, volcanoes spew fountains of Emolten lava, and mountain ranges and seabed are constantly created and destroyed. Earth scientists have long been concerned with deciphering the history—and predicting the future—of this active planet. Over the past four decades, Earth scientists have made great strides in understanding Earth’s workings. Scientists have ever-improving tools to understand how Earth’s internal processes shape the planet’s surface, how life can be sustained over billions of years, and how geological, biological, atmospheric, and oceanic NASA/NDGC processes interact to produce climate—and climatic change. At the request of the U.S. Department of Energy, Na- tional Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Science Foundation, and U.S. Geological Survey, the National Research Council assembled a committee to propose and explore grand ques- tions in Earth science. This report, which is the result of the committee’s deliberations and input solicited from the Earth science community, describes ten “big picture” Earth science issues being pursued today. -

Evolution of Early Continental Crust

REVIEW ARTICLE Evolution of early continental crust R. S. Sharma* and M. K. Pandit Department of Geology, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur 302 004, India but we have no direct record of the earth’s first 500 mil- The present article reviews the evolution of continen- lion years of evolution (accepting the age of the earth as tal crust since the time the earth began to inscribe a permanent history in rocks of the cratonic nuclei. The ~ 4.5 Ga). There could have been several reasons which existence of a sialic crust prior to 4200 Ma ago, soon may have destroyed the early crust. These may include after the permobile stage of the earth, is documented rifting, delamination or continental subduction, erosion, by detrital zircon in the Precambrian metacon- covering by younger sediments and even meteorite bom- glomerate of Neyerer Complex, Western Australia. bardment. It should be borne in mind that if the earliest The evolution of Archaean crust (> 2500 Ma) is dis- crust was completely destroyed, the oldest rocks pre- cussed in terms of currently used Nd model-age cal- served now probably represent a fairly advanced stage of culations, based on a depleted mantle evolutionary crustal evolution. model. The model fits the generally accepted assump- tion that LREE depletion of the upper mantle com- menced very early in the earth’s history and that the Features of the Archaean crust present-day MORB is the best representative for the Nd-isotopic composition of today’s depleted mantle. Isotopic and geochemical characteristics of Archaean Finally, the mechanisms for growth or accretion of the crustal rocks (TTG) are characterized by the following continental crust and the incompatibility of thickened features: crust during Archaean time are discussed. -

The Earth's Structure

THE EARTH’S STRUCTURE Geology is the study of the earth, including its structure, rocks, minerals, history, and the forces that affect it. The Earth’s surface has not always had its present form; it has changed over time. The three main layers of the Earth, the crust, mantle, and core, are all made of different materials (Figure 1). The crust is solid rock and can range in thickness from three miles (the ocean floor) to 37 miles (mountain ranges). Project Mohole, began by U.S. scientists in 1959, was designed to drill a hole all the way through the crust into the mantle. The drilling began under the Pacific Ocean, but the project ran out of money and was stopped in 1967. To date, no one has been able to get a sample of material from the mantle, but it is thought to be hotter and denser or heavier than the crust and more plastic or able to flow and change its shape under pressure. The mantle reaches 1800 miles below the crust (84% of the earth’s volume). The core contains more than 15% of the earth’s volume. Many geologists are unwilling to guess what the core is made of, but they think it must be very hot and dense. The earth’s crust is broken into several pieces called plates. These plates rest on and slide across the mantle. These plates are constantly drifting and moving the continents with them. Geologists believe that, millions of years ago, all of the continents were one huge land mass. -

Label and Describe the Earth Diagram

Name_________________________class______ Label and Describe the Earth Diagram Read the definitions then use the information to color code, label and describe IN YOUR OWN WORDS each section of the diagram below. Definitions: crust – (green) the rigid, rocky outer surface of the Earth, composed mostly of basalt and granite. The crust is the thinnest of all layers. It is thicker on continents & thinner under the oceans. inner core – (gray) the solid iron-nickel center of the Earth that is very hot and under great pressure. mantle – (orange) a rocky layer located under the crust - it is composed of silicon, oxygen, magnesium, iron, aluminum, and calcium. Convection (heat) currents carry heat from the hot inner mantle to the cooler outer mantle. outer core – (red) the molten iron-nickel layer that surrounds the inner core. ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ ______________________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________ Name_________________________________cLass________ Label the OUTER LAYERS of the Earth This is a cross section of only the upper layers of the Earth’s surface. Read the definitions below and use the information to locate label and describe IN TWO WORDS the outer layers of the Earth. One has been done for you. continental crust – thick, top Continental Crust – (green) the thick parts of the Earth's crust, not located under the ocean; makes up the comtinents. Oceanic Crust – (brown) thinner more dense parts of the Earth's crust located under the oceans. Ocean – (blue) large bodies of water sitting atop oceanic crust. Lithosphere– (outline in black) made of BOTH the crust plus the rigid upper part of the upper mantle. -

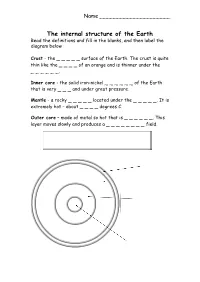

The Internal Structure of the Earth Read the Definitions and Fill in the Blanks, and Then Label the Diagram Below

Name _____________________ The internal structure of the Earth Read the definitions and fill in the blanks, and then label the diagram below Crust - the _ _ _ _ _ surface of the Earth. The crust is quite thin like the _ _ _ _ of an orange and is thinner under the _ _ _ _ _ _. Inner core - the solid iron-nickel _ _ _ _ _ _ of the Earth that is very _ _ _ and under great pressure. Mantle - a rocky _ _ _ _ _ located under the _ _ _ _ _. It is extremely hot – about _ _ _ _ degrees C. Outer core – made of metal so hot that is _ _ _ _ _ _. This layer moves slowly and produces a _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ field. outer layer oceans centre crust hot skin magnetic liquid 5000 Earth’s Structure Worksheet Use information from the following website: to color in the earth and label http://www.learner.org/interactives/dynamicearth/structure.html Earth’s Structure Worksheet Use information from the following website: http://www.learner.org/interactives/dynamicearth/structure.html Label the Layers of the Earth. Write information about each layer in the boxes below. Name: __________________________________________ Date: _______________ Inside Earth WebQuest: Worksheet Introduction: A Webquest is a way for you to explore a topic, such as “The Layers of the Earth” and find useful information to help you understand the topic. In this webquest, you will be visiting web sites that will help you better understand the Earth's interior, continental drift, plate tectonics and how these topics fit together. -

Lithospheric Strength Profiles

21 LITHOSPHERIC STRENGTH PROFILES To study the mechanical response of the lithosphere to various types of forces, one has to take into account its rheology, which means knowing how it flows. As a scientific discipline, rheology describes the interactions between strain, stress and time. Strain and stress depend on the thermal structure, the fluid content, the thickness of compositional layers and various boundary conditions. The amount of time during which the load is applied is an important factor. - At the time scale of seismic waves, up to hundreds of seconds, the sub-crustal mantle behaves elastically down deep within the asthenosphere. - Over a few to thousands of years (e.g. load of ice cap), the mantle flows like a viscous fluid. - On long geological times (more than 1 million years), the upper crust and the upper mantle behave also as thin elastic and plastic plates that overlie an inviscid (i.e. with no viscosity) substratum. The dimensionless Deborah number D, summarized as natural response time/experimental observation time, is a measure of the influence of time on flow properties. Elasticity, plastic yielding, and viscous creep are therefore ingredients of the mechanical behavior of Earth materials. Each of these three modes will be considered in assessing flow processes in the lithosphere; these mechanical attributes are expressed in terms of lithospheric strength. This strength is estimated by integrating yield stress with depth. The current state of knowledge of rock rheology is sufficient to provide broad general outlines of mechanical behavior but also has important limitations. Two very thorny problems involve the scaling of rock properties with long periods and for very large length scales.