ΠΕΔΟМΕΤΡΟΝ Newsletter of the Pedometrics Commission of the IUSS Issue 45, April 2020 from the Chair in This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Für Sonntag, 21

InfoMail 16.04.15: vom Herausgeber signiertes Buch mit BEATLES-Kurzgeschichten /// MACCAZINES /// MANY YEARS AGO InfoMail Donnerstag, 16. April 2015 InfoMails abbestellen oder umsteigen (täglich, wöchentlich oder monatlich): Nur kurze Email schicken. Hallo M.B.M.! Hallo BEATLES-Fan! Ein Buch mit Kurzgeschichten zum Thema BEATLES Weitere Info und/oder bestellen: Einfach Abbildung anklicken Samstag, 1. November 2014: Buch WEIL ICH JOHN LENNON BIN - PHANTASTISCHE BEATLES-GESCHICHTEN. 10,90 € Die von uns verschicken Bücher sind vom Herausgeber signiert. Herausgeber: Bartholomäus Figatowski. Verlag: N. Schmenk. ISBN: 978-3-943022-27-8 Gebundenes Buch; Hochformat 24,6 cm x 17,2 cm; 96 Seiten; Preis: 10.90 €. Inhalt: Wahnfried stellt klar (von Holger Dittmann); Lucy (von Monika Niehaus); Livestream-Liebe (von Holger Mossakowski); Kalte Füße (von Karl-Otto Kaminski); Breaking Eggs (von Rainer Schorm); Operation Samsara (von Katja Göddemeyer); Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Welt (von Raimund Hils); Farbenspiel (von Jörg Weigand); Im Haselbusch (von Renate Schmidt-V.); Gebrochene Flügel (von Detlef Klewer); Picknick am Hügel (von Nina Sträter); Saat des Todes (von Regina Schleheck); Weil ich John Lennon bin (von Holger Dittmann); Die Farbe Gelb (von Marika Bergmann); Als der Regen kam (von Bettina Forbrich); In the Land of Submarines … Nachwort (von Herausgebers Bartholomäus Figatowski); Die Autorinnen und Autoren und ihre Inspirationsquellen. MACCAZINES - TIMELINES Weitere Info und/oder bestellen: Einfach Abbildung anklicken Magazin MACCAZINE - PAUL McCARTNEY TIMELINE 2005. 9,90 € Magazin MACCAZINE - PAUL McCARTNEY TIMELINE 2006. 9,90 € Dutch Paul McCartney Fanclub, Niederlande. Heft; Hochformat: ca. 14,8 cm x ca. 21,0 cm; 28 Seiten; 24 Schwarzweiß-Abbildung; englischsprachig. -

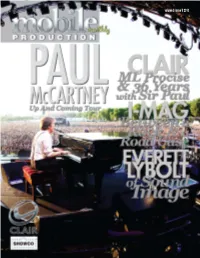

Volume 3 Issue 8 2010 Your Access to Performance with Passion

volume 3 issue 8 2010 Your Access to Performance with Passion. *Sentient Charter is a program of Sentient Jet, LLC (“Sentient”). Sentient arranges flights on behalf of clients with FAR Part 135 air carriers that exercise full operational control of charter flights at all times. Flights will be operated by flights at all times. Flights will be operated by full operational control of charter that exercise air carriers 135 Part flights on behalf of clients with FAR LLC (“Sentient”). Sentient arranges *Sentient Charter is a program of Sentient Jet, details.) for to www.sentient.com/standards standards safety and additional establishedSentient. (Refer by service been certified to provide Sentient and that meet all FAA for that have air carriers 135 Part FAR At Sentient*, we understand that success isn’t something that comes easily. It takes focus, years of preparation and relentless dedication. With an innovative 9-point safety program and a staff of service professionals available 24/7, it’s no wonder that Sentient is the #1 arranger of charter flights in the country. Sentient Charter can take you anywhere on the world’s stage - on the jet you want - at the competitive price you deserve. Sentient Jet is the Proud Platinum Sponsor of the TourLink 2010 Conference Jet Barbeque TO LEARN MORE, PLEASE CONTACT: David Young, Vice President - Entertainment, at [email protected] or 805.899.4747 More than 560 attorneys and advisors in offices across the southeastern U.S. and Washington, D.C., practicing a broad spectrum of business law including transactions, contracts, litigation, transportation and entertainment. -

Aktion "SECOND THINGS"

Alter Markt 12 • 06 108 Halle (Saale) • Telefon 03 45 - 290 390 0 : Di., Mi., Do., Fr., Sa., So. und an Feiertagen jeweils von 10 bis 20 Uhr InfoMail 1449: THINGS 185 & TICKET 99 & "SECOND THINGS" Hallo M.B.M., hallo BEATLES-Fan, in einigen Tagen verschicken wir die neue THINGS-Ausgabe. Als M.B.M. schicken wir Dir Dein THINGS 185 und (falls bei uns abonniert) TICKET 99 automatisch zu. - Aber es gibt auch die neue SECOND THINGS-Aktion. HEFT THINGS 185 (= THINGS+TICKET-Nr. 193). 3,50 Euro Beatles Museum, Deutschland. 1617-8114. Heft; Hochformat A5; 36 Farbseiten; deutschsprachig. Inhalt: Angebot & Information: JOHN LENNON-Caps, -Pins und -Kaffeebecher. Impressum: Informationen zum Beatles Museum und zu THINGS. Im Beatles Museum: McCARTNEY-Signaturen. / Hallo M.B.M.!: Vier große Themen. IT WAS 50 YEARS AGO TODAY - Januar 1961: Die BEATLES werden in Liverpool bekannt. IT WAS 40 YEARS AGO TODAY - Januar 1971: Beginn des Rechtsstreits zwischen PAUL McCARTNEY und LENNON, HARRISON, STARR. IT WAS 30 YEARS AGO TODAY - Januar 1981: JOHN LENNON / YOKO ONO: Veröffentlichung der Single WOMAN / BEAUTIFUL BOYS. IT WAS 20 YEARS AGO TODAY - Januar 1991: PAUL McCARTNEY: Projekt UNPLUGGED - Konzert, Rundfunk- und Fernsehsendungen UNPLUGGED - LP, MC und CDs UNPLUGGED - Weitere UNPLUGGED-Aufnahmen auf Single-CDs, CDs, DVDs, Bootleg-CDs und Bootleg.-DVDs - Weitere UNPLUGGED-Konzerte in Spanien, Großbritannien, Italien und Dänemark. Korrektur & Ergänzung zu IT WAS 10 YEARS AGO TODAY - November 2000: THE BEATLES: Verkaufszahlen vom Album ONE. IT WAS 10 YEARS AGO TODAY - 2001: THE BEATLES & APPLE-Interpreten: Bootleg-CD-Box COMPACT DISC UK SINGLES COLLECTION. -

Bill Harry. "The Paul Mccartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970

Bill Harry. "The Paul McCartney Encyclopedia"The Beatles 1963-1970 BILL HARRY. THE PAUL MCCARTNEY ENCYCLOPEDIA Tadpoles A single by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, produced by Paul and issued in Britain on Friday 1 August 1969 on Liberty LBS 83257, with 'I'm The Urban Spaceman' on the flip. Take It Away (promotional film) The filming of the promotional video for 'Take It Away' took place at EMI's Elstree Studios in Boreham Wood and was directed by John MacKenzie. Six hundred members of the Wings Fun Club were invited along as a live audience to the filming, which took place on Wednesday 23 June 1982. The band comprised Paul on bass, Eric Stewart on lead, George Martin on electric piano, Ringo and Steve Gadd on drums, Linda on tambourine and the horn section from the Q Tips. In between the various takes of 'Take It Away' Paul and his band played several numbers to entertain the audience, including 'Lucille', 'Bo Diddley', 'Peggy Sue', 'Send Me Some Lovin", 'Twenty Flight Rock', 'Cut Across Shorty', 'Reeling And Rocking', 'Searching' and 'Hallelujah I Love Her So'. The promotional film made its debut on Top Of The Pops on Thursday 15 July 1982. Take It Away (single) A single by Paul which was issued in Britain on Parlophone 6056 on Monday 21 June 1982 where it reached No. 14 in the charts and in America on Columbia 18-02018 on Saturday 3 July 1982 where it reached No. 10 in the charts. 'I'll Give You A Ring' was on the flip. -

Paul Mccartney E Brasil: Relação Antiga História Enviado Por: [email protected] Postado Em:23/11/2010

Disciplina - História - Paul McCartney e Brasil: relação antiga História Enviado por: [email protected] Postado em:23/11/2010 Há 20 anos, em abril de 1990, com sua primeira apresentação no país, ele entrou para o livro Guiness dos Recordes. Julia Moreira Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional “É ótimo estar de volta ao Brasil, terra da música linda”, falou Paul McCartney, em português, para os 64 mil fãs que lotaram o estádio do Morumbi (Zona Sul de São Paulo) na noite de domingo (21). O aguardado show do eterno beatle começou com “Venus and Mars/Rock Show” e “Jet”, do Wings, banda que Paul montou depois dos Fab four, e que também contava com a participação da sua então esposa, Linda McCartney (1941-1998), a quem ele dedicou “My Love”. A primeira música do quarteto de Liverpool que o público cantou em uníssono foi “All my loving”. Com imagens da época auge da Beatlemania projetadas no telão ao fundo do palco (havia também dois painéis laterais para aqueles que não estavam tão perto do palco), ele emendou outro clássico da banda mais popular que Jesus: “Drive My Car”. Sua atual banda também é “fantástica”, como disse para o público. Ela é formada por Paul Wix Wickens (teclado), Brain Ray (guitarra e baixo), Rusty Anderson (guitarra) e Abe Laboriel Jr. (bateria). Eles o ajudaram a homenagear os dois Beatles que já morreram: tocaram “Here Today”, a música que Paul escreveu para John Lennon (1940-1980), e dedicaram “Something” a George Harrison (1943-2001) - o quarto integrante do grupo, para quem não vive neste planeta, é o baterista Ringo Starr. -

Aki Tour Guide Book

Welcome to the Ozhaawashkwaa Animikii-Bineshi Aki Onji Kinimaagae’ Inun, the Blue Thunderbird Land-based Teachings Learning Center, or the Aki Center for short. Throughout the winter and spring of 2021, our grade 8 class has been investigating water and ecosystems health, access to clean water, and the role that water plays in our lives as humans. We’ve learned about how water is life for so many reasons. Another topic has been how prehistoric times and the rise of civilizations, have impacted where we are today. We were interested in how the land has changed so vastly over time, and here we are in the year 2021 making efforts to restore it as it could have been thousands of years ago. Through a variety of sources such as teachings from Elder Dan, Alex and Alexis at the Aki Center, and Waterlution (a national water organization), we’ve also become interested in how storytelling shapes how we relate to the land and each other. This is a tour of the Aki Center that looks at the special role each of the places here has on our prairie ecosystem. Our learning looks at where we’ve come from, and where we are going. There are 18 stops in total. We encourage you to spend time at each one, or visit a few every time you come! ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- You can few the tour using any of the following ways: - Bring this paper copy with you - Google Maps - Use a QR Code detector to hear us tell you about each special place ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1: Welcome to Seven Oaks School Division land-based teachings (by Jake) The Great Plains are a vast expanse of tallgrasses and fertile soil located in central Canada and Northern U.S.A. -

Für Sonntag, 21

InfoMail 21.12.15: PAUL McCARTNEY-MACCAZINES /// MANY YEARS AGO Weitere Info und/oder bestellen: Einfach Abbildung anklicken WhatsApp für MegaKurzInfo vom Beatles Museum und um zu bestellen; falls Du das nutzen möchtest, bitte eine WhatsApp senden: 01578-0866047 (Nummer nur für WhatsApp geschaltet.) Hallo M.B.M.! Hallo BEATLES-Fan! PAUL McCARTNEY-Paperback DOUBLE MACCAZINE Weitere Info und/oder bestellen: Einfach Abbildung anklicken Freitag, 6. Februar 2015: PAUL McCARTNEY: Paperback DOUBLE MACCAZINE - ALBUM SPECIAL - NEW - PART 1. 17,90 € Dutch Paul McCartney Fanclub, Niederlande. Heft; Hochformat A5: ca. 14,8 cm x ca. 21,0 cm; 68 Seiten; 4 Farb- und 115 Schwarzweiß-Abbildung; englischsprachig. Inhalt: Editoral. / Recording Something New … / January 2012: Meeting Paul Epworth, Ethan Johns and Mark Ronson. / Late Februar - June 1012: Continuing recording in the UK. / Between early and mid July 2012: New York City. / Mid September 2012: More sessions in New York City. / Early November 2012: More recordings with Ethan Johns. / December 2012: Approaching Giles Martin and more Mark Ronson. / January 2013: With Giles Martin at Hoog Hill Mills. / Februay - March 2013: With Giles Martin at Air Studios, London. / April 2013: Final mixes at Henson in Los Angeles. / July 2013: Abbey Road Studios. /July 2013: The end of the line. / Meet the NEW songs. / Interview quotes. / Meet the producer Giles Martin. / NEW - worldwide discography. Press release October 2013 - NEW credits - NEW cover artwork - NEW on cd's - NEW on vinyl - For promotional use only- NEW charts - NEW 2014 Japan tour edition - NEW 2014 collector's edition. Oktober 2015: PAUL McCARTNEY: Paperback DOUBLE MACCAZINE - ALBUM SPECIAL - NEW - PART 2 . -

Paul Mccartney O Cómo Sobrevivir a Lennon Y No Morir En El Intento.Pdf

Revista Arte Críticas participantes // enlaces // contacto sobre arte críticas Agenda Búsqueda tipo de búsqueda música artículos // críticas // debates // entrevistas // todos críticas octubre Paul McCartney o cómo sobrevivir a 2016 Lennon y no morir en el intento por Valeria Delgado Up and coming tour 2010, de Paul McCartney. Interpretado por Paul McCartney, guitarra, bajo, piano, teclados y voz;Paul ‘Wix’ Wickens, teclados; Brian Ray, guitarra, bajo; Rusty Anderson, guitarra y Abe Laboriel Jr., batería y coros. Estadio de River Plate, 10 de noviembre de 2010, 21 hs. Han pasado cuatro décadas, desde la disolución de The Beatles, y treinta años de la muerte de John Lennon, y su fantasma lo persigue. Sin embargo, aunque la sociedad Lennon- McCartney parece imposible de escindir, lenta y pacientemente Paul logró construir una carrera solista y erigirse como figura pública a la par del mito que dejó su ex co-equiper. En la rivalidad Lennon-McCartney, el último siempre llevó las de perder. John era rebelde, contestatario, transgresor, progre, genial. Paul, su contracara: formal, disciplinado, diplomático, vegetariano, familiero, conservador… genial. Y sí, McCartney también es genial. Es cierto que salir ISSN:1853-0427 de gira en familia y tener una esposa con cara de buena como Linda, no lo ha ayudado en los tiempos en que “sexo, droga y rock and roll” (que él también vivió intensamente) era el lema para que tanto público como colegas lo tomaran en serio. Por eso, Paul siempre dio la sensación de que tuvo que competir, como obligado a demostrar algo más. ¿Demostrar qué? ¿Acaso no alcanzaban las melodías extraordinarias de “Yesterday” o “Let it be”? No, porque en ningún momento se puso en duda sus capacidades artísticas o su talento musical, lo que lo hacía aparecer en inferioridad de condiciones era todo lo que lo rodeaba como figura pública. -

129,7M ($ 1.142’079.000), Barbitúricos

NACIÓ EN LIVERPOOL, INGLATERRA, EL 18 DE JUNIO DE 1942; INTEGRANTE DE THE QUARRYMEN (1957-1959), THE BEATLES (1960-1970) Y WINGS (1971-1981), AHORA TIENE 72 AÑOS Y NO PIENSA DETENERSE EN EL MUNDO MUSICAL Abril 28 Quito Ecuador Abril 25 Lima Out There!: Sir Paul McCartney se estaciona en Ecuador Perú Abril 19 Montevideo Disolución de Wings (1980) Colaboraciones (1982) 2013-2014: Out There! Tour Uruguay Inicio en The Beatles 1958/1963 Como intérprete y compositor McCartney es McCartney publica su segundo álbum en solitario, McCartney II, que Dos años después colaboró con Stevie Tras el éxito de su paso por América del Sur durante las giras alcanzó el primer puesto en la lista UK Albums Chart y el puesto 3 en Wonder en la canción Ebony and Ivory, Up and Coming Tour y On The Run Tour, la página ocial de Abril Club Jacaranda (1958) Pete Best Ringo Starr Brian Epstein responsable de 31 singles número uno en el Billboard la lista Billboard 200. Al igual que en su primer trabajo tras la incluida en el álbum Tug of War, y con McCartney conrmó un nuevo tour en la región: Out There. 22 y 23 Antes de que The Beatles se formase como Al nacer el Ya en Liverpool, Dueño de la disolución de The Beatles, McCartney compuso e interpretó las Michael Jackson en el tema The Girl is Mine, Con presentaciones en Montevideo (Uruguay), Santiago Santiago banda, John, Paul y George graban su primer nombre The arruinados, con tienda de discos canciones en solitario, sin músicos de sesión. -

International Festival 2008

International Festival 2008 southside sound Lateralus Consulting Inc. Transpath Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT MESSAGE FROM THE PRODUCER On behalf of the Cohenights Arts Society I welcome you to the Leonard Cohen Over the years I have had the good fortune to have produced a number of 2008 International Festival. Edmonton is honored to be the host of such a “theme” and “tribute” oriented projects. Paying homage to an artist’s body of prestigious event previously held in such famous cities as Montreal, New York, work is an endeavor that should be treated with the utmost of respect. and Berlin. That Leonard Cohen is the artist in question raises the stakes to another level It is a tremendous boom time in Edmonton, people flocking here from the rest as the man has created a body of work that has resonated across cultures and of Canada and all over the world to take part in our prosperity and enjoy the continues to have the kind of lasting impact reserved for precious few artists. jobs and opportunities here. We have a very vibrant cultural scene getting better day by day and we are very proud to be adding the Leonard Cohen Approaching artists who have been influenced by, and/or revere Cohen was International Festival to this mix. the first arrow to come out of the quiver when it came to putting the gala show for the International Leonard Cohen Festival together. We have spent three years preparing for this moment. It is very nice to see it all coming together at last. -

Volume 4 Issue 4 2011 Rock in Rio, Lisbon & Madrid - World’S Largest Music Festival

volume 4 issue 4 2011 Rock In Rio, Lisbon & Madrid - World’s Largest Music Festival. Sound by Gabisom Harman Professional sincerely thanks and appreciates the rental Sound Companies who use and support our audio products for concerts, festivals, tours and special events worldwide. www.harman.com © 2010 Harman. All rights reserved. THE POWER OFCHOICE _ ROCK IN RIO World’s Largest Music Festival Lisbon & Madrid JBL VT4889/ VT4880A System by: Gabisom FULLSIZE MODELS POWERED OPTION ACTIVE NETWORKED OPTIONS NOW AVAILABLE MIDSIZE MODELS WITH AES DIGITAL AUDIO & BSS OMNIDRIVE HD™ POWERED OPTION SIGNAL PROCESSING VERTEC® enables you to provide the inventory most likely to be requested for Tours, Events and Performance Venue projects COMPACT MODELS POWERED OPTION worldwide. With patents granted on JBL’s exclusive Differential Drive® technology and unique integral suspension hardware, the entire VERTEC product family is extremely portable and easy to set up. Powered models equipped Now Available with JBL DrivePack® technology are now available with F.I.R. filters NEW SUBCOMPACT MODELS and multi-stage limiting on the new DPDA input module, enabling users to more fully leverage the power of for digital remote control and monitoring. Powered or not, the choice is yours. Rediscover power at www.jblpro.com © 2010 JBL Professional con tenvolume 4 issuet 4 2011s 14 18 26 mobilePRODUCTIONmonthly 6 Sound Robe ROBIN 600 LEDWashes 24 Special FX SnowMasters Special Effects for Söhne Mannheim’s Tour Flogos-Lite Portable Series 8 Transportation Le Bas International 26 Rod Stewart From Behind the Secret Curtain Clean, Very Clean Home of the Superstar Coach 12 RN Entertainment: 30 Crew Members 31Tour Vendors 14 Peabo Bryson A Day with Peabo Bryson & Company Production Done the Hard Way 32 CT Touring Has Come a Long Way in a Short Time 18 Cavalia Part Two So You Say You Know What Touring Is Like Eh? 40 Advertiser's Index mobile production monthly 3 FROM THE Publisher In this issue we feature Rod Stewart and his Heart & Soul tour with gypsy-songstress Stevie Nicks. -

La, San Diego Arb's

WCFL CHANGES Radio PD5 COMPLETE NY, Records LA, SAN DIEGO THE INDUSTRY'S NEWSPAPER ARB'S VOL. 3, NUMBER 24 FRIDAY, JUNE 20. 1975 Bobby Poe Convention Highlights WCFL CHANGES PD's . As we reported last week, Ron O'Brien resigned from 99X -New York to take over the program director position of a major market rocker. This week the an- nouncement was completed when Lew Witz called R&R with the 6.4 details that Ron was coming to Mums Records GM Larry Douglas (right) presents Bill Tanner, ocrent Scott Shannor (right) accepts Medium Market PD of the year WCFL to be PD and hold down the 6 National PD tor Heftel, with Large Market PD of the year award f-_r his award from Capitol National Promotion to 10pm air shift. John Driscoll will successes at 'y100- Miami. Director Bruce Wendell. move to 10 pm to 2 am and become production director. CHICAGOARB OUT ..The major success story is in Country music for the "windy city." WMAQ NBC's new Country music outlet pulled way up to a 5.4 (Mon - Sunóam-12mid Av 1 -4 Hr Shares) from a 2.5 with their former MOR format. The new numbers pu them sixth in the market. In the rock battle WLS has 8.3, WCFL down further to a 4.6, WDHF up to a 2.7. The all news leader WBBM (CBS) is down over a share. WGN still dominant with a 14.5 overall. WVON (B) showed a slight increase as did WJPC (B). Most Contemporary stations were down in men 18 plus, while WGN, WIND and WMAO Atlantic Records was honored as Record Company of the Year, spawn are Consultant of the Year award went to Paul Drew, VP of Programming for picked up considerably.