Volume 13 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American ≤Uarter Horse Journal That You Can’T Get Anywhere Else Are the Breeding, Halter and Performance Statistics That We Mine from A≤HA’S Database

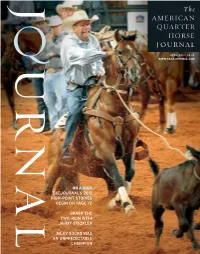

J J J J The AMERICAN ≤UARTER HORSE J OURNAL APRIL 2013 • $4.25 WWW.AQHAJOURNAL.COM U ≤≤U R R N N A A ON A HIGH THE JOURNAL’S 2012 HIGH-POINT STORIES BEGIN ON PAGE 72 GRASP THE TWO-REIN WITH L L JIMMY STICKLER SILKY SOCKS WAS AN UNPREDICTABLE CHAMPION CONTENTS FEATURES FEATURES 18 Structure in Detail 58 Hard To Get Playboy By Christine Hamilton By Jennifer K. Hancock The hind limb – looking at the stifle This Bank of America high-point senior horse has an all-around great personality 24 Borrow a Trainer By AQHA Professional Horseman 62 A≤HA’s 2012 Michael Colvin with Christine Hamilton High-Point Winners Lengthening stride at any gait 64 Making Runners 28 Barn Babies By Richard Chamberlain Breeders share their 2013 arrivals. Follow along with 2-year-olds on the track. Part of a continuing series 32 Grasping the Two-Rein By Annie Lambert 68 Ricky Ramirez Symbiosis of the mecate and bridle reins has By Honi Roberts enhanced training since the vaqueros developed This young jockey is going places – fast. it into an art form. 38 The Unpredictable 78 Foundation Donors Champion By Larri Jo Starkey April 2013 Silky Socks spooked on a dime, but he The official publication had a world championship ride in him. of the American Quarter 44 60 Years Ago These two are Horse Association. AQHA’s first high-point award winners all-around About the Cover 46 characters. 2012 AQHA All-Around 46 Kaleena Weakly and Senior Horse Hard To Get Playboy Hours Yours And Mine By Jennifer K. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

On the Laws and Practice of Horse Racing

^^^g£SS/^^ GIFT OF FAIRMAN ROGERS. University of Pennsylvania Annenherg Rare Book and Manuscript Library ROUS ON RACING. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/onlawspracticeOOrous ON THE LAWS AND PRACTICE HORSE RACING, ETC. ETC. THE HON^T^^^ ADMIRAL ROUS. LONDON: A. H. BAILY & Co., EOYAL EXCHANGE BUILDINGS, COENHILL. 1866. LONDON : PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET, AND CHAKING CROSS. CONTENTS. Preface xi CHAPTER I. On the State of the English Turf in 1865 , . 1 CHAPTER II. On the State of the La^^ . 9 CHAPTER III. On the Rules of Racing 17 CHAPTER IV. On Starting—Riding Races—Jockeys .... 24 CHAPTER V. On the Rules of Betting 30 CHAPTER VI. On the Sale and Purchase of Horses .... 44 On the Office and Legal Responsibility of Stewards . 49 Clerk of the Course 54 Judge 56 Starter 57 On the Management of a Stud 59 vi Contents. KACma CASES. PAGE Horses of a Minor Age qualified to enter for Plates and Stakes 65 Jockey changed in a Race ...... 65 Both Jockeys falling abreast Winning Post . 66 A Horse arriving too late for the First Heat allowed to qualify 67 Both Horses thrown—Illegal Judgment ... 67 Distinction between Plate and Sweepstakes ... 68 Difference between Nomination of a Half-bred and Thorough-bred 69 Whether a Horse winning a Sweepstakes, 23 gs. each, three subscribers, could run for a Plate for Horses which never won 50^. ..... 70 Distance measured after a Race found short . 70 Whether a Compromise was forfeited by the Horse omitting to walk over 71 Whether the Winner distancing the Field is entitled to Second Money 71 A Horse objected to as a Maiden for receiving Second Money 72 Rassela's Case—Wrong Decision ... -

Morgan Horses

The 12th Annual NATIONAL MORGAN HORSE SHOW Sponsored by: Saturday Evening Friday Evening 7:00 P. M. 7:00 P. M. Sunday Saturday Afternoon Afternoon 1:00 P. M. 1:00 P. M. PERFORMANCE BREED CLASSES CLASSES For Stallions and Saddle, Harness, Mares: Colts and Pleasure. Utility Fillies and Equitation THE MORGAN HORSE CLUB Watch The Foundation Breed of America Perform. TRI-COUNTY FAIR GROUNDS NORTHAMPTON, MASS. July 30, 31 and August 1, 1954 Adults $1.00 Children - under 12 - 50' A LAW FOR IT . by 1939 Vermont Legislature "There oughta be a law agin it," is a favorite expresion of Vermonters. Sometimes they reverse themselves and make a law "for it" as they did in 1939 when the legislature passed the following resolution: "Whereas, this is the year recognized as the 150th anniversa y of the famous horse 'Justin Morgan,' which horse not only established a recognized breed of horses named for a single individual, but brought fame th•tzugh his descendants to Vermont and thousands of dollars to Vermonters. "The name Morgan has come to mean beauty, spirit, and action to all lovers of the horse; and the Morgan horses fo• many years held the world's record for trotting horses, and "Whereas the Morgan blood is recognized as foundation stock for the American Saddle Horse, for the American Trotting Horse, and for the Tennessee Walking Horse. In each of these three breeds, the Morgan horse is recognized as a foundation, and therefore, with the recognition of its value to the horse b seeders of the nation, and recognition that it was in Vermont that Morgan -

Fttdec2008cat.Pdf

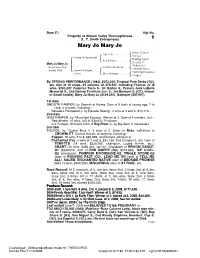

Barn E1 Hip No. Property of Hidden Valley Thoroughbreds (L. T. Smith Enterprises) 1 Mary Jo Mary Jo Native Dancer Jig Time . { Kanace Strong Performance . Blazing Count { Extra Alarm . { Deedee O. Mary Jo Mary Jo . *Noholme II Gray/roan mare; Smooth At Holme . { *Smooth Water foaled 1993 {Smooth Pamper . *Moonlight Express (1981) { Miss Pamper . { Poupee By STRONG PERFORMANCE (1983), $252,040, Tropical Park Derby [G2], etc. Sire of 15 crops, 35 winners, $1,375,507, including Thomas Jo (8 wins, $390,207, Federico Tesio S., Sir Barton S., Francis Jock LaBelle Memorial S., 2nd Gallery Furniture Juv. S., 3rd Belmont S. [G1]; winner in Saudi Arabia), Mary Jo Mary Jo ($169,240), Quitaque ($97,907). 1st dam SMOOTH PAMPER, by Smooth at Holme. Dam of 9 foals of racing age, 7 to race, 4 winners, including-- Nevada’s Pampered (f. by Nevada Reality). 3 wins at 3 and 4, $10,713. 2nd dam MISS PAMPER, by *Moonlight Express. Winner at 3. Dam of 4 winners, incl.-- Redskinette. 10 wins, 3 to 6, $30,052. Producer. Jr’s Pamper. Unraced. Dam of Big River (c. by Big Gun) in Venezuela. 3rd dam POUPEE, by *Quatre Bras II. 3 wins at 2. Sister to Bras, half-sister to CROWNLET. Dam of 9 foals, all winners, including-- Puppet. 18 wins, 2 to 8, $56,895, 3rd Richard Johnson S. Enchanted Eve. 4 wins at 2 and 3, $32,230, 2nd Comely H., etc. Dam of TEMPTED (18 wins, $330,760, champion, Ladies H.-nAr, etc.), SMART (19 wins, $365,244, set ntr). Granddam of BROOM DANCE- G1 ($330,022, dam of END SWEEP [G3], $372,563), ICE COOL- G2 (champion), PUMPKIN MOONSHINE-G2; TINGLE STONE-G3 (dam of ROUSING PAST [G3]), LEAD ME ON (dam of TELL ME ALL), SALEM, ENCHANTED NATIVE (dam of BEDSIDE PROMISE [G1] 14 wins, $950,205), MISGIVINGS (dam of AT RISK), etc. -

Horse-Breeding in England and India : and Army Horses Abroad

IK#^^"^'^ 'ND iNDIA AN! \BR( LIBRARY OF LEONARD PEARSON VETERINARIAN : SECOND EDITION Horse-Breeding I N England and India AND Army Horses Abroad BY SIR WALTER GILBEY, BART. Author of Horses for the Army , The Great or War Horse ; Small Horses IN Warfare; Horses Past and Present; The Harness Horse; Young Race-Horses ; Early Carriages and Roads ; Animal Painters OF England, &c., &c. ILLUSTRATED LONDON Vinton & Co., 9 New Bridge Street, E.C. 1906 G313 \JNtV£R6IVY 1 iSYLVe.,: . -+- CONTENTS , ^: Horse-Brkeding IX i8('>4 The Present State of Affairs Horses Bred in England Horses Bred for Sport Only 4 6 Purchase of English Mares by Foreigners . Horses AVanteu for the Army 7 Sizeable Harness Horses 9 Private Enterprise in England II Breeding Without Prejudice 12 Landlords would do well to give Choice of Stallions 13 Cause of Failure in English Horse-Breeding 13 Height of Race-Horses from 1700 to 1900 14 Character of Race-Horses from 1700 to 1900 16 iS The Introduction of Short Races . The Roadster of a Century Ago 19 What Foreign Nations are Doing 20 Horse-Breeding in France 22 Horse-Breeding'in Germany (Pruss(a) 30 Horse-Breeding in Hungary 35 Hokse-Breeding in Austria 39 Horse-Breeding in Italy 42 Horse-Breeding in Russia 44 Horse-Breeding in Turkey 49 Horse-Breeding in India : Opinions of the Late Veterinary-Colonel Hallen — First endeavours to improve Native Breeds. Army Remounts and Horse-Breeding. Native Mares. Difficulties in the way of improvement. Purchase of stallions. English Thoroughbreds. Objections to Thoroughbred Stallions. Thoroughbreds from Australia. -

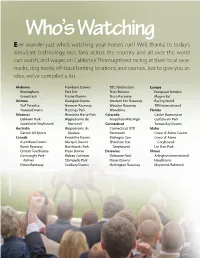

Ever Wonder Just Who's Watching Your Horses Run? Well, Thanks to Today's

Who’s Watching Ever wonder just who’s watching your horses run? Well, thanks to today’s simulcast technology, race fans across the country and all over the world can watch, and wager, on California Thoroughbred racing at their local race- tracks, dog tracks, off-track betting locations, and casinos. Just to give you an idea, we’ve compiled a list… Alabama Flamboro Downs TBC Teletheaters Europe Birmingham Fort Erie Trois-Rivieres European Simulco Greentrack Frasier Downs Truro Raceway Magna Bet Arizona Georgian Downs Western Fair Raceway Racing World Turf Paradise Hanover Raceway Windsor Raceway TRN International Yavapai Downs Hastings Park Woodbine Florida Arkansas Hiawatha Horse Park Colorado Calder Racecourse Oaklawn Park Hippodrome de Arapahoe-Mile High Gulfstream Park Southland Greyhound Montreal Connecticut Tampa Bay Downs Australia Hippodrome de Connecticut OTB Idaho Darwin All Sports Quebec Foxwoods Coeur d’ Alene Casino Canada Kawartha Downs Mohegun Sun Coeur d’ Alene Assiniboia Downs Marquis Downs Shoreline Star Greyhound Barrie Raceway Northlands Park Greyhound Les Bois Park Clinton Teletheatre Picov Downs Delaware Illinois Connaught Park- Rideau Carleton Delaware Park Arlington International Aylmer Stampede Park Dover Downs Hawthorne Elmira Raceway Sudbury Downs Harrington Raceway Maywood/Balmoral wners' 8 O'Circle 9 Turfway Park Nebraska Divi Carina Bay Casino Rhode Island Indiana Atokad Elite Turf Club Lincoln Greyhound Evansville OTB Fonner Park Equus St. Thomas Newport Jai Alai Hoosier Park Horseman’s Park Racing South -

2019 Conference Program

2019 Conference Program The Where the Past and the Present Become Lessons for the Future 73rd Annual Conference Sunday, May 19 — Wednesday, May 22, 2019 MacArthur USS Wisconsin Chrysler Museum Memorial Museum of Art International Institute of Municipal Clerks Professional, Personal Code of Ethics Believing in freedom throughout the World, allowing increased cooperation between public officials, and others, nationally and internationally, I MEMBERS NAME & TITLE EMPLOYER do hereby subscribe to the following principles and ethics which I affirm will govern my personal conduct as a member of IIMC: To uphold constitutional government and the laws of my community; To so conduct my public and private life as to be an example to my fellow citizens; To impart to my profession those standards of quality and integrity that the conduct of the affairs of my office shall be above reproach and to merit public confidence in our community; To be ever mindful of my neutrality and impartiality, rendering equal service to all and to extend the same treatment I wish to receive myself; To record that which is true and preserve that which is entrusted to me as if it were my own; and To strive constantly to improve the administration of the affairs of my office consistent with applicable laws and through sound management practices to produce continued progress and so fulfill my responsibilities to my community and others. These things I, as a member of IIMC, do pledge to do in the interest and purposes for which our government has been established. ___________________________________________ (member signature) This certificate granted by the authority of the International Institute of Municipal Clerks. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name,Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 7 Consigned by Ashview Farm LLC (Mr. and Mrs. Wayne G. Lyster III), Agent Broodmare 1780 b. m. Hurricane Victress, 1997 Sharp Victor Woody's Miss Broodmare prospect 1840 dk. b./br. m. Military Victress, 2002 Military Hurricane Victress Barn 9 Consigned by Blandford Stud (Padraig Campion), Agent Broodmare 1693 ch. m. Dance Trick, 1995 Diesis (GB) Performing Arts (IRE) Racing or broodmare prospect 1846 b. m. Missisipi Star (IRE), 2003 Mujahid Kicka Racing or stallion prospect 1874 b. c. Wafi City, 2004 E Dubai My Jody Racing prospect 1611 dk. b./br. f. unnamed, 2006 Roaring Fever Waywayanda Barn 2 Consigned by Bluewater Sales LLC, Agent I Yearling 1631 b. f. unnamed, 2007 Chapel Royal Alma Mater Barn 2 Consigned by Bluewater Sales LLC, Agent III Broodmare 1850 ch. m. Miss Phone Chatter, 2000 Phone Trick Passing My Way Broodmare prospect 1732 ch. m. Fancy Forever, 2003 Wild Rush Opinionated Lady Barn 2 Consigned by Bluewater Sales LLC, Agent IV Broodmare prospect 1678 dk. b./br. f. Classy Clarita, 2004 Mr. Greeley Link to Erin Barn 2 Consigned by Bluewater Sales LLC, Agent V Yearlings 1589 dk. b./br. c. unnamed, 2007 Offlee Wild Theatriken 1610 b. c. unnamed, 2007 Maria's Mon Way Beyond Barn 2 Consigned by Bluewater Sales LLC, Agent VI Racing or broodmare prospect 1694 gr/ro. f. Dancing Cherokee, 2004 Yonaguska Dancapade Barn 2 Consigned by Bluewater Sales LLC, Agent VII Yearling 1787 dk. b./br. f. unnamed, 2007 Offlee Wild Jettin Diplomacy Barn 2 Consigned by Bluewater Sales LLC, Agent VIII Broodmare 1754 b. -

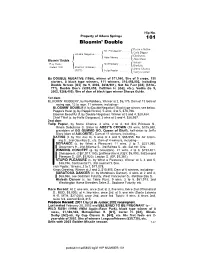

Page 1 by DOUBLE NEGATIVE (1986), Winner of $71,560. Sire of 5

Hip No. Property of Adena Springs 101 Bloomin’ Double Raise a Native Mr. Prospector . { Gold Digger Double Negative . Distinctive { Able Money . { Able Maid Bloomin’ Double . Swaps Bay mare; No Robbery . { Bimlette foaled 1994 {Bloomin’ Robbery . Some Chance (1975) { Tulip Poplar . { Glory’s Crown By DOUBLE NEGATIVE (1986), winner of $71,560. Sire of 5 crops, 130 starters, 8 black type winners, 111 winners, $10,456,002, including Double Screen [G3] (to 9, 2002, $638,901), Not So Fast [G3] ($318,- 777), Double Dee’s ($293,052, Cotillion H. [G2], etc.), Vodka (to 5, 2002, $286,405). Sire of dam of black type winner Sherpa Guide. 1st dam BLOOMIN’ ROBBERY, by No Robbery. Winner at 2, $6,175. Dam of 13 foals of racing age, 12 to race, 11 winners, including-- BLOOMIN’ DOUBLE (f. by Double Negative). Black type winner, see below. Pappa’s Heist (g. by Pappa Riccio). 5 wins, 3 to 5, $78,796. Bloomin Beautiful (f. by Double Negative). Winner at 3 and 4, $29,484. Chief Thief (c. by Hello Gorgeous). 3 wins at 3 and 4, $26,957. 2nd dam Tulip Poplar, by Some Chance. 4 wins, 2 to 4, 3rd Illini Princess S., Illinois Debutante S. Sister to ABBY’S CROWN (19 wins, $105,590, granddam of GO GUMMO GO, Queen of Bluff), half-sister to Jeff’s Glory (dam of AGLORITE). Dam of 11 winners, including-- DATING (f. by The Axe II). 6 wins at 4 and 5, $66,955, Bel Air Claim- ing S., 2nd Osunitas S., etc. Dam of 4 winners, including-- DEFIANCE (c. -

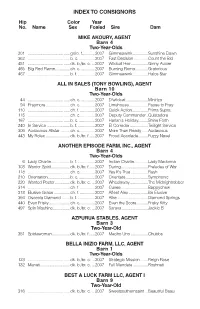

TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam MIKE AKOURY, AGENT Barn 4 Two-Year-Olds 201 ................................. ......gr/ro. f............2007 Gimmeawink ..............Sunshine Dawn 362 ................................. ......b. c................2007 Fast Decision .............Count the Bid 451 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2007 Wildcat Heir................Ginny Auxier 465 Big Red Flame..............ch. c. .............2007 Burning Roma............Gratorious 467 ................................. ......b. f. ................2007 Gimmeawink ..............Halos Star ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn 10 Two-Year-Olds 44 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2007 D'wildcat.....................Miniriza 94 Praymore.......................ch. c. .............2007 Limehouse..................Pause to Pray 110 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2007 Quick Action...............Prima Supra 115 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2007 Deputy Commander..Quistadora 167 ................................. ......b. c................2007 Harlan's Holiday.........Shine Forth 240 In Service ......................b. f. ................2007 El Corredor.................Twilight Service 306 Audacious Allstar .........ch. c. .............2007 More Than Ready......Audacious 443 My Rolex .......................dk. b./br. f......2007 Proud Accolade.........Fuzzy Navel ANOTHER EPISODE FARM, INC., AGENT Barn 4 Two-Year-Olds 6 Lady Charlie..................b. -

Description of the Birmingham Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE BIRMINGHAM QUADRANGLE. By Charles Butts. INTRODUCTION. that flow across it toward the Atlantic. The Appalachian Tennessee, in Sequatchie Valley, and along Big Wills Creek Mountains occupy a broad belt extending from southwestern are parts of the same peneplain. Below the Coosa peneplain LOCATION, EXTENT, AND GENERAL RELATIONS. Virginia through western North Carolina and eastern Ten the streams of the southern part of the Appalachian province As shown by the key map (fig. 1), the Birmingham quad nessee to northeastern Georgia. This belt is a region of strong have eroded their present channels. rangle lies in the north-central part of Alabama. It is bounded relief, characterized by points and ridges 3000 to 6000 feet or Drainage. The northern part of the Appalachian province by parallels 33° 30' and 34° and meridians 86° 30' and 87° over in height, separated by narrow V-shaped valleys. The is drained through St. Lawrence, Hudson, Delaware, Susque- and contains, therefore, one-quarter of a square degree. Its general level of the Appalachian Valley is much lower than hanna, Potomac, and James rivers into the Atlantic and length from north to south is 34.46 miles, its width from east that of the Appalachian Mountains on the east and of the through Ohio River into the Gulf of Mexico; the southern Appalachian Plateau on the west. Its surface is character part is drained by New, Cumberland, Tennessee, Coosa, and 87 ized by a few main valleys, such as the Cumberland Valley in Black Warrior rivers into the Gulf. In the northern part £35 Pennsylvania, the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, the East many of the rivers rise on the west side of the Great Appa Tennessee Valley in Tennessee, and -the Coosa Valley in lachian Valley and flow eastward or southeastward to the Alabama, and by many subordinate narrow longitudinal val Atlantic; in the southern part the direction of drainage is leys separated by long, narrow ridges rising in places 1000 to reversed, the rivers rising in the Blue Ridge and flowing west 1500 feet above the general valley level.