Finding Common Ground: Coordinating Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Issues Facing Somali Refugees in Minneapolis, MN MPP

Housing Issues Facing Somali Refugees in Minneapolis, MN MPP Professional Paper In Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Public Policy Degree Requirements The Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs The University of Minnesota Jeffrey D. Dischinger December 15, 2009 _____________________________ __________ Assistant Professor Ryan Allen Date Signature of Paper Supervisor, certifying successful completion of oral presentation _____________________________ __________ Assistant Professor Ryan Allen Date Signature of Paper Supervisor, certifying successful completion of professional paper _____________________________ __________ Professor Edward G. Goetz Date Signature of Second Committee Member, certifying successful completion of professional paper Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature Review 3 3. Background and Demographics of Somalis in Minneapolis 7 4. Provider Interviews 18 5. Community Organizations 23 6. Recommendations 26 1. Introduction Somali immigrants face many obstacles when finding housing that suits their needs and more can be done to improve their housing conditions and options. Minnesota is home to the largest Somali population in the United States and most of them live in the Minneapolis area. As a matter of fact, more than half of the Somalis coming to the United States settle in Minnesota with the majority of these living in the Twin Cities. Of these immigrants, many are refugees that came from horrific conditions living in refugee camps due to an unstable central government in Somalia. Since 1991, Somalia has been split into four separate areas and political persecution a constant fear of many Somalis. Many Somalis have died due to the ongoing conflict between political beliefs and many survivors have fled to refugee camps where they live in poor conditions waiting and hoping that the government will eventually stabilize. -

What Affordable Housing Programs and Initiatives

WHAT AFFORDABLE HOUSING PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES DOES THE DISTRICT OFFER? DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT: • Inclusionary Zoning Affordable Housing Program (IZ) sets aside a percentage of affordable rental or for-sale units in new residential development projects of 10 or more units as well as rehabilitation projects that are expanding an existing building by 50 percent or more. Households interested in purchasing or leasing an IZ home must take the IZ orientation class with one of DHCD partner community-based organizations and complete the online registration form. For more information, please visit the following link: www.dhcd.dc.gov/service/inclusionary-zoning-affordable-housing-program • The Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) is a special revenue fund administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development. The HPTF provides funding for the production and preservation of homes that are affordable to low-income households in the District in a wide variety of ways. The primary use of the fund is as “gap financing” that enables housing projects to have sufficient financing to provide affordable housing. The fund also provides other forms of assistance including: - pre-development loans to assist nonprofit housing developers in getting low income housing projects funded; - financing for site acquisition to provide locations to build affordable housing; - funding for the rehabilitation of single family homes. Since 2001, the HPTF has helped produce over 9,000 affordable homes for low income District residents. For more information, please visit the following link: https://dhcd.dc.gov/page/housing-production-trust-fund • The Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) provides interest-free loans and closing cost assistance to qualified applicants to purchase single-family houses, condominiums, or cooperative units. -

Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority (FCRHA) and Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD)

Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority (FCRHA) and Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) Strategic Plan for FY 2021 Adopted March 5, 2020 http://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/housing/data/strategic-plan A publication of Fairfax County Fairfax County is committed to a policy of nondiscrimination in all County programs, services and activities and will provide reasonable accommodations upon request. Please call 703.246.5101 or TTY 711. Who’s Who Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority Commissioners (As of February 2020) Robert H. Schwaninger (Mason District), Chairman C. Melissa Jonas (Dranesville District), Vice-Chairman Matthew Bell (Mount Vernon District) Christopher Craig (Braddock District) Kenneth G. Feng (Springfield District) Lenore Kelly (Sully District) Richard Kennedy (Hunter Mill District) Albert J. McAloon (Lee District) Ezra Rosser (At-Large) Rod Solomon (Providence District) Sharisse Yerby (At-Large) Department of Housing and Community Development Thomas Fleetwood, Director Amy Ginger, Deputy Director, Operations Teresa Lepe, Deputy Director, Real Estate, Finance and Development * * * * * Seema Ajrawat, Director, Financial Management and Peggy Gregory, Director, Rental Assistance Information Systems and Services Margaret Johnson, Director, Rental Housing Judith Cabelli, Director, Affordable Housing Development Ahmed Rayyan, Director, Design, Development and Construction Marta Cruz, Director of Administration Vincent Rogers, Director, Policy and Compliance Carol Erhard, Director, Homeownership/Relocation -

~'Fhetattzl£Il'

JANUARY 2017 ~'fHETATTZl£Il' . ~ .. , . ' JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY GUILD OF DALY CITY ..COLMA I GREETINGS FROM PRESIDENT MARK For our fIrst meeting ofthe new year, we welcome back DAYTIME longtime Guilder and old friend Neil Fahy, who will discuss the geology of Daly City and the surrounding area. Neil is a HISTORY MEETING retired geologist by profession and authority on the various SUNDAY, JANUARY 15TH, 2 PM strata that makeup Daly City. He will share his knowledge of 101 Lake Merced Blvd. Daly City, Doelger Center Cafe the area and explain about past earthquakes that have had an impact in the area going back thousands of years to the more recent ones that many of us remember all too well. Come LIVING ON THE EDGE prepared with any questions you might have except, of course, An Introduction to the Geology of Daly City for exactly when the 'big one' might hit as nobody knows for certain. If you haven't already had a chance to return your 2017 dues, we certainly hope that you will shortly. It is your support, and only your support, that allows us to pay the bills and keep the Guild running. Operating a museum is not cheap, and we always do the best that we can on a shoestring budget. Perhaps you might like to consider renewing your membership at a different level of support. We have various categories to recognize your generosity, and at the end ofthe day it all goes toward sustaining the Guild. Whatever level of support is right for you we certainly appreciate your membership and regard for all that we do to preserve local history. -

Emergency Housing & Services Quick Referral List

EMERGENCY HOUSING & SERVICES QUICK REFERRAL LIST 2014-2015 Delaware Affordable Housing Services Directory If you have no financial resources and are in need of immediate help for emergency housing or housing-related services, the following agencies may be able to assist you. Delaware Helpline 1-800-464-4357 For Most Emergencies: Delaware State Service Centers This Directory, Page 13 Emergency Shelters & This Directory Pages 80 - 91 Transitional Housing Delaware State Service Centers This Directory, Page 13 Emergency Home Heating Fuel Wilmington: (302) 654-9295 Catholic Charities Dover: (302) 674-1782 Assistance Georgetown: (302) 856-6310 Emergency Home Dover, City of (302) 736-7175 Weatherization, Repairs New Castle: (302) 498-0454 First State Community Action Agency Dover: (302) 674-1355 Georgetown: (302) 856-7761 Inter-Neighborhood Foundation (302) 429-0333 Wilmington Kent County Levy Court, (302) 744-2480 Department of Planning Services Lutheran Community Services (302) 654-8886 (N.C.C., Elderly and Disabled only) Neighborhood House, Wilmington (302) 652-3928 Newark Senior Center (302) 737-2336 New Castle County Department of (302) 395-5618 Community Services (Seniors) Catholic Charities - Basic Needs Emergency Financial Assistance Wilmington (302) 654-9295 (Security Deposit, Mortgage Payment, Dover (302) 674-1600 Small Funds) Georgetown (302) 856-9578 F.A.I.T.H. Center, Inc. (N.C.C.) (302) 654-4550 Emergency Foreclosure Assistance: Lutheran Community Services (N.C.C.) (302) 654-8886 www.DelawareHomeownerRelief.com (Qualifying Individuals) Salvation Army - Wilmington (302) 472-0700 Housing Counselors, Page 18 Dover (302) 678-9551 Seaford (302) 628-2020 Attorney General’s Foreclosure West End Neighborhood House Hotline: 800-220-5424 (302) 658-4171 (Statewide) Security Deposit Loan Program Dept. -

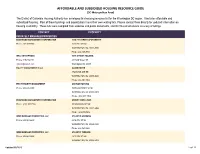

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

Housing Allocation, Homelessness and Stock Transfer a Guide to Key Issues

Housing Allocation, Homelessness and Stock Transfer A Guide to Key Issues January 2004 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister: London Office of the Deputy Prime Minister Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone 020 7944 4400 Web site www.odpm.gov.uk Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Further copies of this publication are available from: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister Publications PO Box 236 Wetherby LS23 7NB Tel: 0870 1226 236 Fax: 0870 1226 237 Textphone: 0870 1207 405 Email: [email protected] or online via the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister’s web site. Printed in Great Britain on material containing 75% post-consumer waste and 25% ECF pulp. January 2004 Product code: 03HC01808 Acknowledgements We would like to express our thanks to Hal Pawson of Heriot-Watt University and to David Mullins and Rob Rowlands of Birmingham University for producing the research findings on which this Guide is based. We are also extremely grateful to the case study interviewees who participated in the research from both housing authorities and housing associations for providing examples and agreeing to their use in this Guidance. We also acknowledge assistance from Michele Walsh, Housing Corporation and Gill Green and Roger Jarman, Audit Commission, as well as to internal policy colleagues in ODPM, in providing access to further good practice examples and commenting on earlier drafts of the Guide. -

Breaking Common Ground

SUSTAINABILITY CASE OF THE FUTURE STUDIES Breaking common ground Are the days of the ‘glass box’ office or residential block numbered? An integrated social housing project broke new ground NDY’s Chris Nunn believes that in sustainability and philanthropy. while these buildings meet the aesthetic desire for natural light FIONA BAKER and great views, they struggle to weather the high solar loads and demands for cooling. These glass boxes in their current design will be far from ideal for the future. “The remedy is an increased focus on high-performance facade and fabric, in particular PROJECT: Camperdown Common Ground airtightness, better construction PROJECT CLIENT: Mission Australia and the NSW Department of Housing detailing to reduce uncontrolled SCOPE: Construction of a six-storey complex that provides innovative inner-city accommodation leaks and heat gains, and earlier for Sydney’s homeless and low income earners use of energy modelling as part COMPLETION: November 2011 of a more integrated, iterative design process,” Nunn says. He cites building trends in Europe as leading the way in energy-efficient construction. “Architects and engineers are working together to create BACKGROUND BRIEFING aesthetically striking facades KEY CHALLENGE KEY PLAYERS Providing safe shelter and housing for that respond appropriately to the estimated 105,000 homeless people Since its completion, Common Process the solar context of the site.” in Australia is always a high priority for Ground Sydney has achieved hydronic heating panels, which have weather welfare groups like Mission Australia. the much-lauded 5 Star Green The team identified two major areas that would compensation controls to ensure heating is not Some of the innovations include: In a city like Sydney where large numbers Building Council of Australia ensure success: achieving the sustainability and left on when not needed. -

PDF Download Little Boxes Ebook, Epub

LITTLE BOXES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Caroline Casey | 208 pages | 29 Aug 2017 | Coffee House Press | 9781566894722 | English | MN, United States Little Boxes PDF Book Little boxes on the hillside, Little boxes made of ticky tacky Little boxes on the hillside, Little boxes all the same, There's a pink one and a green one And a blue one and a yellow one And they're all made out of ticky tacky And they all look just the same. Be Kind To Your Parents. Provide song facts, names, places and other worthy info that may give readers a perfect insight on the song's meaning. Does it mean anything special hidden between the lines to you? Edit page. Go and do it people, don't let money run your life, its all a big con to keep the people dumbed down. Movie Player. Ask us or our community about the part of the song that interests you We will try to respond as soon as possible. Yvette Nailor. New York: Norton. Julie Hays. In the second and third seasons, different artists performed Little Boxes in the introduction sequence of each episode. We just try to fit in and by the process lose our uniqueness and come out looking just like everybody else. We become made of ticky tacky and we will raise our children the same. Post my meaning Write my explanation new To explain lyrics, select line or word and click "Explain". Awards 5 nominations. View 10 more explanations. Make sure you've read our simple tips Hey! Make sure you've read our simple tips Hey! Mack : Come on Clark, you can tell me. -

Elizabeth Street Common Ground 5Th Anniversary

Elizabeth Street Common Ground 5th Anniversary “ I’ve been five years now… very dubious at the start. At the moment, I’ve got so much positivity in me. I’m achieving things I couldn’t even dream about before.” — Tex, tenant Introduction Five years ago, Elizabeth Street Common Ground opened its doors and became home to 65 Melburnians in desperate need of housing and support. The 11-storey residential building and untreated health issues, police was the first of its kind to be purpose- intervention and incarceration. For most, built in Melbourne, designed to house life was about day-to-day survival. Their and support the most vulnerable and lives were often characterised by chaos, disadvantaged people in our community. addiction, eviction, uncertainty, family violence, abuse, isolation and despair. It marked the culmination of more than three years of planning, development, Most have embraced the opportunity fundraising and building by HomeGround to get their lives on track, and while Services (now Launch Housing), Yarra some have had to leave, many stay on Community Housing, the Victorian and and continue to contribute to their new Federal Governments, construction community. company Grocon and a committed group We’d like to thank our staff, supporters, of private companies, philanthropists and tenants and all those who have made community service organisations. Elizabeth Street Common Ground a It is almost impossible to overstate the reality. importance of the first five years of this It’s been challenging for us all, but we’ve ambitious supportive housing project: learned important lessons about the lives have been saved, and changed for Common Ground supportive housing the better. -

EWISH Vo1ce HERALD

- ,- The 1EWISH Vo1CE HERALD /'f) ,~X{b1)1 {\ ~ SERVING RHODE ISLAND AND SOUTHEASTERN MASSACHUSETTS V C> :,I 18 Nisan 5773 March 29, 2013 Obama gains political capital President asserts that political leaders require a push BY RON KAMPEAS The question now is whether Obama has the means or the WASHINGTON (JTA) - For will to push the Palestinians a trip that U.S. officials had and Israelis back to the nego cautioned was not about get tiating table. ting "deliverables," President U.S. Secretary of State John Obama's apparent success Kerry, who stayed behind during his Middle East trip to follow up with Israeli at getting Israel and Turkey Prime Minister Benjamin to reconcile has raised some Netanyahu's team on what hopes for a breakthrough on happens next, made clear another front: Israeli-Pales tinian negotiations. GAINING I 32 Survivors' testimony Rick Recht 'rocks' in concert. New technology captures memories BY EDMON J. RODMAN In the offices of the Univer Rock star Rick Recht to perform sity of Southern California's LOS ANGELES (JTA) - In a Institute for Creative Technol dark glass building here, Ho ogies, Gutter - who, as a teen in free concert locaust survivor Pinchas Gut ager - had survived Majdanek, ter shows that his memory is Alliance hosts a Jewish rock star'for audiences ofall ages the German Nazi concentra cr ystal clear and his voice is tion camp on the outskirts of BY KARA MARZIALI Recht, who has been compared to James Taylor strong. His responses seem a Lublin, Poland, sounds and [email protected] for his soulfulness and folksy flavor and Bono for bit delayed - not that different looks very much alive. -

2C Minutes CD.Pdf

SUMMARY INDEX FOR PUBLIC WORKS/CIP & LAND USE COMMITTEE April 24, 2017 ITEM ACTION PAGE 1. Call to Order Convened at 5:00 p.m. 1 2. RollCall Quorum Present 1 3. Approval of Agenda Approved as amended 1-2 4. Approval of Consent Agenda Approved as amended 2 5. Approval of Minutes- April10, 2017 Approved as presented 2 CONSENT AGENDA LISTING Listed 2-3 6. Traffic Signal Cabinets 9. DeFouri/Guadalupe Bridge Improvements 10. Fort Marcy/Majors Field Bridge Replacement CONSENT AGENDA DISCUSSION 7. School Flasher Connect System Approved 3-4 PUBLIC HEARING 11. Accessory Dwelling Unit Ordinance Amendment Discussion 4-14 12. Matters from Staff None 14 13. Matters from the Committee None 14 14. Matters from the Chair Comments 14 15. Next Meeting: May 8, 2017 14 16. Adjournment Adjourned at 7:26 p.m. 14-15 Public Works/CIP &Land Use Committee April24, 2017 PageD MINUTES OF THE CITY OF SANTA FE PUBLIC WORKS/CIP & LAND USE COMMITTEE Monday, April24, 2017 1. CALL TO ORDER A regular meeting of the Public Works/CIP & Land Use Committee was called to order on the above date by Councilor Peter N. lves, Chair at approximately 5:00p.m. in City Council Chambers, City Hall, 200 Lincoln Avenue, Santa Fe, New Mexico. 2. ROLLCALL Roll Call indicated the presence of a quorum as follows: MEMBERS PRESENT: Councilor Peter N. lves, Chair Councilor Christopher M. Rivera Councilor Renee D. Villarreal MEMBERS EXCUSED: Councilor Joseph M. Maestas Councilor Ronald S. Trujillo STAFF PRESENT: John Romero, Acting Public Works Director Bobbi Huseman, Public Works Staff OTHERS PRESENT: Carl Boaz, Stenographer NOTE: All items in the Committee packet for all agenda items were incorporated herewith by reference.