A New Pollen Sequence from Southern Iberia Suggesting Coastal Pleistocene Phytodiversity Hotspot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Actinorhizal Plants of Kumaun Himalaya and Their Ecological

International Scholars Journals Advances in Agriculture and Agricultural Sciences ISSN 2381-3911 Vol. 6 (7), pp. 001-006, July, 2020. Available online at www.internationalscholarsjournals.org © International Scholars Journals Author(s) retain the copyright of this article. Full Length Research Paper Actinorhizal plants of Kumaun Himalaya and their ecological significance Kiran Bargali Department of Botany, Kumaun University (K.U.) Nainital-263002, Uttarakhand, India. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 21 June, 2020 Actinorhizal plants are important in having symbiotic association with actinomycete Frankia. Nitrogen (N) fixation by actinorhizal plants is a major source of fixed N in diverse and widespread ecosystems including forests, bogs, swamps, coastal dunes, landslides, glacial deposits, shrublands, prairies and deserts. They play important roles in wild land ecosystem function and are used in land reclamation, range management, forestry, agroforestry and horticulture. In this study, 8 actinorhizal plants of Kumaun Himalayan region have been described. Habit, habitat, distribution and possible ecological significance of these plants are also described. These plants are not only important for the restoration of degraded lands, but also provide good source of timber, fuel wood, fodder, food and medicines, etc. Key words: Actinorhizal, degraded, nitrogen, plantation, reclamation. INTRODUCTION Frankia, a filamentous bacterium (actinomycete), forms In the present study, an attempt has been made to nodule like symbiotic associations with the roots of several identify the actinorhizal plants growing in Kumaun plant species known collectively as "Actinorhizal plant". The Himalayan region. The recent application of plant actinorhizal symbiosis have been reported in numerous nitrogen fixation in ecosystem is a key step to understand plants all over the word except Antartica (Baker and its implications in ecological conservation, and future Schwinterzer, 1990). -

Integrating Local Knowledge with Tree Diversity Analyses to Optimize On

Agroforest Syst (2019) 93:755–770 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-017-0172-8 Integrating local knowledge with tree diversity analyses to optimize on-farm tree species composition for ecosystem service delivery in coffee agroforestry systems of Uganda Hannington Bukomeko . Laurence Jassogne . Susan Balaba Tumwebaze . Gerald Eilu . Philippe Vaast Received: 16 December 2016 / Accepted: 5 December 2017 / Published online: 8 December 2017 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Coffee agroforestry systems deliver of importance to their livelihoods (‘Needs rank’) and ecosystem services (ES) critical for rural livelihoods ranked trees according to suitability for providing ES. like food but also disservices that constrain livelihoods Using Bradley Terry modeling, we grouped trees into like fostering coffee-pests. Since such ES are tree- ‘ES groups’ according to suitability for providing based, maximizing ES and limiting constraints different ES and ranked ‘ES groups’ according to tree requires knowledge on optimizing on-farm tree com- diversity (‘Diversity rank’). Tree-suitability for pro- position especially trees adapted to local conditions. viding ES and importance of ES to farmers varied with The study was in three sites along a rainfall gradient in rainfall regime but tree diversity did not match Central Uganda where we: assessed tree diversity in farmers’ needs for ES. We propose the FaD–FaN coffee agroforestry; ranked tree suitability for provid- (matching farm tree diversity to farmers’ needs) ing ES according to farmers’ knowledge; and then approach for optimizing tree species composition with proposed an approach for optimizing on-farm tree respect to tree-suitability for farmers’ priority ES. -

Rhus Coriaria

Rhus coriaria (Elm-Leaved Sumach, Sicilian sumac) " Every Lebanese has eaten the dark red condiment called summac, which is derived from the fruits of this tree and is used in popular foods such as the Mankouche, Kaakeh, and Fattoush.Summac tree is found in every part of the country, growing at almost every altitude. This small tree, composed of single or multiple slender trunks, reaches 2 to 3 meters in height.The Summac tree can grow in poor, rocky soils with little access to water; it is tolerant to drought and grows well along the coast, because it is also resistant to salt." from: Trees of Lebanon, 2014, Salma Nashabe Talhouk, Mariana M. Yazbek, Khaled Sleem, Arbi J. Sarkissian, Mohammad S. Al-Zein, and Sakra Abo Eid Landscape Information French Name: Le Sumac des corroyeurs ﺳﻤﺎﻕ :Arabic Name Plant Type: Shrub Origin: Southern Europe Heat Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Hardiness Zones: 8, 9, 10, 11 Uses: Medicinal, Native to Lebanon Size/Shape Growth Rate: Moderate Tree Shape: Spreading Canopy Symmetry: Irregular Canopy Density: Dense Plant Image Canopy Texture: Medium Height at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 m Spread at Maturity: 3 to 5 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 10 to 20 Years Rhus coriaria (Elm-Leaved Sumach, Sicilian sumac) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Whorled Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Deciduous Leaf Type: Odd Pinnately compund Leaf Blade: 5 - 10 cm Leaf Shape: Oval Leaf Margins: Serrate Leaf Textures: Hairy, Fine Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower -

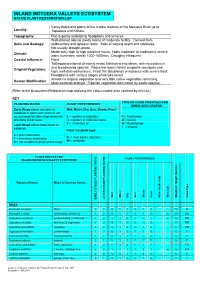

Inland Motueka Valleys Plant Lists

INLAND MOTUEKA VALLEYS ECOSYSTEM NATIVE PLANT RESTORATION LIST Valley floors and plains of the middle reaches of the Motueka River up to Locality: Tapawera and Kohatu. Topography: Flat to gently undulating floodplains and terraces. Well-drained alluvial sandy loams of moderate fertility. Derived from Soils and Geology: sedimentary and igneous rocks. Soils of varying depth and stoniness. Not usually drought-prone. Moderately high to high sunshine hours; frosts moderate to moderately severe; Climate: warm summers; rainfall 1200-1600mm. Droughts infrequent. Coastal influence: None Tall podocarp forest of mainly mataī, kāhikatea and tōtara, with mixed beech and broadleaved species. Red-silver beech forest on gentle toeslopes and Original Vegetation: high, well-drained terraces. Frost flat shrublands on terraces with severe frost. Floodplains with various stages of kānuka forest. Almost no original vegetation and very little native vegetation remaining. Human Modification: Most wetlands drained. Riparian vegetation dominated by exotic species. [Refer to the Ecosystem Restoration map showing the colour-coded area covered by this list.] KEY TYPE OF FOOD PROVIDED FOR PLANTING RATIO PLANT PREFERENCES BIRDS AND LIZARDS Early Stage plants are able to Wet, Moist, Dry, Sun, Shade, Frost establish in open sites and can act as a nursery for later stage plants by 1 = prefers or tolerates F = Fruit/seeds providing initial cover. ½ = prefers or tolerates some N = Nectar 0 = intolerant of B = Buds/foliage Later Stage plants need cover to I = Insects establish. -

Early Evolution of Coriariaceae (Cucurbitales) in Light of a New Early Campanian (Ca

TAXON 69 (1) • February 2020: 87–99 Renner & al. • Evolution of Coriariaceae SYSTEMATICS AND PHYLOGENY Early evolution of Coriariaceae (Cucurbitales) in light of a new early Campanian (ca. 82 Mya) pollen record from Antarctica Susanne S. Renner,1 Viviana D. Barreda,2 María Cristina Tellería,3 Luis Palazzesi2 & Tanja M. Schuster1 1 Systematic Botany and Mycology, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger-Straße 67, 80638 Munich, Germany 2 Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, Av. Ángel Gallardo 470, C1407DJR Buenos Aires, Argentina 3 Laboratorio de Sistemática y Biología Evolutiva, Museo de La Plata, La Plata, B1900FWA, Argentina Address for correspondence: Susanne S. Renner, [email protected] DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12203 Abstract Coriariaceae comprise only Coriaria, a genus of shrubs with nine species in Australasia (but excluding Australia), five in the Himalayas, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Japan, one in the Mediterranean, and one ranging from Patagonia to Mexico. The sister family, Corynocarpaceae, comprises five species of evergreen trees from New Guinea to New Zealand and Australia. This distribution has long fascinated biogeographers as potential support for Wegener’s theory of continental drift, with alternative scenarios invoking either Antarctic or Beringian range expansions. Here, we present the discovery of pollen grains from Early Campanian (ca. 82 Mya) deposits in Antarctica, which we describe as Coriaripites goodii sp. nov., and newly generated nuclear and plastid molecular data for most of the family’s species and its outgroup. This greatly expands the family’s fossil record and is the so far oldest fossil of the order Cucurbitales. We used the phylogeny, new fossil, and an Oligocene flowering branch assigned to a small subclade of Coriaria to gen- erate a chronogram and to study changes in chromosome number, deciduousness, and andromonoecy. -

I TREE ATTRIBUTE RANKING and PHENOLOGY STUDY: FARMERS

TREE ATTRIBUTE RANKING AND PHENOLOGY STUDY: FARMERS’ KNOWLEDGE OF TREES COMMONLY FOUND ON COFFEE FARMS BORDERING MABIRA FOREST RESERVE IN MUKONO DISTRICT, UGANDA BY MUCHELO RONALD W.OMELI AG332-0855/2009 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN RESAERCH METHODS OF JOMO KENYATTA UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY September 2011 i Declaration This dissertation is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University Sign: ______________________________ Date: ______________________ Muchelo Ronald Omeli Recommendation This dissertation has been submitted for examination with our approval as the supervisors of the candidate Sign: ______________________________ Date: ______________________ Dr. Samuel Mwalili JKUAT, Kenya Sign: ______________________________ Date: ______________________ Prof. Catherine Muthuri JKUAT, Kenya Sign: ______________________________ Date: ______________________ Prof. Fergus Sinclair ICRAF, Nairobi ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my sisters; Rachel and Sylvia iii Acknowledgment Great appreciation goes to RUFORUM for all the financial support through the scholarship and JKUAT for delivering the course. Special appreciation also goes to Professor Fergus Sinclair and Dr. Anja Gassner for allowing me to be part of their research team and continued technical support. Dr. Mwalili and Prof Muthuri in the same measure are greatly acknowledged. Thanks a lot for sparing your valuable time trying to make sure I am on the right track with this research. Your guidance and constant follow up of my progress has enabled me to make this progress. Appreciation also goes to Genevieve Lamond for and Emilie Smith for their assistance and guidance. Finally I would to extend my appreciation to, NAFORI, ICRAF and CAFNET project team for all the assistance they offered me during my entire time at the institution. -

Molecular Systematics of the Cashew Family (Anacardiaceae) Susan Katherine Pell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Molecular systematics of the cashew family (Anacardiaceae) Susan Katherine Pell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Pell, Susan Katherine, "Molecular systematics of the cashew family (Anacardiaceae)" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1472. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1472 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF THE CASHEW FAMILY (ANACARDIACEAE) A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Susan Katherine Pell B.S., St. Andrews Presbyterian College, 1995 May 2004 © 2004 Susan Katherine Pell All rights reserved ii Dedicated to my mentors: Marcia Petersen, my mentor in education Dr. Frank Watson, my mentor in botany John D. Mitchell, my mentor in the Anacardiaceae Mary Alice and Ken Carpenter, my mentors in life iii Acknowledgements I would first and foremost like to thank my mentor and dear friend, John D. Mitchell for his unabashed enthusiasm and undying love for the Anacardiaceae. He has truly been my adviser in all Anacardiaceous aspects of this project and continues to provide me with inspiration to further my endeavor to understand the evolution of this beautiful and amazing plant family. -

Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities Evaluation of Coriaria Myrtifolia from the North of Morocco

International Food Research Journal 24(2): 498-502 (April 2017) Journal homepage: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities evaluation of Coriaria myrtifolia from the North of Morocco 1,2Hafsé, M., 2,3Farah, A., 4Mouktadir, J. E. and 1*Fikri-Benbrahim, K. 1Microbial Biotechnology Laboratory. Faculty of Science and Technology. Saiss. Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University. Fez. Morocco 2National Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Taounate. Morocco 3Applied Organic Chemistry Laboratory, Faculty of Sciences and Techniques, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, P. O. Box 2202 Imouzzer Road, Fez, Morocco. 4Discourse, Society and Creativity: Perception and Implications Laboratory. Faculty of Arts and Humanities Saiss. Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University. Fez. Morocco Article history Abstract Received: 1 January 2016 The present study has examined the chemical composition and evaluated the pharmacological Received in revised form: activities of the ethyl acetate extract of Coriaria myrtifolia. The antioxidant activity was 17 April 2016 Accepted: 21 April 2016 determined by using the diphenyl-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) test, and the anti-inflammatory activity was evaluated by using the plantar edema model induced in rabbits by carrageenan. The extract has revealed a significant free-radical scavenging capacity. The plant IC50 value of Keywords 0.016 mg/ml was found less than stated with the Butylated hydroxyl-toluene (BHT) standard (0.025 mg/ml). Administration of the ethyl acetate extract at a dose of 0.013mg/kg wb inhibits Coriaria myrtifolia Chemical composition completely the inflammation. These results have indicated that the C. myrtifolia leaves Antioxidant activity contains bioactive compounds and have a high antioxidant activity as well as interesting anti- Anti-inflammatory activity inflammatory properties, suggesting the usefulness of their extracts to prevent oxidative and inflammatory processes. -

Pharmacological and Antioxidant Activities of Rhus Coriaria L. (Sumac)

antioxidants Review Pharmacological and Antioxidant Activities of Rhus coriaria L. (Sumac) Halima Alsamri 1, Khawlah Athamneh 1,2, Gianfranco Pintus 3,4 , Ali H. Eid 5,6 and Rabah Iratni 1,* 1 Department of Biology, College of Science, United Arab Emirates University, Al-Ain 15551, UAE; [email protected] (H.A.); [email protected] (K.A.) 2 Department of Chemistry, College of Arts and Sciences, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi 127788, UAE 3 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah 27272, UAE; [email protected] 4 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sassari, Viale San Pietro 43, 07100 Sassari, Italy 5 Department of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha 2713, Qatar; [email protected] 6 Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Research Unit, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha 2713, Qatar * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +971-3-713-6526; Fax: +971-3-7134-927 Abstract: Rhus coriaria L. (Anacardiaceae), commonly known as sumac, is a commonly used spice, condiment, and flavoring agent, especially in the Mediterranean region. Owing to its bountiful beneficial values, sumac has been used in traditional medicine for the management and treatment of many ailments including hemorrhoids, wound healing, diarrhea, ulcer, and eye inflammation. This plant is rich in various classes of phytochemicals including flavonoids, tannins, polyphenolic compounds, organic acids, and many others. By virtue of its bioactive, Rhus coriaria possesses power- ful antioxidant capacities that have ameliorative and therapeutic benefits for many common diseases including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. This review describes the phytochemical properties of R. -

Anthocyanin Composition of the Fruit of Coriaria Myrtifolia L

PHYTOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS Phytochem. Anal. 13, 354–357 (2002) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/pca.667 Anthocyanin Composition of the Fruit of Coriaria myrtifolia L. Marı´a Teresa Escribano-Bailo´n,1 Celestino Santos-Buelga,1 Gonzalo L. Alonso2 and Marı´a Rosario Salinas2* 1Laboratorio de Nutricio´n y Bromatologı´a, Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad de Salamanca, E-37007 Salamanca, Spain 2Ca´tedra de Quı´mica Agrı´cola, ETSI Agro´nomos, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, E-02071 Albacete, Spain The anthocyanin composition of the fruit of Coriaria myrtifolia L. and the changes which occur during ripening were studied using HPLC-PAD and LC-MS. Ten anthocyanins were detected and identified by their absorption and mass spectra as the 3-glucoside and 3-galactoside derivatives of delphinidin, cyanidin, petunidin, peonidin and malvidin. Fruit ripening was accompanied by substantial changes in the anthocyanin profile, with methoxylated anthocyanins, i.e. malvidin and peonidin, predominating in the final stages of ripening, and the trihydroxylated anthocyanin, delphinidin, during the earlier stages. Furthermore, galactoside derivatives were more abundant than glucosides in the ripe fruit. At full maturity, the fruits of C. myrtifolia were very rich in anthocyanins with a content of 10.7% (on a dry weight basis), a level which is higher than that found in most fruits usually considered to be anthocyanin-rich. The ability to grow C. myrtifolia in damaged and nitrogen poor soils, together with the possibility of using this plant for the extraction of anthocyanin, makes it ideal for consolidating soils and repopulating semi-desert or fire-damaged areas. -

Seed Shape Quantification in the Order Cucurbitales

ISSN 2226-3063 e-ISSN 2227-9555 Modern Phytomorphology 12: 1–13, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1174871 RESEARCH ARTICLE Seed shape quantification in the order Cucurbitales Emilio Cervantes 1, 2*, José Javier Martín Gómez 1 1 Instituto de Recursos Naturales y Agrobiología de Salamanca-Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (IRNASA–CSIC), Cordel de Merinas 40, 37008 Salamanca, Spain; * [email protected] 2 Grupo de Investigación Reconocido Bases Moleculares del Desarrollo, Universidad de Salamanca (GIR BMD-USAL), Edificio Departamental, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain Received: 03.10.2017 | Accepted: 23.01.2018 | Published: 17.02.2018 Abstract Seed shape quantification in diverse species of the families belonging to the order Cucurbitales is done based on the comparison of seed images with geometric figures. Quantification of seed shape is a useful tool in plant description for phenotypic characterization and taxonomic analysis. J index gives the percent of similarity of the image of a seed with a geometric figure and it is useful in taxonomy for the study of relationships between plant groups. Geometric figures used as models in the Cucurbitales are the ovoid, two ellipses with different x/y ratios and the outline of the Fibonacci spiral. The images of seeds have been compared with these figures and values of J index obtained. The results obtained for 29 species in the family Cucurbitaceae support a relationship between seed shape and species ecology. Simple seed shape, with images resembling simple geometric figures like the ovoid, ellipse or the Fibonacci spiral, may be a feature in the basal clades of taxonomic groups. -

Tmd'a Woody Plant List Forl@Tlgua and Barbuda

Tmd’a Woody Plant list for l@tlgua and Barbuda: Past and Present John Francis, Cados Riira, and Julio Figurema S_ Durina;thel7thandl8~centuriea,theielandofAntiguawas~~ foragri~.viuauyalloftheremaining foresbwemcutover,grazed,and bumed.Sincethe aba&mentofaugamne~vati~xnuchofthelandhas retunledtQsecondaryf&.BarbudasufferedmeiIllyfromovercuttiIlgand overgrazing begiming in the 17th century. Very heavy grazing preamre con- tinues in ISarbuda. l&spit23 great d&W, a mqjority of the native qe45ee remainrmbothislande.Lista0fnativeandexoticepecieaarep~~bere.A prote&i~plansbauldbe~hedforsevleralareasmboth~ Tk~ward a Woody Plant List for Antigua and Barbuda: Past and Present John Francis, Carlos Rivera, and Julio Figureroa INTRODUCTION AND HISTORY hectares of Antigua to grow up as secondary forest while sparing the pre-existing secondary forest from Antigua and Barbuda are two small islands with a further disturbance. total area of 440 km2 located in the Lesser Antilles in English attempts to settle Barbuda began in 1628 the eastern Caribbean. Although not differing greatly and continued intermittently with attacks of the in size and separated by only 50 km, the origin and Caribs and French until early in the 18th century. The physiography of the islands are quite different. Antigua small island community subsisted for almost three cen- was formed by vulcanism more than 40 million years turies by raising livestock. During this period, vir- ago during the Eocene. The rock foundation of Bar- tually every tree large enough to use for construction buda is entirely of Pleistocene limestone. A land bridge materials was felled. Grazing must have been intense, apparently connected the two islands during the and fuelwood cutting heavy, at least near Codrington, Pleistocene (Schuchert 1935).