Punishment and Crime the Reverse Order of Causality in the White Ribbon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires

CAPTURING THE DEVIL The real story of the capture of Adolph Eichmann Based on the memoirs of Peter Zvi Malkin A feature film written and directed by Philippe Azoulay PITCH Peter Zvi Malkin, one of the best Israeli agents, is volunteering to be part of the commando set up to capture Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires. As the others, he wants to take revenge for the killing of his family, but the mission is to bring Eichmann alive so that he may be put on trial in Jerusalem. As Peter comes to consider his prisoner an ordinary and banal being he wants to understand the incomprehensible. To do so, he disobeys orders. During the confrontation between the soldier and his prisoner, a strange relationship develops… CAPTURING THE DEVIL HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1945 The Nuremberg trial is intended to clear the way to for the rebuilding of Western Europe Several Nazi hierarchs have managed to hide or escape Europe 1945 Adolph Eichmann who has organized the deportations and killings of millions of people is hiding in Europe. 1950 Eichmann is briefly detained in Germany but escapes to South America thanks to a Red Cross passport. In Europe and in Israel, Jews who survived the camps try to move into a new life. The young state of Israel fights for its survival throughout two wars in 1948 and 1956. The Nazi hunt is considered a “private“ matter. 1957 the Bavarian General Attorney Fritz Bauer, who has engaged into a second denazification of Germany’s elite, gets confirmation that Eichmann may be located in Argentina. -

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Alles Wird Gut

ALLES WIRD GUT a film by PATRICK VOLLRATH www.everythingwillbeokay-film.com CONTENTS Overview ...........................................................................................................3 Synopsis ...............................................................................................................3 About the movie............................................................................................4 Cast ........................................................................................................................5 Crew .....................................................................................................................6 CV Leading Actors ........................................................................................7 Director & Producer ....................................................................................8 Contact ................................................................................................................9 www.everythingwillbeokay-film.com EVERYTHING WILL BE OKAY SYNOPSIS ALLES WIRD GUT Country: Germany / Austria A divorced father picks up his eight-year-old daughter Lea. It Language: german seems pretty much like every second weekend, but after a while Year: 2015 Lea can‘t help feeling that something isn‘t right. Runtime: 30 min So begins a fateful journey. Framerate: 24 fps Ratio: 2,35:1 Format: 2K DCP Subtitles: english, french Sound: 5.1 Dolby Digital Genre: Drama / Thriller Form: Narrative Fiction Short Film Shooting days: 6 Location: -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Every Child Survives and Thrives

GOAL AREA 1 Every child survives and thrives Global Annual Results Report 2019 Cover image: © UNICEF/UN0317965/Frank Dejongh Expression of thanks: © UNICEF/UN0303648/Arcos A mother is washing and cuddling her baby, in the village of On 23 April 2019, in Cucuta in Colombia, a baby undergoes a health Tamroro, in the centre of Niger. check at the UNICEF-supported health centre. In Niger, only 13 percent of the population has access to basic sanitation services. Expression of thanks UNICEF is able to support the realization of children’s rights and change children’s lives by combining high-quality programmes at scale, harnessing innovation and collecting evidence, in partnership with governments, other United Nations organizations, civil society, the private sector, communities and children. It leverages wider change nationally and globally through advocacy, communications and campaigning. UNICEF also builds public support around the world, encouraging people to volunteer, advocate and mobilize resources for the rights and well-being of children, and works with a wide range of partners to achieve even greater impact. UNICEF’s work is funded entirely through the voluntary support of millions of people around the world and our partners in government, civil society and the private sector. Voluntary contributions enable UNICEF to deliver on its mandate to support the protection and fulfilment of children’s rights, to help meet their basic needs, and to expand their opportunities to reach their full potential. We wish to take this opportunity to express deeply felt appreciation to all our many and varied resource partners for support to Goal Area 1 in 2019, and particularly those that were able to provide thematic funding. -

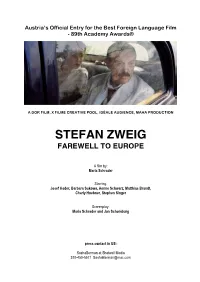

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Titel Kino 1 2000, Endversion

EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 1/2000 GERMAN MASTERS Schlöndorff, Thome and Wenders in Competition at the Berlin International Film Festival Special Report SELLING GERMAN FILMS Spotlight on GERMAN TV-MARKETS Kino Scene from:“THE MILLION DOLLAR HOTEL” Thanks to our national and international customers subtitling film video dvd 10 years of Film und Video Untertitelung dubbing post-production 10 years of high-quality subtitles editing telecine 10% reduction on our regular prices standard conversion video transfer inspection of material during 10 celebratory months graphic design from 10 July 1999 to 10 May 2000 dvd mastering you will see the difference www.untertitelung.de [email protected] tel.: +49-2205/9211-0 fax: +49-2205/9211-99 www. german- cinema. de/ INFORMATION ON GERMAN FILMS. now with links to international festivals! Export-Union des Deutschen Films GmbH Tuerkenstrasse 93 · D-80799 München · phone +49-89-39 00 95 · fax +49-89-39 52 23 · email: [email protected] KINO 1/2000 6 Selling German Films 25 In Competition at Berlin Special Report 25 The Million Dollar Hotel 10 Opening Reality OPENING FILM Wim Wenders For Illusions 26 Paradiso – Sieben Tage mit Portrait of Director Sherry Hormann sieben Frauen PARADISO 11 ”I Sold My Soul To Rudolf Thome The Cinema“ 27 Die Stille nach dem Schuss Portrait of Director Tom Tykwer RITA’S LEGENDS Volker Schlöndorff 12 Purveyors Of Excellence Cologne Conference 13 German TV Fare Going Like Hot Cakes German Screenings 15 A Winning Combination Hager Moss Film 16 KINO news 28 German -

Pressure of the Group, Who Were Infected with Hatred of the Supposed Enemy, and Thought It Was Their Duty to Commit These Deeds

02 RADICAL EVIL INHALT Brief Synopsis PAGE 03 Statement by Stefan Ruzowitzky PAGE 04 Questions and Food for Thought PAGE 06 „Radical evil is something that should not have happened, i.e. that we cannot Contents PAGE 07 be reconciled to, that we cannot accept Production notes PAGE 10 as fate under any circumstances, and that we cannot pass by in silence.“ Interview with Stefan Ruzowitzky PAGE 11 Hannah Arendt The Psychology of the Perpetrators PAGE 16 Socio-psychological Experiments PAGE 19 The Filmmakers PAGE 21 Credits PAGE 24 RADICAL EVIL 03 Following upon his Oscar®-winning feature flm „The Counterfeiters“ Stefan Ruzowitzky takes up the theme once again in his new non-fction drama „Radical Evil“. BRIEF SYNOPSIS How do normal young men turn into mass murde- Using a stylistically innovative approach, Stefan rers? Why do respectable family men kill women, Ruzowitzky‘s nonfction-drama „Radical Evil“ tells children and babies, day in and day out, for years? of the systematic shooting of Jewish civilians by Why do so few of them refuse to follow orders, al- German death squads in Eastern Europe and sear- though they are given the option? ches for the root of evil. We hear the thoughts of the perpetrators in letters, diaries and court reports, we look into young faces that are projection screens for our associations and insights. Supplemented by historical photographs, the sta- tements of widely renowned researchers , such as Père Desbois, Christopher Browning or Robert Jay Lifton, and with the surprising results of psycholo- gical experiments, the flm leads us to „radical evil“, a blueprint for genocide. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ew riter face, while others may be fi’om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improperalig n m ent can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9420996 Music in the black and white conununities in Petersburg, Virginia, 1865—1900 Norris, Ethel Maureen, Ph.D.