Mozambique Livelihood Baseline Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Mozambique Melq Gomes

January 2014 Tracking Adaptation and Measuring Development (TAMD) in Mozambique Melq Gomes Q3 Report - Feasibility Testing Phase MOZAMBIQUE TAMD FEASIBILITY STUDY QUARTER THREE REPORT, 10/01/2014 Contents INTRODUCTION 2 STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS/KEY ENTRY POINTS 8 THEORY OF CHANGE ESTABLISHED 9 INDICATORS (TRACK 1 AND TRACK 2) AND METHODOLOGY 14 National level indicators 14 District level indicators 15 METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH 16 EMPIRICAL DATA COLLECTION (a) TRACK 1 (b) TRACK 2 16 CHALLENGES 17 CONCLUSIONS AND EMERGING LESSONS 17 ANNEXES 18 Annex 1: National level indicators 18 Annex 2: Guijá Field Work Report – Developing the ToC. 18 Annex 3: Draft of the workplan for Mozambique. 18 www.iied.org 1 MOZAMBIQUE TAMD FEASIBILITY STUDY QUARTER THREE REPORT, 10/01/2014 INTRODUCTION 1.1 - Mozambique Context Summary: Mozambique is the 8th most vulnerable country to climate change and is one of the poorest countries in the world with a high dependency on foreign aid. The population is primarily rural and dependent on agriculture, with 60% living on the coastline. Droughts, flooding and cyclones affect particular regions of the country and these are projected to increase in frequency and severity. The main institution for managing and coordinating climate change responses is the Ministry for Coordination of Environment Affairs (MICOA), the Ministry for Planning and Development also has a key role. New institutions have been proposed under the National Strategy on Climate Change but are not yet operational, it was approved in 2012. (Artur, Tellam 2012:8) Mozambique Climate Vulnerability and future project effects (Artur, Tellam 2012:9) Summary: The main risk/hazards in Mozambique are floods, droughts and cyclones with a very high level of current and future vulnerability in terms of exposure to floods and cyclones as more than 60% of the population lives along the coastline below 100 meters of altitude. -

Chibuto Xai-Xai Guija

¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ ¥¦ 28 January 2011 Version 1.0 Heavy Rainfall & Flooding !!, Glide No: FL-2011-000013-MOZ Rainfall Total (10 - 25 January 2011) ¥¦ L E N N 24°15'S MAHUNGO 24°15'S A H C Zimbabwe E Mozambique 33°30'E U Q I B M A Z 33°35'E MAQUEZE O ") M 33°25'E CHIWANGA M'BOCHOA 24°20'S 24°20'S South Africa ¥¦ ") 33°20'E ¥¦ CUCUMUCA Map Information This map illustrates satellite-detected flood waters over the affected districts of Chibuto & Xai-Xai of 33°15'E FUNGUANE MAJECUZA Gaza Province, Mozambique. Flooded areas have been marked as Red representing standing flood 24°25'S waters identified with a high degree of confidence. -

Charcoal Supply Chains from Mabalane to Maputo: Who Benefits?

Energy for Sustainable Development 33 (2016) 129–138 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Energy for Sustainable Development Charcoal supply chains from Mabalane to Maputo: Who benefits? Sophia Baumert a,⁎, Ana Catarina Luz b,JanetFisherc, Frank Vollmer c, Casey M. Ryan c, Genevieve Patenaude c, Pedro Zorrilla-Miras c,LuisArtura, Isilda Nhantumbo d, Duncan Macqueen d a Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Mozambique b cE3c – Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal c The University of Edinburgh, UK d International Institute for Environment and Development, UK article info abstract Article history: In urban centres of Mozambique, charcoal is the major energy source for cooking. Growing demand drives high Received 14 November 2015 wood extraction rates over increasing areas of miombo and mopane woodlands. Charcoal production can lead to Revised 13 May 2016 changes in ecosystem service provision and woodland degradation while also significantly contributing to rural Accepted 8 June 2016 income and, possibly, poverty alleviation. As such, understanding charcoal production and trade has important Available online xxxx implications for rural areas and for the sustainable development of woodland resources. Here, we investigate charcoal production and trade through empirical research conducted in Gaza Province, the main charcoal supply Keywords: Value chain analysis area for Maputo, Mozambique. Mopane woodland We analyse the present structure of the main charcoal supply chains from Gaza province to Maputo and the profit Licencing system distribution along them. Seven villages in the Mabalane district, Gaza, at different stages of engagement with the Mozambique charcoal industry, were selected for investigation. We conducted household surveys and semi-structured inter- Forest law views with key informants (village leaders, charcoal producers, licence holders, wholesalers, transporters and Community-based natural resource forest technicians), from May to October 2014. -

Projectos De Energias Renováveis Recursos Hídrico E Solar

FUNDO DE ENERGIA Energia para todos para Energia CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFÓLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES Edition nd 2 2ª Edição July 2019 Julho de 2019 DO POVO DOS ESTADOS UNIDOS NM ISO 9001:2008 FUNDO DE ENERGIA CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR RENEWABLE ENERGY PROJECTS PORTFOLIO HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES FICHA TÉCNICA COLOPHON Título Title Carteira de Projectos de Energias Renováveis - Recurso Renewable Energy Projects Portfolio - Hydro and Solar Hídrico e Solar Resources Redação Drafting Divisão de Estudos e Planificação Studies and Planning Division Coordenação Coordination Edson Uamusse Edson Uamusse Revisão Revision Filipe Mondlane Filipe Mondlane Impressão Printing Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Leima Impressões Originais, Lda Tiragem Print run 300 Exemplares 300 Copies Propriedade Property FUNAE – Fundo de Energia FUNAE – Energy Fund Publicação Publication 2ª Edição 2nd Edition Julho de 2019 July 2019 CARTEIRA DE PROJECTOS DE RENEWABLE ENERGY ENERGIAS RENOVÁVEIS PROJECTS PORTFOLIO RECURSOS HÍDRICO E SOLAR HYDRO AND SOLAR RESOURCES PREFÁCIO PREFACE O acesso universal a energia em 2030 será uma realidade no País, Universal access to energy by 2030 will be reality in this country, mercê do “Programa Nacional de Energia para Todos” lançado por thanks to the “National Energy for All Program” launched by Sua Excia Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, Presidente da República de Moçam- His Excellency Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, President of the -

Adaptation to Climate Change in Semi-Arid Environments of Mozambique

ENVIRONMENTENVIRONMENT [CLIMATE AND NATURAL CHANGE] RESOURCESBIOENERGY MANAGEMENTMONITORING AND ASSESSMENT SERIES(1) Front cover photosLeft: FAO Mozambique Middle: FAO Mozambique J.7 Right: FAO Mozambique Back cover photosLeft: FAO Mozambique /diddle: FAO Mozambique Right FAO Mozambique Background image in this pageIllustration elaborated from "L'Encyclopedie Diderot et D'Alembert" Copies of FA0 publications can be requested fromSales and Marketing Group - Communication Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Viale delle Terme di Caracalla -00153 Rome, Italy E-mail:[email protected] Fax:(+39) 06 57053360 Web slte:http://www.fao.org Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Mozambique Experience and Lessons from Environments Change in Semi-Arid Adaptation to Climate Mozambique Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Maputo, Andrew Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy Alemneh OneWorld Sustainable Investments, Cape Town, South Africa Stephanie M D attick M ejene idgley G M overnment of ozambique Rome, 2012 19 ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT SERIES ENVIRONME NT [ CLIMATE CHANGE ] BIOENERGY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Guidance Notes for Preparing Livelihood Zone Profiles

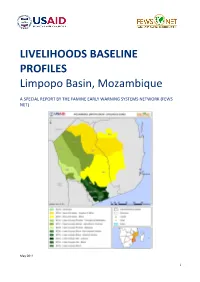

LIVELIHOODS BASELINE PROFILES Limpopo Basin, Mozambique A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) May 2011 1 LIVELIHOODS BASELINE PROFILES Limpopo Basin, Mozambique A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) May 2011 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 2 Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Sorghum Dominant Semi Arid Interior Livelihood Zone................................................................................ 5 Maize Dominant Semi-Arid Interior Livelihood Zone .................................................................................. 11 Upper Limpopo Riverine Chicualacuala/Mabalane Livelihood Zone .......................................................... 19 Upper Limpopo Massingir Riverine Livelihood Zone ................................................................................... 25 Lower Limpopo Baixa Non Irrigation Scheme Livelihood Zone ................................................................... 32 Lower Limpopo Baixa Irrigation Livelihood Zone ........................................................................................ 39 Lower Limpopo Alta Cassava Livelihood Zone ............................................................................................ 46 Lower -

End Smear Campaign Against Bishop Lisboa

First UA:132/20 Index: AFR 41/2914/2020 Mozambique Date: 26 August 2020 URGENT ACTION END SMEAR CAMPAIGN AGAINST BISHOP LISBOA Bishop Don Luis Fernando Lisboa of Pemba city, in Northern Mozambique, has been the subject of an ongoing smear campaign to undermine and delegitimize his vital human rights work in the province of Cabo Delgado. President Nyusi, and government affiliates, have directly and indirectly singled out Bishop Lisboa in their critique of dissidents. The authorities must ensure a safe and enabling environment for Bishop Lisboa to continue his human rights work without fear of intimidation, harassment and any reprisals. TAKE ACTION: WRITE AN APPEAL IN YOUR OWN WORDS OR USE THIS MODEL LETTER President Filipe Jacinto Nyusi President of the Republic of Mozambique Address: Avenida Julius Nyerere, PABX 2000 Maputo – Mozambique Hounorable President Filipe Nyusi, I am writing to you concerning the ongoing smear campaign against human rights defender (HRD), Bishop Don Luis Fernando Lisboa, of Pemba city. On 14 August, in a press conference you gave in Pemba city, the capital of the Cabo Delgado province, you lamented those ‘foreigners’, who freely choose to live in Mozambique, of using human rights to disrespect the sacrifice of those who keep this young homeland. This statement triggered an onslaught of attacks on social media against Bishop Lisboa and his human rights work, with many users accusing Bishop Lisboa of associating with terrorists and insurgents. Furthermore, on 16 August, Egidio Vaz, a well-known government affiliate referred to Bishop Lisboa on his social media platform as “a criminal [who] should be expelled from Mozambique”. -

Adaptive Governance for a Changing Climate: Government, Communities

ACCRA CASE STUDY JUNE 2017 ADAPTIVE GOVERNANCE FOR A CHANGING CLIMATE Government, communities and others working collaboratively in Mozambique to transform climate adaptation planning systems Community members validating their local adaptation plan with district government officials and ACCRA team in Guija district, Mozambique. Photo: Thomas White In Mozambique, climate change has been increasing the vulnerability of rural and urban communities. Droughts, floods and cyclones are more frequent and severe, and sea- levels continue to rise – and the situation is likely to worsen. This has undermined the government’s efforts to achieve its goal of reducing extreme poverty. The approval of the new National Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Strategy (ENAMMC) in 2012 presented an important opportunity for ACCRA to advise the Government of Mozambique and ultimately to effect systemic and institutional change in planning for climate change adaptation. ACCRA also supported MITADER, which is responsible for operationalizing the strategy, with tools, resources and advice on processes. This story of change was developed following an external evaluation of ACCRA’s work in Mozambique, through a series of interviews and a learning history workshop held in October 2016 in Maputo. CONTENTS About ACCRA ............................................................................................................ 3 About this story of change ........................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1 The context and key actors: mozambique -

Ministry of Public Works, Housing and Water Resources

SFG3872 Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF PUBLIC WORKS, HOUSING AND WATER RESOURCES NATIONAL DIRECTORATE FOR MANAGEMENT OF WATER RESOURCES Public Disclosure Authorized EMERGENCY RESILIENT RECOVERY PROJECT - ADDITIONAL FINANCING (ERRP - AF) ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized July, 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized LIST OF ACRONYMS AIAS Water Supply and Sanitation Infrastructure Administration ARA Regional Water Administration DINOTER National Directorate of Territorial Planning and Resettlement DIPLAC-CEE National Directorate of Planning and Cooperation – School Construction and Equipment DNDR National Directorate of Rural Development DNFFB National Directorate of Forests and Fauna DNGRH National Directorate for the Management of Water Resources DPASA Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Food Security DPC Provincial Directorate of Culture DPOPHRH Provincial Directorate of Public Works, Housing and Water Resources DPS Provincial Directorate of Health DPTADER Provincial Directorate of Land, Environment and Rural Development DRM Disaster Risk Management DRR Disaster Risk Reduction EA Environmental Assessment EFP Environmental Focal Point EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EO Environmental Officer ERRP Emergency Resilient Recovery Project for the Northern and Central Regions ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESSP Education Sector -

MOZAMBIQUE Mvam Bulletin #6: January 2017

MOZAMBIQUE mVAM Bulletin #6: January 2017 Maize meal and rice prices remain high in Tete province Key points: Maize meal and rice remained very expensive in Tete province in January Maize grain is available in all markets except in Gaza Prices for rice and cooking oil are well above the provincial WFP/David Orr averages in Xai-Xai (Gaza) and Chibabava (Sofala) WFP/NaomiWFP/ Riccardo Scott Franco Methodology Food Security Outlook WFP/ David Orr The January survey was conducted using live calls for a sample of 116 traders across 29 districts in the provinces of Gaza, Tete, Seasonal deficits and price increases have been observed for most cereals Manica, Maputo, Sofala and Inhambane. The questions focused on across the country. Prices continue to increase as the lean season the prices of basic foods such as maize grain, maize meal, imported rice, cowpeas and cooking oil, with an open-ended question to progresses. The high demand for foods – especially for cereals – is likely to gauge traders’ perception of the food security situation in their lead to price hikes (source: FEWS NET). The high prices could coincide with areas. However, some of the traders who generally sell these items falling purchasing power and a lack of physical access to markets caused by had no stocks at the time of the calls. Consequently, many of the heavy rains in most parts of the country. At the peak of the rainy season, reported averages are based on fewer than three observations per flooding is expected in localized areas and along major flood plains. The district (Table 1). -

Mozambique Suffers Under Poor WASH Facilities and Is Prone MOZAMBIQUE to Outbreaks of Water- and Vector-Borne Diseases

ACAPS Briefing Note: Floods Briefing Note – 26 January 2017 Priorities for WASH: Provision of drinking water is needed in affected areas. humanitarian Mozambique suffers under poor WASH facilities and is prone MOZAMBIQUE to outbreaks of water- and vector-borne diseases. intervention Floods in central and southern provinces Shelter: Since October 2016, 8,162 houses have been destroyed and 21,000 damaged by rains and floods. Health: Healthcare needs are linked to the damage to Need for international Not required Low Moderate Significant Major healthcare facilities, which affects access to services. At least assistance X 30 healthcare centres have been affected. Very low Low Moderate Significant Major Food: Farmland has been affected in Sofala province, one of Expected impact X the main cereal-producing areas of a country where 1.8 million people are already facing Crisis (IPC Phase 3) levels of food Crisis overview insecurity. Since the beginning of January 2017, heavy seasonal rains have been affecting central Humanitarian Several roads and bridges have been damaged or flooded in the and southern provinces in Mozambique. 44 people have died and 79,000 have been constraints affected provinces. Some areas are only accessible by boat, and affected. The Mozambican authorities issued an orange alert for the provinces of aid has to be airdropped. Maputo, Gaza, Inhambane and Nampula, yet areas of Tete and Sofala provinces have also been affected. The orange alert means that government institutions are planning for an impending disaster. Continued rainfall has been forecasted for the first quarter of 2017. Key findings Anticipated The impact will be influenced by the capacity of the government to respond. -

Emergency Appeal Operation Update Mozambique: Storm and Cyclone

Emergency appeal operation update Mozambique: Storm and Cyclone Emergency appeal n° MDRMZ009 GLIDE n° TC-2012-000008-MOZ 6-month summary update 14 November 2012 Period covered by this Operations Update: 22 February to 31 October 2012. Appeal target (current): CHF 2,728,741 Appeal coverage: 39% <click here to go directly to the updated donor response report > Appeal history: • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 297,349 was initially allocated from the IFRC’s DREF to support the National Society to respond. • This Emergency Appeal was launched on 22 February 2012 for CHF 2,728,741 to support the Mozambique Red Cross Society to assist 14,000 households (70,000 beneficiaries) for 12 months. • This operation update provides information on Red Cross volunteers carrying out hygiene promotion in the progress of the operation and is meant to Namacurra district, Zambezia province/Photo: CVM satisfy the requirement for a summary of the first 6 months. Summary: In January 2012, two tropical storms and cyclones hit Mozambique. Tropical Cyclone Funso affected the Northern Coast of the country, while Storm Dando affected mostly Gaza and Maputo provinces. In response to the disaster, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) supported Mozambique Red Cross Society (CVM), through the deployment of a Regional Disaster Response Team (RDRT) consisting of water and sanitation, logistics, communication and coordination specialists in February for 10 days. A Field Assessment and Coordination Team (FACT) comprised of