WORK in PROGRESS Behm 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 079 711 TITLE Reading Language Arts

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 079 711 CS 000 .670 TITLE Reading Language Arts Curriculum Guide, Grades 1-2-3, Book Two.. INSTITUTION Vermilion Parish School Board, Abbeville, La. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 128p.. EDRS PRICE ME -$0.65 HC-S6.58 DESCRIPTORS Beginning Reading; *Curriculiu Guides; *Developmental Reading; *Primary Grades; Reading; Reading Improvement; Reading Instruction; Reading Materials; *Reading Programs; *Reading Skills - IDENTIFIERS Elementary Secondary Education Act Title III ABSTRACT This language arts curriculum guide focuses primarily on reading instruction for students in grades one, two,and three. The topics discussed in this guide include an introduction to reading; major steps in developmental reading instruction; suggested time allotments for the Ginn Reading Program; scope and sequence charts; a checklist -for evaluating progress in reading; a guide for the use of supplementary material; grouping for effective reading instruction; experience and enrichment charts in a reading program; suggested activities and games; and the use of the overhead projector- in reading instruction..A bibliography of professional and instructional books is also included..(WR) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION A WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT 01FICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Y° READING GRADES 1-2-3 p4 'VERMILION PARISH LANGUAGE ARTS CURRICULUM GUIDE 1970 -

A Memoir and Writing Family Love: Autobiographical Novel to Memoir, an Exegesis

FAMILY LOVE: A MEMOIR AND WRITING FAMILY LOVE: AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NOVEL TO MEMOIR, AN EXEGESIS JUDY ROSEMARY SCOTT (ka Rosie) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for The degree of Doctor of Creative Arts In College of Arts School of Humanities and Languages UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY AUSTRALIA (2006) ABSTRACT When I first started thinking about writing Family Love I wanted to write it as an autobiographical novel. This meant a radical departure from my usual writing methods. For one thing, it was the first time in my writing life that I was interested in the conscious use of a period in my life as material for a novel. I had never before attempted this and felt a certain amount of apprehension in abandoning tried and true approaches for something so new and risky. The label, autobiographical novel, seemed to define most accurately for the purposes and process of the thesis what were in fact a series of decisions, vacillations and rationalisations. An autobiographical novel seemed the best form for what I wanted from Family Love, a book that combined the fictional momentum and surprises of a novel with the added depth of personal and political material consciously drawn from real life and living people. I believed that the detailed evocation of a specific time and place my childhood and early adolescence in Sandringham and Titirangi in New Zealand, aided by diaries and memory would allow the story to follow its own fictional bent, and to have the emotionally truthful resonance of fiction without necessarily being completely factual. Writing Family Love: Autobiographical novel to memoir 1 Introduction............................................................................................................2 2 Definition of an Autobiographical novel ................................................................12 3 The ‘Commentary’ ................................................................................................18 4. -

The History of Tippecanoe County Compiled by Quinten Robinson, Tippecanoe County Historian the SETTING Tippecanoe County, Locate

The History of Tippecanoe County Compiled by Quinten Robinson, Tippecanoe County Historian THE SETTING Tippecanoe County, located in west-central Indiana, is about 65 miles northwest of Indianapolis and 100 miles southeast of Chicago. Tippecanoe County is 21 miles east to west and 24 miles north to south and Lafayette, the county seat, is situated on the banks of the Wabash nearly in the center. About one-half the surface consists of broad, fertile, and nearly level plains. The balance consists of gently rolling uplands, steep hillsides or rich alluvial bottoms. Occasional wetlands or bogs are found but those were largely drained by the beginning of the 20th century. The Wabash River flows nearly through the middle of Tippecanoe County from northeast to southwest. Tributaries to the Wabash River that drain the north and west parts of Tippecanoe County are the Tippecanoe River, Burnett Creek, Indian Creek, and Little Pine Creek. Draining the south and east parts of the county are Sugar Creek, Buck Creek, North, South and Middle Forks of the Wildcat Creek, Wea Creek, and Flint Creek. Besides Lafayette, cities and towns in Tippecanoe County are West Lafayette, the home of Purdue University, Battle Ground, West Point, Otterbein, Dayton, Clarks Hill, Romney, Stockwell, Americus, Colburn & Buck Creek. In 2010 county population was set at 172,780 PREHISTORIC TIPPECANOE COUNTY The terrain, the Wabash River, and the creeks you see today in Tippecanoe County came to their present condition about 10,000 years ago as the last continental glacier retreated northward leaving a vastly different landscape than what had existed before the advance of the ice sheets began over 700,000 years ago. -

Maycatweb Setup

WELCOME TO THE WEST KENTUCKY HORSE SALE, INC. westkentuckyhorsesales.com AUCTIONEERS Harold Brown . Florida Wayne Boyd, Jr . Kentucky RING MEN Jason Singleton . Kentucky Billy Stallion . Kentucky SALES MANAGER WEST KENTUCKY HORSE SALES, INC. Wayne Boyd, Jr., Diane Boyd, Bradley Boyd and Alaina Boyd 10545 Hwy. 62 West Princeton, Ky. 42445 Phone 270-365-7272 Be sure to confirm the correct hip number and price before you sign. Please print your name and address clearly since this document is used for the American Quarter Horse Association transfers, and BIDDER’S NUMBER invoicing. A paid receipt or release is required to remove any horse from the sale IS REQUIRED grounds. Please register with cashiers Present the PINK copy of the sales receipt to a sales security officer. prior to bidding. DO NOT REMOVE HIP NUMBERS from horses before leaving the Driver’s license or valid photo I.D. sale grounds. required when bidding. ALL SALES OR TRANSACTIONS FOR HORSES ENTERED IN THIS SALE ARE AS/IS. BIDDER’S NUMBER AND PAYMENT Announcements: To avoid making costly errors, please pay attention Buyers MUST register for a Bidder’s Number. to all announcements made from the sales office and the auction PLEASE REGISTER WITH CASHIER PRIOR TO BIDDING. stand, especially concerning horses on which you intend to bid. Special announcements made concerning individual hip numbers To register you will need to present: will appear on the tote board. (1) Picture identification such as a driver’s license. (2) Provide payment and bank information. Please listen carefully to announcements made at the time the horse (3) Buyers paying with personal or business checks MUST is sold. -

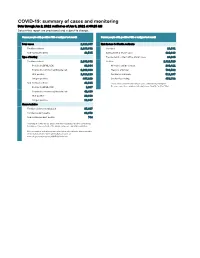

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Jan 14, 2021 Verified As of Jan 15, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Jan 14, 2021 verified as of Jan 15, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,548,067 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,519,944 Florida residents 1,519,944 Traveled 12,636 Non-Florida residents 28,123 Contact with a known case 567,469 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 17,180 Florida residents 1,519,944 Neither 922,659 Positive by BPHL/CDC 55,093 No travel and no contact 174,637 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,464,851 Travel is unknown 549,595 PCR positive 1,271,326 Contact is unknown 335,058 Antigen positive 248,618 Contact is pending 360,747 Non-Florida residents 28,123 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 728 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 27,395 PCR positive 20,231 Antigen positive 7,892 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 67,463 Florida resident deaths 23,799 Non-Florida resident deaths 370 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

PINE CREEK WATERSHED CHANNEL and RIPARIAN ASSESSMENT and RESTORATION PLAN

PINE CREEK WATERSHED CHANNEL and RIPARIAN ASSESSMENT and RESTORATION PLAN NORTH AREA ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL in partnership with the PINE CREEK WATERSHED COALITION ALLEGHENY COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA March 2010 Pine Creek Watershed Riparian and Stream Channel Assessment Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Background 3 3. Watershed Description 4 3.0 Watershed Map 4 3.1 Physical Description 6 3.2 Physiographic Setting and Geology 7 3.3 Important Natural Areas 9 3.4 Development 10 4. Visual Assessment Description 11 5. Pine Creek Stream Segment Analysis with Restoration Recommendations 13 5.0 a) Image of all waypoints studied 14 b) Pine Creek Reach Map – Color Coded 15 5.1 Main Pine Creek Section 4 16 5.2 Main Pine Creek Section 3 21 5.3 Main Pine Creek Sections 1 and 2 26 5.4 North Fork Pine Creek 31 5.5 Montour Run 35 5.6 Willow Run 39 5.7 Crouse Run 44 5.8 McCaslin Run 48 5.9 Gourdhead Run 51 5.10 Harts Run 55 5.11 East Little Pine Creek 58 5.12 West Little Pine Creek 61 6. Conclusions and Recommendations 67 6.0 a) Map of recommended project sites and introduction 67 6.1 Erosion 68 6.2 Debris Jams 69 6.3 Riparian Zone Encroachment 69 6.4 Illegal Dumping and Debris 70 6.5 Sedimentation 70 6.6 Exotic invasive plants 70 6.7 Restoration Priorities 71 7. Attachments 72 7.0 Attachments 72 7.1 USDA Protocol 72 7.2 Rosgen Protocol 72 7.3 Visual Assessment Score Sheet 73 7.4 Walks In The Watershed 83 7.5 Data Description and Ways to Use the Data 88 7.6 PCRA Blank Field Data Summary Degrees and Decimal Minutes.XLS 104 7.7 Google Earth KMZ File 104 Report revised 03/30/2010 - 2 - Pine Creek Watershed Riparian and Stream Channel Assessment 1.0 INTRODUCTION Pine Creek watershed is a “high priority” watershed in northern Allegheny County encompassing 67.3 square miles and part or all of 14 municipalities. -

U.S. Industrial Garnet Industrial U.S

U.S. Industrial Garnet Chapter L of Contributions to Industrial-Minerals Research Evans and Moyle—U.S. Industrial Garnet—U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2209–L Bulletin 2209–L U.S. Department of the Interior Printed on recycled paper U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Industrial Garnet By James G. Evans and Phillip R. Moyle Chapter L of Contributions to Industrial-Minerals Research James D. Bliss, Phillip R. Moyle, and Keith R. Long, Editors Bulletin 2209–L U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior P. Lynn Scarlett, Acting Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 This report and any updates to it are available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/b2209-l/ For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1–888–ASK–USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1–888–ASK–USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Cataloging-in-Publication data are on file with the Library of Congress (URL http://www.loc.gov/). Produced in the Western Region, Menlo Park, California Manuscript approved for publication, March 29, 2006 Text edited by George A. -

What's Happening in December? INSTITUTION Connecticut State Migratory Children's Program, New Haven.; Hamden-New Haven Cooperative Education Center, Conn

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 225 726 RC 013 766 AUTHOR Pla, Myrna; Toro, Leonor TITLE What's Happening in December? INSTITUTION Connecticut State Migratory Children's Program, New Haven.; Hamden-New Haven Cooperative Education Center, Conn. SPONS AGENCY Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (ED), Washington, DC. Migrant Education Programs. PO DATE Dec 82 NOTE, 80p.; For related documents, see RC 013 764-765 and ED 212 394. Best copy available. AVAILABLE FROMEthnic/Arts Migrant Project, Hamden-New Haven Cooperative Education Center, 1450 Whitney Avenue, Hamden, CT 06517-2497. P-JB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICES MFO1/IT04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Activities; Cultural Awareness; Cultural Education; Elementary Education; Folk Culture; Illustrations; *Language Arts; *Learning Activities; *Migrant Education; Poetry; Puerto Rican Culture; *Puerto Ricans; Short Stories IDENTIFIERS Christmas; Connecticut; Holidays; *Recipes (Food); Winter ABSTRACT Part of a series of monthly booklets designed as a teacher resource for teaching about Puerto Rican and U.S.culture, the booklet provides brief information on twoDecember events: winter and ChristMas. Brief information is provided onwinter, Hanukkah, Christmas traditions in Connecticut and in Puerto Rico, andChristmas symbols (the tree, carols, poinsettias, cards, and SantaClaus). The booklet includesthe words to nine poems--"Cold Winter Now Isin the Wood," ttChristmas in the City," "Mrs. Santa Claus,""Christmas Is Coming," "This Is the Way That Christmas -

Vegan Travel Guide by Eh Vegan

V E G A N T R A V E L G U I D E eh vegan l o s a n g e l e s , c a l i f o r n i a eh vegan YOUR VEGAN GUIDE TO LA vegan eats 3 see & do 10 getting around 11 where to stay 12 shopping 13 festivals & events 14 sanctuaries 15 community 16 Los Angeles — the City of Angels, sandy beaches, movie stars, and a seemingly endless choice of vegan restaurants. Known for a culture of good vibes, you’ll find yourself in like-minded company among the cities' many vegan residents. The attitude towards veganism will feel like a breath of fresh air and have you wanting to visit again and again. V E G A N T R A V E L G U I D E | L O S A N G E L E S P A G E 2 the don't miss list eh vegan Unless you’re planning to stay a month, you probably won’t have time to try it all. LA has a lot to offer — more than most cities. Between the scenic views from Mulholland Drive to the breezy air on the Santa Monica Pier, there are plenty of sights that shouldn’t be missed. But this is about food, so when you’re ready to eat, here are the restaurants that should be at the top of your list. @crossroadskitchen Crossroads Sun Cafe Donut Friend Crossroads is the best Sun Café is the star of Donut Friend is the build- upscale vegan food you'll Studio City. -

2021-02-02 010515__2021 Stocking Schedule All.Pdf

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2021 Trout Stocking Schedule (as of 2/1/2021, visit fishandboat.com/stocking for changes) County Water Sec Stocking Date BRK BRO RB GD Meeting Place Mtg Time Upper Limit Lower Limit Adams Bermudian Creek 2 4/6/2021 X X Fairfield PO - SR 116 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 2 3/15/2021 X X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 4 3/15/2021 X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 GREENBRIAR ROAD BRIDGE (T-619) SR 94 BRIDGE (SR0094) Adams Conewago Creek 3 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 3 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 4 4/22/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 10/6/2021 X X Letterkenny Reservoir 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 5 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. -

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Jun 2, 2021 Verified As of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Jun 2, 2021 verified as of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,329,867 Risk factors for Florida residents 2,286,332 Florida residents 2,286,332 Traveled 18,931 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Contact with a known case 920,896 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 24,985 Florida residents 2,286,332 Neither 1,321,520 Positive by BPHL/CDC 83,364 No travel and no contact 280,411 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 2,202,968 Travel is unknown 733,532 PCR positive 1,819,119 Contact is unknown 511,267 Antigen positive 467,213 Contact is pending 459,732 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 1,037 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 42,498 PCR positive 29,688 Antigen positive 13,847 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 95,607 Florida resident deaths 36,973 Non-Florida resident deaths 744 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

Danny Avila Contrast and Tujamo *

561 DRUM & BASS SPECIAL! 27-PAGES OF JUNGLIST GOODNESS! DJMAG.COM WHALE OF A TIME MOBY’S NEW BOOK TEKLIFE LIVING & BREATHING DANCE MUSIC! CREW DJMAG.COM LIVE ON DJ RASHAD’S FOOTWORK LEGACY THE CONTINUED WIDESCREEN ELI ESCOBAR DRUM & BASS OF IN PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS * MUSIC DOWNLOAD * CLUBS CONTENT BY HIGH JEWELZ & SPARKS, * TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY DANNY AVILA CONTRAST AND TUJAMO * HAS D&B COMMERCIALISATION GONE TOO FAR? SIGMA, GOLDIE, GROOVERIDER, FRICTION & MORE EXPLORE VOTE NOW! HOSPITALITY IN THE PARK UK’S FIRST D&B FEST D&B IN AMERICA — F*** YEAH! ALL THE No. 561 NOMINEES EXIT RECORDS PROFILED September 2016 TRUE TO THE CRAFT WE CZECH OUT No.561 September 2016 £4.95 LET IT ROLL & BEATS EVOLUTION £4.95 OCTAVE ONE, MACHINEDRUM, HERVÉ, THOMAS GANDEY, BLACK DEVIL DISCO CLUB, PLUS: FELIX DICKINSON, RECLOOSE, REBOOT, DE SLUWE VOS, SECRET CINEMA, SILKY… cover1.indd 1 12/08/2016 14:00 Untitled-1 1 18/07/2016 12:16 Contents Cover Shot: LARRY ROSTANT 032 WIDESCREEN DRUM & BASS High Contrast’s cinematic productions have made him the undisputed master of underground-credible yet mainstream-accessible d&b. DJ Mag heads to Cardiff to meet the man behind the music... FEATURES 038 COMMERCIAL PROPERTIES Following Sigma’s collab with Take That, we ask industry heavyweights to way up the pros and cons of commercial d&b 046 NON-CORPORATE HOSPITALITY Label heads London Elektricity and Chris Goss talk 20 years of Hospital Records 038 COMMERCIAL D&B 051 EXIT RECORDS and the UK’s fi rst ever d&b festival... 051 BOW DOWN TO THE EXIT We sit down with Exit Records boss dBridge to see why his boundary- breaking imprint stays true to the craft..