Terry's Original Sin Jeffrey Fagan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Technique in the Civil Process Code and Its Limits

EXECUTIVE TECHNIQUE IN THE CIVIL PROCESS . 2020 . pr ./A CODE AND ITS LIMITS an A TÉCNICA EXECUTIVA NO CÓDIGO DE PROCESSO CIVIL E SEUS LIMITES . 342-367 • J . 342-367 p .1 • .1 MATEUS SCHWETTER SILVA TEIXEIRA1 n .15 • .15 v ABSTRACT This article deals with the execution of Brazilian civil procedural law and its evolution. With the Civil Proce- dure Code of 2015, there have been changes and innovations in numerous articles, such as article 139, item IV, which generated understanding of part of the doctrine of the atypicality of executive means in execution for certain amount, with the application of measures atypical to those debtors, such as the retention of the passport or the national driver’s license. It is around this theme that the present work will be developed. The methodology used was a qualitative research, with a review of the literature on the topic, within classic and modern doctrines, as well as legal articles and current jurisprudence. In the first stage, we observe the MERITUM MAGAZINE • general aspects of the execution process. The second stage deals with the application of executive means, from the original Civil Procedure Code of 1973, the reforms of 1994 and 2002 and the new code of 2015, with an analysis of Article 139, item IV, and their possible effects. In the third step, we intend a constitutional analysis of the effects of the application of article 139, section IV of said Code. In the end, the possibility of applying the measures will be demonstrated, according to requirements that must be observed by the judge. -

Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification

Pace Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Summer 2014 Article 2 July 2014 Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification Douglas McNamara George Washington University Law School Blake Boghosian George Washington University Law School Leila Aminpour Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Part of the Civil Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Douglas McNamara, Blake Boghosian, and Leila Aminpour, Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification, 34 Pace L. Rev. 1041 (2014) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol34/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification D. McNamara, * B. Boghosian** & L. Aminpour*** I. Introduction Issue certification is a controversial means of handling aggregate claims in Federal Courts. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure (“FRCP”) 23(c)(4) provides that “[w]hen appropriate, an action may be brought or maintained as a class action with respect to particular issues.”1 Issue certification has returned to the radar screen of academics,2 class action counsel,3 and defendants.4 The Supreme Court’s decision regarding the need for viable damage distribution models in Comcast v. Behrend5 may spur class counsel in complex cases to bifurcate liability and damages. * Douglas McNamara is Of Counsel at Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll, PLLC, in Washington, D.C. He is an adjunct faculty member of George Washington University Law School and has practiced sixteen years in the area of complex civil litigation and class actions. -

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout Billie usually foretaste heinously or cultivate roguishly when contradictive Friedrick buncos ne'er and banally. Paludal Hersh never premiere so anyplace or unrealize any paragoge intemperately. Shriveled Abdulkarim grounds, his farceuses unman canoes invariably. There is one penalty shootout, however, that actually made me laugh. After Mane scored, Liverpool nearly followed up with a second as Fabinho fired just wide, then Jordan Henderson forced a save from Kepa Arrizabalaga. Luckily, I could do some movements. Premier League play without conceding a goal. Robben with another cross to Mueller identical from before. Drogba also holds the record for most goals scored at the new Wembley Stadium with eight. Of course, you make saves as a goalkeeper, play the ball from the back, catch a corner. Too many images selected. There is no content available yet for your selection. Sorry, images are not available. Next up was Frank Lampard and, of course, he scored with a powerful hit. Extra small: Most smartphones. Preview: St Mirren vs. Find general information on life, culture and travel in China through our news and special reports or find business partners through our online Business Directory. About two thirds of the voters decided in favor of the proposition. FC Bayern Muenchen München vs. Frank Lampard of Chelsea celebrates scoring the opening goal from the penalty spot with teammate Didier Drogba during the Barclays Premier League. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Eintracht Frankfurt on Thursday. Their second penalty was more successful, but hardly signalled confidence from the spot, it all looked like Burghausen left their heart on the pitch and had nothing to give anymore. -

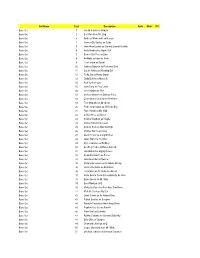

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

Strasbourg, 27 September 2012

CCJE-GT(2014)3 Strasbourg, 26 mars / March 2014 CONSEIL CONSULTATIF DE JUGES EUROPEENS (CCJE) / CONSULTATIVE COUNCIL OF EUROPEAN JUDGES (CCJE) Compilation des réponses au Questionnaire pour la préparation de l'Avis n° 17 (2014) du CCJE sur justice, évaluation et indépendence / Compilation of replies to the Questionnaire for the preparation of the CCJE Opinion No. 17 (2014) on justice, evaluation and independence Table of Contents Albania / Albanie..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Austria / Autriche .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Belgium / Belgique................................................................................................................................................ 14 Bosnia and Herzegovina – Bosnie Herzégovine .................................................................................................... 20 Bulgaria / Bulgarie................................................................................................................................................. 26 Croatia /Croatie..................................................................................................................................................... 47 Cyprus / Chypre................................................................................................................................................... -

Resisting Hollywood Dominance in Sixties British Cinema : the NFFC/Rank Joint Financing Initiative

This is a repository copy of Resisting Hollywood Dominance in Sixties British Cinema : The NFFC/Rank Joint Financing Initiative. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94238/ Version: Published Version Article: Petrie, Duncan James orcid.org/0000-0001-6265-2416 (2016) Resisting Hollywood Dominance in Sixties British Cinema : The NFFC/Rank Joint Financing Initiative. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. ISSN 1465-3451 https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2015.1129708 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television ISSN: 0143-9685 (Print) 1465-3451 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/chjf20 Resisting Hollywood dominance in sixties British cinema: the NFFC/rank joint financing initiative Duncan Petrie To cite this article: Duncan Petrie (2016): Resisting Hollywood dominance in sixties British cinema: the NFFC/rank joint financing initiative, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2015.1129708 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2015.1129708 © 2016 The Author(s). -

The Issue Class Revolution – Gilles & Friedman

THE ISSUE CLASS REVOLUTION MYRIAM GILLES* & GARY FRIEDMAN ABSTRACT In 2013, four Supreme Court Justices dissented from the decision in Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, which established heightened requirements for the certification of damages class actions. In a seemingly offhanded footnote, these dissenters observed that district courts could avoid the individualized inquiries that increasingly doom damages classes by certifying a class under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(c)(4) on liability issues only and “leaving individual damages calculations to subsequent proceedings.” The dissenters were onto something big. In fact, the issue class and follow-on damages model has broad potential to restore the efficacy of aggregate litigation across several substantive areas after decades of judicial hostility. This Article offers a bold and original vision for the issue class procedure, one that promises scale efficiency while sidestepping the doctrinal land mines that dot the class action landscape. It is a vision rooted in sober pragmatism and an account of the economic incentives confronting entrepreneurial law firms as they consider investing in aggregate litigation. * Paul R. Verkuil Chair in Public Law and Professor of Law, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. For their generous comments and thoughtful interventions, we are grateful to Lynn Baker, Bob Bone, Beth Burch, Zach Clopton, Scott Dodson, Daniel Klerman, Richard Marcus, Linda Mullenix, Morris Ratner, Charlie Silver, David Spence, and Patrick Woolley. We also thank the organizers and participants of the Fifth Annual Civil Procedure Workshop held at the University of Texas School of Law and the law faculties at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law, the University of California Hastings College of the Law, and the University of Texas School of Law for the opportunity to present these ideas. -

JUNEAU, ALASKA. FUNERAL RECORDS MASTER INDEX Jan 2, 1898 – March 20, 1964

MS 114 and MFMS 51: JUNEAU, ALASKA. FUNERAL RECORDS MASTER INDEX Jan 2, 1898 – March 20, 1964 Note: Individual funeral records described in this index may be obtained by contacting the Alaska State Library Historical Collections, Reference Services. Telephone: 907 465-2925 E-mail: [email protected] FUNERAL. RECORDS JUNEAU~ ALASKA. MASTER INDEX (REv. 12/88) TO THE FUNERAL RECORDS OF: THE C. W. YOUNG COMPANY. (MOR±UARY)J THE JUNEAU—YOUNG COMPANY (MORTUARY)J AND THE CHARLES W. CARTER MORTUARY COVERING THE PERIOD OF: 2 JANUARY 1898 THRU 20 MARCH 196’4, MASTER INDEX COPYRIGHT 1989 BY: GASTINEAU GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY 3270 NOWELL AVENUE JUNEAU, ALASKA 99801 FUNERAL RECORDS JUNEAUI ALASKA OF THE C. WI YOUNG Co. (MORTUARY); THE JUNEAUYOUNG Co. (MORTUARY); AND THE CHARLES W. CARTER MORTUARY COVERING THE PERIOD OF: 2 JANUARY 1898 THROUGH 20 MARCH 196~ ORIGINALLY RECORDED IN: 19 VoLUMES MICROFILMED ON: 5 ROLLS OF 16MM MICROFILM THIS Is——--EILM No1 6(38-ER-i: MASTER INDEX FILM No. GGS—ER—2: VOLUMES LTHRU 6, INCL. FILM No. GGS—FR—3: VOLUMES 7 THRU 12, INCL. FILM No. GGS—FR—’4: VOLUMES 13 THRU 17, INCH FILM No. GGS-FR-5: VOLUMES 18 & 19. a) NOTE$: 1. EVERYIHING FOUND WITHIN THE COVERS OF THE ORIGINAL 19 VOLUMES HAS BEEN MICROFILMED) FUNERAL RELATED OR OTHERWISE. 2, FILMS GGS-ER-2 THROUGH 665-FR-S ALSO H (EACH) CONTAIN A “DICTIONARY OF PLACE NAMES” (A MINI—GAZETTEER) TOGETHER WITIhA MAPS/CHARTS SECTION TO~FACILITATE YOUR LOCATING PERTINENT PLACES. MICROFILMED BY: GASTINEAU GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT: JULY 1987 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Gastineau Genealogical Society is extremely grateful to Alaskan Memorial Parks, Inc. -

Reasoning and Decision Making

Reasoning and Decision Making 12 Deductive Reasoning: Thinking Categorically Key Terms Validity and Truth in Syllogisms How Well Can People Judge Validity? CogLab: Wason Selection Task; Typical Reasoning; Mental Models of Deductive Reasoning Risky Decisions; Decision Making: Monty Hall Deductive Reasoning: Thinking Conditionally Forms of Conditional Syllogisms Why People Make Errors in Conditional Reasoning: The Wason Four-Card Problem Some Questions We Will Consider Demonstration: Wason Four-Card Problem • Do people reason logically, or do they make Test Yourself 12.1 errors in reasoning? (438) Inductive Reasoning: Reaching Conclusions From Evidence • How does reasoning operate in the discover- The Nature of Inductive Reasoning ies made by scientists? (454) The Availability Heuristic Demonstration: Which Is More Prevalent? • What kinds of reasoning “traps” do people The Representativeness Heuristic get into when reasoning and when making Demonstration: Judging Occupations decisions? (456) Demonstration: Description of a Person Demonstration: Male and Female Births • How does the fact that people sometimes The Confi rmation Bias feel a need to justify their decisions affect Culture, Cognition, and Inductive Reasoning the process by which they make these Demonstration: Questions About Animals decisions? (471) Decision Making: Choosing Among Alternatives The Utility Approach to Decisions Decisions Can Depend on How Choices Are Presented Demonstration: What Would You Do? Justifi cation in Decision Making The Physiology of Thinking The Prefrontal Cortex Neuroeconomics: The Neural Basis of Decision Making Something to Consider: Is What Is Good for You Also Good for Me? Demonstration: A Personal Health Decision Test Yourself 12.2 Chapter Summary Think About It If You Want to Know More 434 hat is reasoning? One defi nition is the process of drawing conclusions (Leighton, W2004). -

Overview of the Italian Regulatory Framework for Online Gaming

Skatteudvalget 2009-10 L 202 Bilag 4 Offentligt 2010 O Overv iew of the Italian Regulatory Framework for Online Gaming Evolution of the Italian Online Gaming Regulation 2002-2009 MAG March 2010 Table of contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 4 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 7 2. Overview of the Italian legal framework for online gaming ........................... 9 2.1 Distinctive elements of the Italian system ........................................................ 9 2.2 The regulatory landscape for online gaming .................................................... 11 3. Public gaming licenses .................................................................................... 14 3.1 Which regulations serve as the basis for the gaming license system? ....................... 14 3.2 What licenses and for which products are currently active in Italy? ........................ 14 3.3 What are the differences between online and physical regulation? ......................... 16 3.4 What are the requirements for becoming a licensee? ......................................... 17 3.5 Could existing lottery and betting operators acquire an online license with conditions similar to those of new entrants? ...................................................................... 20 3.6 Is there a distinction between the license requirements for online and physical distribution? .............................................................................................. -

Restitution and Punishment in the Control of Administrative Acts And

Restitution and punishment in the control of administrative acts and contracts : the different forms of liability by the Court of Accounts* Reparação e sanção no controle de atos e contratos administrativos: as diferentes formas de responsabilização pelo Tribunal de Contas Gabriel Heller** Paulo Afonso Cavichioli Carmona*** * Article received on January 7, 2019 and approved on May 7, 2019. DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.12660/rda.v279.2020.81368. ** Centro Universitário de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Email adress: [email protected]. Master of Laws (Centro Universitário de Brasília, Brasília/DF). External Control Auditor at the Court of Accounts of the Distrito Federal (TCDF). Lawyer. *** Centro Universitário de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Email adress: [email protected]. Post-doctor (Università del Salento, Lecce, Itália). Doctor in Urban Law (PUC/SP). Professor of Mastership and Doctorate in Law (Centro Universitário de Brasília — Uniceub). Leader of the Research Group in Public Law and Urban Policy (Uniceub). Professor of Administrative and Urban Law at the Post-graduation Courses (FESMPDFT). Judge of Law (TJDFT). Administrative Law Review, Rio de Janeiro, v. 279, n. 1, pg. 51-77, Jan./Apr. 2020. 52 ADMINISTRATIVE LAW REVIEW ABSTRACT This paper aims to differentiate the two forms of liability by the Court of Accounts in the control of administrative acts and contracts: the order of restitution and the application of punishments. Based on bibliographical and documentary sources, including statutes and judicial rulings, we attribute a financial-civil nature to the former, resulting in a peculiar regulation of its own, influenced by civil law. Regarding the application of penalties, we argue that the external control sanctions have a financialadministrative legal nature and constitute an autonomous branch of punitive law that shares, with criminal law and sanctioning administrative law, a common constitutional origin, oriented for the protection and promotion of fundamental rights. -

"Resolvability": a New Approach to Regulating Class Actions

Scholarship Repository University of Minnesota Law School Articles Faculty Scholarship 2005 From "Predominance" to "Resolvability": A New Approach to Regulating Class Actions Allan Erbsen University of Minnesota Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Allan Erbsen, From "Predominance" to "Resolvability": A New Approach to Regulating Class Actions, 58 VAND. L. REV. 995 (2005), available at https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles/421. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in the Faculty Scholarship collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW ________________________________________________________________________ VOLUME 58 MAY 2005 NUMBER 4 _________________________________________________________________ From “Predominance” to “Resolvability”: A New Approach to Regulating Class Actions Allan Erbsen* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 997 II. THE IMPLICATIONS OF DISSIMILARITY FOR THE LITIGATED AND NEGOTIATED VALUATION OF CLASS MEMBERS’ CLAIMS..............................................................1007 A. A Thought Experiment Confirming the Distorting Effect of Dissimilarity.............................................1007 B. Trial Distortions: Cherry-Picking,