Correcting Recent Bodie Myths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Settlement of the West

Settlement of the West The Western Career of Wild Bill Hickok James Butler Hickok was born in Troy Grove, Illinois on 27 May 1837, the fourth of six children born to William and Polly Butler Hickok. Like his father, Wild Bill was a supporter of abolition. He often helped his father in the risky business of running their "station" on the Underground Railroad. He learned his shooting skills protecting the farm with his father from slave catchers. Hickok was a good shot from a very young age, especially an outstanding marksman with a pistol. He went west in 1857, first trying his hand at farming in Kansas. The next year he was elected constable. In 1859, he got a job with the Pony Express Company. Later that year he was badly mauled by a bear. On 12 July 1861, still convalescing from his injuries at an express station in Nebraska, he got into a disagreement with Dave McCanles over business and a shared woman, Sarah Shull. McCanles "called out" Wild Bill from the Station House. Wild Bill emerged onto the street, immediately drew one of his .36 caliber revolvers, and at a 75 yard distance, fired a single shot into McCanlesʼ chest, killing him instantly. Hickok was tried for the killing but judged to have acted in self-defense. The McCanles incident propelled Hickock to fame as a gunslinger. By the time he was a scout for the Union Army during the Civil War, his reputation with a gun was already well known. Sometime during his Army days, he backed down a lynch mob, and a woman shouted, "Good for you, Wild Bill!" It was a name which has stuck for all eternity. -

University of Nevada, Reno Cultural Landscape Development And

University of Nevada, Reno Cultural Landscape Development and Tourism in Historic Mining Towns of the Western United States A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geography By Alison L. Hotten Dr. Gary J. Hausladen/Thesis Advisor May, 2011 © Copyrighted by Alison L. Hotten 2011 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by ALISON L. HOTTEN entitled Cultural Landscape Development And Tourism In Historic Mining Towns Of The Western United States be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Gary J. Hausladen, Ph.D., Advisor Paul F. Starrs, Ph.D., Committee Member Alicia Barber, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2011 i Abstract This thesis examines the development of the cultural landscape of western mining towns following the transition from an economy based on mining to one based on tourism. The primary case studies are Bodie, California, Virginia City, Nevada, and Cripple Creek, Colorado. Each one is an example of highly successful tourism that has developed in a historic mining town, as well as illustrating changes in the cultural landscape related to this tourism. The main themes that these three case studies represent, respectively, are the ghost town, the standard western tourist attraction, and the gambling mecca. The development of the landscape for tourism is not just commercial, but relates to the preservation of history and authenticity in the landscape; each town was designated as a Historic District in 1961. -

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index Revised and edited by Kristina L. Southwell Associates of the Western History Collections Norman, Oklahoma 2001 Boxes 104 through 121 of this collection are available online at the University of Oklahoma Libraries website. THE COVER Michelle Corona-Allen of the University of Oklahoma Communication Services designed the cover of this book. The three photographs feature images closely associated with Walter Stanley Campbell and his research on Native American history and culture. From left to right, the first photograph shows a ledger drawing by Sioux chief White Bull that depicts him capturing two horses from a camp in 1876. The second image is of Walter Stanley Campbell talking with White Bull in the early 1930s. Campbell’s oral interviews of prominent Indians during 1928-1932 formed the basis of some of his most respected books on Indian history. The third photograph is of another White Bull ledger drawing in which he is shown taking horses from General Terry’s advancing column at the Little Big Horn River, Montana, 1876. Of this act, White Bull stated, “This made my name known, taken from those coming below, soldiers and Crows were camped there.” Available from University of Oklahoma Western History Collections 630 Parrington Oval, Room 452 Norman, Oklahoma 73019 No state-appropriated funds were used to publish this guide. It was published entirely with funds provided by the Associates of the Western History Collections and other private donors. The Associates of the Western History Collections is a support group dedicated to helping the Western History Collections maintain its national and international reputation for research excellence. -

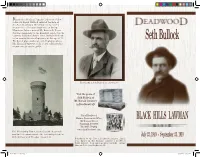

Seth Bullock Mt

Roosevelt’s death in January 1919 was a blow to his old friend. Bullock enlisted the help of the Society of Black Hills Pioneers to erect a monument to Theodore Roosevelt on Sheep Mountain, later renamed Mt. Roosevelt. It was the first monument to the president erected in the country, dedicated July 4, 1919. Bullock died just a few months later in September at the age of 70. His burial plot resides on a small plateau above Seth Bullock Mt. Moriah Cemetery, with a view of Roosevelt’s monument across the gulch. Photograph of Seth Bullock circa 1890-1900. Visit the grave of Seth Bullock at Mt. Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood, SD City of Deadwood Historic Preservation Office BLACK HILLS LAWMAN 108 Sherman Street Deadwood, SD 57732 Tel.: (605) 578-2082 www.cityofdeadwood.com The Friendship Tower, located on Mt. Roosevelt, was built to commemorate the friendship between Seth Bullock and Theodore Roosevelt. July 23, 1849 - September 23, 1919 Reproduced by the City of Deadwood Archives, March 2013. Images in this brochure courtesy of Deadwood Public Library - Centennial Archives and DHI - Adams Museum Collection, Deadwood, SD EDIT_SEth_01_2013.indd 1 3/15/2013 1:38:57 PM Seth Bullock and Sol Star posing on the 1849 - Seth Bullock - 1919 Redwater Bridge circa 1880s. The quintessential pioneer and settler of the preserve that magnificent land, protecting it he Bullocks were founders of the Round Table American frontier has to be Seth Bullock who, from settlement. His resolution was adopted and T Club, the oldest surviving cultural club in the ironically, was born in Canada. -

Wild West Canada: Buffalo Bill and Transborder History

Wild West Canada: Buffalo Bill and Transborder History A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon Adam Grieve Copyright Adam Grieve, April, 2016. All Rights Reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Abstract Canadians continue to struggle with their western identity. For one reason or another, they have separated themselves from an Americanized “blood and thunder” history. -

Wild West.” – the Omaha Daily Bee, May 21, 1883

The Wild West Keeping the American Legend Alive By Elizabeth Mack For a month past the great event to which all our citizens were looking forward was the appearance of the Cody and Carver combination, with their original and novel Nebraska show, entitled the “Wild West.” – The Omaha Daily Bee, May 21, 1883 he newspaper excerpt above public’s imagination. What was, and way to satisfy the public’s fascination describes the first ever Wild continues to be, the attraction to these with the West. Even as early as the West exhibition of William shows and the Wild West? late 1880s, Cody and others believed F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Cody’s “The Wild West, Rocky the West was dying, and that his performed in Omaha to an Mountain, exhibitions were a way to keep it alive. Tenthusiastic crowd. Along with Codyody aandnd AAccordingccord to Sarah Blackstone, author was his one-time partner, Doc Carver,ver, ooff BuBuckskins,ck Bullets and Business, and their large troupe of performers,rs, by the ttime Cody’s shows were at the including Capt. A.H. Bogardus (U.S..S. hheighteight oof their popularity in the early champion trap shooter), as well as 18901890s,s “all but four of the Western numerous Pony Express riders tterritorieserri had become states, the and Sioux, Omaha and Pawnee lalastst Indian uprising had been Indians (Chief Sitting Bull and ququelled, and there were four Annie Oakley would later join trtranscontinental railroads.” the troupe) and even a small SSettlers were coming west by herd of buffalo. The newspaper the thousands, and for Buffalo reported “no less than 8,000 Bill, these exhibitions served persons were present to witness to not only entertain, but to the opening” of Cody’s quell what was becoming extravaganza, a substantial known as “frontier anxiety.” number even by today’s Many Americans became standards. -

“Calamity Jane” Canary - 1903 Mayo Pose in Front of Wild Bill’S Grave at Mt

Travel Through History 1856, May 1 - Martha Canary is born in Mercer County near the town of Princeton, Missouri. She was to become the eldest of six siblings. 1865 - Martha moves with her family to Virginia City, Montana Territory. 1866, spring - Martha’s mother, (Charlotte M. Canary) dies in Blackfoot City mining camp, Montana Territory. 1867 - Martha’s father (Robert Willson Canary) dies in Utah orphaning the Canary children. Martha Canary 1868 - Martha arrives in the Wyoming Territory and begins exploration within the area. 1873 - Captain James Egan allegedly christens Martha Canary with the nickname “Calamity Jane” after she saved his life during an Indian campaign at Goose Creek, Wyoming. 1875, May-June - Newton and Jenney Expedition leaves Ft. Laramie to the Black Hills. Calamity Jane accompanied expedition without proper authority and was forced to return. 1875, fall - Gold discovered in Whitewood Creek and adjacent tributaries. 1876, June - Calamity Jane leaves Ft. Laramie and heads for Portrait of Martha Canary circa 1880-1882 while she was living in the Black Hills with many famous Deadwood legends, including Miles City, Montana Territory. James Butler Hickok, Colorado Charlie Utter, and White-Eyed Anderson. 1876, August 2 - Wild Bill Hickok is murdered by Jack McCall in the No. 10 Saloon. Visit the grave of 1878 - Calamity Jane nurses many people when the small pox Calamity Jane epidemic hits the Black Hills. at Mt. Moriah Cemetery in 1879 - Jane works as a bullwhacker, driving teams between Deadwood, South Dakota Pierre, Fort Pierre, and Rapid City, Dakota Territory. 1891 - Calamity Jane marries Clinton Burke (Burk), a hack driver in El Paso, Texas. -

Letter Reso 1..3

*LRB09612565GRL25812r* HR0360 LRB096 12565 GRL 25812 r 1 HOUSE RESOLUTION 2 WHEREAS, James Butler Hickok, better known as Wild Bill 3 Hickok, was born in Homer (now Troy Grove) on May 27, 1837; 4 while he was growing up, his father's farm was one of the stops 5 on the Underground Railroad, and he learned his shooting skills 6 protecting the farm with his father from slave catchers; and 7 WHEREAS, In 1855, at the age of 18, Wild Bill Hickok moved 8 to the Kansas Territory; while in Kansas, he joined General Jim 9 Lane's vigilante Free State Army; at the age of 21, Hickok was 10 elected constable of Monticello Township; and 11 WHEREAS, When the Civil War began, Wild Bill Hickok joined 12 the Union forces and served in the west, mostly in Kansas and 13 Missouri, and earned a reputation as a skilled scout; after the 14 war, he became a scout for the United States Army and served 15 for a time as a United States Marshal; he also engaged in 16 buffalo hunting with Buffalo Bill Cody, Robert Denbow, and 17 David L. Payne; and 18 WHEREAS, In 1870, Wild Bill Hickok served as sheriff of 19 Hays, Kansas; in 1873, Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack 20 Omohundro invited Hickok to join them in a new play called 21 Scouts of the Plains after their earlier success; Hickok 22 eventually left the show before Cody formed his Buffalo Bill's -2-HR0360LRB096 12565 GRL 25812 r 1 Wild West Show in 1882; and 2 WHEREAS, Wild Bill Hickok quickly developed a reputation as 3 a feared gunfighter; on July 21, 1865, in the town square of 4 Springfield, Missouri, Hickok killed Davis Tutt, Jr. -

It's Time to Check out Our Online Collections

P INTSWESTfall/winter 2014 It’s Time To Check Out Our Online Collections ■ Rough riding the Wild West ■ Hickok et. al: How good were they? ■ Traveling West page by page About the cover: P INTSWESTfall/winter 2014 It’s Time To Check Out Our Pocket watches Online Collections ■ Rough riding the Wild West ■ from the Center’s Hickok et. al: How good were they? to the point ■ Traveling West page by page collection. (Details on back cover.) Learn BY BRUCE ELDREDGE | Executive Director about the Center’s online collection and more on pages 4 - 9. ©2014 Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Points West is published for members and friends of the Center of the West. Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are Center of the West photos unless otherwise noted. Direct all questions about image rights and reproduction to [email protected]. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve space. However, such information is available by contacting the editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or [email protected]. “Yes, keeping up with it all is a tall order.” ■ Managing Editor | Marguerite House – bruce eldredge ■ Assistant Editor | Nancy McClure ■ Designer | Desirée Pettet f you’re like me, today’s technology leaves us baffled. Websites, social ■ Contributing Staff Photographers | Nancy media, e-newsletters, cell phones, and everything in between, are simply so McClure and Ken Blackbird for the Center big, it’s hard to grasp how they all fit together. -

"I Know.. . Because I Was There": Leander P. Richardson Reports the Black Hills Gold Rush

Copyright © 2001 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. "I Know.. because I Was There": Leander P. Richardson Reports the Black Hills Gold Rush James D. McLaird Wlien in 1894 a Mr. Adler claimed in an article for tlie Deruer Republican diat he had witnessed die murder of James Buder ("Wild BiL") Hickok in 187Ó, newspaperman Leander P. Richardson called him a liar. In his article, Adler claimed Hickok to be an expert gam- bler and a partner of Jack McCall, w^ho, after a disagreement, mur- dered Wild Bñl while he played cards. According to Adler, Hickok fell face first into the poker chips when shot. In contradiction, Ricli- arcLson contended diat there were no poker chips at the table when Hickok was killed, nor had Hickok and McCall ever been compan- ions. In fact, Hickok was not even a good card player, "I know," said Richardson, in a letter to the Neiv York Sun. "because 1 was there."' Richardson was indeed in Deadwood diat day and had made Hickok's personal acquaintance, Aldiough he did not witness the shooting, he arrived at die murder scene soon afterwards and wrote aliout the event at various times in later years. Richardson's testimony about events in Deadwood in 1876 has l")een used by numerous historians of the Black Hills gold rush and biographers of Wild Bill Hickok, but his credentials are rarely dis- I. Richardson, "Last Days of a Plainsman," True West 13 (Nov.-Dec. 1965): 22, "Last Days of a Phinsman" is actually a reprint of Richardson's lengthy letter to the Mew York Sun. -

1 Was Raised, " Remarked Dwight Eisenhower in a 1953 Speech, " in a Little Town...Called Abilene, Kansas. We Had As

WILD BILL HI CKOK IN ABI LENE ROBERT DYKSTRA '1 was raised, " remarked Dwight Eisenhower in a 1953 speech, " in a little town.... called Abilene, Kansas. We had as our marshal for a long time a man named Wild Bill Hickok. " The town had a code, said the Presi dent. "It was: Meet anyone face to face with whom you disagree.... If you met him face to face and took the same risks he did, you could get away with almost anything, as long as the bullet was in front. ftl This invoking of a curious nfair play" symbol in the depths of the McCarthy era illustrates per haps more pungently than could anything else the continuing status of James Butler Hickok (1837-1876) as a hero for Americans. Although no one • has yet attempted to trace the development or assess the impact of the Hickok image, American social and literary historians have, like Eisenhower, made use of it for some time. To Vernon L. Parrington, for example, Wild Bill was a symbol of Gilded Age extravagance ("All things were held cheap, and human life the cheapest of all"), 2 but more recently Professor Harvey Wish utilized him, rather less metaphorically, as the epitome of the "tough, straight-shooting" peace officer who brought law and order to the West. 3 As supplemented by his violent death in the Black Hills goldfields, Wild Bill!s modern reputation, it seems fair to say, rests indeed on his career as city marshal of Abilene in 1871. The questions being asked here are: How did the tradition of Hickok in Abilene arise ? And as it now stands does it or does it not reflect historical reality? This study will review what seems to be the most significant Hickok literature in an effort to answer the first of these questions. -

Review of Wild Bill Hickok: the Man and His Myth by Joseph G

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Winter 1998 Review of Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth By Joseph G. Rosa Thomas Dunlay University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Dunlay, Thomas, "Review of Wild Bill Hickok: The Man and His Myth By Joseph G. Rosa" (1998). Great Plains Quarterly. 2072. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2072 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BOOK REVIEWS 65 Myth credits Wild Bill with killing dozens or even hundreds of men; Rosa believes the actual toll to be about ten, making him far from one of the West's leading killers. His larger-than-life personality and physical pres ence struck the public fancy and have contin ued to do so, perhaps, Rosa suggests, because of a conformist society's need for a hero who was an individualist and who lived by his own principles rather than adapting to others' stan dards. He was undoubtedly highly skilled with a revolver, had extremely good reflexes, and was vigilant and watchful, as such men usually were. Rosa denies that he was a callous or psychotic killer, and the best evidence indi cates that he did not look for trouble.