PENTANGLE Established 1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Hughes' Family Films and Seriality

Article Title ‘Give people what they expect’: John Hughes’ Family Films and Seriality in 1990s Hollywood Author Details: Dr Holly Chard [email protected] Biography: Holly Chard is Lecturer in Contemporary Screen Media at the University of Brighton. Her research focuses on the U.S. media industries in the 1980s and 1990s. Her recent and forthcoming publications include: a chapter on Macaulay Culkin’s career as a child star, a monograph focusing on the work of John Hughes and a co- authored journal article on Hulk Hogan’s family films. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Frank Krutnik and Kathleen Loock for their invaluable feedback on this article and Daniel Chard for assistance with proofreading. 1 ‘Give people what they expect’: John Hughes’ Family Films and Seriality in 1990s Hollywood Keywords: seriality, Hollywood, comedy, family film Abstract: This article explores serial production strategies and textual seriality in Hollywood cinema during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Focusing on John Hughes’ ‘high concept’ family comedies, it examines how Hughes exploited the commercial opportunities offered by serial approaches to both production and film narrative. First, I consider why Hughes’ production set-up enabled him to standardize his movies and respond quickly to audience demand. My analysis then explores how the Home Alone films (1990-1997), Dennis the Menace (1993) and Baby’s Day Out (1994) balanced demands for textual repetition and novelty. Article: Described by the New York Times as ‘the most prolific independent filmmaker in Hollywood history’, John Hughes created and oversaw a vast number of movies in the 1980s and 1990s.1 In a period of roughly fourteen years, from the release of National Lampoon’s Vacation (Ramis, 1983) to the release of Home Alone 3 (Gosnell, 1997), Hughes received screenwriting credits on twenty-seven screenplays, of which he produced eighteen, directed eight and executive produced two. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

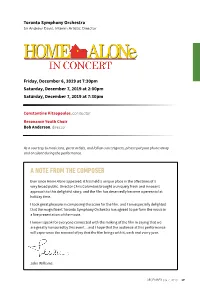

A Note from the Composer

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Friday, December 6, 2019 at 7:30pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 2:00pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 7:30pm Constantine Kitsopoulos, conductor Resonance Youth Choir Bob Anderson, director As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. A NOTE FROM THE COMPOSER Ever since Home Alone appeared, it has held a unique place in the affections of a very broad public. Director Chris Columbus brought a uniquely fresh and innocent approach to this delightful story, and the film has deservedly become a perennial at holiday time. I took great pleasure in composing the score for the film, and I am especially delighted that the magnificent Toronto Symphony Orchestra has agreed to perform the music in a live presentation of the movie. I know I speak for everyone connected with the making of the film in saying that we are greatly honoured by this event…and I hope that the audience at this performance will experience the renewal of joy that the film brings with it, each and every year. John Williams DECEMBER 6 & 7, 2019 17 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Presents A JOHN HUGHES Production A CHRIS COLUMBUS Film HOME ALONE Starring MACAULAY CULKIN JOE PESCI DANIEL STERN JOHN HEARD and CATHERINE O’HARA Music by JOHN WILLIAMS Film Editor RAJA GOSNELL Production Designer JOHN MUTO Director of Photography JULIO MACAT Executive Producers MARK LEVINSON & SCOTT ROSENFELT and TARQUIN GOTCH Written and Produced by JOHN HUGHES Directed by CHRIS COLUMBUS Soundtrack Album Available on CBS Records, Cassettes and Compact Discs Color by DELUXE® Tonight’s program is a presentation of the complete filmHome Alone with a live performance of the film’s entire score, including music played by the orchestra during the end credits. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

Ironwood Man's Trial Continues

DAYS ‘TIL Snow possible 10 CHRISTMAS High: 3 | Low: -6 | Details, page 2 The Best Gift for the Holidays is a Gift Certificate from: Ironwood, MI 906-932-4400 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Thursday, December 15, 2016 75 cents DRUG CASE DAY 2 GRTA receives trail Ironwood man’s approval By IAN MINIELLY [email protected] trial continues BESSEMER — After more than 1,000 hours of volunteer By RICHARD JENKINS across two people having car labor, placing signs and remov- [email protected] trouble that acknowledged being ing brush across the trail sys- BESSEMER — The trial of an at the house earlier and that tems, the Gogebic Range Trail Ironwood man charged with drugs and a gun were present. Authority obtained Department multiple drug and firearm The statements from these of Natural Resources signing felonies continued in Gogebic individuals — identified as and brushing approval for the County Circuit Court Wednes- Engles and Christine Leonzal — first time since 2010. day. was used as the basis for a The field contact from the Day 2 of the trial of Donovan search warrant of the property, DNR gave blanket approval Howard Payeur, 32, continued which resulted in the discovery after inspecting the snowmobile with more prosecution witnesses of a TEC-9 handgun and drugs, trails. testifying against Payeur; who is including crystal meth. At The GRTA is experiencing a standing trial on seven counts — around the time the house was revival through the efforts of its possession of methamphetamine searched, local law enforcement board of directors, with Deb Fer- with intent to deliver, conspira- officers also conducted a nearby gus, grant coordinator, spear- cy to possess methamphetamine traffic stop of a vehicle Payeur heading efforts nearly seven with intent to deliver, felon in was driving, which subsequently days-per-week to achieve possession of a weapon, felon in resulted in the discovery of a approval from the DNR. -

Mar.-Apr.2020 Highlites

Prospect Senior Center 6 Center Street Prospect, CT 06712 (203)758-5300 (203)758-3837 Fax Lucy Smegielski Mar.-Apr.2020 Director - Editor Municipal Agent Highlites Town of Prospect STAFF Lorraine Lori Susan Lirene Melody Matt Maglaris Anderson DaSilva Lorensen Heitz Kalitta From the Director… Dear Members… I believe in being upfront and addressing things head-on. Therefore, I am using this plat- form to address some issues that have come to my attention. Since the cost for out-of-town memberships to our Senior Center went up in January 2020, there have been a few miscon- ceptions that have come to my attention. First and foremost, the one rumor that I would definitely like to address is the story going around that the Prospect Town Council raised the dues of our out-of-town members because they are trying to “get rid” of the non-residents that come here. The story goes that the Town Council is trying to keep our Senior Center strictly for Prospect residents only. Nothing could be further from the truth. I value the out-of-town members who come here. I feel they have contributed significantly to the growth of our Senior Center. Many of these members run programs here and volun- teer in a number of different capacities. They are my lifeline and help me in ways that I could never repay them for. I and the Town Council members would never want to “get rid” of them. I will tell you point blank why the Town Council decided to raise membership dues for out- of-town members. -

Saturday, July 7, 2018 | 15 | WATCH Monday, July 9

6$785'$<-8/< 7+,6,6123,&1,& _ )22' ,16,'( 7+,6 :((. 6+233,1* :,1(6 1$',<$ %5($.6 &KHFNRXW WKH EHVW LQ ERWWOH 683(50$5.(7 %(67 %8<6 *UDE WKH ODWHVW GHDOV 75,(' $1' 7(67(' $// 7+( 58/(6 :H FKHFN RXW WRS WUDYHO 1$',<$ +XVVDLQ LV D KDLUGU\HUV WR ORRN ZDQWDQGWKDW©VZK\,IHHOVR \RXGRQ©WHDWZKDW\RX©UHJLYHQ WRWDO UXOHEUHDNHU OXFN\§ WKHQ \RX JR WR EHG KXQJU\§ JRRG RQ WKH PRYH WKHVH GD\V ¦,©P D 6KH©V ZRQ 7KLV UHFLSH FROOHFWLRQ DOVR VHHV /XFNLO\ VKH DQG KXVEDQG $EGDO SDUW RI WZR YHU\ %DNH 2II SXW KHU IOLS D EDNHG FKHHVHFDNH KDYH PDQDJHG WR SURGXFH RXW D VOHZ RI XSVLGH GRZQ PDNH D VLQJOH FKLOGUHQ WKDW DUHQ©W IXVV\HDWHUV GLIIHUHQW ZRUOGV ¤ ,©P %ULWLVK HFODLU LQWR D FRORVVDO FDNH\UROO VR PXFK VR WKDW WKH ZHHN EHIRUH 5(/$; DQG ,©P %DQJODGHVKL§ WKH FRRNERRNV DQG LV DOZD\V LQYHQW D ILVK ILQJHU ODVDJQH ZH FKDW VKH KDG DOO WKUHH *$0(6 $336 \HDUROG H[SODLQV ¦DQG UHDOO\ VZDS WKH SUDZQ LQ EHJJLQJ KHU WR GROH RXW IUDJUDQW &RQMXUH XS RQ WKH WHOO\ ¤ SUDZQ WRDVW IRU FKLFNHQ DQG ERZOIXOV RI ILVK KHDG FXUU\ EHFDXVH ,©P SDUW RI WKHVH 1DGL\D +XVVDLQ PDJLFDO DWPRVSKHUH WZR DPD]LQJ ZRUOGV , KDYH ¦VSLNH§ D GLVK RI PDFDURQL ¦7KH\ ZHUH DOO RYHU LW OLNH WHOOV (//$ FKHHVH ZLWK SLFFDOLOOL ¤ WKH ¨0XPP\ 3OHDVH FDQ ZH KDYH 086,& QR UXOHV DQG QR UHVWULFWLRQV§ :$/.(5 WKDW 5(/($6(6 ZRPDQ©V D PDYHULFN WKDW ULJKW QRZ"© , ZDV OLNH ¨1R +HQFH ZK\ WKUHH \HDUV RQ IURP IRRG LV PHDQW +RZHYHU KHU DSSURDFK WR WKDW©V WRPRUURZ©V GLQQHU ,©YH :H OLVWHQ WR WKH ZLQQLQJ *UHDW %ULWLVK %DNH 2II WR EH IXQ FODVKLQJDQG PL[LQJ IODYRXUVDQG MXVW FRRNHG LW HDUO\ \RX©YH JRW ODWHVW DOEXPV WKH /XWRQERUQ -

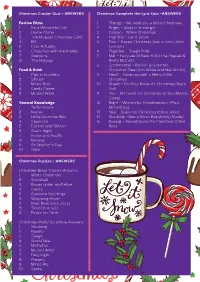

Christmas Cracker Quiz - ANSWERS Christmas Complete the Lyric Quiz -ANSWERS

Christmas Cracker Quiz - ANSWERS Christmas Complete the Lyric Quiz -ANSWERS Festive Films 1. Tidings – We wish you a Merry Christmas 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 2. Bright – Away in a manger 2. Home Alone 3. Glisten – White Christmas 3. The Muppet Christmas Carol 4. Frightful – Let it Snow 4. Elf 5. Fear – Happy Christmas (war is over) John 5. Love Actually Lennon) 6. Christmas with the Kranks 6. Together – Sleigh Ride 7. Gremlins 7. Met – Fairytale of New York (The Pogues & 8. The Holiday Kirsty McColl) 8. Sentimental – Rockin’ around the Food & Drink Christmas Tree (Kim Wilde and Mel Smith) 1. Pigs in blankets 9. Heart – Have yourself a Merry little 2. Stollen Christmas 3. Mince Pies 10. Shade – Do they Know it’s Christmas (Band 4. Candy Canes Aid) 5. Mulled Wine 11. You – All I want for Christmas is You (Mariah Carey) General Knowledge 12. Right – Wonderful Christmastime (Paul 1. Turtle Doves McCartney) 2. Narnia 13. Year – Step into Christmas (Elton John) 3. Little Drummer Boy 14. Stocking – Merry Xmas Everybody (Slade) 4. Capricorn 15. Driving – Driving home for Christmas (Chris 5. Donner and Blitzen Rea) 6. Silent Night 7. Indian and Pacific 8. Norway 9. St Stephen’s Day 10. 1984 Christmas Puzzles - ANSWERS Christmas Brain Teasers Answers 1. White Christmas 2. Snowball 3. Kisses under mistletoe 4. Carols 5. Season’s Greetings 6. Wrapping Paper 7. Noel Noel (no L, no L) 8. Tinsel (t in sel) 9. Peace on Earth Christmas World Scramble Answers 1. Stocking 2. Bauble 3. Sleigh 4. Snowflake 5. Mistletoe 6. -

HUK+Adult+FW1920+Catalogue+-+

Saving You By (author) Charlotte Nash Sep 17, 2019 | Paperback $24.99 | Three escaped pensioners. One single mother. A road trip to rescue her son. The new emotionally compelling page-turner by Australia's Charlotte Nash In their tiny pale green cottage under the trees, Mallory Cook and her five-year- old son, Harry, are a little family unit who weather the storms of life together. Money is tight after Harry's father, Duncan, abandoned them to expand his business in New York. So when Duncan fails to return Harry after a visit, Mallory boards a plane to bring her son home any way she can. During the journey, a chance encounter with three retirees on the run from their care home leads Mallory on an unlikely group road trip across the United States. 9780733636479 Zadie, Ernie and Jock each have their own reasons for making the journey and English along the way the four of them will learn the lengths they will travel to save each other - and themselves. 384 pages Saving You is the beautiful, emotionally compelling page-turner by Charlotte Nash, bestselling Australian author of The Horseman and The Paris Wedding. Subject If you love the stories of Jojo Moyes and Fiona McCallum you will devour this FICTION / Family Life / General book. 'I was enthralled... Nash's skilled storytelling will keep you turning pages until Distributor the very end.' FLEUR McDONALD Hachette Book Group Contributor Bio Charlotte Nash is the bestselling author of six novels, including four set in country Australia, and The Paris Wedding, which has been sold in eight countries and translated into multiple languages. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie -

April 14, 2019 Palm Sunday

APRIL 14, 2019 PALM SUNDAY 13900 BISCAYNE AVE. W ROSEMOUNT, MN 55068 PHONE: 651-423-4402 www.stjosephcommunity.org Weekend Mass times: Saturday: 5:00 pm Sunday: 7 am, 8:30 am, & 10:30 am Family Formation Nights! Elementary Grades 1-5 First Wednesdays of the Month Every first Wednesday of the month during the school year we will gather as families in place of a regular Faith Formation night! All Faith Formation, School, and Parish Families are invited to gather together to grow deeper in faith through dynamic NEW Curriculum! Children will dive into Bible speakers, prayer and activities. stories, connect them with Catholicism, and be called into action to live out the faith every week. Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Middle School Grades 6-8 The Catechesis of the Good Shepherd (CGS) program continues to grow and we are excited Grade 6 - Encounter to be adding our first Level III group! A Bible study specifically designed Level I - Sundays for PreK-K for Middle School youth! Through Level II - Wednesdays for Grades 1-3 DVD presentations and small group Level III - Tuesdays for Grades 4-6 discussion, youth are drawn into the Salvation story and who God is. Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Open House Grades 7 & 8 - Altaration Sunday Morning, May 19th Youth learn about the beauty and mystery of the Mass through DVD presentations and small group Confirmation Preparation discussions. NEW Program Design! Beginning with the 2019-2020 school year, Confirmation preparation will be incorporated into High School Grades 9-12 the High School Wednesday night formation! Preparation will take place in 10th Grade.