The Reign of Franchise Filmmaking in Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Hughes' Family Films and Seriality

Article Title ‘Give people what they expect’: John Hughes’ Family Films and Seriality in 1990s Hollywood Author Details: Dr Holly Chard [email protected] Biography: Holly Chard is Lecturer in Contemporary Screen Media at the University of Brighton. Her research focuses on the U.S. media industries in the 1980s and 1990s. Her recent and forthcoming publications include: a chapter on Macaulay Culkin’s career as a child star, a monograph focusing on the work of John Hughes and a co- authored journal article on Hulk Hogan’s family films. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Frank Krutnik and Kathleen Loock for their invaluable feedback on this article and Daniel Chard for assistance with proofreading. 1 ‘Give people what they expect’: John Hughes’ Family Films and Seriality in 1990s Hollywood Keywords: seriality, Hollywood, comedy, family film Abstract: This article explores serial production strategies and textual seriality in Hollywood cinema during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Focusing on John Hughes’ ‘high concept’ family comedies, it examines how Hughes exploited the commercial opportunities offered by serial approaches to both production and film narrative. First, I consider why Hughes’ production set-up enabled him to standardize his movies and respond quickly to audience demand. My analysis then explores how the Home Alone films (1990-1997), Dennis the Menace (1993) and Baby’s Day Out (1994) balanced demands for textual repetition and novelty. Article: Described by the New York Times as ‘the most prolific independent filmmaker in Hollywood history’, John Hughes created and oversaw a vast number of movies in the 1980s and 1990s.1 In a period of roughly fourteen years, from the release of National Lampoon’s Vacation (Ramis, 1983) to the release of Home Alone 3 (Gosnell, 1997), Hughes received screenwriting credits on twenty-seven screenplays, of which he produced eighteen, directed eight and executive produced two. -

A Note from the Composer

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Friday, December 6, 2019 at 7:30pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 2:00pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 7:30pm Constantine Kitsopoulos, conductor Resonance Youth Choir Bob Anderson, director As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. A NOTE FROM THE COMPOSER Ever since Home Alone appeared, it has held a unique place in the affections of a very broad public. Director Chris Columbus brought a uniquely fresh and innocent approach to this delightful story, and the film has deservedly become a perennial at holiday time. I took great pleasure in composing the score for the film, and I am especially delighted that the magnificent Toronto Symphony Orchestra has agreed to perform the music in a live presentation of the movie. I know I speak for everyone connected with the making of the film in saying that we are greatly honoured by this event…and I hope that the audience at this performance will experience the renewal of joy that the film brings with it, each and every year. John Williams DECEMBER 6 & 7, 2019 17 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Presents A JOHN HUGHES Production A CHRIS COLUMBUS Film HOME ALONE Starring MACAULAY CULKIN JOE PESCI DANIEL STERN JOHN HEARD and CATHERINE O’HARA Music by JOHN WILLIAMS Film Editor RAJA GOSNELL Production Designer JOHN MUTO Director of Photography JULIO MACAT Executive Producers MARK LEVINSON & SCOTT ROSENFELT and TARQUIN GOTCH Written and Produced by JOHN HUGHES Directed by CHRIS COLUMBUS Soundtrack Album Available on CBS Records, Cassettes and Compact Discs Color by DELUXE® Tonight’s program is a presentation of the complete filmHome Alone with a live performance of the film’s entire score, including music played by the orchestra during the end credits. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

Mar.-Apr.2020 Highlites

Prospect Senior Center 6 Center Street Prospect, CT 06712 (203)758-5300 (203)758-3837 Fax Lucy Smegielski Mar.-Apr.2020 Director - Editor Municipal Agent Highlites Town of Prospect STAFF Lorraine Lori Susan Lirene Melody Matt Maglaris Anderson DaSilva Lorensen Heitz Kalitta From the Director… Dear Members… I believe in being upfront and addressing things head-on. Therefore, I am using this plat- form to address some issues that have come to my attention. Since the cost for out-of-town memberships to our Senior Center went up in January 2020, there have been a few miscon- ceptions that have come to my attention. First and foremost, the one rumor that I would definitely like to address is the story going around that the Prospect Town Council raised the dues of our out-of-town members because they are trying to “get rid” of the non-residents that come here. The story goes that the Town Council is trying to keep our Senior Center strictly for Prospect residents only. Nothing could be further from the truth. I value the out-of-town members who come here. I feel they have contributed significantly to the growth of our Senior Center. Many of these members run programs here and volun- teer in a number of different capacities. They are my lifeline and help me in ways that I could never repay them for. I and the Town Council members would never want to “get rid” of them. I will tell you point blank why the Town Council decided to raise membership dues for out- of-town members. -

The Principality of Monaco Proudly Supports the World's Premiere Of

THE PRINCIPALITY OF MONACO PROUDLY SUPPORTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF DISNEYNATURE’S OCEANS “...We all share the environment; its protection is our duty.” H.S.H. Prince Albert II of Monaco HOLLYWOOD, California – April 19, 2010 – As 2010 marks the 100th anniversary of Monaco’s worldrenowned Oceanographic Museum and Aquarium, it is especially fitting that the Principality, the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation and the Oceanographic Institute Foundation Albert I, Prince of Monaco – all proud, longtime supporters of OCEANS – joined to celebrate the world premiere of this extraordinary motion picture. The starstudded blue carpet screening of “Disneynature’s Oceans” at the legendary El Capitan Theatre included the film’s narrator, Pierce Brosnan, the duo who sing the film’s theme song, “Make A Wave”, Demi Lovato and Joe Jonas along with his brothers Nick and Kevin renowned oceanographer and National Geographic ExplorerinResidence, Sylvia Earle, the grandson and granddaughter of famed ocean explorer JacquesYves Cousteau, Fabien & Celine Cousteau, the world’s foremost ocean artist, Wyland along with some of the film’s crew members and highranking executives from the Walt Disney Company, including president and CEO Bob Iger, chairman of the Walt Disney Studios Rich Ross and president Alan Bergman and executive vice president and general manager of Disneynature JeanFrancois Camilleri. Representing the Principality of Monaco was Maguy Maccario, vice president of the US chapter of the Prince’s Foundation and consul general in New York. Stars who brought along their children included Brothers & Sister star Gilles Marini, actress and model Amber Valetta, actress Lolita Davidovich and film director husband Ron Shelton, and actress Joely Fisher. -

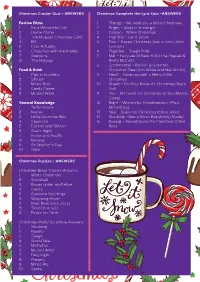

Christmas Cracker Quiz - ANSWERS Christmas Complete the Lyric Quiz -ANSWERS

Christmas Cracker Quiz - ANSWERS Christmas Complete the Lyric Quiz -ANSWERS Festive Films 1. Tidings – We wish you a Merry Christmas 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 2. Bright – Away in a manger 2. Home Alone 3. Glisten – White Christmas 3. The Muppet Christmas Carol 4. Frightful – Let it Snow 4. Elf 5. Fear – Happy Christmas (war is over) John 5. Love Actually Lennon) 6. Christmas with the Kranks 6. Together – Sleigh Ride 7. Gremlins 7. Met – Fairytale of New York (The Pogues & 8. The Holiday Kirsty McColl) 8. Sentimental – Rockin’ around the Food & Drink Christmas Tree (Kim Wilde and Mel Smith) 1. Pigs in blankets 9. Heart – Have yourself a Merry little 2. Stollen Christmas 3. Mince Pies 10. Shade – Do they Know it’s Christmas (Band 4. Candy Canes Aid) 5. Mulled Wine 11. You – All I want for Christmas is You (Mariah Carey) General Knowledge 12. Right – Wonderful Christmastime (Paul 1. Turtle Doves McCartney) 2. Narnia 13. Year – Step into Christmas (Elton John) 3. Little Drummer Boy 14. Stocking – Merry Xmas Everybody (Slade) 4. Capricorn 15. Driving – Driving home for Christmas (Chris 5. Donner and Blitzen Rea) 6. Silent Night 7. Indian and Pacific 8. Norway 9. St Stephen’s Day 10. 1984 Christmas Puzzles - ANSWERS Christmas Brain Teasers Answers 1. White Christmas 2. Snowball 3. Kisses under mistletoe 4. Carols 5. Season’s Greetings 6. Wrapping Paper 7. Noel Noel (no L, no L) 8. Tinsel (t in sel) 9. Peace on Earth Christmas World Scramble Answers 1. Stocking 2. Bauble 3. Sleigh 4. Snowflake 5. Mistletoe 6. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie -

Fact Book 2010

Fact Book 2010 Fact Book 2010 MANAGEMENT TEAM Board of Directors 3 Senior Corporate Officers 4 Principal Businesses 5 OPERATIONS DATA Studio Entertainment 6 Parks and Resorts 8 Consumer Products 11 Media Networks 12 Interactive Media 15 COMPANY HISTORY 2010 17 2009 - 1999 18 - 21 1998 - 1923 22 - 25 Table of Contents 2 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Susan E. Arnold John E. Bryson John S. Chen Judith L. Estrin Robert A. Iger Director since 2007 Director since 2000 Director since 2004 Director since 1998 Director since 2000 Steve Jobs Fred H. Langhammer Aylwin B. Lewis Monica C. Lozano Robert W. Matschullat Director since 2006 Director since 2005 Director since 2004 Director since 2000 Director since 2002 John E. Pepper, Jr. Sheryl Sandberg Orin C. Smith Chairman of the Board Director since 2010 Director since 2006 since 2007 Management Team 3 SENIOR CORPORATE OFFICERS Robert A. Iger President and Chief Executive Officer Jay Rasulo Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Alan N. Braverman Senior Executive Vice President, General Counsel and Secretary Jayne Parker Executive Vice President and Chief Human Resources Officer Christine M. McCarthy Executive Vice President, Corporate Real Estate, Sourcing, Alliances, and Treasurer Kevin A. Mayer Executive Vice President, Corporate Strategy and Business Development Zenia B. Mucha Executive Vice President, Corporate Communications Ronald L. Iden Senior Vice President, Global Security Brent A. Woodford Senior Vice President, Planning and Control Management Team 4 PRINCIPAL BUSINESSES STUDIO ENTERTAINMENT Rich Ross Chairman, The Walt Disney Studios PARKS AND RESORTS Thomas O. Staggs Chairman, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Worldwide MEDIA NETWORKS George W. -

Stanley S. Hubbard, Chair

OnBroadcasters The Foundation ofAir America Spring 2008 Mission Statement The mission of the Broadcasters Foundation of America is to improve the quality of life and maintain the personal dignity of men and women in the radio and television broadcast profession who find themselves in acute need. The foundation reaches out across the country to identify and provide an anonymous safety net in cases of critical illness, advanced age, death of a spouse, accident and other serious misfortune. 2008 Golden Mike Table Of Contents Page 2008 Golden Mike ....... 3-37 3 2008 Pioneer Awards ...40-48 2008 Offshore Weekend .................50-51 Taishoff Foundation Underwrites Annual Report ...............54 Message from the President ................55 On The Air Volume 12 • Issue 1 • Spring 2008 © On the Air is a free news and feature publication, offered to Broadcasters Foundation of America members and friends and is published three times a year by the : Broadcasters Foundation of America Seven Lincoln Avenue Second Floor Greenwich, CT 06830 www.broadcastersfoundation.org Ward L. Quaal Gordon H. Hastings, Publisher Jamie Russo, Creative Director For feature story contributions or to request another copy of this publication, please call the Broadcasters Foundation of America at 203-862-8577, or you may email any questions and/or 2008 Ward L. Quall Pioneer Awards comments to Gordon H. Hastings at [email protected] Page 40 The 2007 Pioneer Awards 3 On The Air Summer 2007 2007 Celebrity Golf Wee Burn Challenges Record Field The Darien Connecticut Club Praised Among The Very Best 4 On The Air Summer 2007 Broadcasters Foundation of America President Gordon Hastings, Anne Sweeney, Foundation Chair Phil Lombardo and Anne’s daughter Rosemary “I’m so grateful to see so many friends here, so many people I’ve met and learned from. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

"It's Aimed at Kids - the Kid in Everybody": George Lucas, Star Wars and Children's Entertainment by Peter Krämer, University of East Anglia, UK

"It's aimed at kids - the kid in everybody": George Lucas, Star Wars and Children's Entertainment By Peter Krämer, University of East Anglia, UK When Star Wars was released in May 1977, Time magazine hailed it as "The Year's Best Movie" and characterised the special quality of the film with the statement: "It's aimed at kids - the kid in everybody" (Anon., 1977). Many film scholars, highly critical of the aesthetic and ideological preoccupations of Star Wars and of contemporary Hollywood cinema in general, have elaborated on the second part in Time magazine's formula. They have argued that Star Wars is indeed aimed at "the kid in everybody", that is it invites adult spectators to regress to an earlier phase in their social and psychic development and to indulge in infantile fantasies of omnipotence and oedipal strife as well as nostalgically returning to an earlier period in history (the 1950s) when they were kids and the world around them could be imagined as a better place. For these scholars, much of post-1977 Hollywood cinema is characterised by such infantilisation, regression and nostalgia (see, for example, Wood, 1985). I will return to this ideological critique at the end of this essay. For now, however, I want to address a different set of questions about production and marketing strategies as well as actual audiences: What about the first part of Time magazine's formula? Was Star Wars aimed at children? If it was, how did it try to appeal to them, and did it succeed? I am going to address these questions first of all by looking forward from 1977 to the status Star Wars has achieved in the popular culture of the late 1990s.