Texas Juvenile Justice Department State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAP Crystal Reports

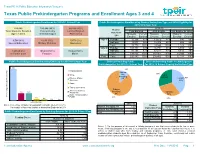

Texas PK-16 Public Education Information Resource Texas Public Prekindergarten Programs and Enrollment Ages 3 and 4 Public Prekindergarten Enrollment for 2015-16 School Year Public Prekindergarten Enrollment by Student Instruction Type and ADA Eligibility for 2015-16 School Year 220,640 190,848 (86%) 88,295 (40%) 2015-16 Student Total Students Enrolled Economically Limited English Total Enrolled ADA Eligible Not Eligible for ADA Instruction Ages 3 and 4 Disadvantaged Proficiency Type Students Percent Students Percent Students Percent Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled 8,594 (4%) 6,611 (3%) 5,471 (2%) Age 3 Full-day 12,206 47% 11,616 47% 590 50% Special Education Military Children Homeless Half-day 13,573 53% 12,974 53% 599 50% Total 25,779 100% 24,590 100% 1,189 100% Age 4 Full-day 103,380 53% 96,791 53% 6,589 60% 1,695 (0.8%) 109,816 (50%) 110,824 (50%) Half-day 91,481 47% 87,071 47% 4,410 40% In Foster Care Females Males Total 194,861 100% 183,862 100% 10,999 100% Total Total 220,640 100% 208,452 100% 12,188 100% Public Prekindergarten Enrollment by Ethnicity for 2015-16 School Year Districts Providing Public Districts Providing Public Prekindergarten Prekindergarten for 2015-16 School Year for 2015-16 School Year by Instruction Type 64% 13% Hispanic/Latino Districts 30% White Not Full & Providing Half-day 40% Black or African PK Full-Day American Only Asian Two or more races Districts American Indian or Providing 15% 15% Alaska Nat Half-Day PK Native Hawaiian/Other Only Percentage of Students Enrolled Students of -

Texas Youth Commission (TYC) and Transferred All Functions, Duties and Responsibilities of These Former Agencies to TJJD

Comprehensive Report Youth Reentry and Reintegration December 1, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................... 1 ASSESSMENTS ............................................................................................................................ 1 PROGRAMS ................................................................................................................................ 2 NETWORK OF TRANSITION PROGRAMS .................................................................................... 5 IDENTIFICATION OF LOCAL PROVIDERS AND TRANSITIONAL SERVICES .................................... 7 Children’s Aftercare Reentry Experience (CARE) ................................................................ 9 Gang Intervention Treatment: Reentry Development for Youth (GitRedy) ....................... 9 SHARING OF INFORMATION .................................................................................................... 10 OUTCOMES ................................................................................................................................. 10 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................ 14 APPENDICES .............................................................................................................................. -

The Texas Youth Commission

JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE OPERATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE TEXAS YOUTH COMMISSION PRELIMINARY REPORT OF INITIAL FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS A REPORT TO THE LT. GOVERNOR AND THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE 80TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE JOHN WHITMIRE JERRY MADDEN SENATE CO-CHAIRMAN HOUSE CO-CHAIRMAN Joint Select Committee on the Operation and Management of the Texas Youth Commission Preliminary Report of Initial Findings and Recommendations Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Preliminary Report III. Proclamation IV. Attachment One - Recommended Action Plan by Committee V. Attachment Two - Statistical Breakdown by TDCJ-OIG VI. Attachment Three - Filed Legislation VII. Attachment Four - State Auditor's Report 07-022 VIII. Attachment Five - McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility - Case File Review EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background The Texas Youth Commission (TYC) is the state agency responsible for the care, custody and rehabilitation of the juvenile offenders who have been committed by the court. The ages of youth committed to TYC ranges from 10 to 17. The TYC can maintain custody of the youth until the age of twenty-one (21). Allegations of mistreatment, disturbances and abuse began to surface and the TYC came under federal scrutiny due to the riot at the Evins Regional Juvenile Center in Edinburg, Texas. The U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, began an investigation at the Evins facility in September 2006 and issued their report on March 15, 2007, stating "certain conditions at Evins violate the constitutional rights of the youth". The Senate Criminal Justice Committee, the House Corrections Committee and the Juvenile Justice and Family Issues Committee conducted separate public hearings allowing staff, youth, family members, child advocacy groups, the ACLU and other concerned citizens to be heard. -

Texas Education Agency Overview

Texas Education Agency Overview 100 - Office of the Commissioner; Senior Policy Advisor The Commissioner's Office provides leadership to schools, manages the Texas Education Agency (TEA), and provides coordination with the state legislature and other branches of state government as well as the U. S. Department of Education. SBOE activities and rules, commissioner rules and regulations, commissioner hearing decisions, coordinates with state legislature, Commissioner’s Correspondence and Complaints Management. Number of FTEs: 6 Correspondence Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to correspondence received by members of the public, local education agencies (LEAs), legislature, and other state agencies. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 03-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function serves as a review and distribution center for correspondence assigned to other offices in coordination with Complaints Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. Complaints Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to complaints received by members of the public. Through various activities, this function ensures that the operations of the Agency’s complaint system is compliant with applicable regulations and policy and effectively meets identified needs of the Agency. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 04-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function mainly serves as a review and distribution center for complaints assigned to other offices in coordination with Correspondence Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. -

Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS

STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS Report to the Governor October 2009 Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR OCTOBER 2009 TEXAS GENERAL LAND OFFICE JERRY PATTERSON, COMMISSIONER INTRODUCTION SB 1262 Summary Texas Natural Resources Code, Chapter 31, Subchapter E, [Senate Bill 1262, 74th Texas Legislature, 1995] amended two years of previous law related to the reporting and disposition of state agency land. The amendments established a more streamlined process for disposing of unused or underused agency land by defining a reporting and review sequence between the Land Commissioner and the Governor. Under this process, the Asset Management Division of the General Land Office provides the Governor with a list of state agency properties that have been identified as unused or underused and a set of recommended real estate transactions. The Governor has 90 days to approve or disapprove the recommendations, after which time the Land Commissioner is authorized to conduct the approved transactions. The statute freezes the ability of land-owning state agencies to change the use or dispose of properties that have recommended transactions, from the time the list is provided to the Governor to a date two years after the recommendation is approved by the Governor. Agencies have the opportunity to submit to the Governor development plans for the future use of the property within 60 days of the listing date, for the purpose of providing information on which to base a decision regarding the recommendations. The General Land Office may deduct expenses from transaction proceeds. -

UCC Meeting – August 17, 2010 – Foundation Board Room

UCC Meeting – August 17, 2010 – Foundation Board Room Members present: Jennell Charles, Nikki Finlay; Anthony Giovannetti, Susan Hornbuckle; Todd Janke; Tatiana Krivosheev; Samuel Maddox, Kelli Nipper; Chris Raridan, Joan Taylor; Robert Vaughn, J. Celeste Walley-Jean, Ximena Zornosa. Finlay called the meeting to order at approximately 11:30 a.m. Approval of Minutes: Minutes were tabled Old Business: BA in Philosophy The committee reviewed a revised proposal for a BA degree with a major in Philosophy. The program was approved in 2007, but was never sent to the BOR. With minor corrections the revised proposal was approved. Meeting was adjourned at noon. Submitted by: Nikki Finlay To: CAPC CC: Michael Crafton, Robert Vaughn, Nasser Momayezi, John Campbell, Randy Rosenburg, Stephen Burnett, Joe Johnson, Ron Jackson, Todd Janke From: Alex Hall Date: July 30, 2010 Reg: New Philosophy BA Proposal / Instructional Support for Philosophy Major _________________________________________________________________ CAPC approved a Proposal for a Philosophy Major at Clayton State University in May, 2007. The revised proposal is nearly identical to the previously approved proposal, differing substantially in only two areas: 1. The original proposal offered an internship (in keeping with the general practice of the now dissolved Department of Communicative Arts and Integrative Studies). The new proposal eliminates the internship, which is no longer needed in order to align with departmental priorities. 2. The new proposal offers two concentrations, in Pre Law and Ethical Studies. The original proposal did not have any concentrations. These additional offerings enhance the value of the major. Regarding Instructional Support: 1. Two new lectureships have been created to support the Philosophy Program at Clayton. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas

JuvenilesJuveniles inin thethe AdultAdult CriminalCriminal JusticeJustice SystemSystem inin TexasTexas by Michele Deitch Special Project Report Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas By Project Director Michele Deitch, J.D., M.Sc., Senior Lecturer LBJ School of Public Affairs Student Participants Emily Ling, LBJ School of Public Affairs Emma Quintero, University of Texas School of Law Suggested citation for this report: Michele Deitch (2011). Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas, Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, LBJ School of Public Affairs A Special Project Report from the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin Applied Research in Juvenile and Criminal Justice—Fall Semester 2010 March 2011 © 2011 by The University of Texas at Austin All rights reserved. Cover design by Doug Marshall, LBJ School Communications Office Cover photo by Steve Liss/The AmericanPoverty.org Campaign TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures v Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary x Part I: Introduction 1 A. Purpose of Report 1 B. Methodology 2 C. Structure of Report 2 Part II: Overview 3 A. Historical Background 3 B. Sentencing and Transfer Options for Serious Juvenile Offenders Under Texas Law 4 C. Problems with Confining Juveniles in Adult Prisons and Jails 6 Part III: Findings 9 A. Numbers of adult certification cases vs. juvenile determinate sentencing 9 B. Characteristics of certified and determinate sentence populations 10 (1) Demographics 10 Age 10 Gender 11 Ethnicity 12 County of Conviction 12 (2) Criminal Offense 13 (3) Criminal History 16 Prior Referrals to Juvenile Court 17 Prior Referrals to Juvenile Court for Violent Offenses 17 Prior TYC Commitments 18 C. -

Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio History Faculty Publications College of Arts and Sciences 2004 Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas William S. Bush Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/hist_faculty Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Copyright by William Sebastian Bush 2004 The Dissertation Committee for William Sebastian Bush Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas Committee: Mark C. Smith, Supervisor Janet Davis Julia Mickenberg King Davis Sheldon Ekland-Olson Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas by William Sebastian Bush, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2004 Dedication For Mary and Alexander Acknowledgements Researching and writing a dissertation tests the emotions as well as the intellect. The two become so closely intertwined that scholarly advice invariably doubles as a salve for personal anxieties. Whether they knew it or not, practically everyone mentioned below bolstered my ever-flagging confidence even as they talked out ideas or problems that seemed bound within the more detached constraints of a dissertation project. Others just listened patiently to barely coherent thesis ideas, anxious brainstorming outbursts, and the usual angry tirades against academia. -

Chapter 10. Texas Dispositional Alternatives Danny Pirtile Introduction Juvenile Judges and District Attorneys Play an Important

Chapter 10. Texas Dispositional Alternatives Danny Pirtile Introduction Juvenile judges and district attorneys play an important role in determining appropriate and often-necessary sanctions for those youth deemed delinquent and incorrigible. In the late 1980s, there was a transitional period for the juvenile justice system, where state legislatures began to institute policies aimed at violent, serious, and chronic juvenile offenders (Snyder & Sickmund, 1995; TJPC, 2003). Texas was not immune to the dramatic policy shifts being initiated during the late 1980s and early 1990s that was due to an overwhelming increase in juvenile crime and public fear of habitual and violent youthful offenders. Cox, Conrad, Allen and Hanser (2007) present a plethora of programs and dispositional choices available to juvenile justice officials. This chapter presents dispositional programs available to Texas juvenile officials and the milieu of these dispositions. Texas lawmakers developed policies that sought to decrease the non-adversarial nature of the juvenile court and replace them with increased procedural similarities to the adult criminal justice system. These legislative changes resulted in the creation of laws that significantly altered dispositions or adjudicatory outcomes in the juvenile justice system. Juvenile judges and prosecutors received increased authority and were provided with a wide range of dispositional alternatives which included placing a youth on probation to transferring the case to the adult system. Thus, the new goal was to focus more on providing tougher, offense based sanctions, while still retaining some of the safeguards provided in the juvenile justice system, which ultimately rely on the parens patriae doctrine of rehabilitation and focus on the best interests of the child. -

UNT-0020-0177.Pdf

TxD Y200.6 J826 95/09 i1OCUMEN!TSW0 :VTRV 95-28JAN0. i9; Texas Youth Commission September 1995, Fall Issue 4900 N. Lamar, Austin, TX 78765 News and Information from throughout the Agency Lindgren resigns; Briscoe named acting de puty director In this issue: ay Lindgren, Deputy Executive Direc- Lindgren's duties in Rhode Island will tor of the Youth Ccommission since include responsibility for youth correction Marlin 'Reception January 15, 1988, as resigned to ac- juvenile probation, pretrial detention, men- cept the position of Director of the Rhode tal health services for children, and child Center' opens Island Department of Children, Youth and protective services. His appointment was Story on page 7. Families, effective August 15. made by Rhode Island Governor Lincoln Executive Director Steve Robinson ap- Almond. pointed Judy Briscoe, TYC's Director of "It has been an honor to serve on what Outstanding 1995 Delinquency Prevention, as acting deputy I am certain is the best juvenile corrections director. Employees Honored (rontinuedd o"rpage ) Stories and photospages 11-16. IN THIS ISSUE Legislation.................................. 3 Annual Workshop.........................11 Construction Contract .................. 15 RIF Policy......................................23 New Administrators.................23 m SanctionSancion Unit......25nit.................................2 Former TYC Board Member Lary York, center was honored when the TYC halfway house in Corpus Christi was renamed York House. Also pictured are current Board Chairman Gary D. Project RIO....................................26 Compton ofAmarillo, left, and State Senator John Montford ofLubbock; keynote speaker SECTIONS Halfway house renamed to Around TYC ............................... 3 honor former Board Member Volunteers ............. 18 e Corpus Christi halfway house, formerly called Nueces House for the county in Youth g ........................ -

Understanding and Addressing Youth Violence in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department

UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING YOUTH VIOLENCE IN THE TEXAS JUVENILE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT Report to the Office of the Independent Ombudsman by Michele Deitch, J.D., M.Sc. Amy Madore Kate Vickery Alycia Welch SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT Understanding and Addressing Youth Violence in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department Report to the Office of the Independent Ombudsman by Project Director Michele Deitch, J.D., M.Sc. Senior Lecturer, LBJ School of Public Affairs LBJ School Student Participants Amy Madore Kate Vickery Alycia Welch Special Project Report Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 ISBN: 978-89940-924-5 © 2013 by the University of Texas at Austin All rights reserved. Table of Contents Acknowledgements vii Executive Summmary ix List of Findings xix List of Tables and Figures xxv Chapter I: Introduction 1 A. Origins of the Report 1 B. Purpose of the Report 2 C. Methodology 2 D. Structure of the Report 4 Chapter II: Background 7 A. TYC Crisis of 2007 7 B. Reform Efforts Since 2007 8 (1) Senate Bill 103 8 (2) Reduction in Population and Closure of Facilities 9 (3) Shift Towards Treatment-Oriented Approach 10 C. Major Operational Changes and Challenges at TYC 11 (1) Use of Force and Use of Pepper Spray 11 (2) Staffing Shortages 11 (3) Sexual Assault Allegations 12 D. Creation of Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) 12 E. Recent Reports about Violence in TJJD 13 v Understanding and Addressing Youth Violence in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department Chapter III: A Profile of Violence in TJJD’s Secure Facilities 15 A.