Ruskin College and the Early Years of the History Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Develop Your Workforce Employer’S Guide to Higher Education This Booklet Sets out to Explain How Higher Level Skills Can Benefit Your Business

Develop your workforce Employer’s Guide to Higher Education This booklet sets out to explain how higher level skills can benefit your business. We’ll show how you, your business and workforce can benefit from work-based higher education and the various levels and types of qualification available. We’ll direct you to where you can access higher education near you and provide other useful contact addresses. What are higher level skills? “High level skills – the skills associated with higher education – are good for the individuals who acquire them and good for the economy. They help individuals unlock their talent and aspire to change their life for the better. They help businesses and public services to innovate and prosper. They help towns and cities thrive by creating jobs, helping businesses become more competitive and driving economic regeneration. High level skills add value for all of us.” Foreword, Minister of State for Lifelong Learning, Further and Higher Education ‘Higher Education at Work – High Skills: High Value’, DIUS, April 2008 Why? There are good reasons why you should consider supporting your workforce to achieve qualifications which formally recognise their skills and why those skills will improve your business opportunities: • you will be equipped with the skills needed to meet current and future challenges in line with your business needs • new ideas and business solutions can be generated by assigning employees key project work as part of their course based assignments • your commitment to staff development will increase motivation and improve recruitment and retention • skills and knowledge can be passed on and shared by employees Is it relevant to my business? Universities are keen to work with employers to ensure that courses reflect the real needs of business and industry and suit a wide range of training requirements. -

Annual Report 2019/20 Welcome Welcome

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome from Jayne Dickinson Contents Chief Executive College Group and Principal of East Surrey College Welcome .........................................................................3 It is with pride that I introduce this Annual Report as Chief Executive of Orbital South Colleges and Principal of East Surrey College. Merger on 1 February 2019, marked an important milestone for both East Meet the Team ...............................................................4 Surrey College and John Ruskin College and for local skills in our communities. This past year, it has been more important than ever to stand together to keep learning going while the pandemic has raged. And Financial Highlights ........................................................5 we certainly have. College Overview .......................................................6-7 Our brilliant staff worked tirelessly to move learning online, ensuring our students remained safe and our business intact. Working closely with schools, councils, businesses and external agencies, we kept Further Education ..........................................................8 students motivated about careers while also using the time to plan for our return to on-campus learning. A huge investment in John Ruskin College saw three brand new construction skills workshops established Higher Education ...........................................................9 over summer 2020 and a major new Construction Skills Centre opens its doors during summer 2021. Our -

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

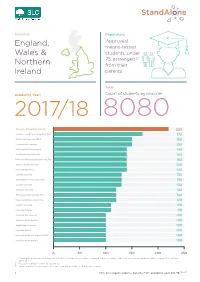

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Sealey 2003 Analysis

RADA R Oxford Brookes University – Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository (RADAR) Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. No quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. You must obtain permission for any other use of this thesis. Copies of this thesis may not be sold or offered to anyone in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright owner(s). When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Sealey, R. D. (2003). An analysis of the impact of privatisation and deregulation on the UK bus and coach and port industries. PhD thesis. Oxford Brookes University. www.brookes.ac.uk/go/radar Directorate of Learning Resources An analysis of the impact of privatisation and deregulation on the UK bus and coach and port industries Roger Derek Sealey Oxford Brookes University Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the award of Doctor of Philosophy November 2003 Acknowledgements There were many people who have assisted me this dissertation and I would like to take this opportunity of thanking them all. I would also like to thank: Eddy Batchelor, Librarian T&G Central Office; Malcolm Bee, Oxford Brookes University; Marinos Casparti, T&G Central Office; Bill Dewhurst, Ruskin College; Jim Durcan; Steve Edwards, Vice Chair, Passenger Transport Sector National Committee, T&G; -

Colleges Mergers 1993 to Date

Colleges mergers 1993 to date This spreadsheet contains details of colleges that were established under the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act and subsequently merged Sources: Learning and Skills Council, Government Education Departments, Association of Colleges College mergers under the Further Education Funding Council (FEFC) (1993-2001) Colleges Name of merged institution Local LSC area Type of merger Operative date 1 St Austell Sixth Form College and Mid-Cornwall College St Austell College Cornwall Double dissolution 02-Apr-93 Cleveland College of Further Education and Sir William Turner's Sixth 2 Cleveland Tertiary College Tees Valley Double dissolution 01-Sep-93 Form College 3 The Ridge College and Margaret Danyers College, Stockport Ridge Danyers College Greater Manchester Double dissolution 15-Aug-95 4 Acklam Sixth Form College and Kirby College of Further Education Middlesbrough College Tees Valley Double dissolution 01-Aug-95 5 Longlands College of Further Education and Marton Sixth Form College Teesside Tertiary College Tees Valley Double dissolution 01-Aug-95 St Philip's Roman Catholic Sixth Form College and South Birmingham 6 South Birmingham College Birmingham & Solihull Single dissolution (St Philips) 01-Aug-95 College North Warwickshire and Hinckley 7 Hinckley College and North Warwickshire College for Technology and Art Coventry & Warwickshire Double dissolution 01-Mar-96 College Mid-Warwickshire College and Warwickshire College for Agriculture, Warwickshire College, Royal 8 Coventry & Warwickshire Single dissolution -

Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 July 2020

REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2020 Key Management Personnel, Board of Governors and Professional advisers Key management personnel Key management personnel are defined as members of the College Leadership Team and were represented by the following in 2019/20: Mrs Jayne Dickinson - Chief Executive Officer (College Group) & Principal (ESC); Accounting Officer Mr Kevin Standish - Principal (John Ruskin College) & Quality Lead (College Group) Mrs Jyoti Baker - Chief Operating Officer (College Group) Mrs Mitzi Gibson – Executive Director HR & Professional Development (College Group) Board of Governors A full list of Governors is given on pages 18 and 19 of these financial statements. Mrs S Glover acted as Clerk to the Corporation throughout the period. Financial Statement and Regularity Auditor: Buzzacott 130 Wood Street London EC2V 6DL Internal Auditors: Scrutton Bland Fitzroy House Crown Street Ipswich, IP1 3LG Bankers: NatWest Bank Plc Barclays Bank PLC 2nd Floor Turnpike House 1 Churchill Place 123 High Street London E14 5HP Crawley, RH10 1DQ Solicitors: Mundays LLP Cedar House, 78, Portsmouth Road Cobham Surrey KT11 1AN Professional Advisors: Eversheds Buzzacott Cloth Hall Court 130 Wood Street Infirmary Street London Leeds EC2V 6DL LS1 2JB EAST SURREY COLLEGE 1 REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2020 CONTENTS Page Report of the Governing Body 3 Statement of Corporate Governance and Internal Control 17 Governing Body’s Statement on the College’s Regularity, 25 Propriety and Compliance -

Oxfordshire Directory of Training Providers September 11, 2014 Oxfordshire Directory of Training Providers

Oxfordshire Directory of Training Providers September 11, 2014 Oxfordshire Directory of Training Providers Organisations in Oxfordshire which offer foundation learning, rolling start courses, pre-apprenticeship training, work ready programmes, Traineeships, placements and other opportunities suitable for young people aged 16-19 (up to 25 if there are learning difficulties or disabilities) You can find more details about these organisations, alongside volunteering, job and apprenticeship opportunities suitable for younger job-seekers on our website at www.oxme.info/opportunities Something missing? If your organisation should be listed in this Directory, or if your details need updating, please contact [email protected] to get listed in the Directory and on the online Oxfordshire Opportunities search. Oxfordshire County Council – Youth Opportunities – www.oxme.info/opportunities Learning Providers Contents -* indicates Providers with courses for young people with additional needs Provider name Opportunity Page 3aaa - Aspire Achieve Advance All courses -3aaa Learning Provider 1 Abingdon & Witney College * All courses - Abingdon & Witney College - Learning 2 Provider ACE Training All courses -ACE - Learning Provider 3 ACE Training ACE Training - All Courses 4 Activate - City of Oxford College All courses - Activate Enterprise 5 Activate - City of Oxford College All courses - Activate Enterprise 6 Activate - Banbury & Bicester College *All courses - Banbury & Bicester College 7 Adventure Plus *All courses - Adventure Plus 8 Adviza * All courses - Adviza 9 Amersham & Wycombe College All courses - Amersham & Wycombe Training 10 Provider ATG All courses - ATG Learning Provider 11 Aylesbury College All courses - Aylesbury College - Learning Provider 12 BYHP All courses- BHYP - Learning Provider 13 Care Training Solutions All courses - Health & Social Care- Learning Provider 14 Chiltern Training Ltd. -

Higher Education Review: Ruskin College, Oxford, March 2016

Higher Education Review of Ruskin College, Oxford March 2016 Contents About this review ..................................................................................................... 1 Amended judgement - June 2017 ........................................................................... 2 Key findings .............................................................................................................. 4 QAA's judgements about Ruskin College, Oxford ................................................................. 4 Good practice ....................................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................ 4 Affirmation of action being taken ........................................................................................... 5 Theme: Student Employability ............................................................................................... 5 About Ruskin College, Oxford ................................................................................ 5 Explanation of the findings about Ruskin College, Oxford .................................. 9 1 Judgement: The maintenance of the academic standards of awards offered on behalf of degree-awarding bodies and/or other awarding organisations ....................... 10 2 Judgement: The quality of student learning opportunities ............................................. 24 3 Judgement: -

Updated February 2021 This Is Not an Exhaustive List of Post 16 Schools and Colleges

Further Education Schools and Colleges – Updated February 2021 This is not an exhaustive list of Post 16 schools and colleges, especially given the diverse needs and home addresses of our students. Please note that inclusion within this document is not an endorsement by Limpsfield Grange of the provision. We advise you to do your own careful research and to review the latest OFSTED report for each provision that you consider. Mainstream Provision School/College LA Contact Details Bromley College Bromley Tel: 020 3954 4000 Rookery Lane Email: [email protected] Bromley www.lsec.ac.uk/locations/bromley Kent BR2 8HE John Ruskin College Croydon Tel: 020 8651 1131 Selsdon Park Road Email: [email protected] South Croydon www.johnruskin.ac.uk CR2 8JJ USP College Essex Tel: 01268 756 111 (general info) or 01268 882 Seevic Campus 618 (admissions) Runnymede Chase Email: [email protected] or admissions- Benfleet [email protected] Essex SS7 1TW Farnborough College of Technology Hampshire Tel: 01252 407040 Boundary Road Email: [email protected] Farnborough www.farn-ct.ac.uk/ Hants GU14 6SB The Sixth Form College Farnborough Hampshire Tel: 01252 688200 Prospect Avenue Email: [email protected] Farnborough www.farnborough.ac.uk/ Hampshire GU14 8JX Further Education Schools and Colleges – Updated February 2021 Sparsholt College Hampshire Hampshire Tel: 01962 776441 Westley Lane Email: [email protected] Sparsholt www.sparsholt.ac.uk Winchester SO21 2NF Richard Challenor Kingston Tel: 00 8330 5947 Manor Drive North Email: New -

Oxford City Council Local Plan 2036 New Academic Or Administrative

New Academic or Oxford City Administrative Floorspace Council Local for Private Colleges and Plan 2036 Language Schools BACKGROUND PAPER 1 INTRODUCTION The success of Oxford’s economy is shaped and driven by the presence of its two universities: The world renowned University of Oxford. Ranked first in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings in 20181 the University of Oxford contributed £5.8 billion GVA and supported 50,600 jobs in the wider UK economy in 2014/15 and £2.0 billion GVA and 28,800 jobs in Oxford City2. It is the largest employer in Oxfordshire with 13,453 direct employees3 at 31 July 2016 representing 12,265 Full Time Equivalents. This figure does not include those employed solely by the colleges or by Oxford University Press, or casual workers or those employed on variable hours contracts. Oxford Brookes University is the highest placed UK institution in the 2018 QS rankings of world universities under 50 years old. It is amongst the world's top universities in 15 subjects and has earned recognition for the quality of a large number of its teaching areas4. Oxford Brookes employs 2,800 full-time equivalent staff5. At Further and Higher Education (FE/HE) level the local population is supported by the City of Oxford College which provides a wide range of vocational and academic qualifications right up to apprentice and degree level. Also at FE/HE level the independent Ruskin College, nationally one of four specialist residential colleges targeting adult NEETs (Not in Education, Employment or Training), uniquely specialises in providing educational opportunities for adults with few or no qualifications. -

Question 7 and Comments

Oxford City Council response to Inspectors initial questions Question 7 and comments July 2019 Question 7: Policies that make distinctions on the basis of the nature of the applicant The plan allows for the expansion of the two universities together with Nuffield College but Policy E3 specifically prevents any new or additional academic or administrative floor space for private colleges other than in very restrictive terms. This appears contrary to national policy in the NPPF, both in terms of its economic objective to support growth and in respect of its plan-making objective to seek opportunities to meet the development needs of their area. Moreover, by providing a framework for making planning decisions on the basis of the applicant instead of the development, it appears to apply the planning system in an unfair manner and has the potential to raise equalities concerns. If the objective is to protect housing, employment floor space and community facilities, other strong policies exist. Policy E3 appears not to be a positively-prepared policy and we are minded to recommend its deletion or significant alteration to ensure the plan is sound. The Council are invited to comment. By specifically applying Policy V7 to state schools the Plan appears to take the same approach towards favouring one applicant over another; in any case the existence of different types of school make it difficult to make such a distinction. We are minded to recommend the deletion of the word “state”. The Council are invited to comment. Evidence and justification for Policy E3 Meeting the development needs of the area 7.1 This policy is fundamentally linked to the wider employment strategy to maximise land availability for B1 uses and other uses fundamental to delivering the knowledge economy within the city. -

Exeter College Register 2019

EXETER COLLEGE REGISTER 2019 Cover image of Exeter College by Ian Fraser is available as a print from www.vaprints.co.uk Contents From the Rector 2 From the President of the MCR 9 From the Chaplain 11 From the Librarian and the Archivist 14 Departing Fellows 22 Obituaries 29 Rector’s Seminars 43 Tolkien, The Movie – a linguistic response 46 Student Activities 51 ‘The famous orationer that has publish’d the book’: Printed Lectures on Elocution 55 The Governing Body 63 Honorary Fellows 64 Emeritus Fellows 66 Honours, Appointments, and Awards 68 Publications Reported 69 The College Staff 71 Class Lists in Honour Schools 76 Distinctions in Preliminary Examinations, and Frist Class in Moderations 79 Graduate Degrees 80 University, College, and Other Prizes 85 Major Scholarships, Studentships, and Bursaries 87 Graduate Freshers 92 Undergraduate Freshers 96 Visiting Students 103 Births, Marriages, Civil Partnerships, and Deaths 104 Notices 107 Contributors 108 1 From the Rector In June the Governing Body finalised Exeter’s new Strategic Plan, for the years 2019-2029. The new Plan is only the College’s second. The first, approved in 2008, identified an acute shortage of space as a major strategic problem. Fuelled in part by large numbers of alumni donations, Cohen Quadrangle – opened in 2017 and now the recipient of the first prize in the Higher Education and Research category at the World Architecture Festival – splendidly filled that gap. The new plan uses Cohen Quad as a springboard for further achievement in four major dimensions: diversity, excellence, stewardship (including sustainability) and community. Prioritised by Exeter’s Strategy Group, projects identified by Governing Body in June will implement these themes in five major areas of activity: the undergraduate experience; the postgraduate experience; Fellows, staff and governance; connections within and beyond College; and resources & stewardship (including buildings and infrastructure).