Round Table Conference 2000 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

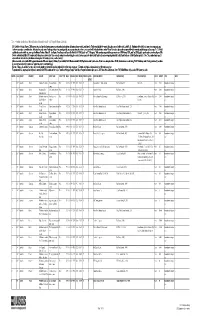

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Our Minerals and Mining Capabilities

KAURNA ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We acknowledge and pay our respects to the Kaurna Just as the minerals sector is central to our nation’s identity people, the original custodians of the Adelaide Plains and prosperity, so it is to the University of Adelaide. and the land on which the University of Adelaide’s Through our world-class research and development campuses at North Terrace, Waite, and Roseworthy expertise, we’ve supported and strengthened Australian are built. We acknowledge the deep feelings of WELCOME attachment and relationship of the Kaurna people mining since 1889; and we will continue to act as a catalyst to country and we respect and value their past, for its success well into the future. present and ongoing connection to the land and As you’ll see in these pages, our relevant expertise and cultural beliefs. The University continues to develop experience—coordinated and focused through our Institute respectful and reciprocal relationships with all for Mineral and Energy Resources—encompasses every Indigenous peoples in Australia, and with other Indigenous peoples throughout the world. aspect of the minerals value chain. You will also see evidenced here the high value we place on industry collaboration. We believe strong, productive partnerships are essential, both to address the sector’s biggest challenges and maximise its greatest opportunities. An exciting tomorrow is there for the making—more efficient, more productive and environmentally sustainable. We would welcome the chance to shape it with you. Regards, Professor Peter Høj -

Application Accepted

Applications Accepted On 5 July 2006 Matching for 'Applications Accepted' during July 2006. IPMonitorTrademarks www.ipmonitor.com.au Contents Alerts 3 1 event 3 Terms and Conditions 31 General 31 Disclaimer of warranty and limitation of liability 31 Copyright 31 Arbitration 31 www.ipmonitor.com.au Alerts 1 event More than 500 results matching for 'Applications Accepted' during July 2006. Number Mark Owner Date 948956 Bear Factory Limited 05 Jul 2006 962643 HOME VALUE HSBC Bank Australia Limited 05 Jul 2006 ACN/ARBN 006 434 162 963086 EasyPoint NCR Corporation a Maryland corporation 05 Jul 2006 965450 Hemmes Trading Pty Limited ACN/ARBN 05 Jul 2006 105 332 652 968791 AGL GREEN ENERGY The Australian Gas Light Co. 05 Jul 2006 979069 THROMBIN-JMI King Pharmaceuticals Research and 05 Jul 2006 Development, Inc. 982443 YOUR PLATINUM CONNECTION Commonwealth Bank 05 Jul 2006 989217 SGS Societe Generale de Surveillance IP 05 Jul 2006 SA 990000 RECLAIM Victoria Principal Productions Inc a 05 Jul 2006 California corporation 990920 PERFORMANCE PACK Bayer Australia Ltd 05 Jul 2006 992342 STANDARD 3748 William Adams Pty Ltd 05 Jul 2006 995537 ERNIE ELS Blue Ocean Trademarks NV 05 Jul 2006 1005358 QFLEET Crown in Right 05 Jul 2006 1012246 Hardware Supply Pty Ltd 05 Jul 2006 1012505 OPEN SESAME Sesame Workshop 05 Jul 2006 1014545 AQUAPURA Bickford's Australia Pty Ltd ACN/ARBN 05 Jul 2006 053 240 261 1014800 The Daily Briefing Sanderson, Wayne 05 Jul 2006 1016240 SALTWATER WINE Saltwater Wine Surf Centres Pty Ltd 05 Jul 2006 1019006 Medicap Dixon, Barry James. 05 Jul 2006 1024445 PROSCIUTTO DI PARMA Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma 05 Jul 2006 www.ipmonitor.com.au 3 of 31 Number Mark Owner Date 1024579 F. -

The Mineral Industry of Australia in 2008

2008 Minerals Yearbook AUSTRALIA U.S. Department of the Interior August 2010 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUS T RY OF AUS T RALIA By Pui-Kwan Tse Australia was one of the world’s leading mineral producing and the Brockman iron project in the Pilbara region of Western countries and ranked among the top 10 countries in the world Australia (Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource in the production of bauxite, coal, cobalt, copper, gem and Economics, 2009a). near-gem diamond, gold, iron ore, lithium, manganese ore, tantalum, and uranium. Since mid-2008, the global financial Minerals in the National Economy crisis had sharply weakened world economic activities, and the slowdown had been particularly pronounced in the developed Australia’s mining sector contributed more than $105 billion countries in the West. Emerging Asian economies were also to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), or 7.7% of the adversely affected by the sharply weaker demand for exports GDP during fiscal year 2007-08. In 2008, the mining sector and tighter credit conditions. After a period of strong expansion, employed 173,900 people who worked directly in mining and an Australia’s economic growth decreased by 0.5% in the final additional 200,000 who were involved in supporting the mining quarter of 2008. Overall, Australia’s economy grew at a rate activities. Expectations of sustained levels of global demand for of 2.4% during 2008. During the past several years, owing to minerals led to increased production of minerals and metals in anticipated higher prices of mineral commodities in the world Australia, and the mineral industry was expected to continue markets, Australia’s mineral commodity output capacities to be a major contributor to the Australian economy in the next expanded rapidly. -

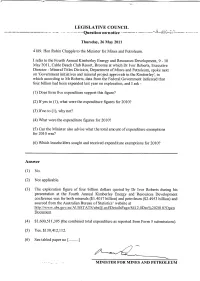

2011-08-09 Qon Exploration Expenditure

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL C 'lff"\ 1"'.( "''1 ---------~~-~Question- on"notice ----------- ..'-?ibt;-:s::'.;"--- --_.- Thursday, 26 May 2011 4189. Hon Robin Chapple to the Minister for Mines and Petroleum. I refer to the Fourth Annual Kimberley Energy and Resources Development, 9 - 10 May 2011, Cable Beach Club Resort, Broome at which Dr Ivor Roberts, Executive Director - Mineral Titles Division, Department of Mines and Petroleum, spoke next on 'Government initiatives and mineral project approvals in the Kimberley', in which according to Mr Roberts, data from the Federal Government indicated that four billion had been expended last year on exploration, and 1 ask - (1) Does form five expenditure support this figure? (2) If yes to (1), what were the expenditure figures for 201O? (3) Ifno to (1), why not? (4) What were the expenditure figures for 2010? (5) Can the Minister also advise what the total amount of expenditure exemptions for 2010 was? (6) Which leaseholders sought and received expenditure exemptions for 2010? Answer (1) No. (2) Not applicable. (3) The exploration figure of four billion dollars quoted by Dr Ivor Roberts during his presentation at the Fourth Annual Kimberley Energy and Resources Development conference was for both minerals ($1.4017 billion) and petroleum ($2.4953 billion) and sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics' website at http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSST ATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/8412.0Dec%20201 O?Open Document (4) $1,600,511,395 (the combined total expenditure as reported from Form 5 submissions). (5) Yes, $130,412,112. -

The Author Is Available on 0408 802 212 to Answer Any Queries

NAVIGATION *Unfortunately, the product’s efficient navigation system with the index to the left of screen cannot be contained in this preview. Just use the scroll mechanism to the right and make sure you see the incredible depth of this publication by perusing the Index at p. 3. UPDATE TO OCTOBER 2014 Index - Keyword headings Index - Legislative Links Index - Fair Work Act sections 1994 Index - Fair Work Act Commonwealth sections Index - Fair Work (General) Regulations 2009 Index - Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 Index - Fair Work Act Rules 2010 Index - Fair Work (Transitional Provisions …) Act 2009 Index - Industrial Proceeding Rules Index - Long Service Leave Act 1997 Index - Occupational Health Safety & Welfare Act 1998 Repealed Index - Work Health and Safety Legislation (National Scheme) This guide aims to point the subscriber to all the relevant cases, and to provide helpful 'judicial' commentary stating the general principles, but it is no substitute for carefully researched legal consideration or advice. The author is available on 0408 802 212 to answer any queries. Every effort has been and will be made to keep the statements of law contained herein up-to-date, but please be careful to check the latest legislation and decisions yourself before relying on an older decision. I thank my assistants Patricia Lee and Mark Nemstas for their assistance in the preparation of the Hardcover Loose Leaf and Web versions. © 2014 Kidd LRS Pty Ltd This guide is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced or copied by any process, electronic or otherwise (including photocopying, recording, taping) without specific written permission of Kidd LRS Pty Ltd. -

Adelaide Brighton Ltd ACN 007 596 018

Level 1 Telephone (08) 8223 8000 157 Grenfell Street International +618 8223 8000 Adelaide SA 5000 Facsimile (08) 8215 0030 GPO Box 2155 www.adbri.com.au Adelaide SA 5001 Adelaide Brighton Ltd ACN 007 596 018 21 April 2016 The Manager ASX Market Announcements Australian Securities Exchange Limited Exchange Centre 20 Bridge Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Sir/Madam We attach the 2015 Adelaide Brighton Ltd Annual Report which will be dispatched to shareholders today. Yours faithfully Marcus Clayton Company Secretary Adelaide Brighton Ltd Annual Report 2015 Company profile Adelaide Brighton is a leading integrated construction materials 1 Performance summary and industrial lime producer which supplies a range of products 2 Chairman’s report into building, construction, infrastructure and mineral processing 4 Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer review markets throughout Australia. The Company’s principal activities 8 Finance report include the production, importation, distribution and marketing 10 Map of operations of clinker, cement, industrial lime, premixed concrete, construction 11 Review of operations aggregates and concrete products. Adelaide Brighton originated 12 Cement and Lime in 1882 and is now an S&P/ASX100 company with 1,400 employees 14 Concrete and Aggregates and operations in all Australian states and territories. 16 Concrete Products 18 Joint ventures Cement 19 Sustainability Adelaide Brighton is the second largest supplier of cement and 20 Sustainability report clinker products in Australia with major production facilities and 25 People, health and safety market leading positions in the resource rich states of South 28 Directors Australia and Western Australia. It is also market leader in the 30 Diversity report Northern Territory. -

Listing of Transactions by Source Country

September 1986 APPENDIX B LIST OF INVESTMENT TRANSACTIONS by SOURCE COUNTRY - 83 - Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis September 1986 1985 FOREIGN INVESTMENTS COMPLETED TRANSACTIONS NA US FIRM NAME LOCATION TS SIC FOREIGN INVESTOR TY VALUE AS ASARCO INC. NEW YORK NY 3331 M.I.M. HOLDINGS LTD. El 97 7 AS AUSTEC INC. SAN JOSE CA 7372 AUSTEC PTY LTD OT AS AVALON CORP. NEW YORK NY 1382 MOONIE OIL CO., THE El 0 1 AS BALFOURS USA NASHVILLE TN 3551 BALFOUR WAUCHOPE PTY LTD. OT AS BAXTER'S SURGICAL GLOVE PLANT AZ 3069 DUNLOP OLYMPIC LTD. AM AS BEKINS EXPRESS AIR FREIGHT UNIT GLENDALE CA 4511 THOMAS NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT LTD. AM AS DATA CABLE CA 5051 DATA CABLE OT AS EARTH ENERGY INC. TX 1311 KRATOS MINERALS NL AM 4 0 AS HARKEN OIL & GAS INC. ABILENE TX 1311 QUASHA, PHYLLIS El 0 1 AS KAISERS NANAKULI CEMENT PLT HI 3241 ADELAIDE BRIGHTON CEMENT HOLDINGS AM AS LONE STAR INDS. SO TX PLANT TX 3241 PIONEER CONCRETE SERVICES LTD. AM 20 0 AS MONSANTO OIL CO'S ASSETS HOUSTON TX 1311 HOLMES A COURT, ROBERT AM 745 0 AS MOSEMAN CONTRUCTION CO. REDDING CA 1622 HOLLAND GROUP AM AS NATIONAL CONTROLS INC. SANTA ROSA CA 3576 PAUL RAMSAY HOSPITALS AM AS PROUDS USA GA 5961 HOOKER CORP. OT 0 3 AU AUTOMATED MEDICAL LABS. INC. HIALEAH FL 8081 IMMUNO INTL AG AM 2 8 AU CHAMPION INTERNATIONAL CORP'S DIVISION MA 2641 ZELLSTOFF-UND PAPIERFABRIK FRANT. AG AM BA ARAPAHO PETROLEUM INC. -

Adelaide Brighton Ltd 2014 Annual Report

Adelaide Brighton Ltd 2014 Annual Report Company profile Adelaide Brighton is a leading integrated construction materials and lime producer 1 Performance summary which supplies a range of products into building, construction, infrastructure and 2 Chairman’s Report mineral processing markets throughout Australia. The Company’s principal activities 4 Chief Executive Officer’s Report include the production, importation, distribution and marketing of clinker, cement, 8 Finance Report industrial lime, premixed concrete, construction aggregates and concrete products. 10 Map of operations Adelaide Brighton originated in 1882 and is now an S&P/ASX100 company with 11 Review of operations 1,400 employees and operations in all Australian states and territories. 12 Cement and Lime 14 Concrete and Aggregates Cement 16 Concrete Products 18 Joint ventures Adelaide Brighton is the second largest supplier of cement and clinker products in 19 Sustainability Australia with major production facilities and market leading positions in the resource 20 Sustainability Report rich states of South Australia and Western Australia. It is also market leader in the 25 People, health and safety Northern Territory. In addition to domestic production, the Company is the largest 27 Corporate governance statement importer of cement, clinker and slag into Australia with an unmatched supply network 34 Diversity report that enables efficient access to every mainland capital city market. This network 36 Directors includes significant distribution joint ventures in Victoria and Queensland. 37 Financial statements index 38 Directors’ report Lime 45 Remuneration report introductory letter Adelaide Brighton is the largest producer of lime in Australia, with production assets 46 Remuneration report contents in Western Australia, South Australia and Northern Territory. -

The Association Between Air Pollution and Lung Cancer in the North West of Adelaide

The association between air pollution and lung cancer in the North West of Adelaide: a case control study and air quality monitoring Melissa Jayne Whitrow Department of Medicine and Department of Public Health Faculty of Health Science The University of Adelaide July 2004 Table of Contents 1. Chapter 1 Introduction..............................................................................................25 1.1. Lung Cancer...........................................................................................................29 1.1.1. Lung Cancer Demographics...........................................................................29 1.1.2. Lung Cancer in Australia...............................................................................33 1.1.3. Aetiology........................................................................................................37 1.2. North Western Metropolitan Adelaide................................................................38 1.2.1. Lung Cancer in the North West......................................................................40 1.2.2. Industry in the North West.............................................................................40 1.2.3. Ambient Air Quality in the NW.....................................................................49 2. Chapter 2 Review of the Literature..........................................................................51 2.1. Lung Cancer Histology..........................................................................................52 2.1.1. -

The Mineral Industry of Australia in 2011

2011 Minerals Yearbook AUSTRALIA U.S. Department of the Interior September 2013 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF AUSTRALIA By Pui-Kwan Tse Slow growth in the economies of the Western developed Minerals in the National Economy countries in 2011 negatively affected economic growth in many counties of the Asia and the Pacific region. China Australia’s mineral sector contributed more than $100 billion, continued to have rapid economic growth in the first part of or about 8%, to the country’s GDP in 2011. The mineral sector the year and helped to sustain demand for Australia’s mineral employed 205,000 people. Expectations of sustained levels products. By mid-2011, however, China’s economic growth of global demand for minerals led to increased production of had moderated. Also, extreme weather conditions across the minerals and metals in Australia, and the mineral industry was States of Queensland, Victoria, and part of New South Wales expected to continue to be a major contributor to the Australian caused disruptions to regional economic activities in the economy in the next several years (Australian Bureau of first quarter of 2011. As a result, Australia’s gross domestic Resources and Energy Economics, 2012b, p. 12). product (GDP) increased at a rate of 2.3% during 2011, which Government Policies and Programs was lower than the 2.7% recorded in 2010. The lower annual growth rate was attributed to weaker export growth, including The powers of Australia’s Commonwealth Government are in the mineral sector. Australia was one of the world’s leading defined in the Australian Constitution; powers not defined in the mineral-producing countries and ranked among the top 10 Constitution belong to the States and Territories. -

Kenneth (Ken) Sidebottom Managing Director and CEO

Précis – Kenneth (Ken) Sidebottom Managing Director and CEO Ken has over thirty years of successful consulting and change management experience in executive management, general management and Board level advisory. He worked in the private sector to the level of Divisional General Manager with Pioneer International Ltd, where he was very successful building capability, increasing quality, customer service focus and profitability in the concrete, quarrying and transport operations he managed. He then completed a transition into professional services consulting, where he partnered with Boards and executive management, throughout his program management and business improvement facilitation roles to create an enviable record of successful sustainable implementation. He has served as a Director of several companies including Pioneer Concrete NSW Pty Ltd, MAXX Operational Management Pty Ltd and Simsworx Pty Ltd. In his recent role as Principal Consultant he had responsibility for all analysis’s, project setup, training and project delivery in Australia, New Zealand and South East Asia. His particular skills and passionate interest are in creating capability that is sustainable in executive management, positively engaging stakeholders to develop agreed strategic vision and implementation of blue prints for the future; coaching and training managers; problem solving; business analysis; process re-engineering and facilitation of organisational change. For the past 5 years Ken has been Principal Consultant for Simsworx Pty Ltd and is continuing his professional career in Business Improvement and Management advisory professional consulting services with Simsworx; where he will grasp opportunities in organisations that require strong stewardship, training, coaching, mentoring and facilitation, that achieves sustainable improvement through building capability and high performing individuals and teams that successfully implement sustainable future solutions and outcomes.