Usufruct: General Principles - Louisiana and Comparative Law A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised Or Amended in 2005)

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised or Amended in 2005) drafted by the NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS and by it APPROVED AND RECOMMENDED FOR ENACTMENT IN ALL THE STATES at its ANNUAL CONFERENCE MEETING IN ITS ONE-HUNDRED-AND-THIRTEENTH YEAR PORTLAND, OREGON JULY 30-AUGUST 6, 2004 WITH PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS Copyright ©2004 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS April 2005 ABOUT NCCUSL The National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), now in its 114th year, provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law. Conference members must be lawyers, qualified to practice law. They are practicing lawyers, judges, legislators and legislative staff and law professors, who have been appointed by state governments as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to research, draft and promote enactment of uniform state laws in areas of state law where uniformity is desirable and practical. • NCCUSL strengthens the federal system by providing rules and procedures that are consistent from state to state but that also reflect the diverse experience of the states. • NCCUSL statutes are representative of state experience, because the organization is made up of representatives from each state, appointed by state government. • NCCUSL keeps state law up-to-date by addressing important and timely legal issues. • NCCUSL’s efforts reduce the need for individuals and businesses to deal with different laws as they move and do business in different states. -

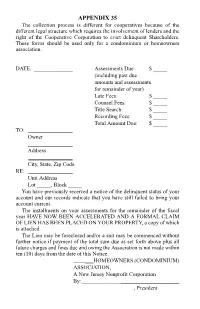

35. Notice of Acceleration of Assessment and Filing of Lien; Claim of Lien

APPENDIX 35 The collection process is different for cooperatives because of the different legal structure which requires the involvement of lenders and the right of the Cooperative Corporation to evict delinquent Shareholders. These forms should be used only for a condominium or homeowners association. DATE: ______________ Assessments Due: $ _____ (including past due amounts and assessments for remainder of year) Late Fees: $ _____ Counsel Fees: $ _____ Title Search: $ _____ Recording Fees: $ _____ Total Amount Due: $ _____ TO: ________________ Owner ________________ Address ________________ City, State, Zip Code RE: ________________ Unit Address Lot _____, Block _____ You have previously received a notice of the delinquent status of your account and our records indicate that you have still failed to bring your account current. The installments on your assessments for the remainder of the fiscal year HAVE NOW BEEN ACCELERATED AND A FORMAL CLAIM OF LIEN HAS BEEN PLACED ON YOUR PROPERTY, a copy of which is attached. The Lien may be foreclosed and/or a suit may be commenced without further notice if payment of the total sum due as set forth above plus all future charges and fines due and owing the Association is not made within ten (10) days from the date of this Notice. ___HOMEOWNERS (CONDOMINIUM) ASSOCIATION, A New Jersey Nonprofit Corporation By: _____________________ , President CLAIM OF LIEN CLAIM OF LIEN _________ Homeowners (Condominium) Association, Inc., a New Jersey nonprofit corporation (“Association”), with an address at , , New Jersey, , in care of (Management Company) , hereby claims a lien for unpaid assessments, charges and expenses in accordance with the terms of that certain Declaration of Covenants and Restrictions (“Declaration”) or Master Deed (“Master Deed”) for _______ recorded on in the County Clerk's Office in Deed Book Page et seq. -

G.S. 45-36.24 Page 1 § 45-36.24. Expiration of Lien of Security

§ 45-36.24. Expiration of lien of security instrument. (a) Maturity Date. – For purposes of this section: (1) If a secured obligation is for the payment of money: a. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on a date specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If no such date is specified in the secured obligation, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation. b. If all remaining sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand or on a date specified in the secured obligation, whichever first occurs, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date so specified. If all sums owing on the secured obligation are due and payable in full on demand and no alternative date is specified in the secured obligation for payment in full, the maturity date of the secured obligation is the date of the secured obligation. c. The maturity date of the secured obligation is "stated" in a security instrument if (i) the maturity date of the secured obligation is specified as a date certain in the security instrument, (ii) the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation is specified in the security instrument, or (iii) the maturity date of the secured obligation or the last date a payment on the secured obligation is due and payable under the terms of the secured obligation can be ascertained or determined from information contained in the security instrument, such as, for example, from a payment schedule contained in the security instrument. -

Deed Recording

DEED RECORDING Deeds are important legal documents. The Onondaga County Clerk’s Office strongly recommends consulting an attorney regarding the preparation and filing/recording of any legal document. OUR OFFICE IS PROHIBITED BY LAW FROM PROVIDING ANY LEGAL ADVCE. THE ACCEPTANCE OF AN INSTRUMENT FOR RECORDING IN NO WAY IMPLIES AN ENDORSEMENT OR LEGAL SUFFICIENCY OR A GUARANTEE OF TITLE. IF YOU CHOOSE TO ACT AS YOUR OWN ATTORNEY YOU ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR LEGAL COMPLIANCE AND ANY IMPLICATIONS THEREOF. To find a local attorney who specializes in real estate, contact the Onondaga County Bar Association Lawyer Referral Serve at 315.471.2690. Their website is located at https://www.onbar.org/ Our office does not supply forms. To purchase a New York State specific deed form, you may visit the Blumberg Legal Forms website at: https://www.blumberg.com/forms/ All deed filings must be accompanied by both an RP-5217 and TP 584 All recording in Onondaga County require a legal description for the subject property. ADDITIONAL RECORDING FEE EFFECTIVE MARCH 11, 2020 Effective March 11, 2020 there will be a $10 fee added to all residential deed recordings. On January 11, 2020 Governor Cuomo signed into law an amendment to Real Property Law Section 291 that requires County Clerks to notify the owner(s) of record of residential real property when a document is recorded affecting said residential property. The law also allows a reasonable fee to be assessed for said notices. The NYS Association of County Clerks, in order to provide uniformity throughout NYS, has determined that $10 is a reasonable fee per document. -

Bundle of S Cks—Real Property Rights and Title Insurance Coverage

Bundle of Scks—Real Property Rights and Title Insurance Coverage Marc Israel, Esq. What Does Title Insurance “Insure”? • Title is Vested in Named Insured • Title is Free of Liens and Encumbrances • Title is Marketable • Full Legal Use and Access to Property Real Property Defined All land, structures, fixtures, anything growing on the land, and all interests in the property, which may include the right to future ownership (remainder), right to occupy for a period of +me (tenancy or life estate), the right to build up (airspace) and drill down (minerals), the right to get the property back (reversion), or an easement across another's property.” Bundle of Scks—Start with Fee Simple Absolute • Fee Simple Absolute • The Greatest Possible Rights Insured by ALTA 2006 Policy • “The greatest possible estate in land, wherein the owner has the right to use it, exclusively possess it, improve it, dispose of it by deed or will, and take its fruits.” Fee Simple—Lots of Rights • Includes Right to: • Occupy (ALTA 2006) • Use (ALTA 2006) • Lease (Schedule B-Rights of Tenants) • Mortgage (Schedule B-Mortgage) • Subdivide (Subject to Zoning—Insurable in Certain States) • Create a Covenant Running with the Land (Schedule B) • Dispose Life Estate S+ck • Life Estate to Person to Occupy for His Life+me • Life Estate can be Conveyed but Only for the Original Grantee’s Lifeme • Remainderman—Defined in Deed • Right of Reversion—Defined in Deed S+cks Above, On and Below the Ground • Subsurface Rights • Drilling, Removing Minerals • Grazing Rights • Air Rights (Not Development Rights—TDRs) • Canlever Over a Property • Subject to FAA Rules NYC Air Rights –Actually Development Rights • Development Rights are not Real Property • Purely Statutory Rights • Transferrable Development Rights (TDRs) Under the NYC Zoning Resoluon and Department of Buildings Rules • Not Insurable as They are Not Real Property Title Insurance on NYC “Air Rights” • Easement is an Insurable Real Property Interest • Easement for Light and Air Gives the Owner of the Merged Lots Ability to Insure. -

Title Matters Affecting Parties in Possession: By

TITLE MATTERS AFFECTING PARTIES IN POSSESSION: ADVERSE POSSESSION, AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE, & THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES BY DONALD G. SINEX SCOTT C. PETRY SUSAN A. STANTON TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 I. ADVERSE POSSESSION…….……………………………………………………………. 1 1. Adverse Possession………...………………...……………………………………….......... 2 2. Identifying Issues in Record Title…………………………………………………………. 3 a. Historical Changes in Metes and Bounds…………………………………………… 4 b. Adverse Possession of Minerals……………………………………………………… 4 c. Adverse Possession in Cotenancy, Landlord-Tenant, & Grantor-Grantee Situations………………………………………………………………………….…...... 5 d. Distinguishing Coholders from Cotenants………………………………………….. 6 3. Adverse Possession Requirement………………………………………………………… 7 4. Other Issues………………………………………...……………………………………….. 9 II. AFTER ACQUIRED TITLE………………………….…………………………………………. 10 1. The Doctrine………………..……... ……………………………………………………….. 10 2. Bases Used by Courts in Applying the Doctrine…………………………………........... 11 3. Conveyance Instruments that an Examiner is Likely to Encounter…………………… 12 a. Deeds of Trust and Liens……………………………………………………………... 12 b. Oil & Gas Leases and Limitations……………………………………………………. 14 c. Public Lands……………………………………………………………………………. 15 d. Title Acquired in Trust………………………………………………………………… 16 e. Quitclaims and Limitations…………………………………………………………… 16 4. Effect on Notice and Purchasers………………………………………………………….. 18 a. Subsequent Purchaser…………………………………………………………………. 19 b. Protections……………………………………...………………………………………. 19 c. Duty to Search…………………………………………………………………………. -

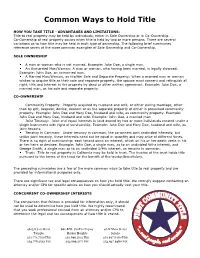

Common Ways to Hold Title

Common Ways to Hold Title HOW YOU TAKE TITLE - ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS: Title to real property may be held by individuals, either in Sole Ownership or in Co-Ownership. Co-Ownership of real property occurs when title is held by two or more persons. There are several variations as to how title may be held in each type of ownership. The following brief summaries reference seven of the more common examples of Sole Ownership and Co-Ownership. SOLE OWNERSHIP A man or woman who is not married. Example: John Doe, a single man. An Unmarried Man/Woman: A man or woman, who having been married, is legally divorced. Example: John Doe, an unmarried man. A Married Man/Woman, as His/Her Sole and Separate Property: When a married man or woman wishes to acquire title as their sole and separate property, the spouse must consent and relinquish all right, title and interest in the property by deed or other written agreement. Example: John Doe, a married man, as his sole and separate property. CO-OWNERSHIP Community Property: Property acquired by husband and wife, or either during marriage, other than by gift, bequest, devise, descent or as the separate property of either is presumed community property. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife, as community property. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife. Example: John Doe, a married man Joint Tenancy: Joint and equal interests in land owned by two or more individuals created under a single instrument with right of survivorship. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife, as joint tenants. -

Common Ways of Holding Title to Real Property

NORTH AMERICAN TITLE COMPANY Common Ways of Holding Title to Real Property Tenancy in Common Joint Tenancy Parties Any number of persons. Any number of persons. (Can be husband and wife) (Can be husband and wife) Division Ownership can be divided into any number of Ownership interests cannot be divided. interests, equal or unequal. Title Each co-owner has a separate legal title to his There is only one title to the entire property. undivided interest. Possession Equal right of possession. Equal right of possession. Conveyance Each co-owner’s interest may be conveyed Conveyance by one co-owner without the separately by its owner. others breaks the joint tenancy. Purchaser’s Status Purchaser becomes a tenant in common with Purchaser becomes a tenant in common with other co-owners. other co-owners. Death On co-owner’s death, his interest passes by On co-owner’s death, his interest ends and will or intestate succession to his devisees or cannot be willed. Surviving joint tenants heirs. No survivorship right. own the property by survivorship. Successor’s Status Devisees or heirs become tenants in common. Last survivor owns property in severalty. Creditor’s Rights Co-owner’s interest may be sold on execution Co-owner’s interest may be sold on execu- sale to satisfy his creditor. Creditor becomes a tion sale to satisfy creditor. Joint tenancy is tenant in common. broken, creditor becomes tenant in common. Presumption Favored in doubtful cases. None. Must be expressly declared. This is provided for informational puposes only. Specific questions for actual real property transactions should be directed to your attorney or C.P.A. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

Property Ownership for Women Enriches, Empowers and Protects

ICRW Millennium Development Goals Series PROPERTY OWNERSHIP FOR WOMEN ENRICHES, EMPOWERS AND PROTECTS Toward Achieving the Third Millennium Development Goal to Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women It is widely recognized that if women are to improve their lives and escape poverty, they need the appropriate skills and tools to do so. Yet women in many countries are far less likely than men to own property and otherwise control assets—key tools to gaining eco- nomic security and earning higher incomes. Women’s lack of property ownership is important because it contributes to women’s low social status and their vulnerability to poverty. It also increasingly is linked to development-related problems, including HIV and AIDS, hunger, urbanization, migration, and domestic violence. Women who do not own property are far less likely to take economic risks and realize their full economic potential. The international community and policymakers increasingly are aware that guaranteeing women’s property and inheritance rights must be part of any development agenda. But no single global blueprint can address the complex landscape of property and inheritance practices—practices that are country- and culture-specific. For international development efforts to succeed—be they focused on reducing poverty broadly or empowering women purposely—women need effective land and housing rights as well as equal access to credit, technical information and other inputs. ENRICH, EMPOWER, PROTECT Women who own property or otherwise con- and tools—assets taken trol assets are better positioned to improve away when these women their lives and cope should they experience and their children need them most. -

UC Berkeley Working Papers

UC Berkeley Working Papers Title Locality and custom : non-aboriginal claims to customary usufructuary rights as a source of rural protest Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9jf7737p Author Fortmann, Louise Publication Date 1988 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California % LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTEST Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley !mmUTE OF STUDIES'l NOV 1 1988 Of Working Paper 88-27 INSTITUTE OF GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTEST Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley Working Paper 88-27 November 1988 Institute of Governmental Studies Berkeley, CA 94720 Working Papers published by the Institute of Governmental Studies provide quick dissemination of draft reports and papers, preliminary analyses, and papers with a limited audience. The objective is to assist authors in refining their ideas by circulating research results ana to stimulate discussion about puolic policy. Working Papers are reproduced unedited directly from the author's pages. LOCALITY AND CUSTOM: NON-ABORIGINAL CLAIMS TO CUSTOMARY USUFRUCTUARY RIGHTS AS A SOURCE OF RURAL PROTESTi Louise Fortmann Department of Forestry and Resource Management University of California at Berkeley Between 1983 and 1986, Adamsville, a small mountain community surrounded by national forest, was the site of three protests. In the first, the Woodcutters' Rebellion, local residents protested the imposition of a fee for cutting firewood on national forest land. -

Anatomy of a Will

PRESENTED AT 18th Annual Estate Planning, Guardianship and Elder Law Conference August 11‐12, 2016 Galveston, Texas ANATOMY OF A WILL Bernard E. ("Barney") Jones Author Contact Information: Bernard E. ("Barney") Jones Attorney at Law 3555 Timmons Lane, Suite 1020 Houston, Texas 77027 713‐621‐3330 Fax 713‐621‐6009 [email protected] The University of Texas School of Law Continuing Legal Education ▪ 512.475.6700 ▪ utcle.org Bernard E. (“Barney”) Jones Attorney at Law 3555 Timmons Lane, Suite 1020 • Houston, Texas 77027 • 713.621.3330 • fax 832.201.9219 • [email protected] Professional ! Board Certified, Estate Planning and Probate Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization (since 1991) ! Fellow, American College of Trust and Estate Council (elected 1995) ! Adjunct Professor of Law (former), University of Houston Law Center, Houston, Texas, 1995 - 2001 (course: Estate Planning) ! Texas Bar Section on Real Estate, Probate and Trust Law " Council Member, 1998 - 2002; Grantor Trust Committee Chair, 1999 - 2002; Community Property Committee Chair, 1999 - 2002; Subcommittee on Revocable Trusts chair, 1993 - 94 " Subcommittee on Transmutation, member, 1995 - 99, and principal author of statute and constitutional amendment enabling "conversions to community" Education University of Texas, Austin, Texas; J.D., with honors, May 1983; B.A., with honors, May 1980 Selected Speeches, Publications, etc. ! Drafting Down (KISS Revisited) - The Utility and Fallacy of Simplified Estate Planning, 20th Annual State Bar of Texas Advanced Drafting: Estate Planning