Dance & Costumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Incorporare Il Fantastico: Marie Taglioni Elena Cervellati ([email protected])

* Incorporare il fantastico: Marie Taglioni Elena Cervellati ([email protected]) Il balletto fantastico e Marie Taglioni Negli anni Trenta dell'Ottocento in alcuni grandi teatri istituzionali europei fioriscono balletti in grado di raccogliere e fare precipitare in una forma visibile istanze che percorrono, proprio in quegli anni, diversi ambiti della cultura, della società, del sentire, consolidando e facendo diventare norma un certo modo di trovare temi e personaggi, di strutturare tessuti drammaturgici, di costruire il mondo in cui l'azione si svolgerà, di danzare. Mondi altri con cui chi vive sulla terra può entrare in relazione, passaggi dallo stato di veglia a sogni densi di avvenimenti, incantesimi e malefici, esseri fatti di nebbia e di luce, ombre e spiriti impalpabili, creature volanti, esseri umani che assumono sembianze animali, oggetti inanimati che prendono vita e forme antropomorfe trovano nello spettacolo coreico e nel corpo danzante di quegli anni un luogo di elezione, andando a costituire uno dei tratti fondamentali del balletto romantico. Il danzatore abita i mondi proposti dalla “magnifica evasione” 1 offerta dal balletto e ne è al tempo stesso creatore primo. È capace di azioni sorprendenti, analoghe a quelle dell’acrobata che “poursuit sa propre perfection à travers la réussite de l’acte prodigieux qui met en valeur toutes les ressources de son corps”2. Lo stesso corpo * Il presente saggio è in corso di pubblicazione in Pasqualicchio, Nicola (a cura di), La meraviglia e la paura. Il fantastico nel teatro europeo (1750-1950) , atti del convegno, Università degli Studi di Verona, Verona, 10-11 marzo 2011. 1 Susan Leigh Foster, Coreografia e narrazione , Roma, Dino Audino Editore, 2003, p. -

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

Romantic Ballet

ROMANTIC BALLET FANNY ELLSLER, 1810 - 1884 SHE ARRIVED ON SCENE IN 1834, VIENNESE BY BIRTH, AND WAS A PASSIONATE DANCER. A RIVALRY BETWEEN TAGLIONI AND HER ENSUED. THE DIRECTOR OF THE PARIS OPERA DELIBERATELY INTRODUCED AND PROMOTED ELLSLER TO COMPETE WITH TAGLIONI. IT WAS GOOD BUSINESS TO PROMOTE RIVALRY. CLAQUES, OR PAID GROUPS WHO APPLAUDED FOR A PARTICULAR PERFORMER, CAME INTO VOGUE. ELLSLER’S MOST FAMOUS DANCE - LA CACHUCHA - A SPANISH CHARACTER NUMBER. IT BECAME AN OVERNIGHT CRAZE. FANNY ELLSLER TAGLIONI VS ELLSLER THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN TALGIONI AND ELLSLER: A. TAGLIONI REPRESENTED SPIRITUALITY 1. NOT MUCH ACTING ABILITY B. ELLSLER EXPRESSED PHYSICAL PASSION 1. CONSIDERABLE ACTING ABILITY THE RIVALRY BETWEEN THE TWO DID NOT CONFINE ITSELF TO WORDS. THERE WAS ACTUAL PHYSICAL VIOLENCE IN THE AUDIENCE! GISELLE THE BALLET, GISELLE, PREMIERED AT THE PARIS OPERA IN JUNE 1841 WITH CARLOTTA GRISI AND LUCIEN PETIPA. GISELLE IS A ROMANTIC CLASSIC. GISELLE WAS DEVELOPED THROUGH THE PROCESS OF COLLABORATION. GISELLE HAS REMAINED IN THE REPERTORY OF COMPANIES ALL OVER THE WORLD SINCE ITS PREMIERE WHILE LA SYLPHIDE FADED AWAY AFTER A FEW YEARS. ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR BALLETS EVER CREATED, GISELLE STICKS CLOSE TO ITS PREMIER IN MUSIC AND CHOREOGRAPHIC OUTLINE. IT DEMANDS THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF TECHNICAL SKILL FROM THE BALLERINA. GISELLE COLLABORATORS THEOPHILE GAUTIER 1811-1872 A POET AND JOURNALIST HAD A DOUBLE INSPIRATION - A BOOK BY HEINRICH HEINE ABOUT GERMAN LITERATURE AND FOLK LEGENDS AND A POEM BY VICTOR HUGO-AND PLANNED A BALLET. VERNOY DE SAINTS-GEORGES, A THEATRICAL WRITER, WROTE THE SCENARIO. ADOLPH ADAM - COMPOSER. THE SCORE CONTAINS MELODIC THEMES OR LEITMOTIFS WHICH ADVANCE THE STORY AND ARE SUITABLE TO THE CHARACTERS. -

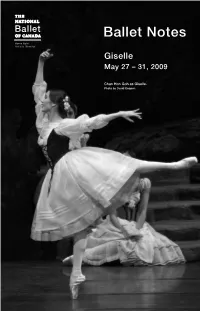

Ballet Notes Giselle

Ballet Notes Giselle May 27 – 31, 2009 Chan Hon Goh as Giselle. Photo by David Cooper. 2008/09 Orchestra Violins Clarinets • Fujiko Imajishi, • Max Christie, Principal Souvenir Book Concertmaster Emily Marlow, Lynn Kuo, Acting Principal Acting Concertmaster Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet On Sale Now in the Lobby Dominique Laplante, Bassoons Principal Second Violin Stephen Mosher, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., Founder James Aylesworth, Jerry Robinson Featuring beautiful new images Acting Assistant Elizabeth Gowen, George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Concertmaster by Canadian photographer Contra Bassoon Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Jennie Baccante Sian Richards Artistic Director Executive Director Sheldon Grabke Horns Xiao Grabke Gary Pattison, Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Nancy Kershaw Vincent Barbee Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Derek Conrod Principal Conductor • Csaba Koczó • Scott Wevers Yakov Lerner Trumpets Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Jayne Maddison Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Richard Sandals, Principal Ron Mah YOU dance / Ballet Master Mark Dharmaratnam Aya Miyagawa Raymond Tizzard Aleksandar Antonijevic, Guillaume Côté, Wendy Rogers Chan Hon Goh, Greta Hodgkinson, Filip Tomov Trombones Nehemiah Kish, Zdenek Konvalina, Joanna Zabrowarna David Archer, Principal Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Paul Zevenhuizen Robert Ferguson David Pell, Piotr Stanczyk, Xiao Nan Yu Violas Bass Trombone Angela Rudden, Principal Victoria Bertram, Kevin D. Bowles, Theresa Rudolph Koczó, Tuba -

Giselle Saison 2015-2016

Giselle Saison 2015-2016 Abonnez-vous ! sur www.theatreducapitole.fr Opéras Le Château de Barbe-Bleue Bartók (octobre) Le Prisonnier Dallapiccola (octobre) Rigoletto Verdi (novembre) Les Caprices de Marianne Sauguet (janvier) Les Fêtes vénitiennes Campra (février) Les Noces de Figaro Mozart (avril) L’Italienne à Alger Rossini (mai) Faust Gounod (juin) Ballets Giselle Belarbi (décembre) Coppélia Jude (mars) Paradis perdus Belarbi, Rodriguez (avril) Paquita Grand Pas – L’Oiseau de feu Vinogradov, Béjart (juin) RCS TOULOUSE B 387 987 811 - © Alexander Gouliaev - © B 387 987 811 TOULOUSE RCS Giselle Midis du Capitole, Chœur du Capitole, Cycle Présences vocales www.fnac.com Sur l’application mobile La Billetterie, et dans votre magasin Fnac et ses enseignes associées www.theatreducapitole.fr saison 2015/16 du capitole théâtre 05 61 63 13 13 Licences d’entrepreneur de spectacles 1-1052910, 2-1052938, 3-1052939 THÉÂTRE DU CAPITOLE Frédéric Chambert Directeur artistique Janine Macca Administratrice générale Kader Belarbi Directeur de la danse Julie Charlet (Giselle) et Davit Galstyan (Albrecht) en répétition dans Giselle, Ballet du Capitole, novembre 2015, photo David Herrero© Giselle Ballet en deux actes créé le 28 juin 1841 À l’Académie royale de Musique de Paris (Salle Le Peletier) Sur un livret de Théophile Gautier et de Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges D’après Heinrich Heine Nouvelle version d’après Jules Perrot et Jean Coralli (1841) Adolphe Adam musique Kader Belarbi chorégraphie et mise en scène Laure Muret assistante-chorégraphe Thierry Bosquet décors Olivier Bériot costumes Marc Deloche architecte-bijoutier Sylvain Chevallot lumières Monique Loudières, Étoile du Ballet de l’Opéra National de Paris maître de ballet invité Emmanuelle Broncin et Minh Pham maîtres de ballet Nouvelle production Ballet du Capitole Kader Belarbi direction Orchestre national du Capitole Philippe Béran direction Durée du spectacle : 2h25 Acte I : 60 min. -

H-France Review Vol. 11 (May 2011), No. 99 Annegret Fauser and Mark

H-France Review Volume 11 (2011) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 11 (May 2011), No. 99 Annegret Fauser and Mark Everist eds., Music, Theater, and Cultural Transfer: Paris, 1830-1914. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2009. x + 439 pp. Appendix, bibliography, discography and filmography, contributors, index. $55.00 U.S. (cl.) ISBN 978-0-226-23926-2 Review by Clair Rowden, Cardiff University. For those of us that work on French music during the nineteenth century, this book is a collection of essays that exemplifies what we do and yet it is far from banal. We ‘insiders’ tend to forget the honest and engaging nature of such work, studying and examining not only musical artefacts, but the aesthetic, cultural and institutional history which shaped those artworks and in turn forged the nature of our discipline. Annegret Fauser and Mark Everist, both at the height of their games, have given us a book which those in many other fields of musicological study may envy in its scope and integrity. Indeed, this book has already won the coveted Solie prize, awarded by the American Musicological Society, and I would not be surprised if it went on to win more. But as the editors-authors are quick to point out, this volume grew out of the international symposium, “The Institutions of Opera in Paris from the July Revolution to the Dreyfus Affair”, co-organised by Annegret Fauser and the late and much regretted Elizabeth C. Bartlett, and the book is both a tribute to the current discipline and to Beth Bartlett’s place within its development. -

Lincoln Center Festival 2012 Sponsor

Nonprofit Organization U.S. Postage PAID Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts July 5–August 5, 2012 70 Lincoln Center Plaza New York, NY 10023-6583 July 5–August 5, 2012 Tickets On Sale Now! LincolnCenterFestival.org 212.721.6500 Mikhail Baryshnikov and Paris Opera Ballet—Giselle Alan Cumming—Macbeth Cate Blanchett and Anna Sinyakina—In Paris Richard Roxburgh—Uncle Vanya cover artwork by Luciano De Liberato, photo by Gino Di Paolo, RED, 2003, acrylic on canvas, 31.5 x 31.5 in. Lincoln Center Festival 2012 Sponsor Major Support The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation JULY 11–22 Supporters Nancy A. Marks “For those who live for ballet virtuosity, LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust this is the company to see.” China International Culture Association The Skirball Foundation —New York Times The Harold & Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc. The Shubert Foundation Jennie and Richard DeScherer The Grand Marnier Foundation The Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies The Joelson Foundation The Harkness Foundation for Dance Georges Lurcy Charitable and Educational Trust Mitsui USA Foundation Great Performers Circle Chairman’s Council Producers Circle Friends of Lincoln Center Public support is provided by New York City Department of Cultural Affairs New York State Council on the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Endowment support is provided by Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Nancy Abeles Marks National Sponsor of Lincoln Center Official Sponsor of Lincoln Center Official Airline of Lincoln Center Official Broadcast Partner of Lincoln Center Official Wine of Lincoln Center Celebrate Summer at Lincoln Center Artist Catering Provider Orpheus and Eurydice 212.721.6500 1 Boléro Giselle Orpheus and Eurydice The legendary Paris Opera Ballet, the oldest national ballet company in the world and the one that literally invented the form, gives its first New York performances in more than 15 years. -

Le Fabuleux Destin Du Docteur Véron, Vesalius, X, I, 20-24, 2004

Le Fabuleux Destin du Docteur Véron, Vesalius, X, I, 20-24, 2004 Le Fabuleux Destin du Docteur Véron Claude A Planchon Résumé Extraordinaire odyssée que celui du Docteur Louis-Désiré Véron (1798-1867), Interne des Hôpitaux de Paris. Déçu par la médecine en un temps où l'on ne pouvait faire carrière à Paris sans « être bien-né », il prend une étonnante revanche sur la société, après avoir fait fortune par hasard dans la pharmacie. Il innove dans le journalisme en tant que précurseur de la publicité médicale. Il dirige, de main de maître, l'Opéra de Paris, rue Le Peletier, de 1831 à 1835, l'une des plus beiles périodes. Il y crée notamment, pour le lyrique, « Robert le Diable », de Meyerbeer et « La Sylphide », de Filippo Taglioni, l'une des pièces maîtresses du ballet romantique, interprétée par la propre fille du chorégraphe, MarieTaglioni.Véron en sera le protecteur. Malgré un physique ingrat, compensé par un esprit hors du commun,Véron séduira Rachel, la plus grande tragédienne du Théâtre-Français de I' époque. Summary The life of Doctor Louis-Desire Veron (1798-1867) was an incredible odyssey. Starting his professional life as an 'Interne des Hopitaux de Paris', he found himself unable to enter the medical establishment at a time when it was practically impossible to succeed in Parisian society without having being born into a wealthy family. He was eventually able to take his revenge on Paris when he had made a fortune from pharmacy. He became the head of the Le Pelletier Paris Opera (183 1-1835), in one of the most brilliant periods of opera history, with productions of Robert le Diable by Meyerbeer and La Sylphide, a ballet choreographed by FilippoTaglioni.This latter was first interpreted by Marie, the prima ballerina daughter of Taglioni. -

One Aim/One Vision: the Bolshoi Ballet in Still Photography

ave maria university presents One Aim/One Vision: The Bolshoi Ballet in Still Photography CANIZARO LiBRARY March 27-May 9, 2010 Marc Haegeman is a dance writer and photographer based in Belgium. He is a European correspondent for DanceView and Danceviewtimes (Washington DC) and writes the Russian Profile in Dance International (Vancouver). His reviews, features and interviews have also been published in The Dancing Times (London), Dance Now (London), Ballet2000 (Milan), Brolga (Australia), Ballet Magazine (Moscow), and Nezavisimaya Gazeta (Moscow). As Photographer he contributes to dance magazines worldwide, to souvenir program books of Moscow's Bolshoi Ballet and several web sites, including the personal web pages of Russian dancers, Svetlana Zakharova, Natalia Osipova, Daria Pavlenko, Nina Ananiashvili and Dmitry Gudanov, among others. His photos also illustrate the book by Isis Wirth, Despues de Giselle. Estética y Ballet en el Siglo XXI (Valencia, 2007). For more information about the photographer and his work please view: http://www.for-ballet-lovers-only.com. This exhibition has been made possible thanks to the cooperation of the Bolshoi Theatre. marc haegeman All photos © 2010 Marc Haegeman at Bolshoi Theatre. All Rights Reserved. LA SYLPHIDE: Staging produced by Johan Kobborg, principal dancer with London's Royal Ballet. Choreography by August Bournonville. Production and new choreography by Johan Kobborg. Sets and costumes by Peter Farmer. Lighting by Damir Ismagilov. 1 | Ekaterina Krysanova (the Sylphide) and Yan Godowsky (James). 2 | Ekaterina Krysanova (the Sylphide) and Yan Godowsky (James). 3 | Ekaterina Krysanova (the Sylphide). 4 | Vyacheslav Lopatin (James). 5 | Irina Zibrova (Madge, the witch) and artists of the Bolshoi Ballet. -

WILLIAM TELL Armando Noguera (William Tell) VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS WILLIAM TELL

GIOACHINO ROSSINI WILLIAM TELL Armando Noguera (William Tell) VICTORIAN OPERA PRESENTS WILLIAM TELL Composer Gioachino Rossini Librettists V.J Etienne de Jouy and H.L.F. Bis Conductor Richard Mills AM Director Rodula Gaitanou Set and Lighting Designer Simon Corder Costume Designer Esther Marie Hayes Assistant Director Meg Deyell CAST Guillaume Tell Armando Noguera Rodolphe Paul Biencourt Arnold Melcthal Carlos E. Bárcenas Ruodi Timothy Reynolds Walter Furst Jeremy Kleeman Leuthold Jerzy Kozlowski Melcthal Teddy Tahu Rhodes Mathilde Gisela Stille Jemmy Alexandra Flood Hedwige Liane Keegan Gesler Paolo Pecchioli* Orchestra Victoria 14, 17 and 19 JULY 2018 Palais Theatre, St Kilda Original premiere 3 August 1829, Paris Opera Running Time is 3 hours and 15 minutes, including interval Sung in French with English surtitles *Paolo Pecchioli appears with the support of the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, University of Melbourne. 3 PRODUCTION PRODUCTION TEAM Production Manager Eduard Inglés Stage Manager Marina Milankovic Deputy Stage Manager Meg Deyell Assistant Stage Manager Jessica Frost Assistant Stage Manager Luke Hales Wardrobe Supervisor Kate Glenn-Smith MUSIC STAFF Principal Repetiteur Phoebe Briggs Chorus Preparation Richard Mills, Phoebe Briggs Repetiteur Phillipa Safey CHORUS Soprano Jordan Auld*, Kirilie Blythman, Jesika Clark*, Rosie Cocklin*, Alexandra Ioan, Millie Leaver*, Rebecca Rashleigh, Diana Simpson, Emily Uhlrich, Nicole Wallace Mezzo Soprano Kerrie Bolton, Shakira Dugan, Jessie Eastwood*, Kristina Fekonja*, Hannah Kostros*, -

Donor Impact Report – Winter 2019

BALLET ARIZONA DONOR IMPACT Foundation Highlight: Donor Spotlight: Letter From the Q&A: Barbara Donald Ottosen Janet Fabio Executive Director: Artistic Director REPORT Samantha Turner Ib Andersen TURNING POINTE How your support creates exciting new opportunities for growth and development. Sketching by Fabio Toblini. WINTER Our work depends on you and we are forever grateful for you. Welcome to 2019! We are excited to kick off the New Year BEHIND THE SCENES with the world-premiere of my new work The Firebird alongside with Ib Andersen one of the oldest classical ballet’s La Sylphide this February at Symphony Hall, it will be a spectacular evening of ballet. Let’s talk about The Firebird… I want to extend a special thank you to Barbara & Donald Ottosen, longtime patrons and supporters of Ballet Arizona, The Firebird is a ballet that is taken from several different Russian whose generosity has made The Firebird possible. I am truly fairy tales that were stitched together to create the story as we grateful for their support of my artistic vision for this ballet know it today. It was created for Ballets Russes in 1910 and was and for this company. Stravinsky’s first ballet. It’s a traditional story of good versus evil painted with big brush strokes so it is very easy to understand In this issue of Turning Pointe, Executive Director Samantha upon first viewing. It is a ballet meant for all ages, both adults and Turner discusses the incredible impact you made this past fall children will enjoy it. I’m following the original piece – more or less on five schools across the Valley through our new danceAZ – the only difference here is that I have placed my version in the school residency program.