How Continuing Education and Schools of Management Collide and Cooperate Jay A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE September 2013 JOHN L. GRIFFITH, PhD Associate Dean for Research Bouvé College of Health Sciences Northeastern University Office of Research, Bouvé College of Health Sciences 110 Behrakis Health Science Center Northeastern University 360 Huntington Avenue Boston, MA. 02115 Telephone: (617) 373-7516 EDUCATION Boston University, Boston, MA Ph.D. Mathematics 1994 Tufts University, Medford, MA M.S. Mathematics 1982 Claremont Men's College, Claremont, CA. B.A. 1976 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Bouvé College of Health Sciences, Northeastern University 2012 - Present Professor, Departments of Health Sciences and Counseling and Applied Educational Psychology Tufts Sackler Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences 2002 - 2012 Associate Professor of Medicine Tufts University School of Medicine 2102 - Present Adjunct Associate Professor of Medicine 1999 - 2012 Associate Professor of Medicine 1996 - 2012 Assistant Professor of Family Medicine and Community Health 1993 - 1999 Assistant Professor of Medicine Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine 1995 Quantitative Course Director, Animals and Public Policy Boston University 1982-1990 Lecturer, Department of Mathematics Tufts University 1980-1982 Lecturer, Department of Mathematics Curriculum Vitae - John L Griffith Page 2 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Journal Reviewer Clinical Infectious Disease, -

Babson College Impact Report 2019-2020 (Pdf)

IMPACT REPORT 2019–2020 WE ARE BABSON. WE BELIEVE … Entrepreneurship is core to humanity. We each carry within us vast potential to create new solutions, act on our values, and impact the world in positive and powerful ways. Babson can unleash and amplify this potential to have impact. With a developed entrepreneurial mindset, training, and inspiration, people everywhere can create lasting value for ourselves, our communities, and the world. How we learn, teach, and operate must evolve. We each must continually reinvent ourselves by acquiring new skills and knowledge. Colleges and universities also must reinvent themselves, engaging learners more deeply, co-creating relevant, experiential learning and real problem-solving opportunities. Entrepreneurship is the most powerful driver of positive change. Entrepreneurship is the most powerful tool there is to confront and overcome today’s challenges and find opportunity in change. We are stronger together. We can achieve more when we move powerfully together, respecting and trusting each other, developing and strengthening networks, and connecting with diverse, multiple, even unlikely partners in order to accomplish shared goals. We must break barriers to access and opportunity. We can create value for everyone, everywhere. There can be no edge. Everyone should have access to opportunities, and to the tools for learning and untethered self-determination. We can have impact everywhere. We can educate and act across geography, across politics, across demographics, and across the lifespan. There is no choice between societal and economic value. We must have both. Each creates and strengthens the other. Finding, developing, and scaling opportunities that do both, simultaneously, is the ultimate challenge of our time. -

I. Benchmarking

I. BENCHMARKING 1 Education & General Budget Mason's National Peer Group of Institutions Expenditures Per Student ‐ FY 2009 Actual TtlTotal TtlTotal EditExpenditures Institution: Expenditures Enrollment Per Student University of Connecticut$ 827.2 22,663 $ 36,501 Boston University 1,038.1 30,779 33,727 George Washington University 661.9 20,450 32,367 Syracuse University 486.4 19,179 25,362 University of Louisville 429.4 17,421 24,649 University of Nevada ‐ Reno 323.1 13,511 23,917 Indiana Univ‐Purdue Univ‐Indianapolis 615.4 26,634 23,104 SUNY at Buffalo 601.0 27,115 22,165 Northeastern University 513.6 23,539 21,820 Wayne State University 502.3 23,219 21,635 University of Maryland‐College Park 698.0 32,584 21,421 University of Kansas Main Campus 525.4 25,764 20,393 Indiana University ‐ Bloomington 747.3 39,002 19,161 SUNY at Albany 311.5 16, 281 19, 134 University of New Mexico ‐ Main 412.1 21,739 18,958 University of Cincinnati ‐ Main 474.3 26,274 18,051 University of Oklahoma Norman 388.9 22,114 17,585 University of Nebraska at Lincoln 331.3 20,984 15,788 University of Houston 459.0 29,765 15,420 Arizona State University ‐ Tempe 892.3 58,818 15,172 University of Arkansas ‐ Main 256.7 17,130 14,983 University of Missouri‐Columbia 398.6 27,139 14,687 University of Memphis 240.7 16,767 14,357 University of Nevada ‐ Las Vegas 338.8 24,040 14,093 Georgia State University 294.6 27,816 10,589 Peer Average$ 510.7 25,229 $ 20,602 George Mason University$ 344.7 23,297 $ 14,798 Mason % of Average 67% 92% 72% In FY 2009, Mason operates spending 72% of its peer average spending level. -

Babson College Will Expand to Miami with Graduate Programs | Miami

Kerry Healey is the president of Babson College. BUSINESS JULY 21, 2017 9:00 AM Babson College plans to launch Miami campus for graduate programs BY NANCY DAHLBERG [email protected] Babson College plans to announce Monday that it is expanding to Miami, where it will begin offering some of its top-ranked graduate programs in the fall of 2018. Babson’s newest hub, which will be located at the Cambridge Innovation Center at 1951 NW 7th Ave., will build on its base of 1,300 area alumni, the institution’s fourth largest alumni group, and a growing relationship in Miami’s entrepreneurship community. Miami will be Babson’s third location outside its main campus in Wellesley, Mass. It also has campuses in Boston and San Francisco. The Miami expansion is part of Babson President Kerry Healey’s global growth strategy. ADVERTISING “We think Miami is a wonderful place geographically for us to be. It helps us cover the country in an important way but also it allows us to be where the entrepreneurs are,” said Healey, noting that Miami ranked No. 1 for startup activity in the 2017 Kauffman Index report. The graduate programs have been approved by the State of Florida and will include one of Babson’s premier degrees, its Blended Learning MBA, which combines online and face-to-face instruction, Healey said. That graduate program is ranked No. 5 in the nation and No. 1 for average alumni earnings by the Financial Times. In the hot field of big data, a Master of Science in Business Analytics will be offered, she said. -

2019 Annual Security and Fire Report

2019 Babson College Annual Security & Fire Report Wellesley, MA Boston, MA San Francisco, CA Miami, FL Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1-4 About the Jeanne Clery Act .......................................................................................................... 1 About the Annual Security & Fire Report .................................................................................1-2 Campus Security Authorities ...................................................................................................... 2 About Babson College ................................................................................................................. 2 The Babson College Public Safety Department ........................................................................ 2-4 Reporting Crimes or Other Emergencies ............................................................. 5-7 Policies/Procedures Regarding Reporting Criminal Actions or Other Emergencies .............. 5-6 Policies that Encourage Accurate & Prompt Reporting of All Crimes to the Campus Police & the Appropriate Police Agencies .............................................................................................. 6-7 Campus Sex Offender Reporting .................................................................................................. 7 Security & Access to Campus Facilities................................................................... 8 Fire -

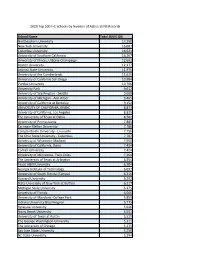

School Name Total SEVIS IDS Northeastern University

2020 Top 500 F-1 Schools by Number of Active SEVIS Records School Name Total SEVIS IDS Northeastern University 17,290 New York University 16,667 Columbia University 16,631 University of Southern California 16,207 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 12,692 Boston University 12,177 Arizona State University 11,975 University of the Cumberlands 11,625 University of California San Diego 10,984 Purdue University 10,706 University Park 9,612 University of Washington - Seattle 9,608 University of Michigan - Ann Arbor 9,465 University of California at Berkeley 9,152 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 8,873 University of California, Los Angeles 8,825 The University of Texas at Dallas 8,582 University of Pennsylvania 7,885 Carnegie Mellon University 7,786 Campbellsville University - Louisville 7,756 The Ohio State University - Columbus 7,707 University of Wisconsin-Madison 7,550 University of California, Davis 7,434 Cornell University 7,424 University of Minnesota, Twin Cities 7,264 The University of Texas at Arlington 6,954 Texas A&M University 6,704 Georgia Institute of Technology 6,697 University of South Florida (Tampa) 6,316 Harvard University 6,292 State University of New York at Buffalo 6,217 Michigan State University 6,175 University of Florida 6,065 University of Maryland -College Park 5,859 Indiana University Bloomington 5,775 Syracuse University 5,646 Stony Brook University 5,591 University of Texas at Austin 5,529 The George Washington University 5,311 The University of Chicago 5,275 San Jose State University 5,250 NC State University 5,194 Harrisburg University of Science & Tech 5,127 University of Illinois at Chicago 5,120 Stanford University 4,983 Duke University & Health Sys. -

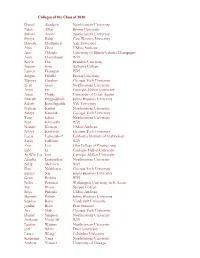

Colleges of the Class of 2020 Daniel Abadjiev Northeastern University

Colleges of the Class of 2020 Daniel Abadjiev Northeastern University Eden Allen Brown University Suhani Amin Northeastern University Shreya Balaji Case Western University Danush Chelladurai Yale University Alan Chen UMass Amherst Arav Chheda University of Illinois-Urbana Champagne Arun Chintalapati WPI Kevin Dai Brandeis University Maxim Enis Williams College Lauren Flanagan WPI Megan Frisella Brown University Marissa Gardner Georgia Tech University Evan Gaus Northeastern University Anna He Carnegie-Mellon University Arjun Hegde University of Texas-Austin Bharath Heggadahalli Johns Hopkins University Saketh Jonnalagadda Yale University Nathan Kadria Northeastern University Aditya Kaushik Georgia Tech University Tom Khuu Northeastern University Ivan Klevanski WPI Nonnie Komon UMass Amherst Nikhil Krishnan Georgia Tech University Lucas Lanzendorf California Institute of Technology Sarah LaRusso WPI Zoie Leo Olin College of Engineering Eric Li Carnegie-Mellon University Ai-Wen Joy Lim Carnegie-Mellon University Anusha Loganathan Northeastern University Nilay McLaren WPI Dan Nedelescu Georgia Tech University Esther Ng Johns Hopkins University Grant Perkins WPI Neha Perumal Washington University in St. Louis Mai Pham Scripps College Sriya Pidatala UMass Amherst Hannah Puhov Johns Hopkins University Supriyo Rana Vanderbilt University Jordan Roth Pratt Institute Avi Shah Georgia Tech University Daniel Simpson Northeastern University Anthony Vuolo III WPI Lauren Wagner Northeastern University Joel White Duke University Lance Wong Columbia University Katherine Yang Northeastern University Andrew Youssef University of Chicago . -

P E R a P E R a Annual Report Annual Report

WWellesleyellesley CCollegeollege 2007-08 PPERAE R A AAnnualnnual RReporteport “PERA is the catalyst for all students to learn, play, compete and achieve an active balanced lifestyle.” The Wellesley College department of Physical Education, Recreation and Athletics is dedicated to promoting an improved quality of life for all Wellesley College students through increased understanding, skill, competititon and participation in physical activity. The Department meets the needs of a variety of students through its three programs and also partnerships with a wide variety of campus departments. • Physical Education: instructional classes • Recreation: leisure time activities • Athletics: intercollegiate competitive teams 22007-08007-08 PPERAERA DDepartmentepartment GGoalsoals Continuing to build on the success of 2006-07, the department further enhanced communication, collaboration and integration among the campus community (students, faculty, staff) in support of physical fi tness, recreational activities and intercollegiate competition, valued components of life-long learning. Additionally, the PERA department strengthened its commitment to diversity among participants in all areas of interest. Signifi cant progress: o Engaged in PERA Department Strategic Planning Process. o Integrated all faculty/staff in department-wide committee structure. o Updated PERA Department Faculty/Staff Handbook; posted on Administrative webpage. o Received NCAA Speakers Grant and NCAA Initiatives Grant to support PERA Faculty/Staff and Student-Athlete Diversity Workshop in February. o FOWCA fi nancial support of athletics program; $30,000 team competitive training trips; $15,000 annual “wish list” gifts and $25,000 for weight and cardio equipment. 1 Collaborations o Partnered with Alumnae Association to promote athletics through email updates to alumnae chapters in areas where teams visited for Spring Break and sponsored Alumnae Athlete Reception during June Reunion and supported fi tness activity for Alumnae Board of Directors. -

50Th NSEE Annual Conference Orlando, Florida September 27

th 50 NSEE Annual Conference Orlando, Florida September 27 - 29 Linda Abrams Bob Jones University Southern Audrey Allison Kennesaw State University Southern Tammara Anderson University of Southern California Western Kerry Arens Webster Groves High School Midwest Alexandria Beedle Texas A&M University-San Antonio Western Christine Blais Southern New Hampshire University Northeast Edwin Blanton Texas A&M University - San Antonio Western Jodi Blubaugh Mount Aloysius College Northeast Connie Book Elon University Southern Somer Burke University of South Florida College of Public Health Southern Rebecca Burwell Chicago Semester/Trinity Christian College Midwest Tara Campbell Stony Brook University Northeast Ete Chan-Lo Stony Brook University Northeast Rhonda Cochran Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences Western James Colbert Lander University Southern Caitlin Curtis University of Wisconsin-Parkside Midwest Meredith Daw University of Chicago Midwest Don DeGraaf Chicago Semester - Chicago, IL Midwest Donald DeMaria University of Georgia Southern Kimberly Dixon Stony Brook University Northeast Jennifer Dobbs-Oates Purdue University Midwest Tannette Elie University of Wisconsin-Parkside Midwest Carly Eppler The College of Wooster Midwest Kimberly Filer Virginia Tech Mid-Atlantic Hilary Flanagan Seattle University Western Millinda Fowles University of Kansas Midwest Mysti Frazier Texas A&M University-San Antonio Western Beth Garcia West Texas A&M University Western Megan Gassman Southern New Hampshire University Northeast This is -

MS in Advanced and Intelligent Manufacturing (AIM)

Proposal for New Program MS in Advanced and Intelligent Manufacturing (AIM) Graduate School of Engineering AIM MS Proposal Led & Prepared by Sagar Kamarthi Intended AIM MS Co-directors to be Hongli ‘Julie’ Zhu and Xiaoning ‘Sarah’ Jin Nov 20, 2020 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the last five years, the United States has seen a resurgence in advanced manufacturing fueled in part by the creation of 14 National Network of Manufacturing Innovation Institutes. The US government and industry have invested several billion dollars to revitalize advanced manufacturing in the US. As a result, all stakeholders including industry, academia, research labs, and government agencies have been forming strong partnerships to rapidly transfer science and technology into manufacturing high-tech products and processes. To meet the current and projected demand for engineers, researchers, and scientists trained in advanced and smart manufacturing and leverage Northeastern’s recognized research and development in nano and microscale manufacturing, smart manufacturing, and data analytics, the College of Engineering (COE) proposes to start a new graduate program, MS in Advanced and Intelligent Manufacturing (AIM). This program will enable students to acquire the necessary engineering, analytical and research skills to design, supervise, and manage advanced and manufacturing facilities and projects in industry, government or academia. Figure 1 depicts an infographic of advanced and smart manufacturing1. The program will address conventional manufacturing as well as advanced manufacturing. Conventional manufacturing covers topics such metal removal, forming, casting, and particulate processes. In contrast advanced manufacturing covers topics such as nanomanufacturing, fabrication and printing of micro and nano devices, additive 3D printing of parts, electronics, sensors, medical, materials and energy applications. -

Preseason – Oct. 2, 2000 Week 2 – Oct. 9, 2000 1. University of North Dakota 1

Preseason – Oct. 2, 2000 Week 2 – Oct. 9, 2000 1. University of North Dakota 1. University of North Dakota 2. University of Michigan 2. University of Wisconsin 3. University of Wisconsin 3. University of New Hampshire 4. Michigan State University T4. Boston College 5. Boston College T4. University of Michigan 6. University of New Hampshire 6. Boston University 7. Boston University 7. Michigan State University 8. St. Lawrence University 8. St. Lawrence University 9. University of Maine 9. University of Minnesota 10. St. Cloud State University 10. University of Maine 11. Cornell University 11. Colgate University 12. University of Minnesota 12. St. Cloud State University 13. Lake Superior State University 13. Cornell University 14. University of Nebraska-Omaha 14. University of Nebraska-Omaha 15. Colorado College 15. Colorado College Week 3 – Oct. 16, 2000 Week 4 – Oct. 23, 2000 1. University of North Dakota 1. University of Wisconsin 2. University of Wisconsin 2. Boston College 3. Boston College 3. University of New Hampshire 4. University of New Hampshire 4. University of Michigan 5. University of Michigan 5. University of North Dakota 6. University of Minnesota 6. University of Minnesota 7. Michigan State University 7. University of Maine 8. University of Maine 8. St. Cloud State University 9. St. Cloud State University 9. Michigan State University 10. Boston University 10. Colorado College 11. Colorado College 11. Boston University 12. Colgate University 12. University of Nebraska-Omaha T13. St. Lawrence University 13. Cornell University T13. Cornell University 14. Colgate University 15. University of Nebraska-Omaha T15. Providence College T15. St. Lawrence University Week 5 – Oct. -

Preseason – Oct. 1, 2007 Week 2 – Oct. 8, 2007 1. University of North Dakota 1. University of North Dakota 2. Michigan State University 2

Preseason – Oct. 1, 2007 Week 2 – Oct. 8, 2007 1. University of North Dakota 1. University of North Dakota 2. Michigan State University 2. Boston College 3. Boston College 3. Michigan State University 4. University of Minnesota 4. Miami (Ohio) University 5. Miami (Ohio) University 5. University of New Hampshire 6. University of New Hampshire 6. University of Minnesota 7. Clarkson University 7. University of Notre Dame 8. University of Notre Dame 8. Boston University 9. Boston University 9. University of Michigan 10. University of Michigan 10. University of Denver 11. Colorado College 11. Colorado College 12. University of Denver 12. St. Lawrence University 13. University of Maine 13. Clarkson University 14. University of Wisconsin 14. University of Wisconsin 15. Quinnipiac University 15. University of Maine Week 3 – Oct. 15, 2007 Week 4 – Oct. 22, 2007 1. University of North Dakota 1. University of North Dakota 2. Miami (Ohio) University 2. Miami (Ohio) University 3. University of Minnesota 3. University of Michigan 4. Boston College 4. Colorado College 5. University of Denver 5. Boston College 6. University of Michigan 6. University of New Hampshire 7. Clarkson University 7. University of Denver 8. University of New Hampshire 8. Clarkson University 9. Michigan State University 9. Michigan State University 10. Colorado College 10. University of Minnesota 11. University of Notre Dame 11. University of Wisconsin 12. Ohio State University 12. University of Notre Dame T13. St. Lawrence University 13. University of Maine T13. University of Wisconsin 14. Ohio State University T15. University of Massachusetts 15. Michigan Tech University T15. Quinnipiac University Week 5 – Oct.