Lye Poisoning in “A Worn Path”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

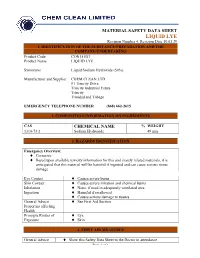

Liquid Lye MSDS

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET LIQUID LYE Revision Number 4, Revision Date 10.01.29 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE/PREPARATION AND THE COMPANY/UNDERTAKING Product Code CON151BT Product Name LIQUID LYE Synonyms Liquid Sodium Hydroxide (50%) Manufacturer and Supplier CHEM CLEAN LTD #1 Trincity Drive Trincity Industrial Estate Trincity Trinidad and Tobago EMERGENCY TELEPHONE NUMBER (868) 662-2615 2. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS CAS CHEMICAL NAME % WEIGHT 1310-73-2 Sodium Hydroxide 49 min 3. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview: ♦ Corrosive ♦ Based upon available toxicity information for this and closely related materials, it is anticipated that this material will be harmful if ingested and can cause serious tissue damage Eye Contact ♦ Causes severe burns Skin Contact ♦ Causes severe irritation and chemical burns Inhalation ♦ None, if used in adequately ventilated area Ingestion ♦ Harmful if swallowed ♦ Causes serious damage to tissues General Advice ♦ See First Aid Section Properties affecting Health Principle Routes of ♦ Eye Exposure ♦ Skin 4. FIRST AID MEASURES General Advice ♦ Show this Safety Data Sheet to the Doctor in attendance Page 1 of 6 LIQUID LYE Skin Contact ♦ Immediately apply vinegar if readily available ♦ Immediately flush skin with plenty of cool running water for at least 15 minutes ♦ Immediately remove contaminated clothing ♦ Immediate Medical Attention is required if irritation persists or burns develop Eye Contact ♦ In case of eye contact, remove contact lens and rinse immediately with plenty of water, -

Small Episodes, Big Detectives

Small Episodes, Big Detectives A genealogy of Detective Fiction and its Relation to Serialization MA Thesis Written by Bernardo Palau Cabrera Student Number: 11394145 Supervised by Toni Pape Ph.D. Second reader Mark Stewart Ph.D. MA in Media Studies - Television and Cross-Media Culture Graduate School of Humanities June 29th, 2018 Acknowledgments As I have learned from writing this research, every good detective has a sidekick that helps him throughout the investigation and plays an important role in the case solving process, sometimes without even knowing how important his or her contributions are for the final result. In my case, I had two sidekicks without whom this project would have never seen the light of day. Therefore, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Toni Pape, whose feedback and kind advice was of great help. Thank you for helping me focus on the important and being challenging and supportive at the same time. I would also like to thank my wife, Daniela Salas, who has contributed with her useful insight, continuous encouragement and infinite patience, not only in the last months but in the whole master’s program. “Small Episodes, Big Detectives” 2 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 1. Literature Seriality in the Victorian era .................................................................... 8 1.1. The Pickwick revolution ................................................................................... 8 -

SODIUM HYDROXIDE @Lye, Limewater, Lyewater@

Oregon Department of Human Services Office of Environmental Public Health (503) 731-4030 Emergency 800 NE Oregon Street #604 (971) 673-0405 Portland, OR 97232-2162 (971) 673-0457 FAX (971) 673-0372 TTY-Nonvoice TECHNICAL BULLETIN HEALTH EFFECTS INFORMATION Prepared by: ENVIRONMENTAL TOXICOLOGY SECTION OCTOBER, 1998 SODIUM HYDROXIDE @Lye, limewater, lyewater@ For More Information Contact: Environmental Toxicology Section (971) 673-0440 Drinking Water Section (971) 673-0405 Technical Bulletin - Health Effects Information Sodium Hydroxide Page 2 SYNONYMS: Caustic soda, sodium hydrate, soda lye, lye, natrium hydroxide CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL PROPERTIES: - Molecular Formula: NaOH - White solid, crystals or powder, will draw moisture from the air and become damp on exposure - Odorless, flat, sweetish flavor - Pure solid material or concentrated solutions are extremely caustic, immediately injurious to skin, eyes and respiratory system WHERE DOES IT COME FROM? Sodium hydroxide is extracted from seawater or other brines by industrial processes. WHAT ARE THE PRINCIPLE USES OF SODIUM HYDROXIDE? Sodium hydroxide is an ingredient of many household products used for cleaning and disinfecting, in many cosmetic products such as mouth washes, tooth paste and lotions, and in food and beverage production for adjustment of pH and as a stabilizer. In its concentrated form (lye) it is used as a household drain cleaner because of its ability to dissolve organic solids. It is also used in many industries including glassmaking, paper manufacturing and mining. It is used widely in medications, for regulation of acidity. Sodium hydroxide may be used to counteract acidity in swimming pool water, or in drinking water. IS SODIUM HYDROXIDE NATURALLY PRESENT IN DRINKING WATER? Yes, because sodium and hydroxide ions are common natural mineral substances, they are present in many natural soils, in groundwater, in plants and in animal tissues. -

DRAFT Staff Report

COMMISSION FOR HISTORICAL & ARCHITECTURAL PRESERVATION Brandon M. Scott Tom Liebel, Chairman Chris Ryer Mayor Director STAFF REPORT February 9, 2021 REQUEST: Construct rear/rooftop addition with front deck/balcony ADDRESS: 223 E. Churchill Street (Federal Hill Historic District) APPLICANT: Jim Shetler, AIA, Trace Architects OWNER: Andrew Germek STAFF: Walter W. Gallas, AICP RECOMMENDATION: Approval with final details to be reviewed and approved by CHAP staff SITE/HISTORIC DISTRICT General Area: The property is located in the Federal Hill Historic District on the south side of E. Churchill Street in a block bounded by William Street on the west, Warren Avenue on the south, and Battery Street on the east. (Images 1-2). Comprising about 24 city blocks with street names retained from its original colonial settlement, Federal Hill is located just south of the Inner Harbor. At its northeast corner, Federal Hill Park rises steeply from Key Highway overlooking the downtown skyline. The neighborhood retains intact streets of largely residential properties reflecting the eras in which they were built and the economic status of their early residents. Site Conditions: The existing property is a narrow two-bay two-story masonry house with a shallow side-gabled roof. The three windows at the façade are 6/6. The first floor window and the front door with transom have jack arches. Along the east side of the house is a narrow walkway accessing the rear, and which has an easement enabling access to the rear yards of houses on Warren Avenue (Images 3-5). The house appears on the 1890 Sanborn map, looking like the smallest house on the block, with two stories and a one-story rear addition (Image 6). -

Notes for an Unwritten Biography of William Trevor

Colby Quarterly Volume 38 Issue 3 September Article 4 September 2002 "Bleak Splendour": Notes for an Unwritten Biography of William Trevor Denis Sampson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 38, no.3, September 2002, p. 280-294 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Sampson: "Bleak Splendour": Notes for an Unwritten Biography of William Tr "Bleak Splendour": Notes for an Unwritten Biography of William Trevor By DENIS SAMPSON IILITERARY BIOGRAPHERS," William Trevor has ren1arked, "often make the mistake of choosing the wrong subjects. A novelist-or any artist admired for what he produces, may not necessarily have lived anything but the most mundane of lives" (Excursions 176). His remark is a warning to any prospective biographer of Trevor himself, his way of implying that his own life has no worthwhile story. Yet the warning has its own paradoxical interest, for surely it is Trevor's particular gift to make literature out of the mundane. His refusal to dramatize the artistic self, to adopt heroic or romantic postures, somehow allows him to absorb and honor his mundane material, to find a tone that mirrors the inner lives of his unheroic characters. The consistency of that tone is his major accomplishment, according to John Banville: "his inimitable, calmly ambiguous voice can mingle in a single sentence pathos and humor, outrage and irony, mockery and love.... He is almost unique among n10dem novelists in that his own voice is never allowed to intrude into his fiction" (Paulson 166-67). -

Chemical Compatibility Guide

APPENDIX E CHEMICAL COMPATIBILITY GUIDE DISCLAIMER: This chart is intended to provide general guidance on chemical compatibility and should not be used for product selection. The chart is based on industry data and may not be applicable to your specific applications. Temperature, fluid concentration and other process conditions may affect the material compatibility. If there is uncertainty about the suitability of the material with the process chemical, Macnaught recommends physical testing of the sample material with the chemical. If further assistance is required, Macnaught's Technical Support Team can provide advice to assist with selection. S Recommended S E E L L RI Data not available RI E E E — E E E S S ST ST 61 Not recommended 61 0 0 S S 6 6 S S E E M M N N L L O O N N I I T T N N A A Y Y O O T T R R N N M M B B S S E E O O S S R R M M UMINIU UMINIU F F 6 6 T T A A K K 1 1 AL PP AL PP C VI PT F C VI PT F 3 3 Acetaldehyde — Aluminum Chloride 20% — — Acetamide — Aluminum Fluoride — — — Acetate Solvent — — — Aluminum Hydroxide — — Acetic Acid — — — Aluminum Nitrate — — — Aluminum Potassium Acetic Acid 20% Sulfate 10% — — — — Acetic Acid 80% — — — Aluminum Sulfate — Acetic Acid, Glacial — — Alums — — — — — Acetic Anhydride — Amines — — — — Acetone — Ammonia 10% — — Acetyl Chloride (dry) — — Ammonia Nitrate — — — — — Acetylene Ammonia, anhydrous — — — Acrylonitrile — — — Ammonia, liquid — — — Adipic Acid — Ammonium Acetate — — — Alcohols: Amyl — — — — Ammonium Bifluoride — — — — Alcohols: Benzyl — — — — Ammonium Carbonate — — Alcohols: -

Social Justice Themes in Literature

Social Justice Themes in Literature Access to natural resources Agism Child labour Civil war Domestic violence Education Family dysfunction Gender inequality Government oppression Health issues Human trafficking Immigrant issues Indigenous issues LGBTQ+ issues Mental illness Organized crime Poverty Racism Religious issues Right to freedon of speech Right to justice Social services and addiction POVERTY Title Author Summaries The Glass Castle Jeannette Walls When sober, Jeannette’s brilliant and charismatic father captured his children’s imagination. But when he drank, he was dishonest and destructive. Her mother was a free spirit who abhorred the idea of domesticity and didn’t want the responsibility of raising a family. Angela’s Ashes Frank McCourt So begins the luminous memoir of Frank McCourt, born in Depression-era Brooklyn to recent Irish immigrants and raised in the slums of Limerick, Ireland. Frank’s mother, Angela, has no money to feed the children since Frank’s father, Malachy, rarely works, and when he does he drinks his wages. Yet Malachy — exasperating, irresponsible, and beguiling — does nurture in Frank an appetite for the one thing he can provide: a story. Frank lives for his father’s tales of Cuchulain, who saved Ireland, and of the Angel on the Seventh Step, who brings his mother babies. Buried Onions Gary Soto For Eddie there isn’t much to do in his rundown neighborhood but eat, sleep, watch out for drive-bys, and just try to get through each day. His father, two uncles, and his best friend are all dead, and it’s a struggle not to end up the same way. -

BRYCE FORTNER Director of Photography Brycefortner.Com

BRYCE FORTNER Director of Photography brycefortner.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS A MILLION LITTLE THINGS James Griffiths KAPITAL ENTERTAINMENT / ABC Pilot & Season 4 Various Directors Chris Smirnoff, DJ Nash Aaron Kaplan STARGIRL 2 Julia Hart GOTHAM GROUP / DISNEY+ Feature Film Nathan Kelly, Jordan Horowitz Ellen Goldsmith-Vein HELLO, GOODBYE AND EVERYTHING Michael Lewen ACE ENTERTAINMENT IN BETWEEN Feature Film Chris Foss, Max Siemers I’M YOUR WOMAN Julia Hart AMAZON Feature Film Jordan Horowitz, Rachel Brosnahan STARGIRL Julia Hart GOTHAM GROUP / PRINCIPAL DISNEY Feature Film Jim Powers, Jordan Horowitz DOLLFACE Matt Spicer ABC SIGNATURE / HULU Pilot Melanie Elin, Stephanie Laing BROKEN DIAMONDS Peter Sattler BLACK LABEL Feature Film Ellen Schwartz, Mary Sparacio THE MAYOR James Griffiths ABC Pilot Scott Printz, Jean Hester PROFESSOR MARSTON & THE Angela Robinson SONY WONDER WOMEN Terry Leonard, Amy Redford Feature Film Andrea Sperling, Jill Soloway THE TICK Wally Pfister SONY / AMAZON Pilot Kerry Orent, Barry Josephson INGRID GOES WEST Feature Film Matt Spicer STAR THROWER ENTERTAINMENT Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival Jared Goldman HOUSE OF CARDS Wally Pfister NETFLIX Season 4 Promos CHARITY CASE James Griffiths ABC / FOX Pilot Scott Printz, Thea Mann PUNCHING HENRY Feature Film Gregori Viens Ian Coyne, David Permut Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival FLAKED Wally Pfister NETFLIX Series Josh Gordon Tiffany Moore, Mitch Hurwitz Will Arnett TOO LEGIT Short Frankie Shaw Liz Destro Official Selection, -

Safety Data Sheet Caustic Soda Liquid (All Grades)

Caustic Soda Liquid (All Grades) M32415_ROW_BE SAFETY DATA SHEET CAUSTIC SODA LIQUID (ALL GRADES) MSDS No.: M32415 Rev. Date: 31-May-2009 Rev. Num.: 05 _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. CHEMICAL PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Company Identification: Occidental Chemical Corporation 5005 LBJ Freeway P.O. Box 809050 Dallas, Texas 75380-9050 24 Hour Emergency Telephone 1-800-733-3665 or 1-972-404-3228 (U.S.); 32.3.575.55.55 (Europe); 1800-033-111 Number: (Australia) To Request an MSDS: [email protected] or 1-972-404-3245 Customer Service: 1-800-752-5151 or 1-972-404-3700 Trade Name: Caustic Soda Diaphragm Grade 10%, 15%, 18%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 35%, 40%, 50%, Caustic Soda Rayon Grade 18%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 50%, 50% Caustic Soda Rayon Grade OS, Caustic Soda Membrane 6%, 18%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 48%, 50%, 50% Caustic Soda Membrane OS, 50% Caustic Soda Diaphragm OS, Caustic Soda Low Salt 50%, 25% Caustic Soda Purified, 50% Caustic Soda Purified, 50% Caustic Soda Purified OS, Caustic Soda Liquid 70/30, Membrane Blended, 50% Caustic Soda Membrane (Northeast), 50% Caustic Soda Diaphragm (West Coast), 50% Blended Rayon Grade Blended, Membrane Cell Liquor Synonyms: Sodium hydroxide solution, Liquid Caustic, Lye Solution, Caustic, Lye, Soda Lye Product Use: Metal finishing, Cleaner, Process chemical, Petroleum industry _________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

The Public Buildings of Pensacola, 1818

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 16 Number 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 16, Article 7 Issue 1 1937 The Public Buildings of Pensacola, 1818 Andrew Jackson Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Jackson, Andrew (1937) "The Public Buildings of Pensacola, 1818," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 16 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol16/iss1/7 Jackson: The Public Buildings of Pensacola, 1818 45 THE PUBLIC BUILDINGS OF PENSACOLA, 1818 * Description and conditions of the public buildings in the town of Pensacola, delivered to Lieut. A. L. Sands of the U. S. Corps of Artillery, agreeably to the articles of capitulation, en- tered into at the Barrancas on the 28th day of May, 1818, between his excellency the Gov- ernor of the Province of West Florida, and Major Gen. Andrew Jackson of the U. S. Army - Viz: One Brick Guard house, with prisons 931/2 feet long, by 19 feet wide; with a wooden shed in the rear, 331/2 feet long, by 131/2 feet wide the whole in bad order. One Church two stories high, 85 feet long, 34 feet wide, & 18 feet high, with Brick floor and foundation, the whole out of repair. -

Reported in the Court of Special Appeals Of

REPORTED IN THE COURT OF SPECIAL APPEALS OF MARYLAND No. 1949 September Term, 1999 KENDRICK ORLANDO CHARITY v. STATE OF MARYLAND Moylan, Wenner, Byrnes, JJ. OPINION BY MOYLAN, J. Filed: June 8, 2000 If there is a lesson to be learned from this case, it is that when the police are permitted a very broad but persistently controversial investigative prerogative,1 they would be well advised, even when not literally required to do so, to exercise that prerogative with restraint and moderation, lest they lose it. In Whren v. United States, 571 U.S. 806, 116 S. Ct. 1769, 135 L. Ed. 2d 89 (1996), the Supreme Court extended law enforcement officers a sweeping prerogative, permitting them to exploit the investigative opportunities presented to them by observing traffic infractions even when their primary, subjective intention is to look for narcotics violations. The so-called “Whren stop” is a powerful law enforcement weapon. In utilizing it, however, officers should be careful not to attempt to “push out the envelope” too far,2 for if the perception should ever arise that ”Whren stops” are being regularly and immoderately abused, courts may be sorely tempted to withdraw the weapon from the law enforcement arsenal. Even the most ardent champions of vigorous law enforcement, therefore, would urge the police not to risk “killing the goose that lays the golden egg.” 1 See Whitehead v. State, 116 Md. App. 497, 500, 698 A.2d 1115 (1997). See also David A. Harris, Whren v. United States: Pretextual Traffic Stops and “Driving While Black,” The Champion, March 1997, at 41. -

Charity and Social Enterprise Update in Brief

Autumn 2013 Charity and Social Enterprise Update In brief Contents In the year since Lord Hodgson published his report on charity law there has been a lot of discussion about his recommendations but Charity law reform 3 so far, little action, report Rosamund McCarthy and Christine Rigby. Page 3 News in brief 5 Ban on TV campaigns 7 The European Court has upheld a UK ban on charity TV advertising for the purposes of campaigning and social advocacy. Email in governance 8 Lawrence Simanowitz advises that charities should not be deterred Skateistan 11 from campaigning by the decision. Page 7 CaSE Insurance 12 Tesse Akpeki and Christine Rigby outline the legal and governance Restricted funds 14 issues for boards to consider when communicating by email. Page 8 Companies Act update 16 Our client focus in this issue is on Skateistan, an international Focus on: Education 18 family of charities that provide skateboarding and educational programmes in Afghanistan and Cambodia. Page 11 Charity Commission update 22 It is important to view buying insurance for your charity or social enterprise as a vital aspect of your risk management rather than just another purchasing decision. Huw Evans of CaSE Insurance Front cover image: Skateistan outlines a good insurance-buying process. Page 12 BWB client Skateistan is an international family of charities that provide skateboarding The Charities Act 2011 provides some welcome relief for charities and educational programmes in Afghanistan struggling to use funds that appear to be locked away from use and Cambodia. For more information please with out of date purposes or restrictions.