Lake-Side Communities in Morris County, New Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Denville Trails Master Plan Is the Result of Significant Community Participation

Trails master plan FOR DENVILLE TOWNSHIP MORRIS COUNTY Denville Township Trails Master Plan Prepared by: Benjamin L. Spinelli, Principal Frank T. Pinto, Principal Bob Canace, Associate Kenneth Campbell, Licensed Drone Pilot Zenon Tech-Czarny, GIS Mapping Nick Nassiff, GIS Story Maps Genevieve Tarino, Specialist Intern Assistance Team: Brian Corrigan Griffin Lanel Rena Pinhas Jennifer Schneider Trail Blitz Day Team: Carol Mendez Briana Morales Rena Pinhas Jennifer Schneider Justin Singleton Greener by Design, LLC Township of Denville 94 Church Street, Suite 402 1 Saint Mary’s Place New Brunswick NJ 08901 Denville, NJ 07834 Phone: (732) 253-7717 Phone: (973) 625-8334 https://www.gbdtoday.com/ http://www.denvillenj.org July 1, 2018 i Acknowledgements Denville Township Trails Advisory Committee Thomas Andes (Mayor) AnnMarie Flake Christopher Golinski Kevin Loughran Stephanie Lyden (Council Liaison) Maryjude Haddock-Weiler Steven Ward (Administrator) Mayor and Township Council Thomas Andes (Mayor) Brian Bergen Blenn Buie Gary Borowiec Douglas N. Gabel Stephanie Lyden John Murphy Nancy Witte ii Denville Organizations and Offices Mayor and Council Township Administration Beautification Committee Trails Committee Recreation Department Outside Organizations Boy Scout Troop 118 Estling Lake Corp Jersey Off Road Bicycling Association Borough of Mountain Lakes Morris Area Freewheelers Morris County Park Commission Morris County Planning Board Morris County Municipal Utilities Authority New York-New Jersey Trail Conference Protect our Wetlands, Water -

LRM 9/27/01 Complete

Public Meeting of NEW JERSEY LAKE RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT ADVISORY TASK FORCE LOCATION: Borough Hall DATE: September 27, 2001 Mt. Arlington, New Jersey 11:00 a.m. MEMBERS OF TASK FORCE PRESENT: Senator Anthony R. Bucco (Vice-Chairman) Assemblyman Reed Gusciora Carmen Armenti Matthew Garamone Dirk C. Hofman John Hutchison III James E. Mumman Frances Smith Mark Smith John Terry ALSO PRESENT: James Requa (representing Martin Bierbaum) Zina M. Gamuzza Director of Communications Hearing Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey for Assemblyman Corodemus TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Anthony Albanese Chairman Lake Hopatcong Commission Mt. Arlington Borough, New Jersey 11 Arthur Crane representing Hibernia Fire Company Rockaway Township, New Jersey 12 Kenneth H. Klipstein Bureau Chief Division of Watershed Management New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection 20 Peter Rand Chairman Lake Arrowhead Club Denville, New Jersey 25 Charles Weldon representing Indian Lake Denville, New Jersey 30 Robert Caldo representing Cozy Lake Association Jefferson Township, New Jersey 31 Clifford R. Lundin, Esq. President Lake Hopatcong Protective Association Mt. Arlington Borough, New Jersey 33 John Inglesino Freeholder Morris County, New Jersey, and TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Mayor Rockaway Township, New Jersey 36 Joseph Nametko representing Lake Musconetcong Regional Planning Board Roxbury Township, New Jersey 38 Ronald Gatti Township Manager Byram Township, New Jersey 40 Schuyler Martin President Lake Swannanoa Sentinal Society Jefferson Township, New Jersey 43 Fred Suljic County Planning Director Division of Planning Sussex County, New Jersey 49 Senator Robert E. Littell District 24 52 mlc: 1-55 SENATOR ANTHONY R. -

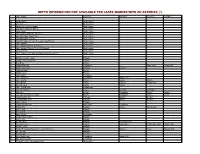

Depth Information Not Available for Lakes Marked with an Asterisk (*)

DEPTH INFORMATION NOT AVAILABLE FOR LAKES MARKED WITH AN ASTERISK (*) LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY GL Great Lakes Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin AL Dog River * Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Chambers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson AL Highland Lake * Blount AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Lake Gantt * Covington AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Jordan Elmore Coosa Chilton AL Lake Martin Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph AL Lay Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lay Lake and Mitchell Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lewis Smith Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Lewis Smith Lake * Cullman Walker Winston AL Little Lagoon Baldwin AL Logan Martin Lake Saint Clair Talladega AL Mobile Bay Baldwin Mobile Washington AL Mud Creek * Franklin AL Ono Island Baldwin AL Open Pond * Covington AL Orange Beach East Baldwin AL Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL Pickwick Lake Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Shelby Lakes Baldwin AL Walter F. -

Section-4.3.6-Flood.Pdf

Section 4.3.6: Risk Assessment ‐ Flood 4.3.6 Flood The following section provides the hazard profile (hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences and losses, probability of future occurrences, and impact of climate change) and vulnerability assessment for the flood hazard in Morris County. 2020 HMP Changes All subsections have been updated using best available data. The discussion of urban flooding has been expanded. Previous events between 2014 and 2019 are listed with a comprehensive list of previous events in Appendix E (Risk Assessment Supplement). The FEMA 2017 preliminary DFIRM was used to conduct the risk assessment. 4.3.6.1 Profile Hazard Description A flood is the inundation of normally dry land resulting from the rising and overflowing of a body of water. They can develop slowly over a period of days or develop quickly, with disastrous effects that can be local (impacting a neighborhood or community) or regional (affecting entire river basins, coastlines and multiple counties or states) (FEMA 2007). Floods are frequent and costly natural hazards in New Jersey in terms of human hardship and economic loss, particularly to communities that lie within flood-prone areas or floodplains of a major water source. The flood-related hazards most likely to impact Morris County are riverine (inland) flooding, urban flooding, and flooding as a result of a dam failure. Dam failure is discussed in Section 4.3.1 (Dam Failure). In addition, Morris County also experiences urban flooding which is the result of precipitation and insufficient drainage. Riverine (Inland) Flooding A floodplain is defined as the land adjoining the channel of a river, stream, ocean, lake, or other watercourse or water body that becomes inundated with water during a flood. -

Northern Highland American Legion State Forest

1 t 2 t 3 t 4 t 5 t 6 t 7 t 8 t 9 t 10 t 11 t 12 t 13 t 14 t 15 t 16 t 17 t 18 t 19 t 20 t 21 t 22 t 23 t 24 2 Jones Lake .................................G-19 Snipe Lake ................................. S-14 Black -90.05 River Index to Lakes/Rivers Judd Lake ....................................G-3 Snort Lake ..........................L10-M10 90.0667 - 46.3167 1 6 -90.0333 Map Legend S Junction Creek ...........................E-14 Snyder Lake ...............................N-22 D Razorback T D R R A Alder Lake ...................................K-9 Jute Lake ....................................H-19 South Bass Lake ......................... H-4 5 G O Ridges D T T G Northern Highland American Legion E EB R N Aldridge Lake ...........................W-16 Jyme Lake ....................................X-4 South Blue Lake.........................BB-3 I -90.0167 C Road Classifications Special Symbols H O I K Trail P A Alice Lake ....................................Z-2 Kasomo Lake ............................... S-8 South Branch OUS E H I K 46 C R I O C Allen Lake .................................. H-3 Kate Pier Creek ........................BB-10 Presque Isle River .............C11-E11 N-90 K 30 28 A 29 25 C 51 U.S. Highway Place of Interest Boat Access-Ramp T B Allequash Creek ........................N-16 Kate Pier Lake .........................BB-11 South Turtle Lake ........................ F-6 -89.9833 O R D RD Hobo LA K R Allequash Lake ..........................N-15 Kathan Creek ............................W-15 South Two Lakes....................... AA-6 O E D A M A Z Plum Lake U R Lake R State Highway Bike Trail Parking L Allequash Springs .....................N-17 Kathan Lake .......................V15-V16 Sparkling Creek .........................O-12 C P P Boat Access-Carry-In A O 70 D CLUBHOUSE R CK WARWI -89.9667 GOLF COURSE Alma Lake .................................U-12 Katherine Lake ........................... -

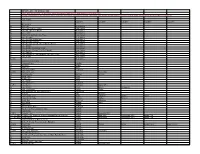

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F. -

US MAPS from Sketches by Theodore R

The Morristown Morris Township Library North Jersey History and Genealogy Center: Inventory of Maps and Surveys CALL NO. TITLE DATE SCALE SIZE DETAILS COPY NO. US MAPS From sketches by Theodore R. Davis; US-1-1 Bird's-eye view of Philadelphia 1872 Not given 32 x 23'' Copy 1 removed from Harper's Weekly 2/21/92. Sold by Tho. Basset in Fleet Street and US-1-2 A map of New England and New York 1650(?) 1" = 30 mi. 17"x21" Richard Chiswell in St. Paul's church Copy 1 Copy 2 yard. Text on reverse of Copy 1. A new and accurate map of the province of New York By J. Bew, Peter MasterRow. London. and part of the Jerseys, New England and Canada, US-1-3 1780 Not given 15"x11" Published as the Act Directs Oct 31st Copy 1 showing the scenes of our military operations during 1780. Original cloth backed. the present war; also the new erect state of Vermont New Netherlands, with a view of New Amsterdam (now US-1-4 1656 Not given 12" x 7" By A. Vander Donck. Copy 1 New York) Patroonships, manors and seigniories in New York US-1-5 [Rhode Island and Massachusetts] recognized the Order 1932 1" = 20 mi. 12"x8" By Max Mayer. Copy 1 of Colonial Lords of Manors United States, territories and insular possessions: Compiled from official surveys…Harry showing the extent of public surveys, Indian, military US-1-6 1899 Not given Not noted King, c.e. -- U.S. Dept of the Interior, Copy 1 and forest reservations, rail roads, canals and other General Land Office. -

Charted Lakes List

LAKE LIST United States and Canada Bull Shoals, Marion (AR), HD Powell, Coconino (AZ), HD Gull, Mono Baxter (AR), Taney (MO), Garfield (UT), Kane (UT), San H. V. Eastman, Madera Ozark (MO) Juan (UT) Harry L. Englebright, Yuba, Chanute, Sharp Saguaro, Maricopa HD Nevada Chicot, Chicot HD Soldier Annex, Coconino Havasu, Mohave (AZ), La Paz HD UNITED STATES Coronado, Saline St. Clair, Pinal (AZ), San Bernardino (CA) Cortez, Garland Sunrise, Apache Hell Hole Reservoir, Placer Cox Creek, Grant Theodore Roosevelt, Gila HD Henshaw, San Diego HD ALABAMA Crown, Izard Topock Marsh, Mohave Hensley, Madera Dardanelle, Pope HD Upper Mary, Coconino Huntington, Fresno De Gray, Clark HD Icehouse Reservior, El Dorado Bankhead, Tuscaloosa HD Indian Creek Reservoir, Barbour County, Barbour De Queen, Sevier CALIFORNIA Alpine Big Creek, Mobile HD DeSoto, Garland Diamond, Izard Indian Valley Reservoir, Lake Catoma, Cullman Isabella, Kern HD Cedar Creek, Franklin Erling, Lafayette Almaden Reservoir, Santa Jackson Meadows Reservoir, Clay County, Clay Fayetteville, Washington Clara Sierra, Nevada Demopolis, Marengo HD Gillham, Howard Almanor, Plumas HD Jenkinson, El Dorado Gantt, Covington HD Greers Ferry, Cleburne HD Amador, Amador HD Greeson, Pike HD Jennings, San Diego Guntersville, Marshall HD Antelope, Plumas Hamilton, Garland HD Kaweah, Tulare HD H. Neely Henry, Calhoun, St. HD Arrowhead, Crow Wing HD Lake of the Pines, Nevada Clair, Etowah Hinkle, Scott Barrett, San Diego Lewiston, Trinity Holt Reservoir, Tuscaloosa HD Maumelle, Pulaski HD Bear Reservoir, -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPS Fonn 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior prop name Mountain Lakes HD National Park Service county Morris, New Jersey National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ___)o!8 ____ Page lof28 Statement of Significance The proposed Mountain Lakes Historic District is distinguished among American residential communities in land use and landscape design. From its founding as a residential park, Mountain Lakes has integrated family living with man-made lakes, natural streams and springs, woodlands and wetlands. Dedicated parkland and undeveloped borough-owned lots contribute to spaciousness in both the proposed Mountain Lakes Historic District and the larger Borough. Throughout Mountain Lakes, forty percent of land is Borough-owned open space.1 At critical junctures in its history the Borough purchased additional undeveloped land to protect Mountain Lakes and the proposed district from intrusive development and to preserve its original design and character as a residential park. Mountain Lakes' ability to regulate its growth and maintain continuity in both landscape design and architecture has been characterized as unique in assessments of recent American city plauning.2 Its original housing stock- much of which remains today--was strongly influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement in the United States. By their location on natural rather than graded terrain, and, the use oflocal building materials, the Craftsman-influenced homes closely connect to nature and critically -

Watershed Stewardship Program Summary of Programs and Research 2011

Watershed Stewardship Program Summary of Programs and Research 2011 Adirondack Watershed Institute Watershed Stewardship Program Report # AWI 2012-01 2 Watershed Stewardship Program Summary of Programs and Research 2011 Table of Contents Dedication ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary and Introduction ...................................................................................................... 5 West Central Adirondack Region Summary ............................................................................................ 17 Watershed Stewardship Program- Staff Profiles .................................................................................... 24 Recreation Use Study: Cranberry Lake State Boat Launch ...................................................................... 30 Recreation Use Study: Fourth Lake State Boat Launch ........................................................................... 38 Recreation Use Study: Lake Flower State Boat Launch ........................................................................... 48 Recreation Use Study: Lake Placid State Boat Launch ............................................................................ 60 Recreation Use Study: Lake Placid Village Launch .................................................................................. 70 Recreation Use Study: Long Lake State Boat Launch ............................................................................. -

9.9 Township of Denville

Section 9.9 - Township of Denville 9.9 TOWNSHIP OF DENVILLE This section presents the jurisdictional annex for the Denville. The annex includes a general overview of the Township of Denville; an assessment of the Township of Denville’s risk, vulnerability, and mitigation capabilities; and a prioritized action plan to implement prior to a disaster to reduce future losses and achieve greater resilience to natural hazards. 9.9.1 Hazard Mitigation Planning Team The following individuals are the Township of Denville’s identified HMP update primary and alternate points of contact and NFIP Floodplain Administrator. Table 9.9-1. Hazard Mitigation Planning Team Primary Point of Contact Alternate Point of Contact Name / Title: Wesley Sharples, Emergency Manager Name / Title: John Ruschke, Engineer Address: 1 St. Mary’s Place Denville, NJ 07834 Address: 1 St. Mary’s Place Denville, NJ 07834 Phone Number: 973-627-4900 x368 Phone Number: 973-625-8300 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] NFIP Floodplain Administrator Name / Title: John Ruschke, PE, CFM Address: 1 St. Mary’s Place Denville, NJ 07834 Phone Number: 973-625-8300 Email: [email protected] 9.9.2 Jurisdiction Profile Denville Township is located in eastern Morris County. According to the U.S. Census, the Township has a total area of 12.64 square miles, of which 11.87 square miles is land and 0.77 square miles is water. It is bordered to the north by Rockaway Township, to the south by the Township of Parsippany-Troy Hills and Morris Township to the east by the Borough of Mountain Lakes and the Townships of Parsippany-Troy Hills and Boonton, and to the west by the Township and Borough of Rockaway and the Township of Randolph. -

2021-02-02 010515__2021 Stocking Schedule All.Pdf

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2021 Trout Stocking Schedule (as of 2/1/2021, visit fishandboat.com/stocking for changes) County Water Sec Stocking Date BRK BRO RB GD Meeting Place Mtg Time Upper Limit Lower Limit Adams Bermudian Creek 2 4/6/2021 X X Fairfield PO - SR 116 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 2 3/15/2021 X X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 4 3/15/2021 X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 GREENBRIAR ROAD BRIDGE (T-619) SR 94 BRIDGE (SR0094) Adams Conewago Creek 3 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 3 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 4 4/22/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 10/6/2021 X X Letterkenny Reservoir 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 5 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co.