Lady Gregory: "The Book of the People"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Holdings of Certain Lady Gregory Monographs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’S Rare Book Collection

Melissa A. Hubbard. An Analysis of the Holdings of Certain Lady Gregory Monographs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Rare Book Collection. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. December, 2007. 47 pages. Advisor: Charles B. McNamara This paper analyzes Lady Gregory monographs related to her work as a playwright and theater director. It includes biographical information about Lady Gregory and a description of how her materials relate to other Rare Book Collection holdings. The focus of the paper is an annotated bibliography of these titles, with detailed notes about the condition of the items held in the Rare Book Collection. The paper concludes with a desiderata and recommendations for continued development of the Lady Gregory collection. Headings: Gregory, Lady, 1852-1932 — Bibliography Special Collections — Collection Development University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Rare Book Collection. AN ANALYSIS OF THE HOLDINGS OF CERTAIN LADY GREGORY MONOGRAPHS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL’S RARE BOOK COLLECTION. by Melissa A. Hubbard A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina December 2007 Approved by _______________________________________ Charles B. McNamara 1 Table of Contents Part I Introduction 2 Biography 3 Collection Context 15 Methodology 16 Part II Annotated Bibliography 20 Collection Assessment 40 Desiderata 41 Table 1: Desiderata 42 Recommendations 43 Sources Consulted 44 2 Part I Introduction Lady Gregory was one of the most popular figures of the Irish literary renaissance, an early 20th century movement advocating the publication and promotion of literature that celebrated Irish culture and history. -

The Rendering of Irish Characters in Selected Plays by J.M. Synge Diplomarbeit

The Rendering of Irish Characters in Selected Plays by J.M. Synge Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Deborah SIEBENHOFER am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. phil. Martin Löschnigg Graz, 2010 I dedicate this thesis to my mother in profound gratitude for her endless patience, support, and encouragement. 1 Pastel drawing of J. M. Synge by James Paterson, 1906 And that enquiring man John Synge comes next, That dying chose the living world for text And never could have rested in the tomb But that, long travelling, he had come Towards nightfall upon certain set apart In a most desolate stony place, Towards nightfall upon a race Passionate and simple like his heart (W. B. Yeats, “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory”) 2 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.1. The Irish National Theatre ........................................................................................... 8 1.2. The Stage Irishman .................................................................................................... 12 1.2.1. The Stage Irishman up to the 19th Century ......................................................... 12 1.2.2. The 19th Century ................................................................................................ -

Lady Gregory 1881-1932, Undated MS.1995.028

Boston College Collection of Lady Gregory 1881-1932, undated MS.1995.028 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2783 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Boston College Collection of Lady Gregory MS.1995.028 - Page 2 - Summary Information Creator: Gregory, Lady, 1852-1932 Title: Boston College collection of Lady Gregory ID: MS.1995.028 Date [inclusive]: 1881-1932, undated Physical Description 0.25 Linear Feet (1 box) Language of the English Material: Abstract: This -

The Kiltartan History Book

The Kiltartan History Book Lady I. A. Gregory Project Gutenberg's The Kiltartan History Book, by Lady I. A. Gregory This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Kiltartan History Book Author: Lady I. A. Gregory Release Date: February 24, 2004 [EBook #11260] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE KILTARTAN HISTORY BOOK *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Garrett Alley, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THE KILTARTAN HISTORY BOOK. BY LADY GREGORY. ILLUSTRATED BY ROBERT GREGORY _BY THE SAME AUTHOR_ Seven Short Plays Cuchulain of Muirthemne Gods and Fighting Men Poets and Dreamers A Book of Saints and Wonders DEDICATED AND RECOMMENDED TO THE HISTORY CLASSES IN THE NEW UNIVERSITY CONTENTS The Ancient Times Goban, the Builder A Witty Wife An Advice She Gave Shortening the Road The Goban's Secret The Scotch Rogue The Danes The Battle of Clontarf The English The Queen of Breffny King Henry VIII. Elizabeth Her Death The Trace of Cromwell Cromwell's Law Cromwell in Connacht A Worse than Cromwell The Battle of Aughrim The Stuarts Another Story Patrick Sarsfield Queen Anne Carolan's Song 'Ninety-Eight Denis Browne The Union Robert Emmet O'Connell's Birth The Tinker A Present His Strategy The Man was Going to be Hanged The Cup of the Sassanach The Thousand Fishers What the Old Women Saw O'Connell's Hat The Change He Made The Man He Brought to Justice The Binding His Monument A Praise Made for Daniel O'Connell by Old Women and They Begging at the Door Richard Shiel The Tithe War The Fight at Carrickshock The Big Wind The Famine The Cholera A Long Remembering The Terry Alts The '48 Time A Thing Mitchell Said The Fenian Rising A Great Wonder Another Wonder Father Mathew The War of the Crimea Garibaldi The Buonapartes The Zulu War The Young Napoleon Parnell Mr. -

Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 The aW rped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J. Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, M. J.(2019). The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5278 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth By Martha J. Lee Bachelor of Business Administration University of Georgia, 1995 Master of Arts Georgia Southern University, 2003 ________________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Ed Madden, Major Professor Scott Gwara, Committee Member Thomas Rice, Committee Member Yvonne Ivory, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Martha J. Lee, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation and degree belong as much or more to my family as to me. They sacrificed so much while I traveled and studied; they supported me, loved and believed in me, fed me, and made sure I had the time and energy to complete the work. My cousins Monk and Carolyn Phifer gave me a home as well as love and support, so that I could complete my course work in Columbia. -

Augusta, Lady Gregory

Augusta, Lady Gregory From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Lady Gregory pictured on the frontispiece to "Our Irish Theatre: A Chapter of Autobiography" (1913) Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory (15 March 1852 – 22 May 1932), born Isabella Augusta Persse, was an Irish dramatist, folklorist and theatre manager. With William Butler Yeats and Edward Martyn, she co-founded the Irish Literary Theatre and the Abbey Theatre, and wrote numerous short works for both companies. Lady Gregory produced a number of books of retellings of stories taken from Irish mythology. Born into a class that identified closely with British rule, her conversion to cultural nationalism, as evidenced by her writings, was emblematic of many of the political struggles to occur in Ireland during her lifetime. Lady Gregory is mainly remembered for her work behind the Irish Literary Revival. Her home at Coole Park, County Galway, served as an important meeting place for leading Revival figures, and her early work as a member of the board of the Abbey was at least as important for the theatre's development as her creative writings. Lady Gregory's motto was taken from Aristotle: "To think like a wise man, but to express oneself like the common people."] Early life and marriage Lady Gregory was born the youngest daughter of the Anglo-Irish landlord family Persse at Roxborough, County Galway. Her mother, Frances Barry, was related to Standish O'Grady, 1st Viscount Guillamore, and her family home, Roxborough, was a 6,000-acre (24 km²) estate located between Gort and Loughrea, the big house of which was later burnt down during the Irish Civil War. -

Weekly Lists

Date: 15/07/2021 GALWAY COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 4:04:42 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S FURTHER INFORMATION RECEIVED/VALIDATED APPLICATIONS FROM 07/05/2021 To 07/11/2021 The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION NUMBER TYPE INVALID RECEIVED AND LOCATION 20/683 Udaras na Gaeltachta P 18/05/2021 F le haghaidh Chéim 1 den fhorbairt leanúnach ar an bpáirc nuálaíochta mara Páirc na Mara ar láithreán athfhorbraíochta a bhfuil limistéar foriomlán de thimpeall 9 heicteár i gceist leis. Tá limistéar de 25.2 heicteár i gceist le teorainn iomlán an iarratais. Tá roinnt áiseanna tionsclaíocha mhuirbhunaithe i gceist leis an bhforbraíocht, mar aon le háisteanna oideachais agus taighde i gCill Chiaráin, Contae na Gaillimhe sna bailte fearainn Cill Chiaráin, An Aird Mhóir agus Caladh Mhaínse. San áireamh san fhorbraíocht tá astarraingt uisce ó Loch Scainimh, é a aistriú chuig Loch an Iarainn agus a stóráil go sealadach inti, é a ghaibhniú agus a phumpáil chug láithreán Pháirc na Mara le príomhphíobán aníos. Is sna bailte fearainn Caladh Mhaínse agus Cill Chiaráin atá na hastarraingtí lonnaithe. Thug Comhairle Contae na Gaillimhe cead pleanála roimhe seo i leith gníomhaíochtaí dobharshaothrú-bhunaithe ar an láithreán iarratais ag Páirc na Mara in 2002 (Tagairt Pleanála: 01/2584) agus tógadh an chéad chéim den pháirc nuálaíochta in 2005. -

Aristotle's Bellows by LADY GREGORY

Aristotle's Bellows BY LADY GREGORY PERSONS The Mother. Celia (HER DAUGHTER). Conan (HER STEPSON). Timothy (HER SERVING MAN). Rock (A NEIGHBOUR). Flannery (HIS HERD). Two Cats. ACT I ACT I Scene: A Room in an old half-ruined castle. Mother: Look out the door, Celia, and see is your uncle coming. Celia: (Who is lying on the ground, a bunch of ribbons in her hand, and playing with a pigeon, looks towards door without getting up.) I see no sign of him. Mother: What time were you telling me it was a while ago? Celia: It is not five minutes hardly since I was telling you it was ten o'clock by the sun. 1 Mother: So you did, if I could but have kept it in mind. What at all ails him that he does not come in to the breakfast? Celia: He went out last night and the full moon shining. It is likely he passed the whole night abroad, drowsing or rummaging, whatever he does be looking for in the rath. Mother: I'm in dread he'll go crazy with digging in it. Celia: He was crazy with crossness before that. Mother: If he is it's on account of his learning. Them that have too much of it are seven times crosser than them that never saw a book. Celia: It is better to be tied to any thorny bush than to be with a cross man. He to know the seventy-two languages he couldn't be more crabbed than what he is. -

John Millington Synge (16 April 1871 – 24 March 1909) Was an Irish Writer

www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Premonition of Death in J.M.Synge’s Poetry D.S.Kodolikar Asso. Professor Department of English S.M.Joshi College, Hadapsar, Pune -28. Edmund John Millington Synge (16 April 1871 – 24 March 1909) was an Irish writer. He was a playwright, poet and lover of folklore. He was influenced by W.B.Yeats after meeting him and with his advice he decided to go to Aran Islands to prepare himself for further creative work. He joined W.B.Yeats, Lady Gregory, Augusta, and George William Russell to form the Irish National Theatre Society, which later was established as the Abbey Theatre.. He is best known for his play The Playboy of the Western World, which caused riots during its opening run at the Abbey Theatre. Synge was born in Newtown Villas, Rathfarnham, County Dublin on 16 April 1871.He was the youngest son in a family of eight children. His parents were part of the Protestant middle and upper class: Rathfarnham was rural part of the county, and during his childhood he was interested in ornithology. His earliest poems are somewhat Wordsworthian in tone. His poetry reflects his love for nature and the richness of the landscape. Synge was educated privately at schools in Dublin and later studied the musical instruments like piano, flute, violin. He was interested in music and his knowledge of music reflects in his poems. He wanted to make career in music but changed his mind and decided to focus on literature. -

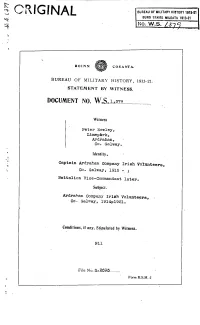

BMH.WS1379.Pdf

ROINN COSANTABUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,379 Witness Peter Howley, Limepark, Ardrahan, Co. Galway. Identity. Captain Ardrahan Company Irish Volunteers, Co. Gaiway, 1915 -; Battalion Vice-Commandant later. Subject. Ardrahan Company Irish Volunteers, Co. Galway, 1914-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2693 Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY PETER HOWLEY, Limepark, Ardrahan, Co. Gaiway. I was born in Limepark in the parish of Peterswell on the 12th April, 18914, and was educated at Peterswell National School until I reached the age of about sixteen years. I then left school and went to work on my father's farm at Limepark about the year 1910. At that time conditions were very unsettled in my part of County Galway. Holdings were small and rents were very high There were many evictions for non-payment of rent. The landlords had little mercy on the tenants who could not afford to pay the high rents, and evictions were carried out with the assistance of the R.I.C., a most unpopular force for that reason. I remember that in the year 1909 my four brothers were working on my uncle's farm at Capard. One evening on their way home to Limepark from capard they stopped at the village of Peterswell for refreshments. On leaving Hayes's publichouse one of my brothers saw an R.I.C. man with his ear to the door in a listening attitude. My brother struck him and he ran to the barrack, which my brothers had to pass on their way home. -

A Thesis Presented'to Thef~Culty of the Department of English Indiana

The Renaissance movement in the Irish theatre, 1899-1949 Item Type Thesis Authors Diehl, Margaret Flaherty Download date 06/10/2021 20:08:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/4764 THE :RENAISSANCE HOVEMENT IN THE IRISH THEATRE 1899... 1949 A Thesis Presented'to TheF~culty of the Department of English Indiana. state Teachers College >" , .. .I 'j' , ;I'" " J' r, " <>.. ~ ,.I :;I~ ~ .~" ",," , '. ' J ' ~ " ") •.;.> / ~ oj.. ., ". j ,. ".,. " l •" J, , ., " .,." , ') I In Partial Fulfillment of the ReqUi:tements for th.eDegree Mast~rofArts in Education by Margaret Flaherty' Diehl June- 1949 i . I .' , is hereby approved as counting toward the completion of the Maste:r's degree in the amount of _L hOUI's' credit. , ~-IU~~~....{.t.}.~~~f...4:~:ti::~~~'~(.{I"''-_' Chairman. Re:prese~ative of Eng /{Sh Depa~ent: b~~~ , ~... PI ACKf.iIUvJLJIDG.fI1:EThTTS The author of this thesis wishes to express her sincere thanks to the members of her committee: (Mrs.) Haze~ T. Pfennig, Ph.D., chairman; (Mrs.) Sara K. Harve,y, Ph.D.; George E. Smock, Ph.D., for their advice and assistance. She appreciates the opportunities fOr research "itlhich have been extended to her, through bo'th Indiana State Teachers College Librar,y and Fairbanks Memoria~ Librar,y. The writer also desires to thank Lennox Robinson and Sean a'Casey fOr their friendly letters" She is espeCially indebted for valuable information afforded her through correspondence with Denis Johnston. Margaret Flaherty Diehl TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I.. BEGINNING OF THE DRAMA IN IRELAND ••••• .. ". 1 Need for this study of the Irish Renaissance .. 1 The English theatre in Ireland • • e' • • " ." 1 Foupding of the Gaiety Theatre . -

Empire, Class, and Religion in Lady Gregory's Dramatic Works

‘The Return to the People’: Empire, Class, and Religion in Lady Gregory’s Dramatic Works Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Anna Pilz. July 2013 Anna Pilz University of Liverpool 2013 Abstract ‘The Return to the People’: Empire, Class, and Religion in Lady Gregory’s Dramatic Works Anna Pilz This thesis examines a selection of Lady Gregory’s original dramatic works. Between the opening of the Abbey Theatre in 1904 and the playwright’s death in 1932, Gregory’s plays accounted for the highest number of stage productions in comparison to her co-directors William Butler Yeats and John Millington Synge. As such, this thesis analyses examples ranging from her most well-known and successful pieces, including The Rising of the Moon and The Gaol Gate, to lesser known plays such as The Wrens, The White Cockade, Shanwalla and Dave. With a focus on the historical, bibliographical, and political contexts, the plays are analysed not only with regard to the printed texts, but also in the context of theatrical performances. In order to re-evaluate Gregory’s contribution to the Abbey, this thesis is divided into three chapters dealing with dominant themes throughout her career as a playwright: Empire, class, and religion. Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to the Institute of Irish Studies, University of Liverpool, for its financial support throughout my postgraduate studies. I am also indebted to the School of Histories, Languages and Cultures and the International Association for the Study of Irish Literatures for their financial assistance in covering travel costs to conferences and archives in the UK and abroad.