The Atlantic Railway Corridor the GALWAY–MAYO RAIL LINK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

ERT-Newslines-Feb-2013

NEWSLINES What's new this month Most timetables in this edition are valid until June 9, except where the accommodation conveyed on some night trains. shown. We are also including this month the first of this year's Summer The Espresso (E) train category has been discontinued with the last International Supplements, with advance versions of Tables 10 to 32 remaining trains reclassified as InterCityNotte (ICN). (also 47/49), valid from June 10. Next month the Supplement will be expanded to contain Tables 10 to 68, whilst the April and May editions SPAIN will contain Summer versions of all our International tables. As mentioned under the International heading, the Barcelona - Girona - CAR-CARRYING TRAINS Figueres high-speed line opened on January 9, reducing journey times by around 50 minutes. There are nine high-speed journeys each way as Further reductions have been made to services this summer. Most shown in Table 657. Eight of these are provided by extending existing notable is the loss of all international car-carrying trains serving Berlin, Madrid - Barcelona AVE trains to and from Figueres Vilafant. Three Firenze, Trieste and Verona. However, a new train is due to connect the fares are available between Barcelona and Figueres: Turista, Netherlands and Slovenia this summer when Euro-Express-Train- Preferente and Club (in Turista class the Avant level of fares apply charter introduces a weekly service from 's-Hertogenbosch to Koper, and trains carry both the AVE and AV classifications on this section of ideally situated for holidays in Istria or on the Adriatic coast, and also route). -

The Kiltartan History Book

The Kiltartan History Book Lady I. A. Gregory Project Gutenberg's The Kiltartan History Book, by Lady I. A. Gregory This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Kiltartan History Book Author: Lady I. A. Gregory Release Date: February 24, 2004 [EBook #11260] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE KILTARTAN HISTORY BOOK *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Garrett Alley, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THE KILTARTAN HISTORY BOOK. BY LADY GREGORY. ILLUSTRATED BY ROBERT GREGORY _BY THE SAME AUTHOR_ Seven Short Plays Cuchulain of Muirthemne Gods and Fighting Men Poets and Dreamers A Book of Saints and Wonders DEDICATED AND RECOMMENDED TO THE HISTORY CLASSES IN THE NEW UNIVERSITY CONTENTS The Ancient Times Goban, the Builder A Witty Wife An Advice She Gave Shortening the Road The Goban's Secret The Scotch Rogue The Danes The Battle of Clontarf The English The Queen of Breffny King Henry VIII. Elizabeth Her Death The Trace of Cromwell Cromwell's Law Cromwell in Connacht A Worse than Cromwell The Battle of Aughrim The Stuarts Another Story Patrick Sarsfield Queen Anne Carolan's Song 'Ninety-Eight Denis Browne The Union Robert Emmet O'Connell's Birth The Tinker A Present His Strategy The Man was Going to be Hanged The Cup of the Sassanach The Thousand Fishers What the Old Women Saw O'Connell's Hat The Change He Made The Man He Brought to Justice The Binding His Monument A Praise Made for Daniel O'Connell by Old Women and They Begging at the Door Richard Shiel The Tithe War The Fight at Carrickshock The Big Wind The Famine The Cholera A Long Remembering The Terry Alts The '48 Time A Thing Mitchell Said The Fenian Rising A Great Wonder Another Wonder Father Mathew The War of the Crimea Garibaldi The Buonapartes The Zulu War The Young Napoleon Parnell Mr. -

Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 The aW rped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J. Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, M. J.(2019). The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5278 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth By Martha J. Lee Bachelor of Business Administration University of Georgia, 1995 Master of Arts Georgia Southern University, 2003 ________________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Ed Madden, Major Professor Scott Gwara, Committee Member Thomas Rice, Committee Member Yvonne Ivory, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Martha J. Lee, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation and degree belong as much or more to my family as to me. They sacrificed so much while I traveled and studied; they supported me, loved and believed in me, fed me, and made sure I had the time and energy to complete the work. My cousins Monk and Carolyn Phifer gave me a home as well as love and support, so that I could complete my course work in Columbia. -

Weekly Lists

Date: 15/07/2021 GALWAY COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 4:04:42 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S FURTHER INFORMATION RECEIVED/VALIDATED APPLICATIONS FROM 07/05/2021 To 07/11/2021 The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION NUMBER TYPE INVALID RECEIVED AND LOCATION 20/683 Udaras na Gaeltachta P 18/05/2021 F le haghaidh Chéim 1 den fhorbairt leanúnach ar an bpáirc nuálaíochta mara Páirc na Mara ar láithreán athfhorbraíochta a bhfuil limistéar foriomlán de thimpeall 9 heicteár i gceist leis. Tá limistéar de 25.2 heicteár i gceist le teorainn iomlán an iarratais. Tá roinnt áiseanna tionsclaíocha mhuirbhunaithe i gceist leis an bhforbraíocht, mar aon le háisteanna oideachais agus taighde i gCill Chiaráin, Contae na Gaillimhe sna bailte fearainn Cill Chiaráin, An Aird Mhóir agus Caladh Mhaínse. San áireamh san fhorbraíocht tá astarraingt uisce ó Loch Scainimh, é a aistriú chuig Loch an Iarainn agus a stóráil go sealadach inti, é a ghaibhniú agus a phumpáil chug láithreán Pháirc na Mara le príomhphíobán aníos. Is sna bailte fearainn Caladh Mhaínse agus Cill Chiaráin atá na hastarraingtí lonnaithe. Thug Comhairle Contae na Gaillimhe cead pleanála roimhe seo i leith gníomhaíochtaí dobharshaothrú-bhunaithe ar an láithreán iarratais ag Páirc na Mara in 2002 (Tagairt Pleanála: 01/2584) agus tógadh an chéad chéim den pháirc nuálaíochta in 2005. -

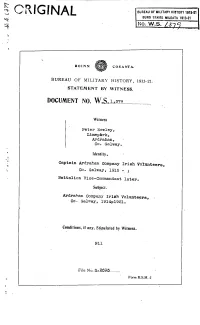

BMH.WS1379.Pdf

ROINN COSANTABUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,379 Witness Peter Howley, Limepark, Ardrahan, Co. Galway. Identity. Captain Ardrahan Company Irish Volunteers, Co. Gaiway, 1915 -; Battalion Vice-Commandant later. Subject. Ardrahan Company Irish Volunteers, Co. Galway, 1914-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2693 Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY PETER HOWLEY, Limepark, Ardrahan, Co. Gaiway. I was born in Limepark in the parish of Peterswell on the 12th April, 18914, and was educated at Peterswell National School until I reached the age of about sixteen years. I then left school and went to work on my father's farm at Limepark about the year 1910. At that time conditions were very unsettled in my part of County Galway. Holdings were small and rents were very high There were many evictions for non-payment of rent. The landlords had little mercy on the tenants who could not afford to pay the high rents, and evictions were carried out with the assistance of the R.I.C., a most unpopular force for that reason. I remember that in the year 1909 my four brothers were working on my uncle's farm at Capard. One evening on their way home to Limepark from capard they stopped at the village of Peterswell for refreshments. On leaving Hayes's publichouse one of my brothers saw an R.I.C. man with his ear to the door in a listening attitude. My brother struck him and he ran to the barrack, which my brothers had to pass on their way home. -

Annual Report 2005 1

Annual Report 2005 1 Annual Report 2005 © Department of Transport Department of Transport Transport House, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland Tel 01-6707444 Fax 01-6709633 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.transport.ie Copies of this report may be downloaded from www.transport.ie in pdf format. The Department may be contacted from any part of the country for the price of a local call by dialling 1890-443311 An Roinn Iompair Teach Iompair, Sráid Chill Dara, Baile Átha Claith 2, Éire Tel 01-6707444 Fax 01- 6709633 Rphoist: [email protected] Láithair Eangach: http://www.transport.ie Is féidir teangmhail a dhéanamh leis an Roinn ó aon pháirt den tír le haghaidh praghas glaoch áitiúil má dhiailionn tú 1890-443311 Annual Report 2005 Statement of the Minister It is my pleasure to introduce my 3 Department’s Annual Report for 2005 which reports on progress against our ambitious commitments and objectives set down in our most recent Statement of Strategy 2005-2007. Significant progress on implementing the Agreed Pass, Sligo Inner Relief Road, South Programme for Government has been made by Eastern Motorway section of M50. the Department in the course of 2005. The commencement of work on 15 other In 2005 my Department was given an projects including Dundalk/border on the extraordinary opportunity by Government: To M1, Arklow/Gorey Bypass on the N11 and prepare a plan to transform this country’s the Monaghan By Pass on the N2; transport network within a ten-year financial Major public transport developments framework. The opportunity was great, the including completion of the DART upgrade challenge immense but we met that challenge with project (extended platforms for 8 car trains, the launch, on 1 November, 2005 of the Transport accessibility improvements), entry into 21 project. -

Older People on the Global Agenda

AGE ACTION IRELAND Older People On The Global Agenda Education Pack February 2010 Acknowledgements This Education pack was produced by Annette Honan and designed by Claire Kehoe for Age Action Ireland. Age Action Ireland gratefully acknowledges the funding of Irish Aid. 2 Table of Contents FORWARD 4 SECTION 1 – Introductory Activities Ice breakers 5 Stereotyping and prejudice activities 8 Exclusion game 9 Matching rights activity 10 Summary version of Universal Declaration of Human Rights 13 SECTION 2 – Using the media to explore a topic Climate change activities 15 Irish flooding news clippings 18 Climate change case studies 29 Fact sheet on climate change 32 SECTION 3 – Taking a thematic approach Pensions not poverty 33 Activities 33 Case studies 33 Social Protection fact sheets 35 Health 38 Activities 42 Charades Cards 43 Role play cards 44 HIV/AIDS Ways of introducing HIV/AIDS 47 Case studies 48 Fact sheet – HIV and Older people: The untold story 51 Older people at work Activities 53 A case study from Peru – Older people on the alert 55 Working for change Looking at the Irish experience 57 Case studies from Kenya and Argentina 58 SECTION 4 – Resources Video links 61 Web links 61 3 FORWARD We are delighted to introduce this Education Pack designed for use by educators in the Development Education sector. The pack aims to facilitate an easy and interesting education process for both the educator and student. The pack has been produced as part of Age Action Ireland’s Global Education Programme and is the first of its kind in relation to Ageing. -

Reflections on Rent-Seeking in Ireland and Its Bus Industry

12 Barrett article.qxp_Admin 66-1 19/02/2018 17:40 Page 129 Administration, vol. 66, no. 1 (2018), pp. 129–146 doi: 10.2478/admin-2018-0012 Reflections on rent-seeking in Ireland and its bus industry Sean Barrett Economics Department, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland Introduction Rent-seeking is the lobbying of government in order to achieve tax reductions, subsidies and restrictions on competition. O’Leary (2015) has argued that the theory of rent-seeking has the potential for explaining Ireland’s long-term growth from the 1950s to the present day. This paper reflects on the destructive effects of rent-seeking in Ireland as a whole and in its bus industry in particular. The next section outlines the pervasiveness of the problem as set out in the Culliton report (1992). This is followed by a section considering rent- seeking in Irish transport in general and in the bus industry in particular before the 1980s. The following sections deal with developments in that industry from the 1980s to 2010, the impacts in the bus industry of the liberalisations following the Swords Express case in 2010, and the need for reforms in Ireland’s public institutions. The final section widens the discussion again to rent-seeking in other sectors in the present day. The pervasiveness of the problem The extent of rent-seeking in the Irish economy was noted in the Culliton report of 1992, which examined the causes of an under - 129 12 Barrett article.qxp_Admin 66-1 19/02/2018 17:40 Page 130 130 SEAN BARRETT performing economy at that time. -

Census 2011 – Results for County Galway

Census 2011 – Results for County Galway Population Results Social Inclusion Unit Galway County Council Table of Contents Page Summary 3 Table 1 Population & Change in Population 2006 - 2011 4 Table 2 Population & Change in Population 2006 – 2011 by Electoral Area 4 Figure 1 Population Growth for County Galway 1991 - 2011 5 Table 3 Components of Population Change in Galway City, Galway 5 County, Galway City & County and the State, 2006 - 2011 Table 4 Percentage of Population in Aggregate Rural & Aggregate Town 6 Areas in 2006 & 2011 Figure 2 Percentage of Population in Aggregate Rural & Aggregate Town 6 Areas in County Galway 2006 & 2011 Table 5 Percentage of Males & Females 2006 & 2011 6 Table 6 Population of Towns* in County Galway, 2002, 2006 & 2011 & 7 Population Change Table 7 Largest Towns in County Galway 2011 10 Table 8 Fastest Growing Towns in County Galway 2006 - 2011 10 Table 9 Towns Most in Decline 2006 – 2011 11 Table 10 Population of Inhabited Islands off County Galway 11 Map 1 Population of EDs in County Galway 2011 12 Map 2 % Population Change of EDs in County Galway 2006 - 2011 12 Table 11 Fastest Growing EDs in County Galway 2006 – 2011 13 Table 12 EDs most in Decline in County Galway 2006 - 2011 14 Appendix 1 Population of EDs in County Galway 2006 & 2011 & Population 15 Change Appendix 2 % Population Change of all Local Authority Areas 21 Appendix 3 Average Annual Estimated Net Migration (Rate per 1,000 Pop.) 22 for each Local Authority Area 2011 2 Summary Population of County Galway • The population of County Galway (excluding the City) in 2011 was 175,124 • There was a 10% increase in the population of County Galway between 2006 and 2011. -

Lot 1 Box of Irish Railway Interest Photographs Etc. Estimate

Purcell Auctioneers - Specialist Auction Of Irish Interest Books with dedicated section for Irish Railwayana Literature & Ephemera - Starts 13 Mar 2019 Lot 1 Box of Irish Railway Interest Photographs etc. Estimate: 40 - 60 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 2 Box of Irish Railway Interest Ephemera Estimate: 40 - 60 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 3 Box of Irish Railway Interest Ephemera Estimate: 30 - 50 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 4 Large Box of Mostly Non-Irish Railway Interest Books etc. Estimate: 20 - 40 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 5 Two Boxes of CIE Interest Ephemera, Ledgers etc. Estimate: 60 - 100 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 6 Irish Railwayana Scrap Book, tickets, correspondence, notices etc. Estimate: 50 - 100 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 7 Irish Railwayana Scrap Book, tickets, correspondence, notices etc. Estimate: 50 - 100 Fees: 20% inc VAT for absentee bids, telephone bids and bidding in person 23.69% inc VAT for Live Bidding and Autobids Lot 8 Irish Railwayana Scrap Book, County Donegal Railways, Northern Ireland Railways, Great Northern Railway Co. -

SENATOR LORRAINE HIGGINS KEEPING in TOUCH TUAM the Labour Party Summer 2015 a Note from Senator Lorraine Higgins Another Year Is Flying By

SENATOR LORRAINE HIGGINS KEEPING IN TOUCH TUAM The Labour Party Summer 2015 A note from Senator Lorraine Higgins Another year is flying by. As we pass the midway point it is good to reflect on the things achieved over the past few months. It has been a very busy time for my team and I and this is set to continue. Tuam is always on my agenda and I would like to take this opportunity to draw your attention to the local issues I’ve worked to address in recent times. FIGHTING TO HAVE ESTATES TAKEN IN CHARGE I was appalled to read about the plight of a number of housing estates in Tuam whose residents are seeking to be taken in charge by Galway County Council to no avail. Homeowners and tenants have been terribly let down and this simply cannot continue. I have raised the matter in the Seanad and will continue to fight until this issue is resolved to the benefit of residents. CHAMPIONING SOCIAL TUAM BABIES INQUIRY The tragedy of the Tuam Mother and Baby home is one that HOUSING INVESTMENT has moved us all. While the time in which these horrible Ireland’s social housing waiting lists urgently need to be events is past, as a community and as a society we still live tackled. I lobbied Minister for the Environment, Community with their effects today. and Local Government Alan Kelly to get the ball rolling on With a public inquiry on the horizon, I am calling on the social housing infrastructure locally. To this end, I am pleased Commission of Investigation to ensure that the work of said to report that 25 homes are to be developed at Weir Road, inquiry be based locally so that the community can get a Tuam at a cost of €4.2 million.