The Inside out Group Model: Teaching Groups in Mindfulness-Based Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stages of Group Development

Know! The Stages of Group Development The Search Institute has identified 40 Developmental Assets for Adolescents; Talking regularly positive qualities that influence youth development, helping them become caring, with kids about the responsible and productive adults. The more developmental assets a youth reports dangers of alcohol, having, the less likely he/she is to engage in risky behaviors, like drinking, smoking tobacco and other and using other drugs. Social Competencies (meaning personal choices & drugs reduces their risk of using. interpersonal skills) is one of eight asset categories that make up the 40 Developmental Assets. Research proves that the more personal skills youth have when interacting with Know! urges you to others and making decisions, the more likely they are to grow up healthy and drug-free. encourage other With the start of a new school year, chances are, your middle and high school students parents to join will be assigned group projects with peers they may not know, providing them excellent Know!. opportunities to practice and enhance their social skills. Sounds like fun to some, but challenges may quickly arise when bringing together students with different academic Click here for the styles and personalities. Know! Parent Tip Sign-Up Page. Teachers facilitating team work and parents wanting to encourage and support their children can benefit from knowing the stages of group development. In 1965, Know! is a psychologist Bruce Tuckman, created a model on group dynamics that still applies program of: today. Tuckman's Stages of Group Development are: Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing. It is believed that regardless of a group's members, purpose, goal, culture, location, demographics, etc., these four stages are universal. -

Department of Psychology 1

Department of Psychology 1 DEPARTMENT OF Psychology (PSY) PSY 126 – First Year Seminar 1 credit hour PSYCHOLOGY The First-Year Seminar provides students with a multidisciplinary experience in which they approach an issue or problem from the perspective of three different academic differences. The First-Year Department Objectives Seminar will consist of three 1-credit hour courses taken as co-requisites • To provide a general foundation in the various content areas of the in a single semester. The successful completion of all three courses field of Psychology; satisfies the General Studies LOPER 1 course requirement. Students may • to provide suitable preparation in methodology for students planning take the First-Year Seminar in any discipline, irrespective of their major or to attend graduate school; minor. Students admitted as readmit students or transfer students who • to provide a sound basis for enhanced understanding of self and transfer 18 or more hours of General Studies credit to UNK are exempt others; from taking a LOPER 1 course. • to prepare students for careers in human service areas and high PSY 188 – GS Portal 3 credit hours school teaching; Students analyze critical issues confronting individuals and society • to support other departments by offering courses applicable to other in a global context as they pertain to the discipline in which the Portal majors and minors. course is taught. The Portal is intended to help students succeed in their university education by being mentored in process of thinking critically For departmental assessment purposes, all students will be required to about important ideas and articulating their own conclusions. -

Connecting Chelford Newsletter April 2021

NEWSLETTER APRIL 2021 We are a FREE non-profit making Befriending Service across Chelford and the immediate area. Our aim is to support people who may benefit from additional contact from local community befriending volunteers. Connecting Chelford was set up in April 2018 to deliver a volunteer befriending service which could support people who may feel isolated, lonely, vulnerable or in need of help. We are a formally constituted group of volunteers, with a committee supported by Chelford Surgery, St John’s Church and Chelford Together. Our volunteers helping with the The Reverend Fiona Robinson explains “During the last 12 months we have been living COVID Vaccine. in extremely unusual times and the friendships and support links, which are a core part of the Connecting Chelford ethos, have had to evolve to meet the strict Corona Virus restrictions and to keep our Befrienders and Befriendees safe. We have been proud that alternative ways have been found, such as outdoor visits, walks, regular phone calls, supporting appointments, shopping, collecting prescriptions and helping celebrate events. All of this has enabled us to continue to regularly support our friends. Our volunteers have also helped the professionals in delivering the flu vaccine and more recently the COVID vaccine. You may recognise a few faces. Card making when we We are extremely pleased to see the neighbourhood spirit that has blossomed to could all sit together. provide additional support within the community. As Chair of Connecting Chelford, I would like to thank all those involved within this network and especially our Coordinators, Barbara Wilson and Patsy Howlett who ensure that our friendships are well managed, well matched and activities delivered in a safe and happy environment. -

Groupwork Practice for Social Workers

Groupwork Practice for Social Workers 00_Crawford_Price_BAB1407B0153_Prelims.indd 1 11/11/2014 7:36:56 PM 1 INTRODUCING GROUPWORK Chapter summary In this chapter you will learn about • the overall purpose, aims, scope and features of this book • how the book is structured and the brief contents of each chapter • how the book is aligned with a range of national standards and requirements related to professional social work education and practice • the key themes that underpin the whole book • the range of terms, words and phrases used to describe groupwork INTRODUCTION Groups are the basic expressions of human relationships; in them lies the greatest power of man. To try to work with them in a disciplined way is like trying to har- ness the power of the elements and includes the same kind of scientific thinking, as well as serious consideration of ethics. Like atomic power, groups can be harmful and helpful. To work with such power is a humbling and difficult task. (Konopka, 1963: vii–viii) Social work practitioners work with groups of people in many different ways and in many different contexts. Whilst some of the wording in the above quotation may reflect the date it was written, some fifty years ago, it powerfully reflects the com- plexity of challenges and opportunities that may arise in contemporary groupwork practice. This book sets out to help you, the reader, understand and develop the knowledge, skills and values that are required to practise effectively in this complex 01_Crawford_Price_BAB1407B0153_Ch 01 Part I.indd 3 11-Nov-14 4:08:59 PM 4 GROUPWORK PRACTICE FOR SOCIAL WORKERS context. -

Supervising Child Protective Services Caseworkers

CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT USER MANUAL SERIES U.S. Depanment of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Administration on Children, Youth and Families Children's Bureau Office on Child Abuse and Neglect Supervising Child Protective Services Caseworkers Marsha K. Salus 2004 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Administration on Children, Youth and Families Children’s Bureau Office on Child Abuse and Neglect This page is intentionally left blank Table of Contents PREFACE ......................................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................3 1. PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................5 2. THE NATURE OF CHILD PROTECTIVE SERVICES SUPERVISION ................................7 Building and Maintaining the Foundation for Unit Functioning ..............................................7 Developing and Maintaining Individual Staff Capacity ............................................................8 Developing an Effective Relationship with Upper Management ................................................8 The Components of Supervisory Effectiveness............................................................................8 Supportive Supervisory Practices ..............................................................................................10 -

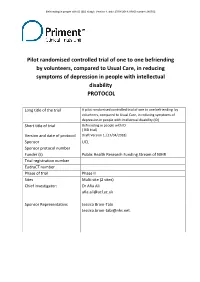

Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of One to One Befriending by Volunteers, Compared to Usual Care, in Reducing Symptoms of Depre

Befriending in people with ID (BID study); Version 1, date 27/04/2018; IRAS number 240552 Pilot randomised controlled trial of one to one befriending by volunteers, compared to Usual Care, in reducing symptoms of depression in people with intellectual disability PROTOCOL Long title of the trial A pilot randomised controlled trial of one to one befriending by volunteers, compared to Usual Care, in reducing symptoms of depression in people with intellectual disability (ID) Short title of trial Befriending in people with ID ( BID trial) Version and date of protocol Draft Version 1, [27/04/2018] Sponsor UCL Sponsor protocol number Funder (s) Public Health Research Funding Stream of NIHR Trial registration number EudraCT number Phase of trial Phase II Sites Multi site (2 sites) Chief investigator: Dr Afia Ali [email protected] Sponsor Representative: Jessica Broni-Tabi [email protected]. SIGNATURES The undersigned confirm that the following protocol has been agreed and accepted and that the Chief Investigator agrees to conduct the trial in compliance with the approved protocol and will adhere to the principles of GCP the Sponsor’s SOPs, and other regulatory requirements as amended. I agree to ensure that the confidential information contained in this document will not be used for any other purpose other than the evaluation or conduct of the clinical investigation without the prior written consent of the Sponsor. I also confirm that I will make the findings of the study publically available through publication or other dissemination tools without any unnecessary delay and that an honest accurate and transparent account of the study will be given; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned in this protocol will be explained. -

A Structural Approach to Four Theories of Group Development

3-7? A STRUCTURAL APPROACH TO FOUR THEORIES OF GROUP DEVELOPMENT DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Dennis J. King, B.S., M.L.A., M.Ed. Denton, Texas May, 1997 fin ~ //1 ^Pf- 3-7? A STRUCTURAL APPROACH TO FOUR THEORIES OF GROUP DEVELOPMENT DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Dennis J. King, B.S., M.L.A., M.Ed. Denton, Texas May, 1997 fin ~ //1 ^Pf- King, Dennis J, A structural approach to four theories of group development. Doctor of Philosophy (Counseling and Student Services), May, 1997, 84 pages, 14 figures, references, 72 titles. The goal of this study was to attempt to develop a classification scheme that systematically related individual behavior, interpersonal behavior, and group interactions for the purpose of using the resulting classification scheme to evaluate theories of group development proposed by Bion, Bennis and Shepard, Bales, and Tuckman and Jensen. It was assumed that theorists' presuppositions about the structure of groups might influence their theories. Using a qualitative process of analysis, a structural classification scheme (SCS) was developed based upon transformative and generative rules, utilizing the General System Theory subsystem process of self-regulated boundary operations. The SCS protocol was employed to categorize and compare the theories of group development proposed by Bion, Bennis and Shepard, Bales, and Tuckman and Jensen. The resulting categorization of theories indicated that relationships existed among and between a group's structural properties, the complexity and type of communication connections among and between group members, and the size of the group. -

2002 2002 - 2003 Bulletin Loma Linda University

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works School of Allied Health Professions Bulletins Catalogs and Bulletins 10-30-2002 2002 - 2003 Bulletin Loma Linda University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/sahp_bulletin Recommended Citation Loma Linda University, "2002 - 2003 Bulletin" (2002). School of Allied Health Professions Bulletins. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/sahp_bulletin/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Catalogs and Bulletins at TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Allied Health Professions Bulletins by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY L OMA L INDA U NIVERSITY ❦ School of Allied Health Professions D A • U N N I V I E 2 L • R S A I M T 0 Y O L T O E MAKE MAN WHO L 0 2 ❦ SCHOOL OF ALLIED HEALTH PROFESSIONS 2 0 2002 ❦ 2003 T O E MAKE MAN WHO L 0 School of Allied Health Professions 3 This BULLETIN is the definitive state- ment of the School of Allied Health Professions on the requirements for admission, enrollment, curriculum, and graduation. The School of Allied Health Professions reserves the right to change the requirements and policies set forth in this BULLETIN at any time upon rea- sonable notice. In the event of conflict between the statements of this BULLETIN and any other statements by faculty or administration, the provisions of this BULLETIN shall control, unless express notice is given that the BULLETIN is being modified. -

Community Capacity Building and Carer Support End of Year Report - 2018/2019

1 Community Capacity Building and Carer Support End of Year Report - 2018/2019 Date: May 2019 Period Covered: 1st April 2018 – 31st April 2019 Author: Jacqui Melville Contact: Jacqui Melville [email protected] 2 CONTENTS Introduction Background Quantative Outcomes Delivery Update Strategic Update Conclusion and Analysis Next Steps Recommendations List of Appendices 1 Organogram 2 Budget 3 Outcomes by Theme 4 Outputs by Theme 5 LAP Spend 7 Case Studies 3 INTRODUCTION Community Capacity Building and Carer Support (CCB&CS) is Health and Social Care North Lanarkshire’s Third Sector delivery branch (structure included as appendix 1). Through the CCB&CS Strategy the Third Sector’s contribution is co-ordinated, robustly monitored and works to the regional logic model based on a series of programme outcomes. The CCB&CS work is based on co-production (which includes co-commissioning at a community level); giving people choice and control and connecting people to their communities. Using nine thematic leads to guide best practice and 6 locality host organisations to ensure a truly community led approach, a devolved budget of £1.14 million is directly invested in organisations and community groups with countless others receiving support from other means. Investment ranges from micro-investment and matched funds to strategic investment in thematics of up to £75,000. Our programme approach ensures that all activity links to programme outcomes and that best value is achieved. Additionally, the programme is able to use its budget to leverage a significant although variable amount of additional funding and in-kind contributions. In 2018/2019 a conservative estimate of in-kind of contributions totalled £62,775 with £485,000 additional income leveraged. -

Deck Plate Leadership Series Group Development

Deck Plate Leadership Series Group Development USCG Leadership Competency: Leading Others: Team Building Learning Outcomes: • Describe the five states of group development • Assess what stage the flotilla or division is at. Time Required: 25 – 60 minutes depending on which slide option is chosen. A group is defined as a collection of two or more interacting individuals with a stable pattern of relationships who share common goals and who perceive themselves as being a group. Facilitator Activities: Present sides, providing amplifying information from material below. Facilitate discussion with last slide – Where are We as a Flotilla? Slides can be copied three-to-a- page with line for notes if projector is not available. Lesson Out Brief: Knowing the stage a group is in allows the leader to adjust their leadership approach. Forming – high task direction low member support; Storming - a balance between both high task direction and high member support; Norming – low task direction high member support; and, Preforming – a balance between both low task direction and low member support. This approach can also be individualized for members that are not involved in flotilla activities. Lesson Summary: Forming - High dependence on Flotilla Commander for guidance and direction. Little agreement on Flotilla aims other than received from leader. Member roles and responsibilities are unclear. Leader must be prepared to answer lots of questions about the Flotillas purpose, objectives and external relationships. Leader directs. Storming - Decisions don't come easily within Flotilla. Members vie for position as they attempt to establish themselves in relation to other members and the leader, who might receive challenges from members. -

Teams and Groups Outcomes Student Leader Learning Outcomes (SLLO) Project

Teams and Groups Outcomes Student Leader Learning Outcomes (SLLO) Project Definition Of Group or Team: Group of people who need each other to accomplish a result Interdependence Transcend the individual Shared purpose, goals, and values Tuckman Model of Team Development: Taken from: http://www.ncsu.edu/csleps/leadership/Group%20Develoment%20-%20Tuckman.pdf • Stage 1: Forming- The team meets and learns about the opportunity and challenges, and then agrees on goals and begins to tackle the tasks. Team members tend to behave quite independently. They may be motivated but are usually relatively uninformed of the issues and objectives of the team. Team members are usually on their best behavior but very focused on themselves. Mature team members begin to model appropriate behavior even at this early phase. The forming stage of any team is important because in this stage the members of the team get to know one another and make new friends. This is also a good opportunity to see how each member of the team works as an individual and how they respond to pressure. • Stage 2: Storming- Every group will then enter the storming stage in which different ideas compete for consideration. The team addresses issues such as what problems they are really supposed to solve, how they will function independently and together and what leadership model they will accept. Team members open up to each other and confront each other's ideas and perspectives. The storming stage is necessary to the growth of the team. It can be contentious, unpleasant and even painful to members of the team who are averse to conflict. -

Public Consultations Template

Public Involvement Update Report Engagement & Participation Committee - February 2017 Contents page/s Multicultural Health and Wellbeing Forum 3 - 7 ‘Breaking the Silence’ – Domestic Violence in a Faith Context 3 Mindfullness Monday 5 Ethnic Minority Forum (EMF) – ‘Spotlight on the Polish Community’ 6 Holocaust Memorial Day 6 Multicultural Movie Night 7 Integration of Health and Social Care, Aberdeen City 8 - 11 ABCD Seaton Event 8 Continuing our ABCD Story 9 Aberdeen West Locality Leadership Group 9 Modernising Primary Care 10 Adult Mental Health Service Redesign 11 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Keith and Speyside Pathfinder Project 12 Scottish Health Council Review 12 Monitoring of Cleaning Services 13 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The Baird Family Hospital and The ANCHOR Centre 13 - 15 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ViewPoint 16 Move of the ENT Head and Neck Outpatient Department and Audiology and Hearing Aid Services to Woodend Hospital 16 Revised map of the Woodend Hospital site 16 Primary Care: 16 Pre-application joint public consultation on a proposal to open a new community in Pitmedden 16 Changes at Northfield and Mastrick Medical Practice 17 An Caorann Medical Practice 17 Review of dispensing GP practices 18 Acute Care 18 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------