Oputa, Ebele Rose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

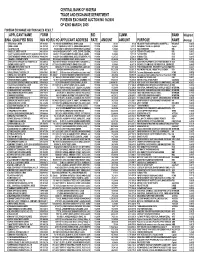

Foreign Exchange Auction No 10/2005 of 09Th February, 2005 Foreign Exchange Auction Sales Result Applicant Name Form Bid Cumm

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO 10/2005 OF 09TH FEBRUARY, 2005 FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION SALES RESULT APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK Weighted S/N A. QUALIFIED BIDS M/A NO R/C NO APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT AMOUNT PURPOSE NAME Average 1 KINGTOWN INVESTMENT LTD MF0694666 RC 219263 BLOCK 4 SHOP 25 AGRIC MARKET ODUN - 133.1000 35,035.56 35,035.56 123.171MT OF BOND PAPER IN SHEETS ACB 0.0488 2 OK SWEETSCO. MF0655935 66667 7A, ILASAMAJA SCHEME ITIRE LAGOS 133.1000 5,520.00 40,555.56 FOOD FLAVOURING, SPICY GINGER NBM 0.0077 3 GOLDNER GERHARD AA0438175 P04087933 PLOT 10, PROF JUBRIL AMINU STREET, PAR 133.0500 9,845.00 50,400.56 PERSONAL HOME REMMITTANCE GUARANTY 0.0137 4 OLIVER CHRISTIAAN RICHARD AA0697674 P03453293 PLOT 10, BLOCK 44, RAFIU BABATUNDE TIN 133.0500 6,660.00 57,060.56 PERSONAL HOME REMMITTANCE GUARANTY 0.0093 5 INSIS LIMITED MF0798353 RC291160 3 ARE AVENUE, BODIJA IBADAN 133.0100 21,052.00 78,112.56 SUPER AGRO-16 SPRAYER ECO 0.0293 6 ACCAT NIGERIA LIMITED MF0648716 376203 8 REVIVAL CLOSE OFF COCOA INDUSTRIES 133.0000 190,400.00 268,512.56 I UNIT COMMUNICATION TOWER INTERCON. 0.2652 7 AFRICAN AGRO PRODUCTS LTD. MF0487072 RC 391026 37, NIGER STREET, KANO 133.0000 39,000.00 307,512.56 ENDOSULFAN (AGRICULTURAL INSECTICIDES) INDO 0.0543 8 AK-TEL ELEKTRO LIMITED MF0659268 69171 272, IKORODU ROAD, LAGOS. 133.0000 67,808.00 375,320.56 10,320 SETS OF 33KV PIN INSULATOR COMPLETE. -

2009 Annual Report.Cdr

2009 Annual Report and Vision, Mission Statement and Values Financial Statements COSTAIN VALUES We are Customer focused Open and honest Safe and environmentally aware Team players Accountable Improving continuously and so the Natural choice Vision To be the leader in the delivery of sustainable engineering and construction solutions that meet our customers' needs. Mission Seen as an automatic choice for projects requiring innovation, initiative, teamwork and managerial skills. Objectives To develop a sustainable business through growth, which delivers profitability to our shareholders, value to our customers and a rewarding career for our staff. Strategy To have skilled teams committed to a common management system using tools and guides to provide a consistent approach to best practice and best value. 01 2009 Annual Report and Contents Financial Statements PAGE Company Profile.................................................................................................................................03 Directors, Officers and Professional Advisers......................................................................................05 The Board of Directors...................................................................................................................... .06 Results at a Glance.............................................................................................................................08 Notice of Annual General Meeting........................................................................................................09 -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts may not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the copyright owner. Center for Research Libraries Identifier: f-n-000001 Downloaded on: Jul 24, 2018, 4:11:33 AM / ) ■ ¥ 10 .i* Coi 1969 i Federal RepubKc of Nigeria Official Gazette . 3. No. 66 LAGOS-19th September, 19d8 Yoh 55 I CONTENTS Page Page Central Bank of Nigeria—Return of Assets M ovements of O fficers • • 1248-53 and Liabilities as at the close of Business Transfer of Federal Government Officers to on 31st August, 1968 • » • • f • • 1266 the Lagos State Government • • 1254-60 Loss of Local Purchase Orders « • • • 1266 Appointment of a Notary Public .. 1261 Award of Scholarships for 1968-69 Academic Session • • • • • • * • » 1266-8 Registration as a Notary Public • « • • 1261 Scholarship Awards under the Nigerian Gulf Addition to the List of Notaries Public • « 1261 Oil Company Training Fund • • 1268-9 Grant of Pioneer Certificate . -

Le Telecomunicazioni Nei Paesi in Via Di Sviluppo: Sfide E Opportunità Di Crescita

Le telecomunicazioni nei Paesi in via di sviluppo: sfide e opportunità di crescita Mario Marchese Università di Genova Genova, 06/11/2015 Indice Evoluzione di Internet “Digital Divide” Nanosatelliti Benefici dell’interconnessione Telefoni mobili Case studies – Africa – Nigeria, Ghana, Togo, Senegal Genova, 06/11/2015 Statistiche Statistiche di Internet (milioni di utenti) – 3,270,490,584 – 30 giugno 2015 http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm Genova, 06/11/2015 Statistiche Internet (2008) WORLD INTERNET USAGE AND POPULATION STATISTICS Usage Internet % Population Usage Gro Population Internet Users Usage, ( % of wth World Regions ( 2008 Dec/31, Latest Penetrati Worl 2000 Est.) 2000 Data on ) d - 2008 Africa 955,206,348 4,514,400 51,065,630 5.3 % 3.5 % 1,031.2 % Asia 3,776,181,949 114,304,000 578,538,257 15.3 % 39.5 % 406.1 % Europe 800,401,065 105,096,093 384,633,765 48.1 % 26.3 % 266.0 % Middle East 197,090,443 3,284,800 41,939,200 21.3 % 2.9 % 1,176.8 % North America 337,167,248 108,096,800 248,241,969 73.6 % 17.0 % 129.6 % Latin America/Caribbean 576,091,673 18,068,919 139,009,209 24.1 % 9.5 % 669.3 % Oceania / Australia 33,981,562 7,620,480 20,204,331 59.5 % 1.4 % 165.1 % WORLD TOTAL 6,676,120,288 360,985,492 1,463,632,361 21.9 % 100.0 % 305.5 % Genova, 06/11/2015 Statistiche Internet (fine 2011) Genova, 06/11/2015 Statistiche Internet (giugno 2015) Genova, 06/11/2015 Internet per Aree Geografiche - 2008 Genova, 06/11/2015 Internet per Aree Geografiche - 2011 Genova, 06/11/2015 Internet per Aree Geografiche - 2015 Genova, 06/11/2015 -

Individual Licence Register Private Network Link (Pnl) Regional/ National

INDIVIDUAL LICENCE REGISTER PRIVATE NETWORK LINK (PNL) REGIONAL/ NATIONAL S/N NAME/ADDRESS OPERATIVE DATE EXPIRY DATE 1. Cyancom Limited 1st April 2012 30th March 2022 (Formerly MTS First Wireless Ltd) 8th Floor, Mulliner Towers, 39, Alfred Rewane Road, Ikoyi, Lagos. 2. Disc Communications Ltd 1st October, 2002 30 th September 2012 Lateef Jakande Road, Agidingbi, Ikeja, Lagos 3. Galaxy Information Technology & Telecommunications Ltd 1st September 2004 31 st August 2014 61, Ademola Adetokunbo Crescent, Wuse II, Abuja. 4. LT Mobile Nigeria Limited (formerly Linkserve Nig Ltd) 1st July 2005 30 th June 2015 Plot 308, Adeola Odeku Street, Victoria Island, Lagos 5. Integrated Communications Ltd 1st July 2005 30 th June 2015 Plot 1309, Parakou Crescent, Wuse II, Abuja 6. Rainbownet Limited 1st October 2005 30 th September 2015 Ebeano Estate, Independence Layout, Enugu. 7. Lakes Communications Ltd 1st November 2005 31 st October 2015 Tofa House, 1 st Floor, Plot 770, Central Business District, Abuja 8. Lakes Communications Ltd 1st January 2006 31 st December 2015 Tofa House, 1 st Floor, Plot 770, Central Business District, Abuja 9. Dott Telecommunications Ltd 1st February 2006 31 st January 2016 22, Mabiaku Road, GRA, Warri, Delta State 1 10. Independent Telephone Networks Limited 1st May, 2006 30 th April, 2016 26, Isaac John Street, G. R. A. Ikeja, Lagos. 11. Jap Telecommunications Nig Ltd 1st June 2006 31 st May 2016 Plot 25, Nelson Mandela Street, Asokoro, Abuja 12. Jenerich Communications Ltd 1st July 2006 30 th June 2016 154, Monrovia Street- Wuse II, Behind M-TEL Abuja 13. TC Africa Telecoms Networks Limited Block 1, Plot 13, Idigedu, 1st March 2007 28 th February 2017 Oyo State 14. -

Foreign Exchange Auction No 16/2005 of 02Nd March, 2005 Foreign Exchange Auction Sales Result Applicant Name Form Bid Cumm

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO 16/2005 OF 02ND MARCH, 2005 FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION SALES RESULT APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK Weighted S/NA. QUALIFIED BIDS M/A NO R/C NO APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT AMOUNT PURPOSE NAME Average 1 TECHNICO LIMITED MF 0629437 RC 91224 87A MARINE ROAD APAPA LAGOS 133.0500 367.03 367.03 MELAMINE FACED CHIPBOARDS (SHORTFALL RELIANCE 0.0006 2 FIDEL KENINE AA 1027523 A 1272719 BLOCK E, PLOT 10, GOOD HOMES ESTATE, A 133.0000 2,000.00 2,367.03 PERSONAL TRAVEL ALLOWANCE Capital 0.0033 3 ALUFOILS LTD MF-0646203 RC82064 KM 32 ABEOKUTA EXPRESSWAY ALAGBADO 133.0000 7,750.00 10,117.03 FOIL REWINDERS DBL 0.0129 4 OGBULIE, OBED NNODIM AA1212765 A0407946 BLOCK N, FLAT 1, SHEEL ESTATE, EDJEBA, 133.0000 150.00 10,267.03 FEES IFO ETS-GRE EXAM DBL 0.0002 5 CAPT ISAIAH OLADAPO SOKEYE (SAMUEL O. AA1391195 A0056211 1/5 DAPO SOKEYE CLOSE, ISOLO, LAGOS 133.0000 3,050.00 13,317.03 TUITION FEES ECO 0.0051 6 ENE THEODORE NWAMALA (ENE IKENNA N.) AA0967340 A1925141 38 OLOIBIRI ROAD, SHELL RESIDENTIAL AR 133.0000 12,207.25 25,524.28 SCHOOL FEES ECO 0.0203 7 HAGEN & COMPANY LIMITED BA050/2004210 RC343964 38/40 BURMA ROAD, APAPA, LAGOS 133.0000 43,240.00 68,764.28 CERAMIC TILES ECO 0.0719 8 THE UNITED AFRICAN INS. BROKERS LTD AA1006926 RC210035 33B BODE THOMAS STREET, SURULERE, LA 133.0000 14,703.42 83,467.70 QUARTERLY SUPPORT & DEV. -

2006 Annual Report and Accounts

Our Vision “To be the undisputed leading and dominant financial services institution in Africa.” Our Mission “To be a role model for African businesses by creating superior value for all our stakeholders, abiding by the utmost professional and ethical standards, and by building an enduring institution.” UBA Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2006 Core Values Humility Synonymous with meekness and a belief that the Customer is King, Our products and services cover every segment of the market, and at UBA, staff are taught not to despise small beginnings. By a deliberate business philosophy, numerous start-ups and new business initiatives have been supported from incubation to maturity. We treat our clients with respect and consideration, regardless of the size of their business. Empathy Knowledge of the customer and intimate understanding of their businesses is an integral part of the Group's marketing strategy, and this is done with a view to developing mutually beneficial and enduring relationships. We are constantly driven by a strong desire to assist our customers in their efforts to create value. Integrity Every member of the UBA group is taught to uphold the virtues of moral excellence, honesty, wholeness and sincerity in all interactions with customers, service providers, fellow staff and all other stakeholders. As a corporate we seek to uphold the utmost ethical standards in all our dealings. This value has proven tremendously helpful in building the UBA brand. Resilience It is part of the culture in UBA to proactively conceptualize and develop products and services which surpass the expectations of customers, no matter the odds. -

Individual Licence Register Internet Services

INDIVIDUAL LICENCE REGISTER INTERNET SERVICES S/NO NAME / ADDRESS OPERATIVE DATE EXPIRY DATE 1. Wesa Globalnet Limited 1st July, 2007 30 th June, 2012 (formerly issued to Wesa Comserve International Limited) 4A, Parana Close, Off Mississippi Str, Maitama, Abuja 2. Voix Networks Limited 1st July, 2007 30 th June, 2012 Plot 1100, Kolda Link Street, Wuse II, Abuja 3. Foris Telecom (Nig) Ltd 1st July, 2007 30 th June, 2012 Suite D4, Sheriff Plaza, Wuse II, Abuja 4. NOL Freedom Limited 1st July, 2007 30 th June, 2012 30, Olorunfemi Street, Igando, Alomosho, Lagos 5. Netbeam Nigeria Limited 1st August, 2007 31 st July, 2012 13, Deco Road, Warri, Delta State 6. Trefoil Networks Limited 1st August, 2007 31 st July, 2012 4, Central School Road, Onitsha, Anambra State 7. Or acle Integrated Services Limited 1st August, 2007 31 st July, 2012 34, Obadeyi Close, Off Awolowo Road, S/W Ikoyi, Lagos 8. Radial Circle Telecommunications Limited 1st August, 2007 31 st July, 2012 56, Balarabe Musa Crescent, Victoria Island, Lagos 9. Gulf Te chnologies Network Limited 1st August, 2007 31 st July, 2012 Suite 18, Zone 3 Shopping Complex, Wuse II, Abuja 10. Entouche Networks (Nig) Ltd 1st August, 2007 31 st July, 2012 2, Temple Ejekwe Close, 1 st Artillery, Port Harcourt/Aba Expressway, Port Harcourt, Rivers State 11. Owa Communications Limited 1st August, 2007 31 st July, 2012 6, Tola Adewumi, Maryland, Lagos 1 12. Alphatess Integrated Services Limited 1st September, 2007 31 st August, 2012 25, Shekoni Street, Coker Village, Iganmu, Lagos 13. Sitech Nigeria Lim ited 1st September, 2007 31 st August, 2012 1, Montgomery Way, Yaba, Lagos 14. -

2007-Annual-Report-Financial-Statements.Pdf

United Bank for Africa Plc 2007 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNUAL 2007 1 Core Values Humility Empathy Integrity Resilience Synonymous with Knowledge of the Every member of the It is part of the culture in meekness and a belief customer and intimate UBA group is taught to UBA to pro-actively that the “Customer is understanding of their uphold the virtues of conceptualise, design and King”. Products and businesses is an integral moral excellence, honesty, develop products and services cover every part of the Group’s wholeness and sincerity services, which surpass segment of the market. marketing strategy, and in all interactions the expectations of At UBA, staff are taught this is done with a view with customers, service customers, no matter the not to despise small to developing mutually providers, fellow staff and odds. The Bank’s innate beginnings. By a beneficial and enduring all other stakeholders. strength also enables deliberate business relationships. We are This value has proven it to adapt to philosophy, numerous constantly driven by a tremendously helpful in fast changing economic start-ups and new strong desire to assist our building the UBA brand. trends and cycles. business initiatives have customers in their efforts been supported from to create value. incubation to maturity. We partner with our customers in a way that reflects understanding and appreciation of their businesses. 01 02 03 04 UBA Annual Report 2007 Group Financial Highlights 4 Corporate Information 7 The Board -

Year 2018 Annual Report

Annual Report FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2018 NDIC ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Our Vision To be the best deposit insurer in the world by 2020 Our Mission To protect depositors and contribute to the stability of the financial system through effective supervision of insured institutions, provision of financial and technical assistance to eligible insured institutions, prompt payment of guaranteed sums and orderly resolution of failed insured financial institutions. Our Core Values Honesty Respect & Fairness Discipline Professionalism Team Work and Passion iii NDIC ANNUAL REPORT 2018 MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE v NDIC ANNUAL REPORT 2018 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE BOARD OF DIRECTORS INTERNAL AUDIT MANAGING DIRECTOR/ CHIEF LEGAL DEPARTMENT/ DEPARTMENT EXECUTIVE OFFICER BOARD SECRETARIAT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR (CORPORATE SERVICES) (OPERATIONS) STRATEGY FINANCE DEPARTMENT DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT INSURANCE & SURVEILLANCE DEPARTMENT HUMAN RESOURCE DEPARTMENT RESEARCH, POLICY & BANK EXAMINATION INTERNATIONAL DEPARTMENT PROCUREMENT & RELATIONS MANAGEMENT SERVICES DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT CLAIMS NDIC ACADEMY ENTERPRISE RISK RESOLUTION MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT ENGINEERING AND TECHNICAL ASSET MANAGEMENT SERVICES DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT COMMUNICATIONS & PUBLIC AFFAIRS PERFORMANCE UNIT MANAGEMENT UNIT SPECIAL INSURED INSTITUTIONS DEPARTMENT ESTABLISHMENT OFFICE, LAGOS INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT vi NDIC ANNUAL REPORT 2018 HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS/UNITS/ZONAL OFFICES Mr. B. D. Umar - Director, Asset Management Mr. M. M. Ibrahim - Director, Bank Examination Mr. M. A. Ahmed - Director, Human Resource Ms. D. O. Okonta - Director, Finance Mr. J. J. Etopidiok - Director, Special Insured Institutions Mr. A. S. Bello - Director, Claims Resolution Mr. F. O. Ekechi - Director, Strategy Development Mr. M. Y. Umar - Director, Insurance & Surveillance Dr. S. A. Oluyemi - Director, Research, Policy & International Relations Mr. B. A. Taribo - Director, Legal & Secretary to the Corporation Mr. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Olufemi Daniel Durodola OFFICE ADDRESS: Covenant University College of Science and Technology Department of Estate Management Km. 10, Idiroko Road, Canaan Land P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State Nigeria. University Tel: +234 – 014542070 Website:www.covenantuniversity.edu.ng Personal Tel: +2348036105028 Personal e-mail: [email protected] ================================================================================= BIO-DATA. Place & Date of Birth: Ibadan, Oyo State Nigeria, 31st January 1956. Home Address: 9, Oluwalobawase Street, Ejigbo, Lagos. Present Postal Address: P.O Box 9877 Shomolu, Lagos. Post Code 100007 Home Town: Odoka‟s Compound, Obagun, Ikirun, Osun State Alternate e-mail Addresses: [email protected] Nationality at Birth: Nigerian. Present Nationality: Nigerian. Marital Status: Married Number and Ages of Children: Four (34, 29, 26, 24) EDUCATION 2009 Ph.D Estate Management, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria 1992 M.Sc. (Construction Management) Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife Nigeria 2002 Masters of Business Administration (M.B.A), University of Ado-Ekiti, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 1 1999 Professional Diploma in Estate Management, College of Estate Management, Reading, England 1981 B.Sc (Hons). (Building Technology) 21 University of Ife, Ile-Ife, Nigeria ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 1/9/2014 – To-Date: Associate Professor of Estate Management, Covenant University, Department of Estate Management 1/9/ 2010 -30/8/2014: Senior Lecturer, Covenant University, Ota, Department of Estate Management -

Nigeria's Public Buildings of Early Statehood: Interpreting Their

International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Research E-ISSN 2545-5303 P-ISSN 2695 2203 Vol. 6 No. 4 2020 www.iiardpub.org Nigeria’s Public Buildings of Early Statehood: Interpreting Their Current Situation and Status Ndubisi Onwuanyi Department of Estate Management, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, University of Benin, PMB 1154, Benin City [email protected] Abstract Public buildings are communal property. Thus, the manner in which they are kept is indicative of the priorities of the owning community, society or state. This means that the recognition or value which society places on such buildings is deducible from their situation. In its first two decades of statehood, Nigeria developed public buildings which, for historical reasons, if nothing else, warrant classification and preservation as monuments. However, public commentary suggests that there has been a pervasive neglect of these buildings, possibly implying a loss of interest and memory on the part of government and citizens. In this paper, the major public buildings of that era are identified and the condition and apparent status of three selected structures are evaluated. The findings are that these buildings have mainly been in neglect and ineffectively managed; second, they are not physically identified as memorial monuments; neither are they remarked nor officially recognised as important state symbols. This leads to the inescapable conclusion that there has been a loss of interest and memory by society, particularly on the part of government. It is recommended that Nigeria recognises and discharges its obligation to manage effectively its common patrimony. Key Words: Nigeria Public buildings; Public monuments; Situation; Status; 1.0 INTRODUCTION Public buildings serve the purposes of governance and the provision of services to the governed.