Evidence from the Paul Manafort Prosecution and the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S3306

S3306 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 11, 2019 perpetuating the opioid epidemic, fuel- RECESS ganda and identify foreign attempts to ing a cycle of violence, and abusing in- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under influence Congress and the American nocent civilians, they are growing rich- the previous order, the Senate stands public. Until recently, however, this er and richer by the minute. in recess until 2:15 p.m. Foreign Agents Registration Act has Targeting these organizations means Thereupon, the Senate, at 12:30 p.m., been seldom used. more than stopping the flow of drugs recessed until 2:15 p.m. and reassem- Now—get this—only 15 violators of into our country; it means ending a bled when called to order by the Pre- this act have been criminally pros- cycle of crime and violence and work- ecuted since 1966, and 1966 was the date siding Officer (Mrs. CAPITO). ing together with Mexico and Central when this law was last updated. Of American countries to help them es- f course, now I am trying to update it cape the savage grip of these criminal EXECUTIVE CALENDAR—Continued again. About half of these prosecu- organizations. tions, of the 15, stem from the work of The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Sen- Additionally, we need to strengthen Special Counsel Mueller’s investiga- ator from Iowa. security cooperation with our inter- tion, though that is not due to the lack national partners so that they are able FOREIGN AGENTS DISCLOSURE AND of foreign influence efforts to affect REGISTRATION ENHANCEMENT ACT to more effectively fight side by side our Federal decision making. -

Corruption in the Defense Sector: Identifying Key Risks to U.S

Corruption in the Defense Sector: Identifying Key Risks to U.S. Counterterrorism Aid Colby Goodman and Christina Arabia October 2018 About Center for International Policy The Center for International Policy promotes cooperation, transparency, and accountability in U.S.global relations. Through research and advocacy, our programs address the most urgent threats to our planet: war, corruption, inequality, and climate change. CIP’s scholars, journal- ists, activists and former government ofcials provide a unique mixture of access to high-level ofcials, issue-area expertise, media savvy and strategic vision. We work to inform the public and decision makers in the United States and in international organizations on policies to make the world more just, peaceful, and sustainable. About Foriegn Influence Transparency Inititative While investigations into Russian infuence in the 2016 election regularly garner front-page head- lines, there is a half-billion-dollar foreign infuence industry working to shape U.S. foreign policy every single day that remains largely unknown to the public. The Foreign Infuence Transparency Initiative is working to change that anonymity through transparency promotion, investigative research, and public education. Acknowledgments This report would not have been possible without the hard work and support of a number of people. First and foremost, Hannah Poteete, who tirelessly coded nearly all of the data mentioned here. Her attention to detail and dedication to the task were extraordinary. The report also could not have been completed without the exemplary work of Avery Beam, Thomas Low, and George Savas who assisted with writing, data analysis, fact-checking, formatting, and editing. Salih Booker and William Hartung of the Center for International Policy consistently supported this project, all the way from idea inception through editing and completion of this report. -

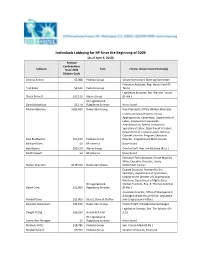

Individuals Lobbying for BP Since the Beginning of 2009

Individuals Lobbying for BP Since the Beginning of 2009 (as of June 4, 2010) Political Contributions Lobbyist Since 2008 Firm Former Government Position(s) Election Cycle Cristina Antelo $5,008 Podesta Group Senate Democratic Steering Committee Executive Assistant, Rep. Harold Ford (D- Teal Baker $9,160 Podesta Group Tenn.) Legislative Assistant, Sen. Blanche Lincoln Chuck Barnett $17,150 Alpine Group (D-Ark.) DC Legislative & David Beaudreau $2,170 Regulatory Services None found Michael Berman $282,650 Duberstein Group Vice President's Office (Walter Mondale) Communications Director, House Appropriations Committee; Department of Labor, Employment Standards Administration; Special Assistant to Secretary of Labor, Department of Labor; Department of Transportation, General Counsel's Honors Program; Executive Paul Brathwaite $51,150 Podesta Group Director, Congressional Black Caucus Michael Brien $0 BP America None found Bob Brooks $90,150 Alpine Group Chief of Staff, Rep. Jim McCrery (R-La.) Matt Caswell $0 BP America None found Executive Floor Assistant, House Majority Whip; Executive Director, House Steven Champlin $179,550 Duberstein Group Democratic Caucus Deputy Executive Assistant to the Secretary, Department of Agriculture; Deputy to the Director of Congressional Relations, Department of Agriculture; DC Legislative & Special Assistant, Rep. E. Thomas Coleman David Crow $15,000 Regulatory Services (R-Mo.) Associate Director, Office of Management & Budget; White House Office, Legislative Randall Davis $22,800 Stuntz, Davis & Staffier and Congressional Affairs Kenneth Duberstein $34,650 Duberstein Group Chief of Staff, President Ronald Reagan Legislative Director, Sen. Tim Johnson (D- Dwight Fettig $16,050 Arnold & Porter S.D.) DC Legislative & Laurie-Ann Flanagan $0 Regulatory Services None found Kimberly Fritts $18,780 Podesta Group Sen. -

FARA Second Semi-Annual Report

U.S. Department of Justice . Washington, D.C. 20530 Report of the Attorney General to the Congress of the United States on the Administration of the . Foreign Agents Registration Act . of 1938, as amended, for the six months ending December 31, 2009 Report of the Attorney General to the Congress of the United States on the Administration of the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, for the six months ending December 31, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................... 1-1 AFGHANISTAN......................................................1 ALBANIA..........................................................2 ALGERIA..........................................................3 ANGOLA...........................................................4 ARGENTINA........................................................5 ARUBA............................................................6 AUSTRALIA........................................................7 AUSTRIA..........................................................9 AZERBAIJAN.......................................................10 BAHAMAS..........................................................12 BAHRAIN..........................................................13 BARBADOS.........................................................14 BELGIUM..........................................................15 BELIZE...........................................................16 BERMUDA..........................................................17 BOLIVIA..........................................................19 -

Before the Federal Election Commission Thomas Giles

BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION THOMAS GILES, STEPHANIE BARNARD ) CAROLE ELIZABETH LEVERS, and ) J. WHITFIELD LARRABEE, ) Complainants ) ) -1 .• V. ) MURNO. I'LIT- • C' -.1 ) -rs • !••• PARTY OF REGIONS, EUROPEAN CENTRE ) '.'i '3 FOR A MODERN UKRAINE, INA KIRSCH, )- •:o VIKTOR YANUKOVCYH, ) :;C-i REPRESENTATIVE DANA T. ROHRABACHER,) s m REPRESENTATIVE EDWARD R. ROYCE, ) § SENATOR JAMES E. RISCH, ) xs COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT ) CONGRESSMAN DANA ROHRABACHER, ) ROYCE CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE, ) JIM RISCH FOR U.S. SENATE COMMITTEE, ) JACK WU, KELLY LAWLER, JEN SLATER, ) R. JOHN DMSINGER, PAUL J. MANAFORT, .JR., ) JOHN V. WEBER, EDWARD S. KUTLER, ) MICHAEL MCSHERRY, DEIRDRE STACH, ) GREGORY M. LANKLER, MERCURY, LLC, ) MERCURY PUBLIC AFFAIRS, LLC d/b/a ) MERCURY/CLARK & WEINSTOCK, ) DMP INTERNATIONAL, LLC, and ) DAVIS, MANAFORT AND FREEDMAN, ) Respondents ) ^ ) COIVIPLAINT 1. This is a complaint based on information and belief that the Respondents violated the Federal Election Campaign Act, as amended by the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. The Respondents participated in a scheme in which foreign nationals, the Party of Regions (of Ukraine) and the European Centre For a Modem Ukraine, indirectly gave campaign contributions to the political committees of Representative Dana Rohrabacher, Representative Edward Royce and Senator James Risch. As a result of this illegal scheme, campaign contributions originating with foreign nationals corrupted the 2014 primary and general elections, the deliberations of the United States Senate and the deliberations of the United States House of Representatives. 2. Representative Dana T. Rohrabacher ("Rohrabacher") Representative Edward R. Royce ("Royce") and Senator James E. Risch ("Risch"), illegally accepted, received and retained campaign contributions that they knew were made by foreign nationals in the names of lobbyists and foreign agents. -

The Vilnius Moment

The Vilnius Moment PONARS Eurasia Policy Perspectives March 2014 The Vilnius Moment PONARS Eurasia POLICY PERSPECTIVES March 2014 The papers in this volume are based on a PONARS Eurasia/IESP policy workshop held in Chisinau, Moldova, December 5-7, 2013. PONARS Eurasia is an international network of academics that advances new policy approaches to research and security in Russia and Eurasia. PONARS Eurasia is based at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES) at the George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs. This publication was made possible by grants from Carnegie Corporation of New York and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. Program Directors: Henry E. Hale and Cory Welt Managing Editor: Alexander Schmemann Program Coordinator: Olga Novikova Visiting Fellow and Russian Editor: Sufian Zhemukhov Research Assistant: Daniel J. Heintz PONARS Eurasia Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES) Elliott School of International Affairs The George Washington University 1957 E Street, NW, Suite 412 Washington, DC 20052 Tel: (202) 994-6340 www.ponarseurasia.org © PONARS Eurasia 2014. All rights reserved Cover image: A Moldovan veteran laughs while listening to newly elected Moldovan President Nicolae Timofti's speech outside the Republican Palace in Chisinau, Moldova, Friday, March 16, 2012. Moldova's Parliament elected Nicolae Timofti, 65, a judge with a European outlook as president, ending nearly three years of political deadlock in the former Soviet republic. (AP Photo/John McConnico) Contents About the Authors iv Foreword vi Cory Welt, Henry E. -

From the Halls of Congress to K Street: Government Experience and Its Value for Lobbying

PAMELA BAN University of California, San Diego MAXWELL PALMER Boston University BENJAMIN SCHNEER Harvard Kennedy School From the Halls of Congress to K Street: Government Experience and its Value for Lobbying Lobbying presents an attractive postcongressional career, with some for- mer congressional members and staffers transitioning to lucrative lobbying ca- reers. Precisely why congressional experience is valued is a matter of ongoing debate. Building on research positing a relationship between political uncertainty and demand for lobbyists, we examine conditions under which lobbyists with past congressional experience prove most valuable. To assess lobbyist earnings, we de- velop a new measure, Lobbyist Value Added, that reflects the marginal contribu- tion of each lobbyist on a contract, and show that previous measures understate the value of high-performing lobbyists. We find that former staffers earn revenues above their peers during times of uncertainty, and former members of Congress generate higher revenue overall, which we identify by comparing revenues gener- ated by individuals who narrowly won election to those who narrowly lost. These findings help characterize when lobbyists with different skillsets prove most valu- able and the value added by government experience. While some politicians remain in office until the end of their professional lives, many others are defeated or choose to leave office to explore the career options available to them outside of electoral politics. Former officials receive job offers and ac- cept positions that reward them for their political background; roughly one in four former high-level politicians and government officials go on to postpolitical employment as a board director or lobbyist (Palmer and Schneer 2019). -

The Trans-Pacific Partnership: This Is What Corporate Governance Look

The Trans-Pacific Partnership: This Is What Corporate Governance Look... http://truth-out.org/news/item/12857-the-trans-pacific-partnership-this-i... Tuesday, 20 November 2012 11:46 By Andrew Gavin Marshall, Occupy.com | News Analysis In 2008, the United States Trade Representative Susan Schwab announced the U.S. entry into the Trans-Pacific Partnership talks as “a pathway to broader Asia-Pacific regional economic integration.” Originating in 2005 as a “Strategic Economic Partnership” between a few select Pacific countries, the TPP has, as of October 2012, expanded to include 11 nations in total: the United States, Canada, Mexico, Peru, Chile, New Zealand, Australia, Brunei, Singapore, Vietnam and Malaysia, with the possibility of several more joining in the future. What makes the TPP unique is not simply the fact that it may be the largest “free trade agreement” ever negotiated, nor even the fact that only two of its roughly 26 articles actually deal with “trade,” but that it is also the most secretive trade negotiations in history, with no public oversight, input, or consultations. Since the Obama administration came to power in January of 2009, the Trans-Pacific Partnership has become a quiet priority for the U.S., which overtook the leadership role in the “trade agreement” talks. In 2010, when Malaysia joined the TPP, the Wall Street Journal suggested that the “free-trade pact” could “serve as a counterweight to China’s economic influence,” with Japan and the Philippines both expressing interest in joining the talks. In the meantime, the Obama administration and other participating nations have been consulting and negotiating not only with each other, but with roughly 600 corporations involved. -

State of New York County of Erie I

STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF ERIE I, Darlene Porter, duly swear that I am employed with The Buffalo News, a newspaper publication based in Buffalo, New York, as the Multimedia Major Account Executive and further swear that the Next Era Energy insertion ran in The Buffalo News on the following date(s): Date(s): January 30, 2019 February 6, 2019 Signature Sworn to before me on this 11th day of February 2019 Notary Signature BARBARA ANNE JUZWtAK Notary Public:, Stata of~ffe;;~ Appeinted In Ntagara My CommlSSion Expires ' The Buffalo News/Wednesday, January 30, 2019 A3 National News Trek across border veers migrants into more remote terrain By Simon Romero expanding it to crossings in Arizona, and Caitlin Dickerson New Mexico and Texas. Taken together, these moves effec- NEW YORK TIMES tively have forced some Central Amer- ANTELOPE WELLS, N.M. – The ican migrants to wait for months to Border Patrol’s tiny base in the south- apply for asylum, sometimes sleeping west corner of New Mexico is so re- on the street or in crowded shelters in mote that the wind howls through the Mexican border cities. surrounding basin where jaguars still Frustrated and increasingly des- stalk their prey. perate, thousands of families have But that hasn’t stopped thousands lately been opting to pay smugglers to of Central Americans from journey- take them to remote border stations ing in recent weeks to the rural out- where they can surrender quickly to post and other isolated points along U.S. officials and hope to be allowed the Southwest border, launching in- to remain in the United States while creasingly desperate bids for asylum their asylum claims are processed. -

Washington Consultants and Opaque Ukrainian Government Tenders

Outside View: Washington consultants and opaque Ukrainian government tenders Published: March. 28, 2013 TARAS KUZIO || UPI Outside View Commentator WASHINGTON, March 28 (UPI) -- WASHINGTON, March 28 (UPI) -- Foreign Agent Registration Act (Department of Justice) reporting shows that authoritarian Ukrainian Presidents Leonid Kuchma and Viktor Yanukovych have poured far more millions of U.S. dollars into Washington political consultants, lobbyists and lawyers than pro-Western opposition and ruling "orange" forces. In addition to the on-going contract with Davis Manafort International since 2005, the Yanukovych administration and Party of Regions, Arnall Golden Gregory LLP and Tauzin Consultants LLC provide consultancy services to Party of Regions parliamentary deputy Petro Shpenov for the sum of $40,000 per month. In 2010, the government of Ukrainian Prime Minister Nikolai Azarov paid $3 million for an international audit of the 2007-10 Tymoshenko government. The contract was given to Trout Cacheris, a law and lobbying firm, Akim Gump Strauss Hauer and Feld, an international law firm whose client list includes Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, and Kroll investigative agency. None of the three companies is professional auditors. Vin Weber was awarded the endowment's Democracy Service Medal in recognition of his service as National Endowment for Democracy chairman (2001-09). Weber, one of U.S. presidential candidate Mitt Romney's top foreign-policy advisers, is a registered lobbyist for the European Centre for a Modern Ukraine. This represents a clear contradiction, Weber, after promoting democracy for the first decade of this century, became a lobbyist for a government that is dismantling the democratic achievements of the Orange Revolution. -

How to Charge Americans in Conspiracies with Russian Spies?

BREAKING! NYT DISCOVERS TWEETS THEY DISCOVERED 3 MONTHS AGO Today, July 26, NYT has a breaking news story that Robert Mueller is investigating Trump’s tweets in a “wide-ranging obstruction inquiry.” The special counsel, Robert S. Mueller III, is scrutinizing tweets and negative statements from the president about Attorney General Jeff Sessions and the former F.B.I. director James B. Comey, according to three people briefed on the matter. Several of the remarks came as Mr. Trump was also privately pressuring the men — both key witnesses in the inquiry — about the investigation, and Mr. Mueller is examining whether the actions add up to attempts to obstruct the investigation by both intimidating witnesses and pressuring senior law enforcement officials to tamp down the inquiry. Mr. Mueller wants to question the president about the tweets. His interest in them is the latest addition to a range of presidential actions he is investigating as a possible obstruction case: private interactions with Mr. Comey, Mr. Sessions and other senior administration officials about the Russia inquiry; misleading White House statements; public attacks; and possible pardon offers to potential witnesses. This breaking news tees up this quote from Rudy Giuliani. Mr. Trump’s lead lawyer in the case, Rudolph W. Giuliani, dismissed Mr. Mueller’s interest in the tweets as part of a desperate quest to sink the president. “If you’re going to obstruct justice, you do it quietly and secretly, not in public,” Mr. Giuliani said. It’s a really interesting breaking news story, because the [squints closely] NYT reported, [squints again] on April 30, that Jay Sekulow had collected this list of questions Mueller wanted to ask the President in March. -

Memory Key Or a Similarly Portable Data- Storage Device

Good morning Mr. Chairman, Mr. Ranking Member, Committee members of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, and staff. My name is Roger J. Stone, Jr., and with me today are my counsel, Grant Smith and Robert Buschel. I am most interested in correcting a number of falsehoods, misstatements, and misimpressions regarding allegations of collusion between Donald Trump, Trump associates, The Trump Campaign and the Russian state. I view this as a political proceeding because a number of members of this Committee have made irresponsible, indisputably, and provably false statements in order to create the impression of collusion with the Russian state 1 Stone Open ng Statement F na without any evidence that would hold up in a US court of law or the court of public opinion. I am no stranger to the slash and burn aspect of American politics today. I recognize that because of my long reputation and experience as a partisan warrior, I am a suitable scapegoat for those who would seek to persuade the public that there were wicked, international transgressions in the 2016 presidential election. I have a long history in this business: I strategize, I proselytize, I consult, I electioneer, I write, I advocate, and I prognosticate. I’m a New York Times bestselling author, I have a syndicated radio show and a weekly column, and I report for Infowars.com at 5 o'clock eastern every day. 2 Stone Open ng Statement F na While some may label me a dirty trickster, the members of this Committee could not point to any tactic that is outside the accepted norms of what political strategists and consultants do today.