Draft Recovery Plan for Jarbidge Population of Bull Trout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12. Owyhee Uplands Section

12. Owyhee Uplands Section Section Description The Owyhee Uplands Section is part of the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion. The Idaho portion, the subject of this review, comprises southwestern Idaho from the lower Payette River valley in the northwest and the Camas Prairie in the northeast, south through the Hagerman Valley and Salmon Falls Creek Drainage (Fig. 12.1, Fig. 12.2). The Owyhee Uplands spans a 1,200 to 2,561 m (4,000 to 8,402 ft) elevation range. This arid region generally receives 18 to 25 cm (7 to 10 in) of annual precipitation at lower elevations. At higher elevations, precipitation falls predominantly during the winter and often as snow. The Owyhee Uplands has the largest human population of any region in Idaho, concentrated in a portion of the section north of the Snake River—the lower Boise and lower Payette River valleys, generally referred to as the Treasure Valley. This area is characterized by urban and suburban development as well as extensive areas devoted to agricultural production of crops for both human and livestock use. Among the conservation issues in the Owyhee Uplands include the ongoing conversion of agricultural lands to urban and suburban development, which limits wildlife habitat values. In addition, the conversion of grazing land used for ranching to development likewise threatens wildlife habitat. Accordingly, the maintenance of opportunity for economically viable Lower Deep Creek, Owyhee Uplands, Idaho © 2011 Will Whelan ranching operations is an important consideration in protecting open space. The aridity of this region requires water management programs, including water storage, delivery, and regulation for agriculture, commercial, and residential uses. -

Julia's Unequivocal Nevada Klampout

Julia's Unequivocal Nevada Klampout #35 JARBIDGE clamper year 6019 Brought to you by Julia C. Bulette chapter 1864, E Clampus Vitus Researched and interpreted by Jeffrey D. Johnson XNGH, Clamphistorian at chapter 1864 Envisioned by Noble Grand Humbug Bob Stransky Dedicated to Young Golddigging Widders and Old Orphans 2014 c.e. Why Why yes, Jarbidge is a ''fer piece'' from any place. This year's junk trip has the unique quirk that it is not in the Great Basin like the rest of our territory. Northern Elko County is drained by the tributaries of the Owyhee, Bruneau and Jarbidge Rivers. They flow in to the Snake River and out to the sea. To the South the range is drained by the North Fork of the Humboldt and in the East, St. Mary's River. Geology The North American Continental plate moves at a rate of one inch a year in a Southwesterly direction. Underneath the plate is a volcanic hotspot or mantle plume. 10 to 12 million years ago the hotspot was just North of the Idaho border. Over that time it has moved, leaving a trail of volcanic debris and ejectamenta from McDermitt Nevada, East. Now the Yellowstone Caldera area is over the plume. During the middle and late Miocene, a sequence of ash flows, enormous lava flows and basalt flows from 40 odd shield volcanoes erupted from the Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera. The eruptive center has mostly been filled in by lava flows and lacustrine and fluvial sediments. Two hundred Rhinos, five different species of horse, three species of cameloids, saber tooth deer and other fauna at Ashfall Fossil Beds 1000 miles downwind to the East in Nebraska, were killed by volcanic ash from the Bruneau Jarbidge Caldera. -

Final Biological Assessment

REVISED BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Effects of the Modified Idaho Roadless Rule on Federally Listed Threatened, Endangered, Candidate, and Proposed Species for Terrestrial Wildlife, Aquatics, and Plants September 12, 2008 FINAL BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Effects of the Modified Idaho Roadless Rule on Federally Listed Threatened, Endangered, Candidate, and Proposed Species for Terrestrial Wildlife, Aquatics, and Plants Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................... 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE FEDERAL ACTION .................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need..................................................................................................................................3 Description of the Project Area...............................................................................................................4 Modified Idaho Roadless Rule................................................................................................................6 Wild Land Recreation (WLR)...............................................................................................................6 Primitive (PRIM) and Special Areas of Historic and Tribal Significance (SAHTS)..............................7 Backcountry/ Restoration (Backcountry) (BCR)................................................................................10 General Forest, Rangeland, -

Jarbidge Mountains (Updated 2014)

Site Description Jarbidge Mountains (updated 2014) Geologic setting: The Jarbidge Mountains are located within the northeastern portion of Elko County, Nevada. The small mountain range is located between the Copper Mountains to the west and the Snake mountains to the east and southeast. Basement rocks of the Jarbidge quadrangle include schist, quartzite, hornfels, and limestones. These are intruded by a Cretaceous quartz monzonite stock. The basement rocks are displaced along pre-Cretaceous faults. Cambrian and Precambrian rocks are thrust over and upon Paleozoic sedimentary rocks. The early Tertiary volcanics and conglomerates are displaced along normal faults represented by the Copper Creek fault, which dips gently east. The Jarbidge Rhyolite (Miocene) and all older formations are displaced along three sets of faults that dip steeply: one set strikes northward, one northeast, and one northwest. These three sets of faults are locally mineralized (Smith, 1976). The oldest exposures are sedimentary deposits such as limestones and shale towards the western portion of the area (Scott, 1910). Geothermal features: Gray Rock Mine: The Great Basin Groundwater Geochemical Database lists a measurement of 26.7°C in an abandoned mineshaft well in the Gray Rock Mine (Sec. 24, T45N, R58E). Robinson Hole Hot Spring / Murphy Hot Spring / Kitties Hot Hole: (Sec. 29, T47N, R59E) The first acknowledged proprietor was Kittie Wilkins, who diverted river water to create the Kittie’s Hot Hole soaking pool (1885). Patrick Murphy developed a small resort on the property in the early 1900’s and renamed it Murphy Hot Spring, followed by Harry Showalter, who added a swimming pool and changing rooms. -

2020 Elko Guide

STAY & PLAY MORE THAN 17,000 SQUARE FEET OF PURE GAMING SATISFACTION AWAITS YOU AT RED LION HOTEL & CASINO. FIND A WIDE VARIETY OF ALL THE HOTTEST SLOTS AND AN EXCITING SELECTION OF TABLE GAMES INCLUDING BLACKJACK, 3CARD POKER, CRAPS, ROULETTE, AND MORE. YOU’LL ENJOY THE FINEST SPORTS BOOK AND THE ONLY LIVE POKER ROOM IN ELKO. GC: 2050 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-8421 | 800-621-1332 RL: 2065 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-2111 | 800-545-0444 HD: 3015 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-8425 | 888-394-8303 wELKOme to Elko, Nevada! hether you call Elko home, are passing through or plan to come and stay a while, we are confident you’ll find something Elko Convention & Wnew and exciting as you #ExploreElko! Visitors Authority 2020 Elko is a vibrant community offering great Board of Directors food; a wide selection of meeting, conference and lodging accommodation options; wonderful events Matt McCarty, Chair throughout the year; art, museums and historical Delmo Andreozzi attractions and an abundance of outdoor recreation Dave Zornes Toni Jewell opportunities. Chip Stone Whether you’re a trail-blazing, peak bagging, galloping adrenaline junkie or an art strolling, line casting, Sunday driving seeker, your adventure starts Follow us on here, the 2020 Visitors Guide, showcasing all the Elko social media! area has to offer. #ExploreElko, @ExploreElko On behalf of the Elko Convention & Visitors Authority and the City of Elko, thank you for being here and we wish you a safe, wonderful visit! Katie Neddenriep Reece Keener Executive Director, Mayor, Elko Convention & City of Elko Visitors Authority 2020 Elko Visitor’s Guide 1 lko is in the northeastern corner of the State of Nevada, situated on the Humboldt River between Reno, Nevada and Salt Lake City, Utah. -

Mountain City, Ruby Mountains, and Jarbidge Combined Travel

Mountain City, Ruby Mountains and Jarbidge Ranger Districts Combined Travel Management Project Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 3. Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences 3.1. Introduction This chapter summarizes the physical, biological, social, and economic environments that are affected by the alternatives and the effects on that environment that would result from implementation of any of the alternatives. This chapter also presents the scientif ic and analyt ical basis for comparison of the alternatives presented in chapter 2. 3.1.1. Analysis Process Most of the data used in the following analysis are from the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest corporate GIS layers. There is a certain amount of error in the location and alignments included in this GIS data. For example, the road layer overlying the stream layer may show more stream crossings than actually exist on the ground because of the different sources from which the different layers were obtained. Some perennial streams may show up on the map as being intermittent. This may also create some inaccuracies as to the exact location and extent of riparian zones. The Forest is constantly working to improve map accuracies and the corporate GIS layers. For the purposes of this analysis, the best data that is available was used. The data in the tables below and in the project record depict with a reasonable amount of accuracy what would be occurring on the ground for each alternative, within the limitations described above. The changes between alternatives remain relative to each other. 3.1.2. Cumulative Effects According to the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) National Environmental Protection Ac t (NEPA) regulations, “cumulative impact” is the impact on the environment which results from the incremental impact of the action when added to other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions regardless of what agency (federal or non-federal) or person undertakes such actions (40 CFR 1508.7). -

USGS Jarbidge River Bull Trout Project

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Distribution and Movement of Bull Trout in the Upper Jarbidge River Watershed, Nevada Open-File Report 2010-1033 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Distribution and Movement of Bull Trout in the Upper Jarbidge River Watershed, Nevada By M. Brady Allen, Patrick J. Connolly, Matthew G. Mesa, Jodi Charrier, and Chris Dixon Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Open-File Report 2010–1033 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Allen, M.B., Connolly, P.J., Mesa, M.G., Charrier, Jodi, and Dixon, Chris, 2010, Distribution and movement of bull trout in the upper Jarbidge River watershed, Nevada: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010-1033, 80 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. -

Lakes, Rivers & Hot Springs

LAKES, RIVERS & HOT SPRINGS Idaho has some of the most impressive water in the nation, and several of the state’s claims to fame are located in Southwest Idaho. Writers covering adventure, family and nature travel will find uncrowded, accessible lakes, rivers and hot springs in Southwest Idaho. RIVERS Multiple sections of the Payette River and Salmon River LAKES & RESERVOIRS are world-famous whitewater destinations. Watch the Southwest Idaho is a water recreation mecca. The area pros during the North Fork Championships or try for has dozens of reservoirs and lakes, including but not yourself with Cascade Raft & Kayak. limited to: Anderson Ranch, Arrowrock, C.J. Strike, Lake The mighty Snake River runs through Southwest Idaho, Cascade, Deadwood, Lucky Peak, Black Canyon and nourishing a massive agriculture and wine region. The river Payette Lake. turns north at the Oregon-Idaho border and runs through These bodies of water are the perfect place to take the Hells Canyon, the deepest river gorge in North America. boat out for the day. Spend an afternoon on Payette Lake Experience the impressive canyon on a whitewater on a McCall Lake Cruise. Go paddleboarding on clean, raft or jet boat tour with Hells Canyon Adventures or glacial water. Fish year-round in Southwest Idaho — Hells Canyon Raft. You’re sure to see wildlife in Hells it’s one of the only places this far inland where you can Canyon, including bald eagles, raptors, coyotes and bears. catch steelhead and salmon. The Owyhee River and Jarbidge River are perhaps two of the most remote, uncharted waters in the nation. -

A Traditional Use Study of the Hagerman

A TRADITIONAL USE STUDY OF THE I HAGERMAN FOSSIL BEDS NATIONAL MONUMENT L.: AND OTHER AREAS IN SOUTHERN IDAHO Submitted to: Columbia Cascade System Support Office National Park Service Seattle, Washington Submitted by: L. Daniel Myers, Ph.D. Epochs· Past .Tracys Landing, Maryland September, 1998 PLEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERViCE CENTER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ii List of Figures and Tables iv Abstract v CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION l OBJECTIVES l FRAMEWORK OF STUDY 2 STUDY AREAS 4 STUDY POPULATIONS 5 DESIGN OF SUCCEEDING CHAPTERS 5 CHAPTER TWO: PROTOCOL AND STRATEGIES. 7 OBJECTIVES 7 CONTACT WITH POTENTIAL CONSULTANTS 7 SCHEDULING AND APPOINTMENTS 8 QUESTIONNAIRE 8 INTERVIEW SPECIFICS 10 CHAPTER THREE: INTERVIEW DETAILS 12 OBJECTIVES 12 SELF, FAMILY, AND ANCESTORS 12 TRIBAL DISTRIBUTIONS AND FOOD-NAMED GROUPS 13 SETTLEMENT AND SUBSISTENCE 13 FOOD RESOURCES . 14 MANUFACTURE GOODS 15 INDIAN DOCTORS, MEDICINE, AND HEALTH 15 STORIES, STORYTELLING, AND SACRED PLACES 15 CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS AND ISSUES 16 CHAPTER FOUR: COMMUNITY SUMMARIES OF THE FIRST TIER STUDY AREAS 17 OBJECTIVES 17 DUCK VALLEY INDIAN RESERVATION 17 FORT HALL INDIAN RESERVATION 22 NORTHWESTERN BAND OF SHOSHONI NATION 23 CHAPTER FIVE: COMMUNITY SUMMARIES OF THE SECOND TIER STUDY AREAS 25 OBJECTIVES 25 DUCK VALLEY INDIAN RESERVATION 25 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Craters of the Moon 25 City of Rocks National Reserve and Bear River Massacre . 25 FORT HALL INDIAN RESERVATION 26 Craters of the Moon 26 City of Rocks . 28 Bear River Massacre ·28 NORTHWESTERN BAND OF SHOSHONI NATION 29 Craters of the Moon 29 City of Rocks . 29 Bear River Massacre 30 CHAPTER SIX: ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 31 OBJECTIVES 31 SUMMARY REVIEW 31 STUDY AREAS REVIEW 3 3 RECOMMENDATIONS 3 5 REFERENCES CITED 38 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 41 APPENDIX A 43 APPENDIX B 48 APPENDIX C 51 iii LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1: Map of Southern Idaho showing Study Areas 3 Figure 2. -

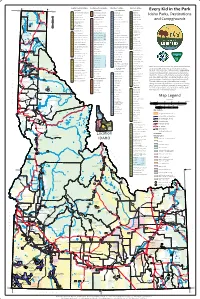

Campgrounds BOUNDARY CO

CANADA o o South-Central Idaho Southwestern Idaho Northern Idaho Eastern Idaho o 117 116 49 o 49 Burley Area Bruneau Area Coeur d’Alene Area Challis Area Every Kid in the Park «¬ Castle Rocks State Park (SP) Bruneau Sand Dunes SP Beauty Bay Bayhorse 1 CS 29 61 BS £ ¤95 Hidden K CR City of Rocks SP 1 Poison Creek Picnic Site 30 Blackwell Island 62 Challis Bridge o Idaho Parks, Destinations Lake o t e n Upper a LW Lake Wolcott SP Greater Boise Area 31 Blue Creek Bay 63 Cottonwood i Priest Lake 119 Lud Drexler Reservoir Bonneville Point 32 Blue Creek Trail 64 Deadman Hole 2 and Campgrounds BOUNDARY CO R 120 McClendon Spring Celebration Park CM Coeur d' Alene Old Mission 65 East Fork i ver 18 Harrison Campground Priest ! Lake £2 Lake Bonners ¤ 3 Clay Peak 33 Crater Lake 66 Garden Creek Milner Historic Ferry 121 PL Recreation Area 19 Cove (CJ Strike Reservoir) 34 Crater Peak 67 Herd Lake Campsite ¤£95 122 Snake River Vista 20 Dedication Point FG Farragut 68 Herd Lake Overlook Twin Falls Area EI Eagle Island SP 35 Gamlin Lake YF Land of the Yankee Fork SP Chase Lake 123 Big Cottonwood 4 8th Street Trail HB Heyburn SP «¬57 69 Jimmy Smith BONNER CO 124 Bruneau Canyon Overlook 5 Lower Hulls Gulch 36 Huckleberry Campground Trailhead Kootenai Joe T. Fallini at ! 125 Bruneau River Launch Site 6 Upper Hulls Gulch 38 Killarney Lake Boat Launch 70 Blue Sandpoint System Trail Mackay Lake ! 126 Bruneau River Take-Out 7 Miller Gulch Ridge to Rivers 39 Killarney Lake Picnic Site Priest ¤£2 71 Little Boulder P 35 end River O 127 Cedar Creek Reservoir 21 -

Evaluation of the Status of Bull Trout in the Jarbidge River Drainage, Idaho

EVALUATION OF THE STATUS OF BULL TROUT IN THE JARBIDGE RIVER DRAINAGE, IDAHO by Charles D. Warren and Fred E. Partridge Idaho Department of Fish and Game Region 4 Jerome, Idaho 83338 IDAHO BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT TECHNICAL BULLETIN NO. 93-1 FEBRUARY 1 9 9 3 EVALUATION OF THE STATUS OF BULL TROUT IN THE JARBIDGE RIVER DRAINAGE, IDAHO Challenge Cost Share Project ID013-435206-25-9Z Charles D. Warren Regional Fishery Biologist and Fred E. Partridge Regional Fishery Manager Idaho Department of Fish and Game 1992 Prepared for the Boise District Bureau of Land Management ABSTRACT In an effort to gather information on bull trout Salvelinus confluentus on the Jarbidge River system within Idaho, habitat and fish communities were assessed at 19 sites on the river and its tributaries. Fish sampling was by either electrofishing or snorkel observations to assess population densities and age structures. Streambed composition, water column habitat, and stream width were evaluated for habitat. Fish sampling resulted in no bull trout, although a self sustaining population of wild redband/rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss spp, whitefish Prosopium williamsoni, four cyprinid, one cottid, and one catastomid species were found. Habitat and water temperature assessments indicate that bull trout may be limited by excessive water temperatures which were intensified by the recent drought conditions. Bull trout were last observed in Idaho by Department personnel in 1991 and one incidental observation was reported during 1992. Research in Nevada sampled bull trout in 1992. 1 INTRODUCTION The only native char in Idaho and Nevada is the bull trout Salvelinus confluentus. -

Geologic Maps of the Grand View-Bruneau Area, Owyhee County, Idaho

Geologic Map of the Grand View-Bruneau Area, Owyhee County, Idaho Margaret D. Jenks Bill Bonnichsen Martha M. Godchaux Idaho Geological Survey Technical Report 98- 1 University of Idaho December 1998 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 Contents Introduction ............................................................... 1 Location ................................................................ 2 General Geologic Setting ........................................................ 2 Structure ................................................................ 5 Hotsprings ............................................................... 6 Acknowledgments ........................................................... 7 References ............................................................... 7 DescriptionofUnits .......................................................... 9 SedimentqUnits .......................................................... 9 Younger Unconsolidated Sediments ............................................... 9 Qal Alluvium (Holocene) .................................................. 9 Qil Intermittent lake sediments (Holocene) ......................................... 9 Qfs Fresh, unvegetated dune sand (Holocene) ....................................... 9 Qaf Alluvial fan deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) ........................ :.............. 9 Qds Vegetated dune sand (Holocene and Pleistocene) ................................... 9 Qls Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) .................................... 9 Qbf Bonneville