Owyhee Monument Proposal Legacy Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julia's Unequivocal Nevada Klampout

Julia's Unequivocal Nevada Klampout #35 JARBIDGE clamper year 6019 Brought to you by Julia C. Bulette chapter 1864, E Clampus Vitus Researched and interpreted by Jeffrey D. Johnson XNGH, Clamphistorian at chapter 1864 Envisioned by Noble Grand Humbug Bob Stransky Dedicated to Young Golddigging Widders and Old Orphans 2014 c.e. Why Why yes, Jarbidge is a ''fer piece'' from any place. This year's junk trip has the unique quirk that it is not in the Great Basin like the rest of our territory. Northern Elko County is drained by the tributaries of the Owyhee, Bruneau and Jarbidge Rivers. They flow in to the Snake River and out to the sea. To the South the range is drained by the North Fork of the Humboldt and in the East, St. Mary's River. Geology The North American Continental plate moves at a rate of one inch a year in a Southwesterly direction. Underneath the plate is a volcanic hotspot or mantle plume. 10 to 12 million years ago the hotspot was just North of the Idaho border. Over that time it has moved, leaving a trail of volcanic debris and ejectamenta from McDermitt Nevada, East. Now the Yellowstone Caldera area is over the plume. During the middle and late Miocene, a sequence of ash flows, enormous lava flows and basalt flows from 40 odd shield volcanoes erupted from the Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera. The eruptive center has mostly been filled in by lava flows and lacustrine and fluvial sediments. Two hundred Rhinos, five different species of horse, three species of cameloids, saber tooth deer and other fauna at Ashfall Fossil Beds 1000 miles downwind to the East in Nebraska, were killed by volcanic ash from the Bruneau Jarbidge Caldera. -

Owyhee River Trip Details

Owyhee River Trip Details BEFORE YOU HEAD OUT □ Plan for the unexpected by purchasing Travel Insurance □ Make lodging arrangements for the night before and night after your trip □ Complete your trip registration and request camping gear on our web site □ Sign your release form on our web site □ Pay the final balance 60 days before the trip THE RENDEZVOUS MEETING PLACE MEETING TIME AFTER THE TRIP Rome Launch Site 9 AM Pacific time on your You’ll return to Rome on Rome, Oregon trip start date the last day around 4 PM Note: Rome, OR is in the Mountain time (MST) zone. We’ll use Pacific time (PST) to stay consistent with the rest of Oregon. There is very little cell phone reception in the area. HOW TO GET THERE Rome is a tiny outpost located on Hwy 95 in the remote southeast corner of the state between Burns Junction and Jordan Valley. We will bring you back to Rome at the end of the trip. If you Fly: The nearest airport is in Boise, ID (115 miles from Rome). There are no afordable shuttle services from the Boise Airport to Rome so if you fly we suggest you rent a car. If you Drive: We meet at the Rome Launch Site in Rome, Oregon. This is a BLM managed campground and launch site and you can leave your car here. Owyhee River Trip Details | Northwest Rafting Company | Page 2 WHERE TO STAY BEFORE AND AFTER Make reservations well in advance. Northwest Rafting Company does not make reservations or cover the cost of your room. -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment Executive Summary

Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment Executive Summary February 2017 A collaborative project of the USRT Foundation and its member Tribes: Burns Paiute Tribe; Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe; Shoshone-Bannock Tribes; Shoshone-Paiute Tribes, Adaptation International, the University of Washington, and Oregon State University. The Upper Snake River Tribes (USRT) Foundation would like to acknowledge and thank the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, for their generous funding contributions to this project. The USRT Foundation would like to acknowledge and thank the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Regions 9 and 10, for providing funding through the Indian General Assistance Program to assist in the completion of this report. A further thank you goes to USRT's EPA project officers Gilbert Pasqua (Region 9) and Jim Zokan (Region 10). The USRT Foundation and the member tribes would also like to express gratitude to Alexis Malcomb, USRT office manager, and Jennifer Martinez, USRT administrator, for their dedicated work behind the scenes to administer this grant effectively, efficiently, and on schedule. Thank you, Alexis and Jennifer! Cover Photo: Upper Snake River at Massacre Rocks. Scott Hauser. 2016 Third Page Photo: The Owyhee River on the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Reservation. Sascha Petersen. 2016 Recommended Citation: Petersen, S., Bell, J., Hauser, S., Morgan, H., Krosby, M., Rudd, D., Sharp, D., Dello, K., and Whitley Binder, L., 2017. Upper Snake River Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation and Member Tribes. Available: http://www.uppersnakerivertribes.org/climate/ ii Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation “What we are seeing on the Owyhee is probably due to less water, but, what else? Hot Days. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Land-Use Plan

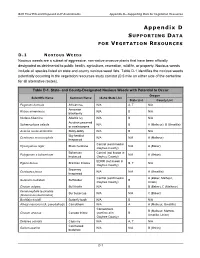

B2H Final EIS and Proposed LUP Amendments Appendix D—Supporting Data for Vegetation Resources Appendix D SUPPORTING DATA FOR VEGETATION RESOURCES D . 1 N O X I O U S W EEDS Noxious weeds are a subset of aggressive, non-native invasive plants that have been officially designated as detrimental to public health, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, or property. Noxious weeds include all species listed on state and county noxious weed lists. Table D-1 identifies the noxious weeds potentially occurring in the vegetation resources study corridor (0.5 mile on either side of the centerline for all alternative routes). Table D-1. State- and County-Designated Noxious Weeds with Potential to Occur Oregon Scientific Name Common Name Idaho State List State List County List Peganum harmala African rue N/A A, T N/A Armenian Rubus armeniacus N/A B N/A blackberry Hedera hibernica Atlantic Ivy N/A B N/A Austrian peaweed Sphaerophysa salsula N/A B A (Malheur), B (Umatilla) or swainsonpea Acaena novae-zelandiae Biddy-biddy N/A B N/A Big-headed Centaurea macrocephala N/A N/A A (Malheur) knapweed Control (confirmed in Hyoscyamus niger Black henbane N/A A (Baker) Owyhee County) Bohemian Control (not known in Polygonum x bohemicum N/A A (Union) knotweed Owyhee County) EDRR (not known in Egeria densa Brazilian Elodea B, T N/A Owyhee County) Brownray Centaurea jacea N/A N/A A (Umatilla) knapweed Control (confirmed in A (Baker, Malheur, Solanum rostratum Buffalobur B Owyhee County) Union) Cirsium vulgare Bull thistle N/A B B (Baker), C (Malheur) Ceratocephala testiculata Bur buttercup N/A N/A C (Baker) (Ranunculus testiculatus) Buddleja davidii Butterfly bush N/A B N/A Alhagi maurorum (A. -

Too Wild to Drill A

TOO WILD TO DRILL A The connection between people and nature runs deep, and the sights, sounds and smells of the great outdoors instantly remind us of how strong that connection is. Whether we’re laughing with our kids at the local fishing hole, hiking or hunting in the backcountry, or taking in the view at a scenic overlook, we all share a sense of wonder about what the natural world has to offer us. Americans around the nation are blessed with incredible wildlands out our back doors. The health of our public lands and wild places is directly tied to the health of our families, communities and economy. Unfortunately, our public lands and clean air and water are under attack. The Trump administration and some in Congress harbor deep ties to fossil fuel and mining interests, and today, resource extraction lobbyists see an unprecedented opportunity to open vast swaths of our public lands. Recent proposals to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling and shrink or eliminate protected lands around the country underscore how serious this threat is. Though some places are appropriate for responsible energy development, the current agenda in Washington, D.C. to aggressively prioritize oil, gas and coal production at the expense of all else threatens to push drilling and mining deeper into our wildest forests, deserts and grasslands. Places where families camp and hike today could soon be covered with mazes of pipelines, drill rigs and heavy machinery, or contaminated with leaks and spills. This report highlights 15 American places that are simply too important, too special, too valuable to be destroyed for short-lived commercial gains. -

Lahontan Cutthroat Trout Species Management Plan for the Upper Humboldt River Drainage Basin

STATE OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE LAHONTAN CUTTHROAT TROUT SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE UPPER HUMBOLDT RIVER DRAINAGE BASIN Prepared by John Elliott SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN December 2004 LAHONTAN CUTTHROAT TROUT SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE UPPER HUMBOLDT RIVER DRAINAGE BASIN SUBMITTED BY: _______________________________________ __________ John Elliott, Supervising Fisheries Biologist Date Nevada Department of Wildlife, Eastern Region APPROVED BY: _______________________________________ __________ Richard L. Haskins II, Fisheries Bureau Chief Date Nevada Department of Wildlife _______________________________________ __________ Kenneth E. Mayer, Director Date Nevada Department of Wildlife REVIEWED BY: _______________________________________ __________ Robert Williams, Field Supervisor Date Nevada Fish and Wildlife Office U.S.D.I. Fish and Wildlife Service _______________________________________ __________ Ron Wenker, State Director Date U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management _______________________________________ __________ Edward C. Monnig, Forest Supervisor Date Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest U.S.D.A. Forest Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……………………………………………………………………..1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………….…2 AGENCY RESPONSIBILITIES……………………………………………………………….…4 CURRENT STATUS……………………………………………………………………………..6 RECOVERY OBJECTIVES……………………………………………………………………19 RECOVERY ACTIONS…………………………………………………………………………21 RECOVERY ACTION PRIORITIES BY SUBBASIN………………………………………….33 IMPLEMENTATION SCHEDULE……………………………………………………………..47 -

Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks

B L M U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks PREPARING OFFICE U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management 3900 E. Idaho St. Elko, NV 89801 Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Prepared by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Elko, NV This page intentionally left blank Decision Record - Memorandum iii Table of Contents _1. Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Decision Record Memorandum ....... 1 _1.1. Proposed Decision .......................................................................................................... 1 _1.2. Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 6 _1.3. Public Involvement ......................................................................................................... 7 _1.4. Rationale ......................................................................................................................... 7 _1.5. Authority ......................................................................................................................... 8 _1.6. Provisions for Protest, Appeal, and Petition for Stay ..................................................... 9 _1.7. Authorized Officer .......................................................................................................... 9 _1.8. Contact Person ............................................................................................................... -

Resolved by the Senate and House Of

906 PUBLIC LAW 90-541-0CT. I, 1968 [82 STAT. Public Law 90-541 October 1, 1968 JOINT RESOLUTION [H.J. Res, 1461] Making continuing appropriations for the fiscal year 1969, and for other purposes. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatimes of tlie United Continuing ap propriations, States of America in Congress assernbled, That clause (c) of section 1969. 102 of the joint resolution of June 29, 1968 (Public Law 90-366), is Ante, p. 475. hereby further amended by striking out "September 30, 1968" and inserting in lieu thereof "October 12, 1968". Approved October 1, 1968. Public Law 90-542 October 2, 1968 AN ACT ------[S. 119] To proYide for a Xational Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and for other purPoses. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Wild and Scenic United States of America in Congress assembled, That (a) this Act Rivers Act. may be cited as the "vVild and Scenic Rivers Act". (b) It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States that certain selected rivers of the Nation which, with their immediate environments, possess outstandin~ly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other similar values, shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit and enjoy ment of l?resent and future generations. The Congress declares that the established national policy of dam and other construction at appro priate sections of the rivers of the United States needs to be com plemented by a policy that would preserve other selected rivers or sections thereof m their free-flowing condition to protect the water quality of such rivers and to fulfill other vital national conservation purposes. -

Wilderness Study Areas

I ___- .-ll..l .“..l..““l.--..- I. _.^.___” _^.__.._._ - ._____.-.-.. ------ FEDERAL LAND M.ANAGEMENT Status and Uses of Wilderness Study Areas I 150156 RESTRICTED--Not to be released outside the General Accounting Wice unless specifically approved by the Office of Congressional Relations. ssBO4’8 RELEASED ---- ---. - (;Ao/li:( ‘I:I)-!L~-l~~lL - United States General Accounting OfTice GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-262989 September 23,1993 The Honorable Bruce F. Vento Chairman, Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands Committee on Natural Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: Concerned about alleged degradation of areas being considered for possible inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System (wilderness study areas), you requested that we provide you with information on the types and effects of activities in these study areas. As agreed with your office, we gathered information on areas managed by two agencies: the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLN) and the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. Specifically, this report provides information on (1) legislative guidance and the agency policies governing wilderness study area management, (2) the various activities and uses occurring in the agencies’ study areas, (3) the ways these activities and uses affect the areas, and (4) agency actions to monitor and restrict these uses and to repair damage resulting from them. Appendixes I and II provide data on the number, acreage, and locations of wilderness study areas managed by BLM and the Forest Service, as well as data on the types of uses occurring in the areas. -

A Traditional Use Study of the Hagerman

A TRADITIONAL USE STUDY OF THE I HAGERMAN FOSSIL BEDS NATIONAL MONUMENT L.: AND OTHER AREAS IN SOUTHERN IDAHO Submitted to: Columbia Cascade System Support Office National Park Service Seattle, Washington Submitted by: L. Daniel Myers, Ph.D. Epochs· Past .Tracys Landing, Maryland September, 1998 PLEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERViCE CENTER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ii List of Figures and Tables iv Abstract v CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION l OBJECTIVES l FRAMEWORK OF STUDY 2 STUDY AREAS 4 STUDY POPULATIONS 5 DESIGN OF SUCCEEDING CHAPTERS 5 CHAPTER TWO: PROTOCOL AND STRATEGIES. 7 OBJECTIVES 7 CONTACT WITH POTENTIAL CONSULTANTS 7 SCHEDULING AND APPOINTMENTS 8 QUESTIONNAIRE 8 INTERVIEW SPECIFICS 10 CHAPTER THREE: INTERVIEW DETAILS 12 OBJECTIVES 12 SELF, FAMILY, AND ANCESTORS 12 TRIBAL DISTRIBUTIONS AND FOOD-NAMED GROUPS 13 SETTLEMENT AND SUBSISTENCE 13 FOOD RESOURCES . 14 MANUFACTURE GOODS 15 INDIAN DOCTORS, MEDICINE, AND HEALTH 15 STORIES, STORYTELLING, AND SACRED PLACES 15 CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS AND ISSUES 16 CHAPTER FOUR: COMMUNITY SUMMARIES OF THE FIRST TIER STUDY AREAS 17 OBJECTIVES 17 DUCK VALLEY INDIAN RESERVATION 17 FORT HALL INDIAN RESERVATION 22 NORTHWESTERN BAND OF SHOSHONI NATION 23 CHAPTER FIVE: COMMUNITY SUMMARIES OF THE SECOND TIER STUDY AREAS 25 OBJECTIVES 25 DUCK VALLEY INDIAN RESERVATION 25 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Craters of the Moon 25 City of Rocks National Reserve and Bear River Massacre . 25 FORT HALL INDIAN RESERVATION 26 Craters of the Moon 26 City of Rocks . 28 Bear River Massacre ·28 NORTHWESTERN BAND OF SHOSHONI NATION 29 Craters of the Moon 29 City of Rocks . 29 Bear River Massacre 30 CHAPTER SIX: ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 31 OBJECTIVES 31 SUMMARY REVIEW 31 STUDY AREAS REVIEW 3 3 RECOMMENDATIONS 3 5 REFERENCES CITED 38 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 41 APPENDIX A 43 APPENDIX B 48 APPENDIX C 51 iii LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1: Map of Southern Idaho showing Study Areas 3 Figure 2. -

Inventory and Assessment of Terrestrial Vegetaion on the 45

Inventory and Assessment of Terrestrial Vegetation on the 45 Ranch Allotment Christopher J. Murphy Steven K. Rust * May 2000 Conservation Data Center Idaho Department of Fish and Game 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Rodney Sando, Director Prepared for: Idaho Field Office, The Nature Conservancy Contract No. IDFO - 052898 - TK * Project leader and principal contact. ii ABSTRACT The Owyhee Plateau region of southwestern Idaho is recognized by many for its ecological significance. In 1996 The Nature Conservancy purchased the 45 Ranch located on the Owyhee Plateau. In 1998 and 1999 an ecological inventory of the conservation site was conducted to prepare a baseline vegetation map of terrestrial plant associations, provide documentation of the composition and structure of major plant associations and condition classes, compile a comprehensive plant species list for the study area, and document the distribution of rare plant species. The report provides an integrated summary of the biological diversity of terrestrial habitats. A vegetation map of the 65,000-acre site was created using Landsat imagery and modeled distribution patterns. The distribution, relative abundance, composition, and structure of 37 plant associations is described. Twelve plant associations were not previously described. The distribution and abundance of 463 common and 19 rare vascular plant species is summarized. Lists of reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and birds observed on the conservation site are provided. The vegetation on 45 Ranch is primarily mid- to late-seral and in good to excellent condition. The ranch encompasses some of the highest quality, representative stands known on the Owyhee Plateau. The effects of resource-based land use practices and chronic disturbances, such as exotic species invasion, and their cumulative effects, however, are apparent.