John Benjamins Publishing Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sogndal Turlag INFORMASJON

2021 INFORMASJON Sogndal Turlag Treng ikkje reise langt for å få flotte GRASROTANDELEN naturopplevingar. Dette biletet er teke utanfor Leikanger. Vil du komme i gang å padle? Sogndal Turlag leiger ut Tilbakebetaling frå Norsk Tipping gjev kvart kajakkar og held introduksjonskurs i år turlaget fleire tusen kroner ekstra i kassen. juni. Det vert vurdert å sette opp fleire kurs dersom etterspurnaden er der. Om du vil støtta laget med 5 % av speleinn- Foto: Toril M. Mulen. satsen din, er det berre å gje beskjed hos Framsidefoto: Me gler oss til å syne fram kommisjonæren eller på www.norsk-tipping.no. det fine turprogrammet for 2021. Her er Sogndal Turlag sitt organisasjonsnummer er turar for alle! Foto: Maria Knagenhjelm 993 746 061 og koden vår til Norsk Tipping er 3277 4886 022 492. 2 LEIAR EIN TRENG IKKJE Å GÅ LANGT FOR Å VERA PÅ TUR Vind i håret, frisk luft i lungene og å kjenne at ein tek i bruk kroppen, gir for mange kjensle av velvære. Den kjem uansett om me har vore utandørs for å nyte naturens ro eller har knytt på oss skoa for å få pulsen opp. Sogndal Turlag vil at alle skal få oppleve turglede og ha lett tilgang til grøne områder i nærmiljøet. Årets satsingsområde frå DNT er nærturar. Derfor passar det godt å utforske Sogndal kommune sitt tilbod, gjerne saman med tur- Foto: Siv Merete Stadheim laget. Gålaget er eit lågterskeltilbod som har mange deltakarar på turane sine. Dei utviklar vaksne og Barnas Turlag både på Leikanger tilbodet i tråd med responsen. og i Sogndal. -

Kulturminnegrunnlag

KULTURMINNEGRUNNLAG for Forvaltningsplan for Byfjellene Sør Smøråsfjellet, Stendafjellet og Fanafjellet Byantikvaren 2006 Byrådsavdeling for Byutvikling Bergen kommune Kulturminnegrunnlag for Byfjellene Sør 2006 FORORD For forvaltningsplan for Byfjellene Sør Smøråsfjellet, Stendafjellet og Fanafjellet Det foreliggende kulturminnegrunnlaget er en del av Byantikvarens arbeid med å kartfeste og sikre informasjon og kunnskap om det historiske kulturlandskapet i Bergen kommune. Kulturminnegrunnlaget er utarbeidet i forbindelse med forvaltningsplan for Byfjellene, og er ment å gi en sammenfatning av kulturminneverdiene i området. Kulturminnegrunnlagene ser generelt på hovedstrukturene i et område, og fokuserer i mindre grad på enkeltobjekter. For de fleste planer og konsekvensutredninger vil de foreligge et tilsvarende kulturminnegrunnlag med lik disposisjon og innholdsrekkefølge. Kulturminnegrunnlagene utarbeidet av Byantikvaren, Byrådsavdeling for Byutvikling, benyttes som underlagsmateriale for videre planarbeid. Det skal også ligge som vedlegg til disse planene frem til politisk behandling, og vil inngå som grunnlagsmateriale for senere saksbehandling innen planområdet. Byantikvaren benytter kulturminnegrunnlagene som underlag for kulturminneplanlegging og saksbehandling knyttet til vern av kulturminner og kulturmiljø. I dette kulturminnegrunnlaget er det i hovedsak fjellområdene som beskrives. Her har det vært en kraftig gjengroing som skyldes at skoggrensen kryper høyere, men også manglende uthogging. Derfor er mange av kulturminnestrukturene ikke lenger synlige og heller ikke registrert. Samtidig er det i fjellområdene relativt få spor etter menneskelig aktivitet, men likevel finnes der noen historiefortellende strukturer. Dette er ulike kulturminnestrukturer og spor etter menneskelig aktivitet som er avsatt i området, og som er med på å beskrive og forstå ulik bruk gjennom tidene. Disse sporene er en kilde til kunnskap og opplevelse, og er dermed med på å gi området en økt bruksverdi. -

Fjaler Kyrkjeblad Desember 2014

2 Kyrkjelydsblad for Fjaler Lyset skin i mørkret Den kjende målaren Rembrandt har laga eit bilete av stallen i mørke er at vi har mist kontakten med skaparen. Den Vonde Betlehem som har gjort eit sterkt inntrykk på meg. Biletet viser har fått oss til å tru at vi lever best når vi er våre eigne herrar, eit svært fattigsleg rom der det ikkje kjem inn lys utanfrå. Lyset utan Gud. Difor vert mørkret avslørt når skaparen sjølv stig som gjer at det er råd å skilja personane på biletet, kjem frå inn i vår verd. barnet som ligg i krubba og lyser. Maria og Josef, hyrdin- gane og dyra i stallen, får alle sitt lys frå barnet. “Han kom til sitt eige, og hans eigne tok ikkje i mot han”. Slik var det den fyrste julenatt. Juleevangeliet seier det slik: “Det var ikkje husrom for dei.” Men det store underet, som vi aldri vert ferdige med å undra oss over og gle oss over, er at han kom likevel. Han let seg ikkje stogga av våre stengde dører. Julenatt ligg han der i krubba og kastar sitt lys over oss, ved at han kjem sjølv inn i vår mørke verd som eit hjelpelaust menneskebarn. Han lyser for oss som frelsaren. Dette lyset opplevde mange sjuke, hjelpelause og utstøytte menneske som seinare møtte Jesus. Og det same lyset strålar frå Golgata, der Jesus andar ut på krossen med orda “Det er fullført” på leppene sine. Fyrst der anar vi den djupaste grunnen til at han kom. Han kom for å ta det store oppgjerd med vårt fråfall som ingen av oss er i stand til å ta. -

Nærskulematrise for Vestland Fylkeskommune

Nærskulematrise for Vestland fylkeskommune Datert 12.10 2020. Vedteke i fylkestinget 30.9.2020, justeringar vedteke i hovudutval for opplæring og kompetanse 3.11.2020 Nærskuleprinsippet Nærskuleprinsippet gjeld inntak til vg1 frå skuleåret 2021/2022. Du høyrer til eit nærskuleområde utifrå kva kommune du er folkeregistrert i. Kva er og korleis får du nærskulepoeng? - Søkjarar utan nærskulepoeng konkurrerer om - Nærskulepoeng er 100 poeng, som blir lagt til ledige plassar når alle søkjarane med nærskulepoeng karakterpoenga frå grunnskulen. er tekne inn. - Du får nærskulepoeng til skulen/-ane i nærskule- Utdanningstilbod som ikkje inngår området ditt. i nærskuleprinsippet Enkelte tilbod i dei vidaregåande skulane er såpass - Søkjarar frå enkelte kommunar/postnummer kan få spesielle at dei ikkje har inntak etter nærskuleområde. Til nærskulepoeng til skular utanfor nærskuleområdet sitt. desse tilboda konkurrerer søkjarane på karakterpoenga frå Det er spesifisert i tabellane på dei neste sidene. grunnskulen. Dette gjeld - yrkes- og studiekompetanse (YSK) - Dersom nærskulen/-ane ikkje har utdannings- - utanlandstilbod programmet du søkjer på, får du nærskulepoeng til alle - International Baccalaureate (IB) skulane som har det tilbodet. Du kan då fritt velje kva - utdanningsprogrammet naturbruk skule du ønskjer å søkje på. - yrkesfaglege løp med studiekompetanse (elektrofag og helse- og oppvekstfag) Søking og inntak - Du kan søkje deg til alle skulane i fylket, men får altså Inntak til vg2 og vg3 berre nærskulepoeng til skulane i nærskuleområdet ditt. - Når du søkjer inntak til vg2 på studieførebuande utdanningsprogram, har du rett til å halde fram på same - Dersom det er fleire søkjarar med nærskulepoeng enn skule som du gjekk vg1. plassar ved eit tilbod, konkurrerer søkjarane på karakter- poeng. -

Kyrkjelydsblad for Arna

Kyrkjelydsblad for Arna NR. 5 • November 2020 • 53. ÅRGANG – Det vakre ikonet som mennesket er, blei formørka i og med syndefallet. Berre Guds fullkomne ikon – Kristus – kan restaurere dette tilsmussa biletet, Guds fullkomne ikon forklarar ikonkunstnar Solrunn Nes. Side 9-11 Med livet på vent Klar for julespelet Ny gudstenesteordning Side 5 Side 2 Side 3 2 KYRKJELYDSBLAD FOR ARNA 4-2020 «Det hende i dei dagar» Emilie og Oda designer kostymer. Tilsette i kyrkja med ansvar for trusopplæring, barne/ungdomsarbeid og arbeid med frivillige har planlagt eit julespel på tvers av generasjonar og arbeidsgreiner. Det overordna målet er å nå alle i Arna med julebodskapen og kjensla av samhald og fellesskap i ei tid prega av isolasjon og einsemd. TEKST OG FOTO: MØYFRID OPHEIM Arna kyrkjelyd har hatt Møtestader som eitt av satsings- områda sine. Mange har arbeidd for å lage gode arrangement der menneske kan møtast på tvers av generasjonar, og der alle kan bidra ut frå eigne føresetnader. Døme på dette er grau tlaurdag kombinert med tiltak for trusopplæring, Open kyrkjestove, Julesalmekveld med Kyrkjekoret og Klubben, og Julefest for alle. Det er vanskeleg å planlegge for advent og jul slik situasjonen er no. Vi opplever at mange menneske saknar å møtast, det gjeld både einslege, eldre og barnefamiliar. Sjølve spelet skal gå føre seg på parkeringsplassen ved kyrkja. Då er vi ute, og det er mogleg for fleire å vere samla på en trygg måte. Rollene i julespelet vert fordelt på søndagsskuleborn, med- lemar i ungdomsklubben, medlemar i Klubben for funksjons- hemma og andre som ønskjer å delta. -

Rehabilitering Utenfor Institusjon Innsatsteam

Hvordan ta kontakt: Du kan selv ta kontakt med oss, eller du kan be helsepersonell l (institusjon, fastlegen, ergo- f Tjenesten tilbys dagtid mandag til fysioterapitjenesten, hjemmesy- Rehabilitering t kepleien) å henvise til oss. Tje- fredag. Det er ingen egenandel på nesten er organisert under Ergo- utenfor tjenesten Rehabilitering utenfor in- og Fysioterapitjenestene i Ber- institusjon gen Kommune: stitusjon i henhold til lov om kom- munale helse og omsorgstjeneste. Arna / Åsane (base Åstveit): 53 03 51 50 / 40 90 64 57 Bergenhus /Årstad (base Engen): Den som søker helsehjelp kan på- 55 56 93 66 / 94 50 38 14 Innsatsteam - klage avgjørelsen dersom det gis av- Fana / Ytrebygda (base Nesttun): slag eller dersom det menes at rettig- 55 56 18 70 / 94 50 79 60 rehabilitering hetene ikke er oppfylt. Klage sendes Fyllingsdalen/ Laksevåg (base Fyllingsdalen): 53 03 30 09 / 94 50 38 15 til Helsetilsynet i fylket og klagen skal være skriftlig (jfr. Lov om pasi- E-post: entrettigheter § 7-2). innsatsteam-rehabilitering@ bergen.kommune.no Rehabilitering utenfor institusjon Oppfølgingsperioden er tverrfaglig og Et ønske om endring innen funksjon, Innsatsteam-rehabilitering gir tjenes- aktivitet og/ eller deltakelse kan være ter til deg som nylig eller innen siste individuelt tilpasset og kan inneholde: utgangspunkt for rehabilitering. år, har fått påvist et hjerneslag eller Kartlegging av funksjon en lett/moderat traumatisk hodeska- Dine mål står sentralt i rehabilite- de. Målrettet trening ringsforløpet. Innsatsteam-rehabilitering er et tverr- Veiledning til egentrening og aktivitet faglig team bestående av fysiotera- peut, ergoterapeut og sykepleier. Samtale, mestring og motivasjon Egentrening og egeninnsats er viktig Oppfølgingen fra Innsatsteam– reha- for å få en god rehabiliteringsprosess. -

Odda 2-Dagars 2017 Resultat 3-Kamp

Odda 2-dagars 2017 Resultat 3-kamp Plass Namn Klubb Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid B-Open Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Ylva Svanberg Helle TIF Viking 02:42 03:20 02:49 08:51 2 Bjørg Kocbach Bergens TF 03:12 04:39 03:45 11:36 3 Kjetil Hjelle Fitjar IL 03:01 03:50 05:16 12:07 4 Trude Kyrkjebø TIF Viking 03:42 04:17 04:23 12:22 5 Kari Secher Bergens TF 04:17 05:54 04:47 14:58 6 Torild Myrli TIF Viking 07:35 05:19 04:16 17:10 C-Open Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Lisa Bakkejord IL Gular 01:57 02:22 02:26 06:45 2 Mette Fitjar Fitjar IL 02:02 03:00 03:38 08:40 3 Olve Hekland IL Gular 02:53 06:21 04:06 13:20 4 Ingrid Roll Fana IL 04:38 07:35 05:25 17:38 D11-12 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Idun Hekland IL Gular 02:23 04:45 04:01 11:09 2 Karina Solheim Øyre Odda OL 05:00 05:02 02:44 12:46 D13-14 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Marie Roll-Tørnquist Fana IL 02:11 02:50 03:33 08:34 2 Kristine Bog Vikane Fana IL 03:06 03:30 03:52 10:28 3 Oda Kjellevold Malde IL Gular 02:49 05:17 03:22 11:28 4 Guro Femsteinevik Varegg Fleridrett 02:29 03:08 06:09 11:46 D15-16 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Mari Fjellbirkeland Johannesen IL Gular 02:18 03:03 03:24 08:45 2 Tora Aasheim Nymark TIF Viking 05:09 03:20 03:36 12:05 3 Ida Solheim Eide Odda OL 03:35 04:32 04:36 12:43 4 Tiril Olausen Haugesund IL 06:25 05:04 05:47 17:16 D17 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Anne Kari Vikingstad Torvastad IL 02:18 02:43 02:47 07:48 2 Ingvild Paulsen Vie Haugesund IL 02:09 02:39 03:02 07:50 3 Kristina Voll Haugesund IL 02:12 02:47 02:53 07:52 4 Tonje -

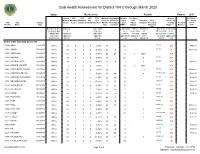

District 104 C.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 104 C through March 2020 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs more than two years old 19560 ARNA 11/13/1970 Active 10 0 0 0 0.00% 10 14 MC,SC N/R $400.65 19562 ASKØY 03/08/1967 Active 37 0 2 -2 -5.13% 38 7 4 MC,SC 24+ $1531.86 31071 AUSTEVOLL 07/01/1975 Active 51 1 3 -2 -3.77% 52 27 0 1 None N/R 19565 BERGEN 05/23/1951 Active 15 0 0 0 0.00% 15 16 7 MC,SC N/R 19561 BERGEN ÅSANE 07/01/1966 Active 24 1 2 -1 -4.00% 26 4 2 2 MC,SC N/R $328.86 88725 BERGEN STUDENT 06/23/2005 Active 2 0 0 0 0.00% 2 20 3 None N/R 19566 BERGEN/BERGENHUS 09/14/1966 Active 25 0 0 0 0.00% 26 9 13 MC,SC N/R $5683.62 31166 BERGEN/BJØRGVIN 09/10/1975 Active 18 0 1 -1 -5.26% 19 44 0 4 M,VP,MC,SC N/R $121.80 28228 BERGEN/LØVSTAKKEN 03/22/1974 Active 21 0 1 -1 -4.55% 22 30 5 MC,SC N/R $164.43 19567 BERGEN/ULRIKEN -

Idyllisk Og Sentralt Mellom Fjord Og Fjell ...På Dørstokken Til Vestlandets

hovedstad ...på dørstokken til Vestlandets til Vestlandets ...på dørstokken og fjell mellom fjord mellom fjord Idyllisk og sentralt Idyllisk og sentralt A RN A U RB A N I DYLL I SK OG SENTR A LT MELLOM FJORD OG FJELL Arna Urban Eksteriøret A RNA U R B AN 3 Boligene har nydelig utsikt mot Arnavågen, "Boligene har nydelig • Vestvendte boliger med gode solforhold over Øyrane sentrum og inn i dalen. Plassert utsikt mot Arnavågen • Mange av leilighetene har utsikt mot over Øyrane sentrum like ved bydelssenteret i Arna bydel finner du Arnavågen et bredt handels- og servicetilbud og kort vei og inn i dalen" • 85 stk. 2, 3, 4 og 5-romsleiligheter til skoler og barnehager. Sist, men ikke minst: fra 40 til 146 m2 Storelva - Bergens beste lakseelv. • Mulighet for parkeringsplass i garasje Borettslaget Arna Urban består av 85 leilighe- • To minutters gange til Arna Stasjon ter, fordelt på to bygninger vendt mot vest og • Reisetid til Bergen sentrum ca. 10 min. B ÅDE ARNA B U nordvest. Leilighetenes areal varierer fra 40 m2 til 146 m2, fra to til fem rom. Med eget garasje- OG B ERGENSER anlegg og de fleste boligene med innglassede terrasser, er Arna Urban et utmerket valg for Arna Urban er perfekt for deg som vil bo deg som ønsker et rolig, idyllisk og sentralt bomiljø med god standard. både landlig og sentralt. Her har du kort vei til Bergen sentrum, Øyrane Torg finnes like utenfor døren. Fjord og fjell ligger for dine føtter. Arna Urban Eksteriøret A RNA U R B AN 5 E N NY BY Arna Urban skal bidra til å urbanisere området rundt jernbanestasjonen i Arna. -

Planomtale Med Konsekvensutgreiing

Planomtale med konsekvensutgreiing E16 og Vossebanen, Arna - Stanghelle E16 og Vossebanen Side: 3 av 250 E16 og Vossebanen, Arna - Dok.nr: UAS-01-A-00011 Planomtale med konsekvensutgreiing Stanghelle Rev: 06B Dato: 13.11.2020 Forord Samferdselsdepartementet har i sitt brev av 8. desember 2015 bede Statens vegvesen og Bane NOR om å utarbeide ein statleg reguleringsplan på strekninga Arna - Stanghelle i tråd med tilrådd konsept «K5» frå konseptvalutgreiinga for E16 og Vossebanen. Departementet har gitt premissar for planarbeidet. Vossebanen og E16 skal gjennomførast som eit felles prosjekt med ein felles reguleringsplan. Statens vegvesen er prosjekteigar på vegne av Bane NOR og Statens vegvesen. Planprosessen skal gjennomførast som statleg reguleringsplan. Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet skal som statleg planmynde vedta planen. Planen fell inn under plan- og bygningslova sine føresegner om konsekvensutgreiing. I statleg plan er dei aktuelle kommunane høyringspart og ikkje planmynde. Det har derfor vore viktig for tiltakshavar å ha god kontakt med både Bergen kommune og Vaksdal kommune i planarbeidet. Prosjektutløysande behov er trygg og påliteleg transport, redusert reisetid, og auka kapasitet for gods på bane. Betre trafikksikkerheit er eit svært avgjerande behov for E16. Reguleringsplanarbeidet har vore organisert som eit fellesprosjekt mellom Statens vegvesen og Bane NOR – med Statens vegvesen som prosjekteigar, og ein felles prosjektorganisasjon. Rambøll-Sweco har vore rådgjevar i planarbeidet. Planprogrammet vart endeleg godkjend 09.11.2020. Planforslaget inneheld ein planomtale og dei juridiske bindande plandokumenta plankart med føresegner. I tillegg er det utarbeidd ei rekke underliggande rapportar og teikningar, som i meir detaljert grad skildrar løysingane som er valt. Desse dokumenta er og viktig for å forstå endeleg utforming av reguleringsplanen. -

Con!Nui" of Norwegian Tradi!On in #E Pacific Nor#West

Con!nui" of Norwegian Tradi!on in #e Pacific Nor#west Henning K. Sehmsdorf Copyright 2020 S&S Homestead Press Printed by Applied Digital Imaging Inc, Bellingham, WA Cover: 1925 U.S. postage stamp celebrating the centennial of the 54 ft (39 ton) sloop “Restauration” arriving in New York City, carrying 52 mostly Norwegian Quakers from Stavanger, Norway to the New World. Table of Con%nts Preface: 1-41 Immigra!on, Assimila!on & Adapta!on: 5-10 S&ried Tradi!on: 11-281 1 Belief & Story 11- 16 / Ethnic Jokes, Personal Narratives & Sayings 16-21 / Fishing at Røst 21-23 / Chronicats, Memorats & Fabulats 23-28 Ma%rial Culture: 28-96 Dancing 24-37 / Hardanger Fiddle 37-39 / Choral Singing 39-42 / Husflid: Weaving, Knitting, Needlework 42-51 / Bunad 52-611 / Jewelry 62-7111 / Boat Building 71-781 / Food Ways 78-97 Con!nui": 97-10211 Informants: 103-10811 In%rview Ques!onnaire: 109-111111 End No%s: 112-1241111 Preface For the more than three decades I taught Scandinavian studies at the University of Washington in Seattle, I witnessed a lively Norwegian American community celebrating its ethnic heritage, though no more than approximately 1.5% of self-declared Norwegian Americans, a mere fraction of the approximately 280,000 Americans of Norwegian descent living in Washington State today, claim membership in ethnic organizations such as the Sons of Norway. At musical events and dances at Leikarringen and folk dance summer camps; salmon dinners and traditional Christmas celebrations at Leif Ericsson Lodge; cross-country skiing at Trollhaugen near Stampede -

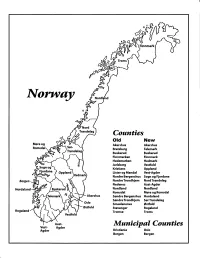

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \.