Coleman Hawkins, the Hawk Flies (1974)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historic Recordings of the Song Desafinado: Bossa Nova Development and Change in the International Scene1

The historic recordings of the song Desafinado: Bossa Nova development and change in the international scene1 Liliana Harb Bollos Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil [email protected] Fernando A. de A. Corrêa Faculdade Santa Marcelina, Brasil [email protected] Carlos Henrique Costa Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil [email protected] 1. Introduction Considered the “turning point” (Medaglia, 1960, p. 79) in modern popular Brazi- lian music due to the representativeness and importance it reached in the Brazi- lian music scene in the subsequent years, João Gilberto’s LP, Chega de saudade (1959, Odeon, 3073), was released in 1959 and after only a short time received critical and public acclaim. The musicologist Brasil Rocha Brito published an im- portant study on Bossa Nova in 1960 affirming that “never before had a happe- ning in the scope of our popular music scene brought about such an incitement of controversy and polemic” (Brito, 1993, p. 17). Before the Chega de Saudade recording, however, in February of 1958, João Gilberto participated on the LP Can- ção do Amor Demais (Festa, FT 1801), featuring the singer Elizete Cardoso. The recording was considered a sort of presentation recording for Bossa Nova (Bollos, 2010), featuring pieces by Vinicius de Moraes and Antônio Carlos Jobim, including arrangements by Jobim. On the recording, João Gilberto interpreted two tracks on guitar: “Chega de Saudade” (Jobim/Moraes) and “Outra vez” (Jobim). The groove that would symbolize Bossa Nova was recorded for the first time on this LP with ¹ The first version of this article was published in the Anais do V Simpósio Internacional de Musicologia (Bollos, 2015), in which two versions of “Desafinado” were discussed. -

Prohibido Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications Presents the jeffrey sultanof master edition prohibido As recorded by benny carter Arranged by benny carter edited by jeffrey sultanof full score from the original manuscript jlp-8230 Music by Benny Carter © 1967 (Renewed 1995) BEE CEE MUSIC CO. All Rights Reserved Including Public Performance for Profit Used by Permission Layout, Design, and Logos © 2010 HERO ENTERPRISES INC. DBA JAZZ LINES PUBLICATIONS AND EJAZZLINES.COM This Arrangement has been Published with the Authorization of the Estate of Benny Carter. Jazz Lines Publications PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA benny carter series prohibido At long last, Benny Carter’s arrangements for saxophone ensembles are now available, authorized by Hilma Carter and the Benny Carter Estate. Carter himself is one of the legendary soloists and composer/arrangers in the history of American music. Born in 1905, he studied piano with his mother, but wanted to play the trumpet. Saving up to buy one, he realized it was a harder instrument that he’d imagined, so he exchanged it for a C-melody saxophone. By the age of fifteen, he was already playing professionally. Carter was already a veteran of such bands as Earl Hines and Charlie Johnson by his twenties. He became chief arranger of the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra when Don Redman left, and brought an entirely new style to the orchestra which was widely imitated by other arrangers and bands. In 1931, he became the musical director of McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, one of the top bands of the era, and once again picked up the trumpet. -

Jazzpress 0612

CZERWIEC 2012 Gazeta internetowa poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej ISSN 2084-3143 KONCERTY Medeski, Martin & Wood 48. Jazz nad Odrą i 17. Muzeum Jazz Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia Mojito w Duc de Lombards z Giladem Hekselmanem Śląski Festiwal Jazzowy Marcus Miller Jarosław Śmietana Trio na Mokotów Jazz Fest Bruce Springsteen And The E Street Band Joscho Stephan W maju Szczecin zakwitł jazzem Mazurki Artura Dutkiewicza na żywo KONKURSY Artur Dutkiewicz, fot. Krzysztof Wierzbowski i Bogdan Augustyniak SPIS TREŚCI 3 – Od Redakcji 68 – Publicystyka 4 – KONKURSY 68 Monolog ludzkich rzeczy 6 – Wydarzenia 72 – Wywiady 72 Jarosław Bothur i Arek Skolik: 8 – Płyty Wszystko ma swoje korzenie 8 RadioJAZZ.FM poleca 77 Aga Zaryan: 10 Nowości płytowe Tekst musi być o czymś 14 Recenzje 84 Nasi ludzie z Kopenhagi i Odense: Imagination Quartet Tomek Dąbrowski, Marek Kądziela, – Imagination Quartet Tomasz Licak Poetry – Johannes Mossinger Black Radio – Robert Glasper Experiment 88 – BLUESOWY ZAUŁEK Jazz w Polsce – wolność 88 – Magia juke jointów rozimprowizowana? 90 – Sean Carney w Warszawie 21 – Przewodnik koncertowy 92 – Kanon Jazzu 21 RadioJAZZ.FM i JazzPRESS polecają y Dexter Calling – Dexter Gordon 22 Letnia Jazzowa Europa Our Thing – Joe Henderson 23 Mazurki Artura Dutkiewicza na żywo The Most Important Jazz Album 26 MM&W – niegasnąca muzyczna marka Of 1964/1965 – Chet Baker 28 48. Jazz nad Odrą i 17. Muzeum Jazz Zawsze jest czas pożegnań 40 Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia i rzecz o bansuri 100 – Sesje jazzowe 43 Mojito w Duc de Lombards 108 – Co w RadioJAZZ.FM -

Powell, His Trombone Student Bradley Cooper, Weeks

Interview with Benny Powell By Todd Bryant Weeks Present: Powell, his trombone student Bradley Cooper, Weeks TBW: Today is August the 6th, 2009, believe it or not, and I’m interviewing Mr. Benny Powell. We’re at his apartment in Manhattan, on 55th Street on the West Side of Manhattan. I feel honored to be here. Thanks very much for inviting me into your home. BP: Thank you. TBW: How long have you been here, in this location? BP: Over forty years. Or more, actually. This is such a nice location. I’ve lived in other places—I was in California for about ten years, but I’ve always kept this place because it’s so centrally located. Of course, when I was doing Broadway, it was great, because I can practically stumble from my house to Broadway, and a lot of times it came in handy when there were snow storms and things, when other musicians had to come in from Long Island or New Jersey, and I could be on call. It really worked very well for me in those days. TBW: You played Broadway for many years, is that right? BP: Yeah. TBW: Starting when? BP: I left Count Basie in 1963, and I started doing Broadway about 1964. TBW: At that time Broadway was not, nor is it now, particularly integrated. I think you and Joe Wilder were among the first to integrate Broadway. BP: It’s funny how it’s turned around. When I began in the early 1960s, there were very few black musicians on Broadway, then in about 1970, when I went to California, it was beginning to get more integrated. -

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ______

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ____________________________________________________ n 1955 Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock was the first rock and roll record to become number one on the hit parade. It had made a stunning introduction in I the opening moments to a film called Blackboard Jungle. But at that time my favourite record was one by Lionel Hampton. I was not alone. Me and my three jazz loving friends couldn’t be bothered spending hard-earned cash on rock and roll records. Our quartet consisted of clarinet, drums, bass and vocal. Robert (nickname Orgy) was learning clarinet; Malcolm (Slim) was going to learn drums (which in due course he did under the guidance of Gordon LeCornu, a percussionist and drummer in the days when Sydney still had a thriving show scene); Dave (Bebop) loved the bass; and I was the vocalist a la Joe (Bebop) Lane. We were four of 120 RAAF apprentices undergoing three years boarding school training at Wagga Wagga RAAF Base from 1955-1957. Of course, we never performed together but we dreamt of doing so and luckily, dreaming was not contrary to RAAF regulations. Wearing an official RAAF beret in the style of Thelonious Monk or Dizzy Gillespie, however, was. Thelonious Monk wearing his beret the way Dave (Bebop) wore his… PHOTO CREDIT WILLIAM P GOTTLIEB _________________________________________________________ *Ian Muldoon has been a jazz enthusiast since, as a child, he heard his aunt play Fats Waller and Duke Ellington on the household piano. At around ten years of age he was given a windup record player and a modest supply of steel needles, on which he played his record collection, consisting of two 78s, one featuring Dizzy Gillespie and the other Fats Waller. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Saxophone Colossus”—Sonny Rollins (1956) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Hugh Wyatt (Guest Essay)*

“Saxophone Colossus”—Sonny Rollins (1956) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Hugh Wyatt (guest essay)* Album cover Original album Rollins, c. 1956 The moniker “Saxophone Colossus” aptly describes the magnitude of the man and his music. Walter Theodore Rollins is better known worldwide as the jazz giant Sonny Rollins, but in addition to Saxophone Colossus, he has also been given other nicknames, most notably “Newk” because of his resemblance to baseball legend Don Newcombe. To use a cliché, Saxophone Colossus best describes Sonny because he is bigger than life. He is an African American of mammoth importance not only because he is the last major remaining jazz trailblazer, but also because he helped to inspire millions of fans and others to explore the religions and cultures of the East. A former heroin addict, the tenor saxophone icon proved that it was possible to kick the drug habit at a time in the 1950s when thousands of fellow musicians abused heroin and other narcotics. His success is testimony to his strength of character and powerful spirituality, the latter of which helped him overcome what musicians called “the stick” (heroin). Sonny may be the most popular jazz pioneer who is still alive after nearly seven decades of playing bebop, hard bop, and other styles of jazz with the likes of other stalwart trailblazers such as Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Clifford Brown, Max Roach, and Miles Davis. He follows a tradition begun by Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker. Eight months after overcoming his habit at a drug rehabilitation facility called “the farm” in Lexington, Kentucky, Sonny made what the jazz cognoscenti rightly contend is his greatest recording ever—ironically entitled “Saxophone Colossus”—which was recorded on June 22, 1956. -

Disco Gu”Rin Internet

ISCOGRAPHIE de ROGER GUÉRIN D Par Michel Laplace et Guy Reynard ● 45 tours ● 78 tours ● LP ❚■● CD ■●● Cassette AP Autre prise Janvier 1949, Paris 3. Flèche d’Or ● ou 78 Voix de son Maitre 5 février 1954, Paris Claude Bolling (p), Rex Stewart (tp), 4. Troublant Boléro FFLP1031 Jacques Diéval et son orchestre et sex- 5. Nuits de St-Germain-des-Prés ● ou 78 Voix de son Maitre Gérard Bayol (tp), Roger Guérin (cnt), ● tette : Roger Guérin (tp), Christian Benny Vasseur (tb), Roland Evans (cl, Score/Musidisc SCO 9017 FFLP10222-3 Bellest (tp), Fred Gérard (tp), Fernard as), George Kennedy (as), Armand MU/209 ● ou 78 Voix de son Maitre Verstraete (tp), Christian Kellens (tb), FFLP10154 Conrad (ts, bs), Robert Escuras (g), Début 1953, Paris, Alhambra « Jazz André Paquinet (tb), Benny Vasseur Guy de Fatto (b), Robert Péguet (dm) Parade » (tb), Charles Verstraete (tb), Maurice 8 mai 1953, Paris 1. Without a Song Sidney Bechet avec Tony Proteau et son Meunier (cl, ts), Jean-Claude Fats Sadi’s Combo : Fats Sadi (vib), 2. Morning Glory Orchestre : Roger Guérin (tp1), Forhenbach (ts), André Ross (ts), Geo ● Roger Guérin (tp), Nat Peck (tb), Jean Pacific (F) 2285 Bernard Hulin (tp), Jean Liesse (tp), Daly (vib), Emmanuel Soudieux (b), Aldegon (bcl), Bobby Jaspar (ts), Fernand Verstraete (tp), Nat Peck (tb), Pierre Lemarchand (dm), Jean Paris, 1949 Maurice Vander (p), Jean-Marie Guy Paquinet (tb), André Paquinet Bouchéty (arr) Claude Bolling (p), Gérard Bayol (tp), (tb), Sidney Bechet (ss) Jacques Ary Ingrand (b), Jean-Louis Viale (dm), 1. April in Paris Roger Guérin (cnt), Benny Vasseur (as), Robert Guinet (as), Daniel Francy Boland (arr) 2. -

The Norton Jazz Recordings 2 Compact Discs for Use with Jazz: Essential Listening 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE NORTON JAZZ RECORDINGS 2 COMPACT DISCS FOR USE WITH JAZZ: ESSENTIAL LISTENING 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott DeVeaux | 9780393118438 | | | | | The Norton Jazz Recordings 2 Compact Discs for Use with Jazz: Essential Listening 1st edition PDF Book A Short History of Jazz. Ships fast. Claude Debussy did have some influence on jazz, for example, on Bix Beiderbecke's piano playing. Miles Davis: E. Retrieved 14 January No recordings by him exist. Subgenres Avant-garde jazz bebop big band chamber jazz cool jazz free jazz gypsy jazz hard bop Latin jazz mainstream jazz modal jazz M-Base neo-bop post-bop progressive jazz soul jazz swing third stream traditional jazz. Special Attributes see all. Like New. Archived from the original on In the mids the white New Orleans composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk adapted slave rhythms and melodies from Cuba and other Caribbean islands into piano salon music. Traditional and Modern Jazz in the s". See also: s in jazz , s in jazz , s in jazz , and s in jazz. Charlie Parker's Re-Boppers. Hoagy Carmichael. Speedy service!. Visions of Jazz: The First Century. Although most often performed in a concert setting rather than church worship setting, this form has many examples. Drumming shifted to a more elusive and explosive style, in which the ride cymbal was used to keep time while the snare and bass drum were used for accents. Season 1. Seller Inventory While for an outside observer, the harmonic innovations in bebop would appear to be inspired by experiences in Western "serious" music, from Claude Debussy to Arnold Schoenberg , such a scheme cannot be sustained by the evidence from a cognitive approach. -

Metaphorical Thoughts on the Birth of Bebop. by Renzo Carli* We Are in the Early Forties of Last Century. Let's Go Together To

Metaphorical thoughts on the birth of bebop. by Renzo Carli* An environment. We are in the early forties of last century. Let’s go together to a nightclub on New York’s West 118th street, in the middle of Harlem: Minton’s Playhouse, housed in a room of the Hotel Cecil. The club takes its name from the owner, Henry Minton, an ex-saxophonist. In 1940, Minton handed over the running to Teddy Hill, a musician who had led a few orchestras in the past and was well liked by black jazzmen. Hill had a brilliant idea to make the place popular: have a small in-house group (Clarke on drums, Monk, as yet unknown, on the piano, Fenton on bass and Guy on trumpet); any of the numerous habitués who wanted to, could bring their instrument with them and play. It is a Monday night and already in the room, filled with cigarette smoke, a strange music can be heard, different from traditional jazz. We go inside: there are a few musicians, all black, involved in a very lively jam session; they are surrounded by a dense crowd of attentive listeners, all strictly black and mostly jazz players. There is a lot of smoke in the room; the musicians are playing in what seems a discordant way, with a very rapid succession of notes and chords that sound sharp but at the same time enthralling. We are at Minton’s on a Monday night, and we are there deliberately; it is the night off for the big New York swing orchestras that play dance music for the whites, and they can have a drink at Minton’s, listen to some extraordinary jam sessions, but also emerge from their passivity and throw themselves into the fray, improvising solos, developing the themes offered with daring new variations. -

Jazzpress 0213

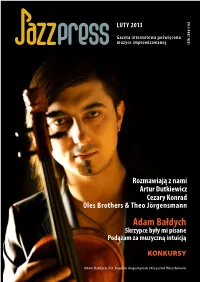

LUTY 2013 Gazeta internetowa poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej 2084-3143 ISSN Rozmawiają z nami Artur Dutkiewicz Cezary Konrad Oles Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann Adam Bałdych Skrzypce były mi pisane Podążam za muzyczną intuicją KONKURSY Adam Bałdych, fot. Bogdan Augustyniak i Krzysztof Wierzbowski SPIS TREŚCI 3 – Od Redakcji 40 – Publicystyka 40 Felieton muzyczny Macieja Nowotnego 4 – KONKURSY O tym, dlaczego ona tańczy NIE dla mnie... 6 – Co w RadioJAZZ.FM 42 Najciekawsze z najmniejszych w 2012 6 Jazz DO IT! 44 Claude Nobs 12 – Wydarzenia legendarny twórca Montreux Jazz Festival 46 Ravi Shankar 14 – Płyty Geniusz muzyki hinduskiej 14 RadioJAZZ.FM poleca 48 Trzeci nurt – definicja i opis (część 3) 16 Nowości płytowe 50 Lektury (nie tylko) jazzowe 22 Pod naszym patronatem Reflektorem na niebie wyświetlimy napis 52 – Wywiady Tranquillo 52 Adam Baldych 24 Recenzje Skrzypce były mi pisane Walter Norris & Leszek Możdżer Podążam za muzyczną intuicją – The Last Set Live at the a – Trane 68 Cezary Konrad W muzyce chodzi o emocje, a nie technikę 26 – Przewik koncertowy 77 Co słychać u Artura Dutkiewicza? 26 RadioJAZZ.FM i JazzPRESS zapraszają 79 Oles Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann 27 Koncerty w Polsce Transgression to znak, że wspięliśmy się na 28 Nasi zagranicą nowy poziom 31 Ulf Wakenius & AMC Trio 33 Oleś Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann tour 83 – BLUESOWY ZAUŁEK Obłędny klarnet w magicznym oświetleniu 83 29 International Blues Challenge 35 Extra Ball 2, czyli Śmietana – Olejniczak 84 Magda Piskorczyk Quartet 86 T-Bone Walker 37 Yasmin Levy w Palladium 90 – Kanon Jazzu 90 Kanon w eterze Music for K – Tomasz Stańko Quintet The Trio – Oscar Peterson, Joe Pass, Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen 95 – Sesje jazzowe 101 – Redakcja Możesz nas wesprzeć nr konta: 05 1020 1169 0000 8002 0138 6994 wpłata tytułem: Darowizna na działalność statutową Fundacji JazzPRESS, luty 2013 Od Redakcji Czas pędzi nieubłaganie i zaskakująco szybko. -

Keeping the Tradition by Marilyn Lester © 2 0 1 J a C K V

AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM P EE ING TK THE R N ADITIO DARCY ROBERTA JAMES RICKY JOE GAMBARINI ARGUE FORD SHEPLEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : ROBERTA GAMBARINI 6 by ori dagan [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : darcy james argue 7 by george grella General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : preservation hall jazz band 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ricky ford by russ musto Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : joe shepley 10 by anders griffen [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : weekertoft by stuart broomer US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 31 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Event Calendar 32 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mathieu Bélanger, Marco Cangiano, Ori Dagan, George Grella, George Kanzler, Annie Murnighan Contributing Photographers “Tradition!” bellowed Chaim Topol as Tevye the milkman in Fiddler on the Roof.