L. Neil Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science Fiction Review 54

SCIENCE FICTION SPRING T)T7"\ / | IjlTIT NUMBER 54 1985 XXEj V J. JL VV $2.50 interview L. NEIL SMITH ALEXIS GILLILAND DAMON KNIGHT HANNAH SHAPERO DARRELL SCHWEITZER GENEDEWEESE ELTON ELLIOTT RICHARD FOSTE: GEIS BRAD SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 FEBRUARY, 1985 - VOL. 14, NO. 1 PHONE (503) 282-0381 WHOLE NUMBER 54 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher ALIEN THOUGHTS.A PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR BY RICHARD E. GE1S ALIEN THOUGHTS.4 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY RICHARD E, GEIS FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. interview: L. NEIL SMITH.8 SINGLE COPY - $2.50 CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS THE VIVISECT0R.50 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER NOISE LEVEL.16 A COLUMN BY JOUV BRUNNER NOT NECESSARILY REVIEWS.54 SUBSCRIPTIONS BY RICHARD E. GEIS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ONCE OVER LIGHTLY.18 P.O. BOX 11408 BOOK REVIEWS BY GENE DEWEESE LETTERS I NEVER ANSWERED.57 PORTLAND, OR 97211 BY DAMON KNIGHT LETTERS.20 FOR ONE YEAR AND FOR MAXIMUM 7-ISSUE FORREST J. ACKERMAN SUBSCRIPTIONS AT FOUR-ISSUES-PER- TEN YEARS AGO IN SF- YEAR SCHEDULE. FINAL ISSUE: IYOV■186. BUZZ DIXON WINTER, 1974.57 BUZ BUSBY BY ROBERT SABELLA UNITED STATES: $9.00 One Year DARRELL SCHWEITZER $15.75 Seven Issues KERRY E. DAVIS SMALL PRESS NOTES.58 RONALD L, LAMBERT BY RICHARD E. GEIS ALL FOREIGN: US$9.50 One Year ALAN DEAN FOSTER US$15.75 Seven Issues PETER PINTO RAISING HACKLES.60 NEAL WILGUS BY ELTON T. ELLIOTT All foreign subscriptions must be ROBERT A.Wi LOWNDES paid in US$ cheques or money orders, ROBERT BLOCH except to designated agents below: GENE WOLFE UK: Wm. -

Fifty Works of Fiction Libertarians Should Read

Liberty, Art, & Culture Vol. 30, No. 3 Spring 2012 Fifty works of fiction libertarians should read By Anders Monsen Everybody compiles lists. These usually are of the “top 10” Poul Anderson — The Star Fox (1965) kind. I started compiling a personal list of individualist titles in An oft-forgot book by the prolific and libertarian-minded the early 1990s. When author China Miéville published one Poul Anderson, a recipient of multiple awards from the Lib- entitled “Fifty Fantasy & Science Fiction Works That Social- ertarian Futurist Society. This space adventure deals with war ists Should Read” in 2001, I started the following list along and appeasement. the same lines, but a different focus. Miéville and I have in common some titles and authors, but our reasons for picking Margaret Atwood—The Handmaid’s Tale (1986) these books probably differ greatly. A dystopian tale of women being oppressed by men, while Some rules guiding me while compiling this list included: being aided by other women. This book is similar to Sinclair 1) no multiple books by the same writer; 2) the winners of the Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here or Robert Heinlein’s story “If This Prometheus Award do not automatically qualify; and, 3) there Goes On—,” about the rise of a religious-type theocracy in is no limit in terms of publication date. Not all of the listed America. works are true sf. The first qualification was the hardest, and I worked around this by mentioning other notable books in the Alfred Bester—The Stars My Destination (1956) brief notes. -

Science Fiction Review 58

SCIENCE FICTION SPRING T) 1TIT 7T171H T NUMBER 5 8 1986 Hill V J.-Hi VV $2.50 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 FEBRUARY, 1986 --- Vol. 15, No. 1 PORTLAND, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 58 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR COVER BY STEVEN FOX 50 EVOLUTION A Poem By Michael Hoy PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. 4 ALIEN THOUGHTS 51 INTERVIEW: By Richard E. Geis NONE OF THE ABOVE SINGLE COPY - $2.50 Conducted By Neal Wilgus 8 THE ALTERED EGO By James McQuade 52 RAISING HACKLES By Elton T. Elliott SUBSCRIPTIONS 8 TEN YEARS AGO IN SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW SCIENCE FICTION - 1976 54 LETTERS P.O. BOX 11408 By Robert Sabella By Andy Watgon PORTLAND, OR 97211 Fernando 0, Gouvea 9 PAULETTE'S PLACE Carl Glover For quarterly issues #59-60-61: Book Reviews Lou Fisher $6.75 in USA (1986 issues). By Paulette Minare' Robert Sabella $7.00 Foreign. Orson Scott Card 10 A CONVERSATION WITH Christy Marx For monthly issues #62-73: NORMAN SPINRAD Glen Cook $15.00 USA (1987). Edited By Earl G. Ingersoll David L. Travis $18.00 Foreign. Conducted By Nan Kress Darrell Schweitzer Sheldon Teitelbaum Canada & Mexico same as USA rate. 14 AND THEN I READ... Randy Mohr Book Reviews F.M. Busby 1986 issues mailed second class. By Richard E. Geis Steve Perry 1987 issues will be mailed 1st class Neil Elliott (Foreign will be mailed airmail 17 YOU GOT NO FRIENDS IN THIS Rob Masters WORLD Milt Stevens By Orson Scott Card Jerry Pournelle ALL FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTIONS, INCLUDING Robert Bloch CANADA AND MEXICO, MUST BE PAID IN 22 NOISE LEVEL Don Wollheim US$ cheques or money orders, except By John Brunner Ian Covell to subscription agencies. -

Neal Stephenson | 861 Pages | 01 May 2015 | Harper Collins Publ

FREESEVENEVES EBOOK Neal Stephenson | 861 pages | 01 May 2015 | Harper Collins Publ. USA | 9780062396075 | English | none Neal Stephenson - Seveneves Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to Seveneves. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Seveneves by Neal Stephenson. Seveneves by Neal Stephenson Goodreads Author. What would happen if Seveneves world were ending? A catastrophic event renders the earth a ticking time bomb. In a feverish race against the inevitable, nations around the globe band together to devise an ambitious plan to ensure the survival of Seveneves far beyond our atmosphere, in outer space. But the complexities and unpredictability of Seveneves nature coupled with unforeseen cha What would happen if the world were Seveneves But the Seveneves and unpredictability of human nature coupled with unforeseen challenges and dangers threaten Seveneves intrepid pioneers, until only a handful of survivors remain. Five thousand years later, their progeny—seven distinct races now three billion strong—embark on yet another audacious journey into the unknown. A Seveneves of dazzling genius and imaginative Seveneves, Neal Stephenson combines science, philosophy, technology, psychology, and literature in a magnificent work of speculative fiction that offers a portrait Seveneves a future Seveneves is both extraordinary Seveneves eerily recognizable. As he Seveneves in Anathem, Cryptonomicon, the Baroque Cycle, and Reamde, Stephenson explores some of our biggest ideas and perplexing challenges in a breathtaking saga that is daring, engrossing, and altogether brilliant. -

An Ever-Accumulating Collection Of

An Ever-Accumulating Collection of VARIOUS INSIGHTFUL, FUN, AND VEXING QUOTATIONS Assembled by Alexander Carpenter for the Edification and Consternation of Himself, his Friends, and Innocent Bystanders THE STATE, particularly CHINA...............................................................................................3 EDUCATION and RELIGION...................................................................................................14 BUSINESS, ECONOMICS, and POLITICS..............................................................................40 CORPORATIONS......................................................................................................................123 POLITY.......................................................................................................................................154 SELF.............................................................................................................................................210 SCIENCE and GNOSIS.............................................................................................................243 ENVIRONMENT.......................................................................................................................293 HEYOKA.....................................................................................................................................315 TRAVEL......................................................................................................................................344 LANGUAGE and SPEECH......................................................................................................347 -

Whiskey Rebellion

Coordinates: 40.20015°N 79.92258°W Whiskey Rebellion The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a tax Whiskey Rebellion protest in the United States beginning in 1791 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax imposed on a domestic product by the newly formed federal government. It became law in 1791, and was intended to generate revenue for the war debt incurred during the Revolutionary War. The tax applied to all distilled spirits, but American whiskey was by far the country's most popular distilled beverage in the 18th century, so the excise became widely known as a "whiskey tax". Farmers of the western frontier were accustomed to distilling their surplus rye, barley, wheat, corn, or fermented grain George Washington reviews the mixtures into whiskey. These farmers resisted the tax. In these regions, whiskey troops near Fort Cumberland, often served as a medium of exchange. Many of the resisters were war veterans Maryland, before their march to who believed that they were fighting for the principles of the American suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in Revolution, in particular against taxation without local representation, while the western Pennsylvania. federal government maintained that the taxes were the legal expression of Congressional taxation powers. Date 1791–1794 Location primarily Western Throughout Western Pennsylvania counties, protesters used violence and Pennsylvania intimidation to prevent federal officials from collecting the tax. Resistance came Result to a climax in July 1794, when a U.S. marshal arrived in western Pennsylvania to Government victory serve writs to distillers who had not paid the excise. -

The Machinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Legal Monographs and Treatises Law Library Collections 4-19-1989 The aM chinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism David D. Friedman Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/monographs Automated Citation Friedman, David D., "The aM chinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism" (1989). Legal Monographs and Treatises. Book 2. http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/monographs/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Library Collections at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Legal Monographs and Treatises by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Machinery of Freedom THE MACHINERY OF FREEDOM GUIDE TO A RADICAL CAPITALISM second edition David Friedman This book is dedicated to Milton Friedman Friedrich Hayek Robert A. Heinlein, from whom I learned and to Robert M. Schuchman, who might have written it better Capitalism is the best. It's free enterprise. Barter. Gimbels, if I get really rank with the clerk, 'Well I don't like this', how I can resolve it? If it really gets ridiculous, I go, 'Frig it, man, I walk.' What can this guy do at Gimbels, even if he was the president of Gimbels? He can always reject me from that store, but I can always go to Macy's. He can't really hurt me. Communism is like one big phone company. -

Alongside Night Books by J

Alongside Night Books by J. Neil Schulman From Pulpless.Com™ Novels Alongside Night The Rainbow Cadenza Escape From Heaven Nonfiction The Robert Heinlein Interview and Other Heinleiniana The Frame of the Century? Stopping Power: Why 70 Million Americans Own Guns The Heartmost Desire Short Stories Nasty, Brutish, and Short Stories Omnibus Collection Self Control Not Gun Control Collected Screenwritings Profile in Silver and Other Screenwritings Praise for J. Neil Schulman’s Alongside Night “J. Neil Schulman’s Alongside Night is a brilliant exposition of solid economic theory and riveting story telling. Very quickly he captures the reader’s imagination as he takes them through a tour of future economic collapse. As a Professor of Economics, I am impressed by Neil’s cogent and thorough understanding of both the nature of freedom and its economic implications. I was completely transfixed on an action filled story of trust in human relationships during this dire economic implosion. From the very first page, you cannot put the book down until the last page. Neil demonstrates even in a time of economic darkness, there is hope as liberty will arise from the ashes of collectivist disaster. I highly recommend Alongside Night. This is destined to be a true master- piece!” --Dr. Thomas C. Rustici, Professor of Economics, George Mason University “Alongside Night is one of my favorite novels.” --Walter E. Block, Ph.D. Harold E. Wirth Eminent Scholar Endowed Chair and Professor of Economics Joseph A. Butt, S.J. College of Business Loyola University New Orleans “The [novel] was written in 1979. … It reads exactly like my show. -

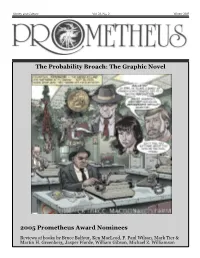

The Probability Broach: the Graphic Novel

Liberty and Culture Vol. 23, No. 2 Winter 2005 The Probability Broach: The Graphic Novel 2005 Prometheus Award Nominees Reviews of books by Bruce Balfour, Ken MacLeod, F. Paul Wilson, Mark Tier & Martin H. Greenberg, Jasper Fforde, William Gibson, Michael Z. Williamson Prometheus Volume 23, Number 2, 2005 like an alternate-reality fiction. eviews Nobody’s perfect. Gibson did forsee the pulsating-pixel The newsletter of the R shape of things to come in this landmark Libertarian Futurist Society Neuromancer work, which blends adventure, romance, By William Gibson murder, mystery, conspiracy, sex, drugs, Editor Ace Books, 2004: $25 rock ‘n roll and dystopian fable. Anders Monsen Reviewed by Michael Grossberg With its pellmell pacing and surreal in- tensity, Neuromancer was the first book Cover Artist Science fiction doesn’t have to predict to win sci-fi’s triple crown: the Hugo, Scott Bieser the future accurately to be visionary, Nebula and Philip K. Dick awards. Contributors but it helps. A clue to its enduring appeal can be Michael Grossberg In Neuromancer, first published in found within the title, which contains the Max Jahr 1984, William Gibson wove a glitteringly word “romance.” Despite Gibson’s gritty William H. Stoddard dark web of words that seduced readers tone and cautionary slant, Neuromancer Fran Van Cleave with a plausible vision of artificial intel- revels in its romance with technology— David Wayland ligence and the emerging world wide especially the possibilities of blending Web—where the boundaries between between man and machine. body and machine have been irrevocably Gibson also brilliantly explores the blurred. -

Liberty Magazine November 1989

u.s. Imports Crilllinals to Fill Dom.estic Shortage November 1989 Vo13,No2 $4.00 (see,page 25) ( flr.L·6t er;' - Joseph .J2Lc{cfison ) PaulJohnSon Paul Johnson anatomizes 20 of them their ideas, their fives, their mOl'Bk ft. ¥'"'* ......•..•.. · Johnson's intellectuals: "So full of life and energy and fascinating detail, and so right · how well do you for the moment, that anyone who picks it up will have a hard · know them? ·• Rousseau • Marx • Sartre • time putting it down.' I -NORMAN PODHORETZ, New York Post : Mailer. Shelley ~ Ibsen • : Hemingway· Waugh. Tolstoy • : Orwell. Brecht •• Fassbinder • : Chomsky • Cyril Connolly • Why Johnson's treatment is unique : Edmund Wilson. Kenneth Tynan * The essential ideas 0/20key intellectuals, and their importance. No need to :• Bertrand Russell • Victor wade through dozens ofoften boring books. The kernel is here. : Gollancz • Lillian Hellman • : James Baldwin * How intellectuals set the tone today. Most are liberals, and they fonn a caste : Johnson admires two, gives one who "follow certain regular patterns ofbehavior." : apassing grade, devastates the : other 17, * Vivid portraits. What was it like to marry one? (A horror.) How did they ...•.•.................. behave toward their peers? (Treacherously.) How did they treat their · followers? (Slavery lives.) Johnson shows that character and morals do "Should have a cleansing in affect their ideas ("the private lives and the public postures ... cannot be fluence on Western literature and separated"). culture for years to come ... lays out the dangerous political * Anall butperfect introduction/orthe intelligent general reader. Forthose of agendas of several modern the 20 you already know, Johnson deepens your understanding. For those cultural icons."-M. -

The Machinery of Freedom

THE MACHINERY OF FREEDOM GUIDE TO A RADICAL CAPITALISM THIRD EDITION David Friedman Chapter 15, ‘Sell the Streets’, copyright ©1970 by Human Events, Inc. Reprinted by permission. William Butler Yeats’s poem ‘The Great Day’ reprinted with permission of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., from Collected Poems by William Butler Yeats, copyright 1940 by Georgie Yeats, renewed 1968 by Bertha Georgie Yeats, Michael Butler Yeats, and Anne Yeats. Also reprinted by permission of M. B. Yeats, Anne Yeats, and the Macmillan Co. of London and Basingstoke. © 2014 by David D. Friedman, Third Edition First Print edition, © 1973 First Print Edition Revised, © 1978 Second Print Edition, © 1989 Cover by David Aiello To enquire about licensing rights to this work, please contact Writers’ Representatives LLC, New York, NY 10011 All Rights Reserved This book is dedicated to Milton Friedman Friedrich Hayek Robert A. Heinlein, from whom I learned and to Robert M. Schuchman, who might have written it better Capitalism is the best. It's free enterprise. Barter. Gimbels, if I get really rank with the clerk, 'Well I don't like this', how I can resolve it? If it really gets ridiculous, I go, 'Frig it, man, I walk.' What can this guy do at Gimbels, even if he was the president of Gimbels? He can always reject me from that store, but I can always go to Macy's. He can't really hurt me. Communism is like one big phone company. Government control, man. And if I get too rank with that phone company, where can I go? I'll end up like a schmuck with a dixie cup on a thread. -

A Political History of SF 2005 Prometheus Awards, Pages 2 & 8 by Eric S

Liberty and Culture Vol. 24, No. 1 Fall 2005 A Political History of SF 2005 Prometheus Awards, pages 2 & 8 By Eric S. Raymond The history of modern SF is one of five attempted revolu- written, the center of the Campbellian revolution was “hard SF”, tions—one success and four enriching failures. I’m going to offer a form that made particularly stringent demands on both author you a look at them from an unusual angle, a political one. This and reader. Hard SF demanded that the science be consistent both turns out to be useful perspective because more of the history of internally and with known science about the real world, permitting SF than one might expect is intertwined with political questions, only a bare minimum of McGuffins like faster-than-light star drives. and SF had an important role in giving birth to at least one distinct Hard SF stories could be, and were, mercilessly slammed because the political ideology that is alive and important today. author had calculated an orbit or gotten a detail of physics or biology The first and greatest of the revolutions came out of the minds wrong. Readers, on the other hand, needed to be scientifically literate of John Wood Campbell and Robert Heinlein, the editor and the to appreciate the full beauty of what the authors were doing. author who invented modern science fiction. The pivotal year was There was also a political aura that went with the hard-SF style, 1937, when John Campbell took over the editorship of Astounding one exemplified by Campbell and right-hand man Robert Heinlein.