Sweet Springs, Wv: the Architecture of Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England

'? '/-'#'•'/ ' ^7 f CX*->C5CS- '^ OF CP^ 59§70^ l-SSi"-.". -,, 3 ,.. -SJi f, THE LEGENDARY LORE OF THE HOL Y WELLS OF ENGLAND. : THE LEGENDARY LORE ' t\Q OF THE ~ 1 T\ I Holy Wells of England: INCLUDING IRfpers, Xaftes, ^fountains, ant) Springs. COPIOUSLY ILLUSTRATED BY CURIOUS ORIGINAL WOODCUTS. ROBERT CHARLES HOPE, F.S.A., F.R.S.L., PETERHOUSE, CAMBRIDGE; LINCOLN'S INN; MEMBER,OF THE COUNCIL OF THE EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY, AUTHOR OF "a GLOSSARY OF DIALECTAL PLACE-NOMENCLATURE," " AN INVENTORY OF THE CHURCH PLATE IN RUTLAND," "ENGLISH GOLDSMITHS," " THE LEPER IN ENGLAND AND ENGLISH LAZAR-HOUSES ;" EDITOR OF BARNABE GOOGE'S " POPISH KINGDOME." LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1893. PREFACE, THIS collection of traditionary lore connected with the Holy Wells, Rivers, Springs, and Lakes of England is the first systematic attempt made. It has been said there is no book in any language which treats of Holy Wells, except in a most fragmentary and discursive manner. It is hoped, therefore, that this may prove the foundation of an exhaustive work, at some future date, by a more competent hand. The subject is almost inexhaustible, and, at the same time, a most interesting one. There is probably no superstition of bygone days that has held the minds of men more tenaciously than that of well-worship in its broadest sense, "a worship simple and more dignified than a senseless crouching before idols." An honest endeavour has been made to render the work as accurate as possible, and to give the source of each account, where such could be ascertained. -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Holy Wells" in Scotland

2 15 PROCEEDING SSOCIETYE 01TH ' , FEBRUARY 12, 1883. IV. "HOLY WELLS" IN SCOTLAND. BY J. RUSSEL WALKER, ARCHITECT, F.S.A. SCOT. The virtues of water seem to have been recognised by every tribe and people, and resort to fountains has apparently been universal in all ages, " combining as it does medicine and mythology, the veneration of the sanctified wite relieth h f expected through their mediation.e Th " Egyptians, from time immemoria tho lt e present day, have veneratee dth waters fro benefite mth s imparted by- them. Neptune e greath , t marine deity, had bulls sacrificed to him. Aristotle speaks of the fountain Palica in Sicily, " wherein billets floate f i inscribed d with truth t thebu ;y were.absorbed, and the perjured perished by fire, if bearing false affirma- tions." " Theft was betrayed by the sinking of that billet inscribed with the name of the suspected thief, thrown with others among holy water." Virgil claim e indulgencsth f Arethusaeo e JewTh s, were possessef o d hol o enterey wh e poolpoo d wellse th f dBethesdo an H ls . a first, after it had been disturbed by an angel, was cured of his distemper." e JordaTh s alsni a osanctifie d stream d thousandan , pilsn o stil- o g l grimage to perform their ablutions in it. The savage tribes of America worshipped the spirit of the waters, and left their persenal ornaments as votive offerings. The ancients, alike Greek d Romanssan , worshipped divinitie fountainse th f so d erectean , d temples and statues in their honour. -

The Isle of Wight, C. 1750-1840: Aspects of Viewing, Recording And

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES Department of Archaeology The Isle of Wight, c.1750-1840: Aspects of Viewing, Recording and Consumption. by Stewart Abbott Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2006 ii University of Southampton ABSTRACT SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Doctor of Philosophy THE ISLE OF WIGHT, c.1750-1840: ASPECTS OF VIEWING, RECORDING AND CONSUMPTION by Stewart Abbott The main areas of Picturesque Travel during the second half of the long eighteenth century were the Lake District, Wales, Scotland and the Isle of Wight; of these locations the Isle of Wight has been the least reviewed. This study examines Island-centred historical and topographical material published 1750-1840 in conjunction with journals and diaries kept by contemporary visitors. -

Master John Shorne

MASTER JOHN SHORNE. The village of North Marston, which has lately become somewhat celebrated for a memorial window, raised by the Queen to John Camden Neild, who bequeathed to her Majesty his ample property, was once far more celebrated for the memorials which it contained of Master John Shorne. This notable personage, though not to be found in the Roman Calendar, was once an acknowledged Saint, as clearly appears even from the few disjointed notices of him which still remain. He is sometimes called Sir John, and Saint John, but more commonly Master John Shorne. Having previously been rector of Monks Risborough, he was presented to North Marston, in the year 1290, and continued to hold this rectory till his death. While at North Marston he became renowned, far and near, for his uncommon piety and miraculous powers. In proof of his sanctity, tradition informs us that "his knees became horny, from the frequency of his prayersand in proof of his miraculous powers, two great facts, in particular, are recorded. There is still at Marston a " Holy Well," which, by virtue of his benediction, is said to have been endowed with healing properties. But the principal achievement of his faith—the one great act of his life— was the imprisoning the devil within one of his boots. This was the astounding miracle which raised him to the dignity of a Saint, and won for him the veneration of cen- turies. How he accomplished this extraordinary feat;— how long he retained his prisoner in " durance vile— and how far sin and crime were diminished, during the captivity, neither record nor tradition informs us. -

SKIDMORE LEAD MINERS of DERBYSHIRE, and THEIR DESCENDANTS 1600-1915 Changes Were Made to This Account by Linda Moffatt on 19 February 2019

Skidmore Lead Miners of Derbyshire & their descendants 1600-1915 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKIDMORE LEAD MINERS OF DERBYSHIRE, AND THEIR DESCENDANTS 1600-1915 Changes were made to this account by Linda Moffatt on 19 February 2019. by Linda Moffatt Parrsboro families have been transferred to Skydmore/ Scudamore Families of Wellow, 2nd edition by Linda Moffatt© March 2016 Bath and Frome, Somerset, from 1440. 1st edition by Linda Moffatt© 2015 This is a work in progress. The author is pleased to be informed of errors and omissions, alternative interpretations of the early families, additional information for consideration for future updates. She can be contacted at [email protected] DATES • Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. • Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

Transactions Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural

TRANSACTIONS of the DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY and ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY FOUNDED 20 NOVEMBER 1862 THIRD SERIES VOLUME 91 XCI Editors: DAVID F. DEVEREUX JAMES FOSTER ISSN 0141-1292 2017 DUMFRIES Published by the Council of the Society Office-Bearers 2016–2017 and Fellows of the Society President Dr Jeremy Brock Vice Presidents Mrs P.G. Williams, Mr R. Copland, Mr D. Dutton and Mr M. Cook Fellows of the Society Mr A.D. Anderson, Mr J.H.D. Gair, Dr J.B. Wilson, Mr K.H. Dobie, Mrs E. Toolis, Dr D.F. Devereux, Mrs M. Williams, Dr F. Toolis, Mr L. Murray and Mr L.J. Masters Hon. Secretary Mr J.L. Williams, Merkland, Kirkmahoe, Dumfries DG1 1SY Hon. Membership Secretary Mr S. McCulloch, 28 Main Street, New Abbey, Dumfries DG2 8BY Hon. Treasurer Mrs A. Weighill Hon. Librarian Mr R. Coleman, 2 Loreburn Park, Dumfries DG1 1LS Hon. Institutional Subscriptions Secretary Mrs A. Weighill Hon. Editors Mrs E. Kennedy, Nether Carruchan, Troqueer, Dumfries DG2 8LY Dr J. Foster (Webmaster), 21 Maxwell Street, Dumfries DG2 7AP Hon. Syllabus Conveners Miss S. Ratchford, Tadorna, Hollands Farm Road, Caerlaverock, Dumfries DG1 4RS Mrs A. Clarke, 4 Redhall Road, Templand, Lockerbie DG11 1TF Hon. Curators Mrs J. Turner and Miss S. Ratchford Hon. Outings Organisers Mr D. Dutton Ordinary Members Dr Jeanette Brock, Mr D. Scott and Mr J. McKinnell CONTENTS A Case of Mistaken Identity? Monenna and Ninian in Galloway and the Central Belt by Oisin Plumb .................................................................. 9 Angles and Britons around Trusty’s Hill: some onomastic considerations by Alan James .................................................................................................... -

Baseline Groundwater Chemistry of Aquifers in England and Wales: The

Baseline groundwater chemistry of aquifers in England and Wales: the Carboniferous Limestone aquifer of the Derbyshire Dome Groundwater Programme Open Report OR/08/028 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GROUNDWATER PROGRAMME OPEN REPORT OR/08/028 Baseline groundwater chemistry of aquifers in England and Wales: Keywords Baseline, Carboniferous the Carboniferous Limestone Limestone, Derbyshire Dome, water quality, hydrogeochemistry, UK aquifer. aquifer of the Derbyshire Dome Front cover Carboniferous Limestone outcrop at Shining Bank Quarry C Abesser and P L Smedley [422850 364940] Bibliographical reference ABESSER, C. AND SMEDLEY, P.L.. 2008. Baseline groundwater chemistry of aquifers in England and Wales: the Carboniferous Limestone aquifer of the Derbyshire Dome. British Geological Survey Open Report, OR/08/028. 66 pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. This report includes maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey topographic material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of The Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction -

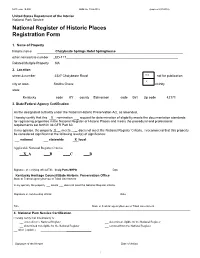

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property historic name Chalybeate Springs Hotel Springhouse other names/site number _ED-117______________________________________________________________ Related Multiple Property NA 2. Location street & number 2327 Chalybeate Road NA not for publication X city or town Smiths Grove vicinity state Kentucky code KY county Edmonson code 061 zip code 42171 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide X local Applicable National Register Criteria: __X_A ___B _ __C ___D Signature of certifying official/Title Craig Potts/SHPO Date Kentucky Heritage Council/State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting official Date Title State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government 4. National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register determined eligible for the National Register determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain:) _________________ Signature of the Keeper Date of Action 1 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. -

Ire Iviiscellany

IRE IVIISCELLANY u&, t* 4 , i, DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY Volume 15: Part 4 Autumn 1999 CONTENTS Page Notes on the supposed Roman Baths at Buxton 94 by J.T. Leach The Public Record Oft'ice Catalogue on the Internet 1"14 .15 lohn Farey's Derbyshire: Derbyshire sheep farming in the early 1 nineteenth century by Roger Dalton Melbourne Water Supply 121 by Howard Usher ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR TREASURER Jane Steer Dudley Fowkes T.J. Larimore 478 Duffield Road, 2 Mill Close, 43 Reginald Road South Allestree, Swanwick, Chaddesden, Derby, Derbyshire, Derby, DE222DI DE55 1AX DE21 6NG Copyright in each contribution to Derbyshire Miscellany is reserved by the author. ISSN 0417 0ri87 93 NOTES ON THE SUPPOSED ROMAN BATHS AT BUXTON (by J.T. Leach, 25 Atherton Way, Tiverton, Devon, EX16 4EW) 1. Introduction Situated at an altitude of 300 metres above sea level Buxton lies on the northern edge of the Carboniferous Limestone outcrop. The valley of the River Wye at this point has a large number of springs which issue from the limestone, and the sandstones and shales which form the valley sides. The great majority of these springs are cold ones but in four separate locations water issues at an appreciably higher temperature. Between the Gmrge Hotel and the river, and at the west end of Cavendish Circus chalybeate springs issue at 12.50C, and at the south end of Burlington Road another spring issues at 180. The most important are the celebrated springs at the foot of the Slopes and now underneath the Old Hall Hotel. These, amongst numerous cold ones, issue continuously at 27.50C,. -

A Portrayal of a Wood in Kesteven Richard G Jefferson

BOURNE WOOD A portrayal of a wood in Kesteven Richard G Jefferson With contributions from David Evans, Fraser Bradbury, Andrew Powers and Robert Lamin Bourne, Lincolnshire 2016 Author Richard G Jefferson With contributions from David Evans, Fraser Bradbury, Andrew Powers and Robert Lamin Design by Engy Elboreini Booklet production supported by 3 BOURNE WOOD A portrayal of a wood in Kesteven Richard G Jefferson 4 INTRODUCTION Bourne Wood is situated immediately west of the town of Bourne in the District of South Kesteven in the County of Lincolnshire. It is contiguous with Pillar Wood immediately to the east and in the north incorporates Fox Wood and to the south, Auster Wood. The woodland complex (including Pillar Wood) covers an area of around 300 hectares (741 acres) but for the purposes of this booklet, the focus is on the Forestry Commission (FC) owned Bourne/Fox Wood which amounts to around 225 ha (556 acres). It overlooks the town and the reclaimed fens to its east. It lies at altitudes between 20 and 50 metres with the land generally rising in an east to west direction. The wood is owned by the FC who manage it for timber production, wildlife and informal recreation. A voluntary group, the Friends of Bourne Wood (‘The Friends’), organise an annual programme of guided walks and events in the wood and promote its amenity and educational value. 5 Autumn view © Terry Barnatt Terry © view Autumn 6 Contents HISTORY & ARCHAEOLOGY �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 8 GEOLOGY AND SOILS �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Alexandra Park Conservation Plan

Alexandra Park Management and Development Plan 2017-27 Appendix B. Conservation and Restoration Plan Conservation and Restoration Plan 2017 – 2027 1 Alexandra Park Management and Development Plan 2017-27 Appendix B. Conservation and Restoration Plan Hastings Borough Council Environment and Place Muriel Matters House, Breeds Place, Hastings, East Sussex, TN34 3UY Executive Summary: Alexandra Park is by far the most important Public Park in Hastings and St. Leonards, but in the 1990’s had deteriorated to an extent, due to Local Government budget shortages and changing priorities. In 1999 a successful bid was made to the Heritage Lottery Fund for £3.5 million. This plan was drawn up to support the bid and provide the context for the bid, while outlining the historic importance of the park. It provided proposals for the restoration, many of which were subsequently implemented, although some objectives remain aspirational and subject to further funding. The diverse and varied nature of the park is what makes it so amazing, but it also makes management quite challenging. The significance of the varying areas of the park are described in the “Character Areas” section of this plan. In the next 10 years, Management will look for ways to preserve the restored park, while introducing more sustainable and effective practices. More needs to be done to ensure the next generation of Managers and Gardeners are properly trained and equipped in order to preserve the efforts of those before them. This Plan must be read in conjunction with the Management Plan that sets out ongoing development and maintenance details for the next 10 years.