Text Postscript 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Parish Magazine

THE PARISH MAGAZINE THE TYNDALE BENEFICE OF WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE WITH OZLEWORTH, NORTH NIBLEY AND ALDERLEY (INCLUDING TRESHAM) 70p per copy. £7 annually DECEMBER 2017 1 The Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Wotton-under-Edge; The Parish Church of St. Martin of Tours, North Nibley; The Church of St. Nicholas of Myra, Ozleworth; The Parish Church of St. Kenelm, Alderley; The Perry and Dawes Almshouses Chapel; The Chapel of Ease at Tresham. (North Nibley also publishes its own journal ‘On the Edge’) CLERGY: Vicar: Rev’d Canon Rob Axford, The Vicarage, Culverhay (01453-842 175) Assistant Curate: Rev’d Morag Langley (01453-845 147) Associate Priests: Rev’d Christine Axford, The Vicarage (01453-842 175) Rev’d Peter Marsh (01453 547 521 – not after 7.00pm) Licensed Reader: Sue Plant, 3 Old Town (01453-845 157) Clergy with permission to officiate: Rev’d John Evans ( 01453-845 320) Rev’d Canon Iain Marchant (01453-844 779) Parish Administrator: Kate Cropper, Parish Office Tues.-Thurs. 9.0-1.0 (01453-842 175) e-mail: [email protected] CHURCHWARDENS: Wotton: Alan Bell, 110 Parklands (01453-521 388) Jacqueline Excell, 94 Bearlands. (01453-845 178) North Nibley: Wynne Holcombe (01453-542 091} Alderley, including Robin Evans, ‘The Cottage’, Alderley (01453-845 320) Tresham: Susan Whitfield (01666-890 338) PARISH OFFICERS: Wotton Parochial Church Council: Hon. Secretary: Kate Cropper, Parish Office (01453-842 175) Hon. Treasurer Joan Deveney, 85 Shepherds Leaze (01453-844370) Stewardship Treasurer: Alan Bell,110 Parklands (01453-521 388) PCC -

Kingswood Environmental Character Assessment 2014

Kingswood Environmental Character Assessment October 2014 Produced by the Kingswood VDS & NDP Working Group on behalf of the Community of Kingswood, Gloucestershire Contents Purpose of this Assessment ............................................................................................................................... 1 Location ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Landscape Assessment ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Setting & Vistas .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Land Use and Landscape Pattern .................................................................................................................. 5 Waterways ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Landscape Character Type ............................................................................................................................. 8 Colour ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 Geology ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Gloucestershire Parish Map

Gloucestershire Parish Map MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT 1 Charlton Kings CP Cheltenham 91 Sevenhampton CP Cotswold 181 Frocester CP Stroud 2 Leckhampton CP Cheltenham 92 Sezincote CP Cotswold 182 Ham and Stone CP Stroud 3 Prestbury CP Cheltenham 93 Sherborne CP Cotswold 183 Hamfallow CP Stroud 4 Swindon CP Cheltenham 94 Shipton CP Cotswold 184 Hardwicke CP Stroud 5 Up Hatherley CP Cheltenham 95 Shipton Moyne CP Cotswold 185 Harescombe CP Stroud 6 Adlestrop CP Cotswold 96 Siddington CP Cotswold 186 Haresfield CP Stroud 7 Aldsworth CP Cotswold 97 Somerford Keynes CP Cotswold 187 Hillesley and Tresham CP Stroud 112 75 8 Ampney Crucis CP Cotswold 98 South Cerney CP Cotswold 188 Hinton CP Stroud 9 Ampney St. Mary CP Cotswold 99 Southrop CP Cotswold 189 Horsley CP Stroud 10 Ampney St. Peter CP Cotswold 100 Stow-on-the-Wold CP Cotswold 190 King's Stanley CP Stroud 13 11 Andoversford CP Cotswold 101 Swell CP Cotswold 191 Kingswood CP Stroud 12 Ashley CP Cotswold 102 Syde CP Cotswold 192 Leonard Stanley CP Stroud 13 Aston Subedge CP Cotswold 103 Temple Guiting CP Cotswold 193 Longney and Epney CP Stroud 89 111 53 14 Avening CP Cotswold 104 Tetbury CP Cotswold 194 Minchinhampton CP Stroud 116 15 Bagendon CP Cotswold 105 Tetbury Upton CP Cotswold 195 Miserden CP Stroud 16 Barnsley CP Cotswold 106 Todenham CP Cotswold 196 Moreton Valence CP Stroud 17 Barrington CP Cotswold 107 Turkdean CP Cotswold 197 Nailsworth CP Stroud 31 18 Batsford CP Cotswold 108 Upper Rissington CP Cotswold 198 North Nibley CP Stroud 19 Baunton -

South West West

SouthSouth West West Berwick-upon-Tweed Lindisfarne Castle Giant’s Causeway Carrick-a-Rede Cragside Downhill Coleraine Demesne and Hezlett House Morpeth Wallington LONDONDERRY Blyth Seaton Delaval Hall Whitley Bay Tynemouth Newcastle Upon Tyne M2 Souter Lighthouse Jarrow and The Leas Ballymena Cherryburn Gateshead Gray’s Printing Larne Gibside Sunderland Press Carlisle Consett Washington Old Hall Houghton le Spring M22 Patterson’s M6 Springhill Spade Mill Carrickfergus Durham M2 Newtownabbey Brandon Peterlee Wellbrook Cookstown Bangor Beetling Mill Wordsworth House Spennymoor Divis and the A1(M) Hartlepool BELFAST Black Mountain Newtownards Workington Bishop Auckland Mount Aira Force Appleby-in- Redcar and Ullswater Westmorland Stewart Stockton- Middlesbrough M1 Whitehaven on-Tees The Argory Strangford Ormesby Hall Craigavon Lough Darlington Ardress House Rowallane Sticklebarn and Whitby Castle Portadown Garden The Langdales Coole Castle Armagh Ward Wray Castle Florence Court Beatrix Potter Gallery M6 and Hawkshead Murlough Northallerton Crom Steam Yacht Gondola Hill Top Kendal Hawes Rievaulx Scarborough Sizergh Terrace Newry Nunnington Hall Ulverston Ripon Barrow-in-Furness Bridlington Fountains Abbey A1(M) Morecambe Lancaster Knaresborough Beningbrough Hall M6 Harrogate York Skipton Treasurer’s House Fleetwood Ilkley Middlethorpe Hall Keighley Yeadon Tadcaster Clitheroe Colne Beverley East Riddlesden Hall Shipley Blackpool Gawthorpe Hall Nelson Leeds Garforth M55 Selby Preston Burnley M621 Kingston Upon Hull M65 Accrington Bradford M62 -

Regulatory Board Commons and Rights of Way Panel 18 September 2003 Agenda Item: 6 Application for a Modification Order for an A

REGULATORY BOARD COMMONS AND RIGHTS OF WAY PANEL 18 SEPTEMBER 2003 AGENDA ITEM: 6 APPLICATION FOR A MODIFICATION ORDER FOR AN ADDITIONAL LENGTH OF BRIDLEWAY BETWEEN BRIMSCOOMBE WOOD AND SCRUBBETT'S LANE, SOUTH OF CONYGRE WOOD, NEWINGTON BAGPATH PARISHES OF KINGSCOTE AND OZLEWORTH JOINT REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: ENVIRONMENT AND THE HEAD OF LEGAL AND DEMOCRATIC SERVICES 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT To consider the following application: Nature of Application: Additional bridleway Parishes: Kingscote and Ozleworth Name of Applicants: Ben Harford and John Huntley Date of Application: 7 May 2002 2. RECOMMENDATION That a Modification Order be made to add the length of claimed bridleway to the Definitive Map. 3. RESOURCE IMPLICATIONS Average staff cost in taking an application to the Panel- £2,000. Cost of advertising Order in the local press, which has to be done twice, varies between £75 - £300 per notice. In addition, the County Council is responsible for meeting the costs of any Public Inquiry associated with the application. If the application were successful, the path would become maintainable at the public expense. 4. SUSTAINABILITY IMPLICATIONS No sustainability implications have been identified. 5. STATUTORY AUTHORITY Section 53 of the Wildlife. and Countryside Act 1981 imposes a duty on the County Council, as surveying authority, to keep the Definitive Map and Statement under continuous review and to modify it in consequence of the occurrence of an `event' specified in sub section [3]. Any person may make an application to the authority for a Definitive Map Modification Order on the occurrence of an `event' under section 53 [3] [b] or [c]. -

Country Houses of the Cotswolds 9

7 HE C OTSWOLD MANOR HOUSE and its setting assumed iconic status in the late nineteenth and early T twentieth centuries. At its most potent, it became a symbol of Edwardian nationalism, of the enduring values of ‘Old’ English civilisation itself, and of the unquestioned legiti- macy of a benevolent gentry class whose values were rooted in the land. This ideal was fostered from the start by Country Life, which was founded in 1897, and the magazine occupies a central place as a pioneer interpreter and forceful advocate of the Cotswold house and its landscape. Country Life Inspired by the dominant critique of William Morris, who urged the revival of vernacular styles, Country Life did much to discover and popularise the Cotswolds and to raise its fine houses to cult status. The first issues of the magazine featured tectural record. early manor houses, such as Chavenage, Chastleton, Stanway, Owlpen, Burford Priory, Cold Ashton Manor, and Daneway, Cotswold landscape some of them houses little known at that time, which The Cotswolds have never been a political or administrative reflected the emphasis of Edwardian taste on the Arcadian territory. They are geophysical: a chain of limestone hills setting, the authentic surface, and the unrestored slanting obliquely from north east to south west, on average ‘Tudorbethan’ interior. Under the influence of architects such some twenty miles wide. Today it is generally accepted that as Norman Shaw, Philip Webb and later Sir Edwin Lutyens, the Cotswolds extend fifty odd miles from the mound of the appeal broadened to include the Georgian vernacular of Meon Hill by Chipping Campden, in the north, to Lansdown houses such as Nether Lypiatt and Lyegrove. -

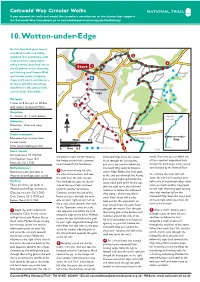

10. Wotton-Under-Edge

Cotswold Way Circular Walks If you enjoyed this walk and would like to make a contribution to the charity that supports the Cotswold Way then please go to cotswoldwayassociation.org.uk/fundraising/ 10. Wotton-under-Edge As rich farmland gives way to woodland tracks and rolling parkland, this enchanting walk 5 leads you from scarp top to 4 valley bottom, back into one of 1 the Cotswold’s most charming Start and thriving small towns. With Newark spectacular views, intriguing Park shops and historic architecture, B4058 all tastes will find something wonderful in this special little Wotton-under- corner of the Cotswolds... Edge B4060 Hawpark Distance: Farm 5 miles or 8 km (6½ or 10.4km Wortley 2 with detour to Newark Park). Hill Duration: Ley’s 3 - 4 hours (4 - 5 with detour) N Chipping Farm Campden Difficulty: Moderate - Stiles and steep Cotswold Way Wortley sections. Public transport: Wotton-under- Numerous bus services from Elmtree Farm 0 Miles 0.5 Edge various towns. (Visit www.travelinesw.com). Optional detour Bath 0 Kms 0.5 3 5/21 Start/Finish: Grid reference ST 755/932 the bottom right corner. Keeping Cotswold Way at the far corner. woods. From here you can follow any (OS Explorer sheet 167) the hedge on your left, continue Head through the kissing gate, of three excellent waymarked trails Postcode GL12 7DB round towards the farmhouse. and cross the road to follow the through this picturesque estate owned Refreshments: Cotswold Way towards Wotton- and managed by the National Trust. 2 Numerous pubs and cafés in Turn immediately left after under- Edge. -

4.4 Outlying Settlements of Monkham Thorns, New Mills, Chase Lane and Nind

“Shared access” roads for both pedestrians and vehicles in new development, to encourage children to play in street 4.4 Outlying Settlements of Monkham Thorns, New Mills, Chase Lane and Nind 4.4 a: Nind Map of Nind showing Link to Kingswood via Hillesley Road and Baldwins Green, The Cemetery, Nind Nature Reserve and the Ash Path I. Related to the very local community : A small rural hamlet which borders the parishes of Wotton-under-Edge and Alderley. A small residential settlement based immediately on either side of the narrow Nind Lane. The settlement borders the Ozleworth Brook, a tributary of the Little Avon. Some of the properties have gardens down to the water. There is a footpath which joins the hamlet to Kingswood via the Ash Path and in the other direction to a Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust Nature Reserve. II. Pattern and shape: The residential properties are based on both sides of the single carriageway lane, as shown in the example below, and many border onto the Ozleworth Brook. 77 The majority of the residential properties are located around a small track leading off Nind Lane, as shown below. 78 Nind Lane links from Hillesley Road in Kingswood to Wortley Road, below Little Tor Hill in Wotton- under-Edge. III. Nature of buildings and spaces: There is a working farm, Nind Farm, on the lane and the views are to fields used for agriculture, mainly grazing pasture. The fields are bordered by hedgerows. 79 There is an industrial site owned by Wotton Tarpaving immediately next to Nind Lane, close to its crossing over Ozleworth Brook The views are out towards Wotton and Alderley and are of an open rural aspect backed by the Cotswold Escarpment. -

COTSWOLD DISTRICT LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 (Adopted 3 August 2018)

COTSWOLD DISTRICT LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 (Adopted 3 August 2018) In memory of Tiina Emsley Principal Planning Policy Officer from 2007 to 2012 COTSWOLD DISTRICT LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 Contents 1 Introduction 6 2 Portrait 11 3 Issues 17 4 Vision 20 5 Objectives 21 6 Local Plan Strategy 23 6.1 Development Strategy (POLICY DS1) 23 6.2 Development Within Development Boundaries (POLICY DS2) 29 6.3 Small-Scale Residential Development in Non-Principal Settlements (POLICY DS3) 30 6.4 Open Market Housing Outside Principal and Non-Principal Settlements (POLICY DS4) 32 7 Delivering the Strategy 34 7.1 South Cotswold - Principal Settlements (POLICY SA1) 37 7.2 Cirencester Town (POLICY S1) 38 7.3 Strategic Site, south of Chesterton, Cirencester (POLICY S2) 44 7.4 Cirencester Central Area (POLICY S3) 47 7.5 Down Ampney (POLICY S4) 54 7.6 Fairford (POLICY S5) 57 7.7 Kemble (POLICY S6) 60 7.8 Lechlade (POLICY S7) 63 7.9 South Cerney (POLICY S8) 66 7.10 Tetbury (POLICY S9) 68 7.11 Mid Cotswold - Principal Settlements (POLICY SA2) 71 7.12 Andoversford (POLICY S10) 71 7.13 Bourton-on-the-Water (POLICY S11) 74 7.14 Northleach (POLICY S12) 77 7.15 Stow-on-the-Wold (POLICY S13) 80 7.16 Upper Rissington (POLICY S14) 82 Planning applications will be determined in accordance with relevant policies in this Local Plan, which should be considered together, unless material considerations indicate otherwise. COTSWOLD DISTRICT LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 Contents 7.17 North Cotswold - Principal Settlements (POLICY SA3) 84 7.18 Blockley (POLICY S15) 85 7.19 Chipping Campden (POLICY -

GLOUCESTERSHIRE. [Kl!:LLY's

364 WOTTON ST. MARY. GLOUCESTERSHIRE. [Kl!:LLY'S Cole Wm. farmer, Drymeadow farm Lane .Joseph, market gardener &; fnnr. Smith Charles, huntsman t{) the Long Cook George Ernest, market gardener, Norman place ford beagles, The Hawthorns, Inns- Springfield Moffatt Henry, farmer, Innsworth &; worth lane Crump Frederick, farmer, Bridge frm Paygrove farms; res. Kingsholm, Smith Edwin, shoe ma. Barnwood road Gardn8'l' John, timber dealer, saw mills Gloucester Stroud George Thomas, Cross Keys &c. Barnwood road Murrell Thomas, farmer &; market inn, Ba;rnwood road Goscomb Henry, market gardener, gardooer, Innsworth Vick In.frmr.Wotton frm.Barnwood rd Innsworth Perks Hy. Thos. dairyman, Springfield Vines Frank Martin,frmr.Oxstall's frm Rolle Edwin, dairyman, S'Pringfield Smallman Geo. shopkeepr.Old Tram rd Williams Alfred (MiI"i.), laundress, linITis Chas.mrkt.grdnr.Springfield vI Smart Jas. clerk ID the parish council Innsworth lane Kilminster Ernest, builder, I Prospect Smart James (Mrs.), laundress, Lmg villa, Ormscroft road Leavens WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE is a. town and parish and free lending library of Boo volumes at the Town Hall. head of a petty sessional division, 2l miles east-by-north The Church Institute has also extensive premises, includ from Charfield station on the Bristol and Birmingham ing a. Ia.rge lecture hall and reading and recreation rooms. section of the Midland railway, 19 south-south-west from The market, formerly held! on Friday, Ihas now fallen into Gloucester, 19 north-east from Bristol, 12 south-west disuse; but a pleasure fair is held annually, on Sept. 25. from Stroud, and loB from London, in the Mid division There are tw.o banks and t.hree good hotels, "The Swan," of the county, upper division of the hundred of Berkeley, "The l"alcon" and the "White Lion." The charities Dursley union and county court district, in the rural produce about £1,200 yearly. -

Owlpen Manor Gloucestershire

Owlpen Manor Gloucestershire A short history and guide to a romantic Tudor manor house in the Cotswolds Owlpen Press 2006 OWLPEN MANOR, Nr ULEY, GLOUCESTERSHIRE GL11 5BZ Ow lpe n Manor is one mile east of Uley, off the B4066, or approached from the B4058 Nailsworth to Wotton-under-Edge road: OS ref. ST800984. The manor house, garden and grounds are open on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays every week from 1st May to 30th September. Please check the up-to-date opening times (telephone: 01453-860261, or website: www.owlpen.com). There is a licensed restaurant in the fifteenth-century Cyder House, also available for functions, parties, weddings and meetings. There are nine holiday cottages on the Estate, including three listed historic buildings. Sleeping 2 to 10, they are available for short stays throughout the year. Acknowledgements When we acquired the manor and estate in 1974, we little realized what a formidable task it would be—managing, making, conserving, repairing, edifying—absorbing energies forever after. We would like to thank the countless people who have helped or encouraged, those with specialized knowledge and interests as well as those responsible, indefatigably and patiently, for the daily round. We thank especially HRH The Prince of Wales for gracious permission to quote from A Vision of Britain; long-suffering parents, children, and staff; David Mlinaric (interiors); Jacob Pot and Andrew Townsend (conservation architecture); Rory Young and Ursula Falconer (lime repairs); John Sales, Penelope Hobhouse and Simon Verity (gardens); Stephen Davis and Duff Hart-Davis (fire brigades); and Joan Gould and Martin Fairfax-Cholmeley (loans). -

6552 the London Gazette, 12 December, 1952

6552 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12 DECEMBER, 1952 NATIONAL PARKS AND ACCESS TO THE the undersigned before the 30th day of April, 1953, COUNTRYSIDE ACT, 1949. and any such objection or representation should state GLOUCESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL. the grounds on which it is made. NOTICE is hereby given that the Gloucestershire Dated the 3rd day of December, 1952. County Council has prepared a Draft Map of the GUY H. DAVIS, Clerk of the County Council. Rural District of Tetbury and Statement, by (249) Parishes, and that the places where copies may be inspected at all reasonable hours are as follows:— (i) County Surveyor's Office, Quay Street, NATIONAL PARKS AND ACCESS TO THE Gloucester. COUNTRYSIDE ACT, 1949. (ii) Tetbury R.D.C., Council Offices, Tetbury. GLOUCESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL. (iii) Parish (relating to Parish) and Place of NOTICE is hereby given that the Gloucestershire Inspection:— County Council has prepared a draft map of the borough of Cheltenham and statement, and the places Avening—No. 34, High Street, Avening. where copies may be inspected at all reasonable Beverston—Beverston Church Porch. hours are as follows: — Boxwell - with - Leighterton—Reading Room, (i) County Surveyor's Office, Quay Street, Leighterton. Gloucester. Cherington—Reading Room, Cherington. (ii) Cheltenham Municipal Offices, Cheltenham. Didmarton—The Rectory, Didmarton. Any objection or representation with respect to Kingscote—25, Kingscote Village, Tetbury. the draft map or statement may be sent in writing Long Newnton—Post Office, Long Newnton. to the undersigned before the 30th day of April, Ozleworth—Ozleworth Parish Church. 1953, and any such objection or representation should Shipton Moyne—Tetbury R.D.C.