Country Houses of the Cotswolds 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

468 KB Adobe Acrobat Document, Opens in A

Campden & District Historical and Archæological Society Regd. Charity No. 1034379 NOTES & QUERIES NOTES & QUERIES Volume VI: No. 1 Gratis Autumn 2008 ISSN 1351-2153 Contents Page From the Editor 1 Letters to the Editor 2 Maye E. Bruce Andrew Davenport 3 Lion Cottage, Broad Campden Olivia Amphlett 6 Sir Thomas Phillipps 1792-1872: Bibliophile David Cotterell 7 Rutland & Chipping Campden: an unexplained connection Tim Clough 9 Putting their hands to the Plough, part II Margaret Fisher 13 & Pearl Mitchell Before The Guild: Rennie Mackintosh Jill Wilson 15 ‘The Finest Street Left In England’ Carol Jackson 16 Christopher Whitfield 1902-1967 John Taplin 18 From The Editor As I start to edit this issue, I have just heard of the sad and unexpected death on 26th July after a very short illness, of Felicity Ashbee, aged 95, a daughter of Charles and Janet Ashbee. Her funeral was held on 6th August and there is to be a Memorial Tribute to her on 2nd October at the Art Workers Guild in London. Felicity has been the authority on her parents’ lives for many years now and her Obituary in the Independent described her as ‘probably the last close link with the inner circle of extraordinary creative talents fostered or inspired by William Morris’ … her death ‘marks its [the Arts & Crafts movement] formal and final passing’. This first issue of Volume Number VI is a bumper issue full of connections. John Taplin, Andrew Davenport and Tim Clough (Editor of Rutland Local History & Record Society), after their initial queries to the Archive Room, all sent articles on their researches; the pieces on Maye Bruce and Thomas Phillipps are connected with new publications; there is an ‘earthy’ connection between with the Plough, Rutland and Bruce researches and the Phillipps and Whitfield articles both have Shakespeare connections. -

The Parish Magazine

THE PARISH MAGAZINE THE TYNDALE BENEFICE OF WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE WITH OZLEWORTH, NORTH NIBLEY AND ALDERLEY (INCLUDING TRESHAM) 70p per copy. £7 annually DECEMBER 2017 1 The Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Wotton-under-Edge; The Parish Church of St. Martin of Tours, North Nibley; The Church of St. Nicholas of Myra, Ozleworth; The Parish Church of St. Kenelm, Alderley; The Perry and Dawes Almshouses Chapel; The Chapel of Ease at Tresham. (North Nibley also publishes its own journal ‘On the Edge’) CLERGY: Vicar: Rev’d Canon Rob Axford, The Vicarage, Culverhay (01453-842 175) Assistant Curate: Rev’d Morag Langley (01453-845 147) Associate Priests: Rev’d Christine Axford, The Vicarage (01453-842 175) Rev’d Peter Marsh (01453 547 521 – not after 7.00pm) Licensed Reader: Sue Plant, 3 Old Town (01453-845 157) Clergy with permission to officiate: Rev’d John Evans ( 01453-845 320) Rev’d Canon Iain Marchant (01453-844 779) Parish Administrator: Kate Cropper, Parish Office Tues.-Thurs. 9.0-1.0 (01453-842 175) e-mail: [email protected] CHURCHWARDENS: Wotton: Alan Bell, 110 Parklands (01453-521 388) Jacqueline Excell, 94 Bearlands. (01453-845 178) North Nibley: Wynne Holcombe (01453-542 091} Alderley, including Robin Evans, ‘The Cottage’, Alderley (01453-845 320) Tresham: Susan Whitfield (01666-890 338) PARISH OFFICERS: Wotton Parochial Church Council: Hon. Secretary: Kate Cropper, Parish Office (01453-842 175) Hon. Treasurer Joan Deveney, 85 Shepherds Leaze (01453-844370) Stewardship Treasurer: Alan Bell,110 Parklands (01453-521 388) PCC -

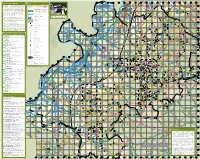

Places of Interest How to Use This Map Key Why Cycle?

76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 How to use this map Key The purpose of this map is to help you plan your route Cycleability gradations, in increasing difficulty 16 according to your own cycling ability. Traffic-free paths and pavements are shown in dark green. Roads are 1 2 3 4 5 graded from ‘quieter/easier’ to ‘busier/more difficult’ Designated traffic-free cycle paths: off road, along a green, to yellow, to orange, to pink, to red shared-used pavements, canal towpaths (generally hard surfaced). Note: cycle lanes spectrum. If you are a beginner, you might want to plan marked on the actual road surface are not 15 your journey along mainly green and yellow roads. With shown; the road grading takes into account the existence and quality of a cycle lane confidence and increasing experience, you should be able to tackle the orange roads, and then the busier Canal towpath, usually good surface pinky red and darker red roads. Canal towpath, variable surface Riding the pink roads: a reflective jacket Our area is pretty hilly and, within the Stroud District can help you to be seen in traffic 14 Useful paths, may be poorly surfaced boundaries, we have used height shading to show the lie of the land. We have also used arrows > and >> Motorway 71 (pointing downhill) to mark hills that cyclists are going to find fairly steep and very steep. Pedestrian street 70 13 We hope you will be able to use the map to plan One-way street Very steep cycling routes from your home to school, college and Steep (more than 15%) workplace. -

Stroud Labour Party

Gloucestershire County Council single member ward review Response from Stroud Constituency Labour Party Introduction On 30 November the Local Government Boundary Commission started its second period of consultation for a pattern of divisions for Gloucestershire. Between 30 November and 21 February the Commission is inviting comments on the division boundaries for GCC. Following the completion of its initial consultation, the Commission has proposed that the number of county councillors should be reduced from 63 to 53. The districts have provided the estimated numbers for the electorate in their areas in 2016; the total number for the county is 490,674 so that the average electorate per councillor would be 9258 (cf. 7431 in 2010). The main purpose of this note is to draw attention to the constraints imposed on proposals for a new pattern of divisions in Stroud district, which could lead to anomalies, particularly in ‘bolting together’ dissimilar district wards and parishes in order to meet purely numerical constraints. In it own words ‘the Commission aims to recommend a pattern of divisions that achieves good electoral equality, reflects community identities and interests and provides for effective and convenient local government. It will also seek to use strong, easily-identifiable boundaries. ‘Proposals should demonstrate how any pattern of divisions aids the provision of effective and convenient local government and why any deterioration in equality of representation or community identity should be accepted. Representations that are supported by evidence and argument will carry more weight with the Commission than those which merely assert a point of view.’ While a new pattern of ten county council divisions is suggested in this note, it is not regarded as definitive but does contain ways of avoiding some possible major anomalies. -

675 Minutes of the Meeting of Uley Parish Council Held on Wednesday

675 Minutes of the meeting of Uley Parish Council held on Wednesday 5 September 2018, commencing at 7.00pm in the Village Hall, Uley. PRESENT: Councillors Jonathan Dembrey (Chairman) Janet Wood (Vice-Chair) Melanie Paraskeva Mike Griffiths Juliet Browne Tim Martin IN ATTENDANCE: Jeni Marshall (Temporary Clerk) Six members of the public Hugo Mander of Owlpen Manor APOLOGIES David Sykes (Footpath Officer) Jim Dewey (Stroud District Councillor) 1/9/18 To receive apologies for absence Apologies were received as above 2/9/18 To receive any representations from members of the public Six members of the public requested to speak regarding the Owlpen Manor Planning application. It was agreed they would speak when the agenda item came up. 3/9/18 To receive any declarations of interest None received 4/9/18 To confirm the minutes of the last meeting of the Council The minutes of the previous meeting was approved subject to an amendment proposed by Councillor Martin. 5/9/18 To consider any issues arising from the previous meeting This item was covered by minute number 4/9/18 6/9/18 To receive any reports from County and District Councillors The Chairman read a report from Councillor Dewey covering proposed car park charges which have now been scrapped, information regarding the new Chief Executive at Stroud District Council, Kathy O’Leary, the withdrawal of the Negative Revenue Support Grant, Brexit and Gloucestershire Vision 2050. 7/9/18 To receive a report from the Footpaths Officer The Footpaths Officer sent his apologies. Councillor Martin once again reported a broken style which had been reported at the previous meeting but is still not fixed. -

4232 the London Gazette, 7 August, 1951

4232 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 7 AUGUST, 1951 Arkwright House, Parsonage Gardens, Deansgate, Sodbury—Alderley, Hawkesbury, Horton, Little Manchester. Sodbury, Badminton, Acton Turville, Tormarton, Every objection must state the grounds on which Marshfield, Cold Ashton; that part of Sodbury it is based. East of Commonplace Lane and East of road from A copy of every such objection must be sent to Coomb's End to Cotswold Lane;. those parts of the Town Clerk, Municipal Buildings, Library Street, Wick and Abson and Ooynton, East of the road Wigan, at the same time as it is sent to the Licensing from Upton Cheyney to Dryham; that part of Authority. Dryham and (Hinton (East of road from Upton Cheyney to iHinton and 'East of footpath from Dated this 26th day of July, 1951. Hinton to Dodington and that part of Doding- ALLAN ROYLE, Town Clerk. ton East of footpath from Hinton to Dodington. Warmley—That part of iBitton East of the road Municipal Buildings, from Upton Cheyney to Dryham. Library Street, Wigan. Stroud—Horsley, (Minchinhampton, iRodborough, (006) King's Stanley, Woodchester, Bisley with Lypiatt, Miserden, Cranham, Painswick, Pitch- combe, Whiteshill, Randwick, Chalford; that GLOUCESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL. part of Leonard Stanley East of the railway. Dursley—Nyonpsfield, Uley, Owlpen ; that part of TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT, 1947. Coaley South of the railway and that part of Wotton-under-Edge North-east of the road from TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (CONTROL OF Hillsley to Wotton-under-Edge and North-east of ADVERTISEMENTS) REGULATIONS, 1948-49, the road from Wotton-under-Edge to North County of Gloucester, Advertisements—Area of Nibley. -

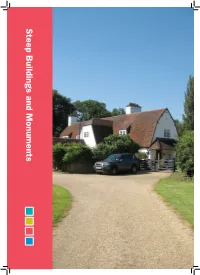

Steep Buildings and Monuments

Steep Buildings and Monuments Contents Introduction 1 Preface 3 Steep Parish Map 4 Ridge Common Lane 5 Lythe Lane 7 Dunhill and Dunhurst 7 Stoner Hill 9 Church Road 12 Mill Lane 25 Ashford Lane 28 Steep Hill and Harrow Lane 34 Steep Marsh, Bowers Common and London Road, Sheet 39 Bedales 42 The Hangers 47 Architects A - Z 48 The following reports also form part of the work of the Steep Parish Plan Steering Group and are available in separate documents, either accessible through the Steep Parish Plan website www.steepparishplan.org.uk or from the Steep Parish Clerk Steep Parish Plan 2012 Steep Settlements Character Assessment Steep Local Landscape Character Assessment October 2012 2 Introduction Steep is at the western edge of the Weald, within the Bedales grounds, the Memorial at the foot of the Hangers, with the Downs Library and Lupton Hall are outstanding and to the south. The earliest buildings were are Grade I listed. The influence of the Arts amongst a sporadic pattern of farmsteads and Crafts Movement can also be seen at at the foot of the Hangers’ scarp, which Ashford Chace, the War Memorial and Whiteman in the ‘Origins of Steep’ suggests Village Hall. were settled in early Saxon times. The The other influence that Bedales had on Hampshire Archaeology and Historic Build- Steep was through the parents of its pupils, ings Record confirms these suggestions. All who decided to live locally while their chil- Saints Church dates from 1125 and dren were educated at the School, Edward ‘Restalls’, a timber framed house on its east Thomas and his family being the prime ex- side is thought to be the oldest dwelling in ample. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

Kingswood Environmental Character Assessment 2014

Kingswood Environmental Character Assessment October 2014 Produced by the Kingswood VDS & NDP Working Group on behalf of the Community of Kingswood, Gloucestershire Contents Purpose of this Assessment ............................................................................................................................... 1 Location ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Landscape Assessment ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Setting & Vistas .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Land Use and Landscape Pattern .................................................................................................................. 5 Waterways ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Landscape Character Type ............................................................................................................................. 8 Colour ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 Geology ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Gloucestershire Parish Map

Gloucestershire Parish Map MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT 1 Charlton Kings CP Cheltenham 91 Sevenhampton CP Cotswold 181 Frocester CP Stroud 2 Leckhampton CP Cheltenham 92 Sezincote CP Cotswold 182 Ham and Stone CP Stroud 3 Prestbury CP Cheltenham 93 Sherborne CP Cotswold 183 Hamfallow CP Stroud 4 Swindon CP Cheltenham 94 Shipton CP Cotswold 184 Hardwicke CP Stroud 5 Up Hatherley CP Cheltenham 95 Shipton Moyne CP Cotswold 185 Harescombe CP Stroud 6 Adlestrop CP Cotswold 96 Siddington CP Cotswold 186 Haresfield CP Stroud 7 Aldsworth CP Cotswold 97 Somerford Keynes CP Cotswold 187 Hillesley and Tresham CP Stroud 112 75 8 Ampney Crucis CP Cotswold 98 South Cerney CP Cotswold 188 Hinton CP Stroud 9 Ampney St. Mary CP Cotswold 99 Southrop CP Cotswold 189 Horsley CP Stroud 10 Ampney St. Peter CP Cotswold 100 Stow-on-the-Wold CP Cotswold 190 King's Stanley CP Stroud 13 11 Andoversford CP Cotswold 101 Swell CP Cotswold 191 Kingswood CP Stroud 12 Ashley CP Cotswold 102 Syde CP Cotswold 192 Leonard Stanley CP Stroud 13 Aston Subedge CP Cotswold 103 Temple Guiting CP Cotswold 193 Longney and Epney CP Stroud 89 111 53 14 Avening CP Cotswold 104 Tetbury CP Cotswold 194 Minchinhampton CP Stroud 116 15 Bagendon CP Cotswold 105 Tetbury Upton CP Cotswold 195 Miserden CP Stroud 16 Barnsley CP Cotswold 106 Todenham CP Cotswold 196 Moreton Valence CP Stroud 17 Barrington CP Cotswold 107 Turkdean CP Cotswold 197 Nailsworth CP Stroud 31 18 Batsford CP Cotswold 108 Upper Rissington CP Cotswold 198 North Nibley CP Stroud 19 Baunton -

South West West

SouthSouth West West Berwick-upon-Tweed Lindisfarne Castle Giant’s Causeway Carrick-a-Rede Cragside Downhill Coleraine Demesne and Hezlett House Morpeth Wallington LONDONDERRY Blyth Seaton Delaval Hall Whitley Bay Tynemouth Newcastle Upon Tyne M2 Souter Lighthouse Jarrow and The Leas Ballymena Cherryburn Gateshead Gray’s Printing Larne Gibside Sunderland Press Carlisle Consett Washington Old Hall Houghton le Spring M22 Patterson’s M6 Springhill Spade Mill Carrickfergus Durham M2 Newtownabbey Brandon Peterlee Wellbrook Cookstown Bangor Beetling Mill Wordsworth House Spennymoor Divis and the A1(M) Hartlepool BELFAST Black Mountain Newtownards Workington Bishop Auckland Mount Aira Force Appleby-in- Redcar and Ullswater Westmorland Stewart Stockton- Middlesbrough M1 Whitehaven on-Tees The Argory Strangford Ormesby Hall Craigavon Lough Darlington Ardress House Rowallane Sticklebarn and Whitby Castle Portadown Garden The Langdales Coole Castle Armagh Ward Wray Castle Florence Court Beatrix Potter Gallery M6 and Hawkshead Murlough Northallerton Crom Steam Yacht Gondola Hill Top Kendal Hawes Rievaulx Scarborough Sizergh Terrace Newry Nunnington Hall Ulverston Ripon Barrow-in-Furness Bridlington Fountains Abbey A1(M) Morecambe Lancaster Knaresborough Beningbrough Hall M6 Harrogate York Skipton Treasurer’s House Fleetwood Ilkley Middlethorpe Hall Keighley Yeadon Tadcaster Clitheroe Colne Beverley East Riddlesden Hall Shipley Blackpool Gawthorpe Hall Nelson Leeds Garforth M55 Selby Preston Burnley M621 Kingston Upon Hull M65 Accrington Bradford M62 -

Regulatory Board Commons and Rights of Way Panel 18 September 2003 Agenda Item: 6 Application for a Modification Order for an A

REGULATORY BOARD COMMONS AND RIGHTS OF WAY PANEL 18 SEPTEMBER 2003 AGENDA ITEM: 6 APPLICATION FOR A MODIFICATION ORDER FOR AN ADDITIONAL LENGTH OF BRIDLEWAY BETWEEN BRIMSCOOMBE WOOD AND SCRUBBETT'S LANE, SOUTH OF CONYGRE WOOD, NEWINGTON BAGPATH PARISHES OF KINGSCOTE AND OZLEWORTH JOINT REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: ENVIRONMENT AND THE HEAD OF LEGAL AND DEMOCRATIC SERVICES 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT To consider the following application: Nature of Application: Additional bridleway Parishes: Kingscote and Ozleworth Name of Applicants: Ben Harford and John Huntley Date of Application: 7 May 2002 2. RECOMMENDATION That a Modification Order be made to add the length of claimed bridleway to the Definitive Map. 3. RESOURCE IMPLICATIONS Average staff cost in taking an application to the Panel- £2,000. Cost of advertising Order in the local press, which has to be done twice, varies between £75 - £300 per notice. In addition, the County Council is responsible for meeting the costs of any Public Inquiry associated with the application. If the application were successful, the path would become maintainable at the public expense. 4. SUSTAINABILITY IMPLICATIONS No sustainability implications have been identified. 5. STATUTORY AUTHORITY Section 53 of the Wildlife. and Countryside Act 1981 imposes a duty on the County Council, as surveying authority, to keep the Definitive Map and Statement under continuous review and to modify it in consequence of the occurrence of an `event' specified in sub section [3]. Any person may make an application to the authority for a Definitive Map Modification Order on the occurrence of an `event' under section 53 [3] [b] or [c].